|

|

Initials

and Borders (2) |

|

Some

initials became more elaborate, and also emphasised their function as

a place marker to identify sections of text, with the development of historiated

initials. |

|

|

The

initial at the beginning of the heading in the last example (British Library,

Cotton Vespasian A1, f.31) is reportedly one of the earliest examples

of the type, from the early 8th century. By permission of the British

Library.

|

|

Particular

forms and images were associated with specific parts of the text of standardised

works like the Bible.

The decorative style changed with the fashions of the day. To designate

these as place markers is possibly reducing their function to the ordinary

and banal, when in fact there was a spiritual dimension. The examples

below refer to the beginning of the Psalms,

those songs of praise found not only in their original source of the Bible,

but featured in all the works of church liturgy

and in the book

of hours for the laity. The extravagant BEATUS marks not only the page of a book but a spiritual space. Similarly the

significant In principio erat verbum ... passage at the beginning of St John's gospel

was often singled out for special treatment; a definingly spiritual passage

embedded in the narrative of Christ's life. |

|

|

|

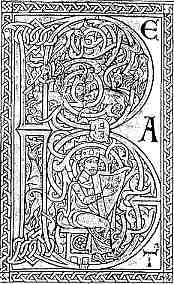

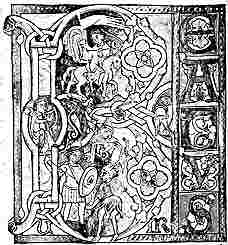

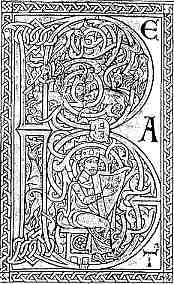

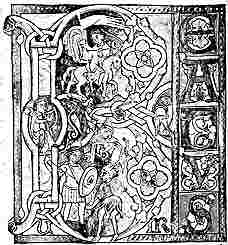

Two

examples of the initial B of the word

Beatus which begins Psalm i, both from 12th century manuscripts.

That on the left is from the Melissande Psalter (British Library, Egerton

MS 1139, f.23) and features David playing his harp among twining foliate

ornament and animals, including a lion eating the foliage. That on the

right is from a Bible (Paris Bibliothèque St Geneviève,

MS8-10, vol.ii, f.194) and includes the foliage and an image of David

with his harp along with other scenes. Yes, they would look much more

impressive in colour. |

|

A

historiated initial illustrates the text in some way, possibly providing not

only a place marker but a mnemonic device to jog the memory. In the example at left the

letter C begins the phrase cantate

domino, which is what the little group of clerics are doing, singing

to the Lord |

|

From the Luttrell Psalter (now in the British Library). |

|

While

initials bore a relationship to the text, borders seem to most often contain

purely decorative elements or those whose significance is related to the

art style and psyche of the era rather than the content of the page. During

the 14th century borders broke out in an extravaganza of mad imagery,

with fantastic creatures, little genre scenes and crazy whimsical anomalies.

Solemn and prestigious works were not immune from this phenomenon. In

fact, they were the most likely subjects for it. It seems to go along

with similarly bizarre representations in church art, where what seem

like inappropriate things appear in holy places. I shall not even attempt

anything so fanciful as to relate it to the famines and plagues of the

era and a desperate attempt to mock gently at God in order to get his

attention. However, if you find a monkey examining a urine flask or a

creature with three heads and no legs standing upside down, you have hit

the era from around 1330. |

|

A

furry footed fiddler makes the bow hair fly in a margin of the Luttrell

Psalter (now in the British Library). |

|

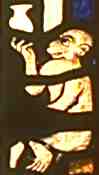

A

monkey examines a urine flask in a 14th century nave window in York Minster. |

|

By

the 15th century there was a return to floral and foliate ornament, only

with a more naturalistic representation than the twining jungle vines

of the 12th century. That is to say, there was plenty of curling and less

interlacing, but recognisable species of flowers, fruit and sometimes

animals and birds were sprinkled among them. You can put it down to Italian

influences on the more accurate representation of reality, to a growing

interest in the natural world, to a more benign social and natural environment

which requires fewer monsters to scare the demons away, to the commodification

of culture and the moving of prestige goods into the comfort zone. Or

you can just say it's very pretty. |

|

Floral

and foliate border on a leaf from a late 15th century book of hours, by permission

of the University of Tasmania Library. |

|

continued  |

previous

page previous

page |

Decoration Decoration |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|