from 'The Great War' Chapter XLII edited by H.W.Wilson 1914

THE BOMBARDMENT AND FALL OF ANTWERP

*see a collection of full pages from 'The Great War'

The Cruel Shelling of Malines Cathedral on the Sabbath - Beaten by Soldiers, Germans Slaughter Women Coming from Prayers - Battles for the Path to the Sea - Decisive Belgian Victories Round Termonde - German General Makes a Mistake that Saves the French Coast - Desperate Position of Belgian Army in Antwerp - No Guns with the Range of the Austrian and German Howitzers - Fall of Antwerp Forts Certain - Belgians Undertake an Impossible Task to Help their Allies - Terrible End of the Garrison of Fort Waelhem - Ten Blackened, Burnt, Groping Figures Emerge from the Ruined Fort after Fort Falling under a Rain of 12 in. Shells - The Raging, Murderous Struggle for the Nethe - Mr. Winston Churchill Arrives with the Naval Division - Scheme of Large Operations for the Relief of Antwerp - Sir Henry Rawlinson and the 7th Division Forced Back - The Bridge of Death at the Nethe - Shells begin to Fall in the City -The Dreadful, Tragic Flight of Half a Million Townspeople - Defending Forces Withdrawn - How the German Commander was Tricked - Empty and Costly Triumph of the Outplayed Teutons - Only the Husk of a City Won by Them.

The fall of Antwerp was the most tragic episode in the greatest of wars. For two months the heroic little Belgian Army had stood against the mightiest military power in the world, and towards the close of September it was expected that Antwerp would be relieved by the far-reaching operations of the Franco- British armies gathering about Lille.

But the enemy was too quick in his double attack against the Allies. By a supreme effort, General von Falkenhayn collected every available soldier, and flung his last reserves against the extending trench line. Then, with some 125,000 young fresh troops of the first-line armies, and the siege-artillery collected for Paris, he began the attack on Antwerp.

Characteristically cruel was the manner in which the Germans opened their campaign against the Belgian Army in its last stronghold. At 9.30 o'clock on the morning of Sunday, September 27th, the townspeople of Malines came out of their beautiful old cathedral of St. Rombold, and stood talking in groups in the large, ancient market-place, surrounded by picturesque gabled houses of the sixteenth century. In front of them rose the old Cloth Hall, built in the days when Mechlin, as the Flemings call their town, was the Manchester of Northern Europe. Many of the older women who came out of the cathedral- pale-faced, black-clad, working-class women-were the famous Mechlin lace-makers, esteemed throughout the world for the delicacy and beauty of their work. As they gathered together for a gossip, there was a distant roar, a loud shriek, and overhead a dreadful explosion, as the first shell struck the cathedral.

The gentle German, with the assistance of the gentile Austrian, was resuming his work of terrorizing the harmless and peaceful non-combatant population of Belgium. All day the great shells rained on the stricken town, some fifty falling every hour. The glorious thirteenth-century cathedral, with its richly- carved choir and its magnificent tower, with the finest chimes in the world, was almost completely destroyed. The railway-station and barracks were set on fire, and the magnificent old buildings, erected in the days when Mechlin was the capital of both Holland and Belgium, were wrecked and burnt. Ten of the townspeople were killed, and very many more wounded. Most of them fled northward to Antwerp, the two outermost Antwerp forts, Wavre and Waelhem, being only two miles north of Malines.

No military purpose was served by this sudden destruction of