a portrait of the French soldier as seen by a British writer

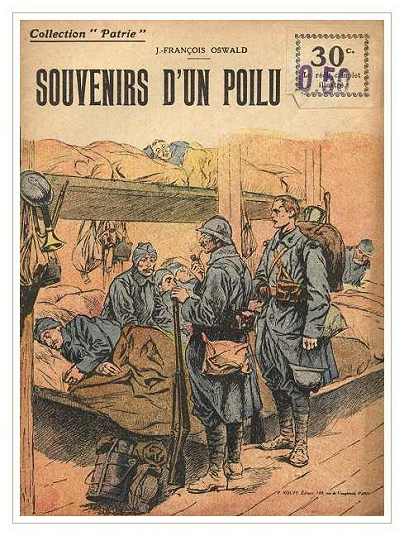

French soldiers from a print in 'Panorama de la Guerre'

The Spirit of France

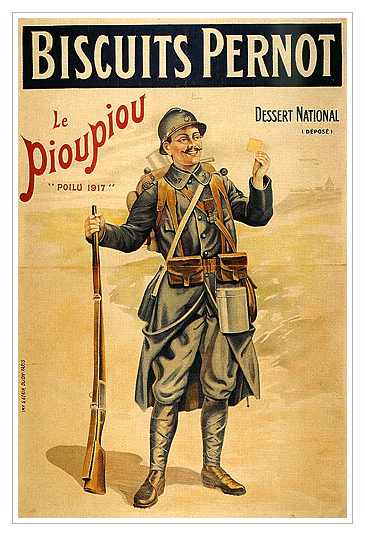

To British military standards of kit and uniform, "Le Piou-piou," as the French "Tommy Atkins " is nick-named, is a tramp. In the face of our own serviceable khaki, his clothes are fantastic and odd; his blue overcoat, buttoned behind at the knees, is too heavy; his trousers, even when they are not the balloons of the Algerian regiments, are too baggy; his heavy cuirass is cumbersome; and the whole of him is usually slouchy and rather dirty. Moreover, le piou-piou does not seem to care. His clothes are curious, but he does not mind; they do not fit him, and he seems to accentuate the misfit by deliberate casualness.

His Odd Appearance

In appearance, also, he is a little odd to our standards. He is built on too many different and conflicting scales, and nobody has troubled to sort him out into different grades of height. Some of the men are tall and strong, others are short to a degree, and some are weedy; but whatever the height or physique, all are lumped together into that odd jumble of men that makes a French regiment. Again, in all this incongruity, le piou-piou does not seem to mind. The tiny man marches unconcernedly by the tall one; both crack their witty jokes, refrain from shaving, are careless about washing, and are indifferent to the scrubbiness of their uniforms. And the reason that le piou-piou does not mind about these things is because he knows they do not matter. Battles are not won by clothes, but by the man beneath them.

Suspicious of Parade

Indeed, not only is le piou-piou indifferent to outward effect, but the whole military idea of France aims at scrapping all external show in favour of military efficiency. Mr. Hilaire Belloc, himself a one time private in the French artillery, explains why this is.

"There are," he says, "features which flow from the defeat of forty-four years ago, and the chief of these, perhaps, is a suspicion of everything that savours of parade, and a concentration upon everything that may be, or is believed to be, of immediate practical use in war. Everything was scrapped, or nearly everything, which could be regarded as merely of moral effect, or as merely traditional. If the uniform was kept for so long, it was because there was so strong a difference of opinion upon the advantage of neutral colours; and perhaps this campaign will prove those to have been right who despised the spirit behind protective colouring and, at the same time, denied its practical value. The elaborate presenting of arms, the ritual of changing guard (save in its barest elements), the idea of corps d'élte, exactitude in certain antiquated manneuvres, and twenty other things whose value must not be denied merely because they cannot be directly proved to be of material value in the field, went by the board. The result was the creation of a service from which not only the picturesque had nearly disappeared, but even those externals which, for the civilian mind, are specially characteristic of soldiers."

The Man Beneath the Slouch

The man beneath the slouchy French uniform is a fine fellow. He is generally hard, and he is usually wiry, and those who have judged by appearances only have had many rude shocks when they have seen the way the French private stands the grinding test of active service. In spite of his slouch and his irregular ranks, le piou-piou is one of the best marching units in the whole of Europe, and in the severe trials of campaigning can put up with an amount of hardship that would send many a crack regiment of other countries to hospital in a very short time. Through it all, too, he preserves with vivacity and smiles his unquenchable spirit.

The Soul Within

It is the spirit within the French private that is making him so formidable in war. Le piou- piou is a gay, volatile, impressionable, patriotic, fiery, casual, electric creature, and the chemical action on the soul of all these emotions makes him a fighter of terrific élan. He suffers a little from the intensity of these qualities. He is apt to be soon depressed, he is likely to be dispirited too easily by reverses, he is sometimes inclined to be unstable at critical moments. On the other hand, he gains from them more than he loses. Thanks to them, he is the most terrible fighter in the world to meet in an open attack. Give him the word to go, and not all the legions of Kaiserdom will stop him this side of victory or death. His flair with the bayonet is irresistible. At Charleroi, in the early days of the war, French infantry regiments swept clean with the bayonet that shattered village on six separate occasions. In the retreat towards Paris the Turcos are said to have charged over two miles under heavy fire in order to get at and slay the hated Germans. Indeed, at all times during the war the officers have had the greatest difficulty in holding their men, so eager were they to get to close quarters and use cold steel.

The Spur of the Women

This intense and eager spirit is in the very life-blood )f France. Young France has suckled it at the mother's breast, for it is nut of the strong souls of the women that it comes. One woman, a workgirl, donning a Zouave uniform, shouldered a rifle, fought battles, marched thirty miles a day with the troops, until she was wounded and found out. Another woman, a sister, sends to her fighting brother a letter ringing with that clarion note of courage that has made the history of France epic:

"Dear Edward, I have just heard that Charles and Lucien are dead and Eugene mortally wounded. Louis and Jean are also dead (all brothers). Rose has disappeared. Mother is crying, but says you are to go to avenge them. Jean had the Legion of Honour. You must have it now. Eight of us have been killed now, so do your duty. Think of your brothers and of grandfather in '70."

Sisters or mothers, the women are all imbued with this burning zeal for France. An old peasant woman, crouching by a graveside, looked up to tell her story. The grave was the grave of her crippled boy of fifteen. He had been seized by a German troop to act as a guide. He refused, and, when threatened with death, defied the officer, spat straight in his face and died. "But, monsieur," said the old mother, proud in her grief, "he was French, and although he was a cripple it was not denied him to serve his country."

Magnificent Patriotism

Magnificent spirit, magnificent patriotism Through the women, through the mothers and the wives and the sisters, the whole of France has been saturated with this indomitable essence of defiance and determination to win. Every man in France is a piou-piou at soul, from savant to road-sweeper, from generals to youths in their teens. Monsieur Anatole France the greatest writer of his land, writes at seventy years old to the Minister of War :

"MONSIEUR LE MINISTRE. - Many worthy people consider my style no good in war- time. As they are perhaps right, I have stopped writing, and am thus without a job. I am no longer very young, but my health is good. General Castelnau refuses to leave his post in battle, though his son was wounded and dying, and even when the young man was dead he refused to shed tears. Embracing the dead body, he cried : "My son, you have had the finest death that one could wish. I swear that our armies shall avenge you by avenging all the families of France."

The Very Children have the Spirit

The children, too, have the spirit. A little farm lad, Gustave Chatain, aged fifteen, went through several battles in France. His youth could not conquer his determination to fight for the Fatherland. "I'm big and strong for my age," he said, "and I wanted to fight the 'Boches', so one morning I sneaked off toward Senlis, where I heard the sound of fighting. On the way I came upon some Chasseurs Alpins and followed them, offering to do their errands for them. Then I asked them for a rifle. At first they laughed, but finally they gave me one. Then the captain saw: me and sent me away. He said I was only a child. I walked on again, and came up with another company, who let me march with them, when I promised to be good and keep out of sight. At last we saw the Boches, and fighting began. I picked up the first rifle I saw and fired away. Nobody paid any attention to me, and I advanced till I found myself quite alone. I had lost my company. Then I came upon another regiment of the line, whose soldiers allowed me to slip into their ranks. That brought us to the battle of the Marne. You can imagine that I enjoyed myself. When things warmed up I used to advance with the others."

The Boy in a Bayonet Charge

This amazing child, who should have been in the schoolroom, has been through events that test strong men.

"I've been in a bayonet charge. In the charges we hold a bundle of hay in front of us. It is a good way of getting near the Boches. I've been in their trenches, too. They sham dead. It is one of their tricks. I used to give them a little kick to see whether they were shamming," and he wound up his adventures by capturing seven Germans. "I had been with the advance posts for two days when it occurred to me to get up into a loft, to see where the Boches were. I found the door of the house closed, and looked through a crack in it. Inside I saw German haversacks and cartridges on the floor. I got a piece of wood and broke in the door. I had first loaded my rifle and fixed my bayonet. When I got inside there was nobody on the ground floor. I went up into the loft, and found seven Boches sleeping on the floor. They woke up when I came in, and when they saw my fixed bayonet they did not even attempt to resist, but held up their hands. 'Come down,' said I, and they came down, quite pleased to have a chance of surrendering. I handed them over to my regiment."

"Smile and Fight"

Such is the splendid spirit of le piou-piou, which is the spirit of France today It sustains him unconquerable on the bloody fields of War It is the determination to do all things for his country and to do it with fine, singing, valorous men. “We will defend it, and our watchword will be ‘Smile,' '' cried Colonel Doury, of the ;;th Infantry when called upon to hold, against enormous odds, a bridge across a river.

“He was killed at his post soon afterwards by a shell splinter," the despatch ends. But his soul was not killed. "Smile and fight," that is the soul of France, and it still lives.

W. D. N.

drawing by George Scott from the French newsmagazine 'l'Illustration'

*In the early days of the war, French soldiers were still nicknamed 'piou-pious', the more familiar term of 'poilu' not yet being in vogue. Most probably the longer lived Belgian slang word for soldier - piot - is derived from 'piou-piou'.

from 'Piou-piou' to 'Poilu'

For what it is worth, here is a possible explanation:

_______________________________________

The Little Piou-piou

The French "Tommy"

- Oh, some of us lolled in the chateau,

- And some of us slinked in the slum;

- But now we are here with a song and a cheer

- To serve at the sign of the drum.

- They put us in trousers of scarlet,

- In big sloppy ulsters of blue;

- In boots that are flat, a box of a hat,

- And they call us the little piou-piou,

- Piou-piou,

- The laughing and quaffing piou-piou,

- The swinging and singing piou-piou;

- And so with a rattle we march to the battle,

- The weary but cheery piou-piou.

- Encore un petit verre de vin,

- Pour nous mettre en route;

- Encore un petit verre de vin

- Pour nous mettre en train.

- They drive us head-on for the slaughter;

- We haven't got much of a chance;

- The issue looks bad, but we're awfully glad

- To battle and die for La France.

- For some must be killed, that is certain;

- There's only one's duty to do;

- So we leap to the fray in the glorious way

- They expect of the little piou-piou.

- En avant!

- The way of the gallant piou-piou,

- The dashing and smashing piou-piou;

- The way grim and gory that leads us to glory

- Is the way of the little piou-piou.

- Allons, enfants de la Patrie,

- Le jour de gloire est arrivé.

- To-day you would scarce recognise us,

- Such veterans war-wise are we;

- So grimy and hard, so calloused and scarred,

- So "crummy", yet gay as can be.

- We've finished with trousers of scarlet,

- They're given us breeches of blue,

- With a helmet instead of a cap on our head,

- Yet still we're the little piou-piou.

- Nous les aurons!

- The jesting, unresting piou-piou;

- The cheering, unfearing piou-piou;

- The keep-your-head-level and fight-like-the-devil;

- The dying, defying piou-piou.

- A la bayonette! Jusqu'a la mort!

- Sonnez la charge, clairons!

- by Robert Service

- from "Rhymes of a Red Cross Man'

- see a website with poetry by Robert Service : 'Rhymes of a Red Cross Man'

a French song dedicated to the 'Poilu'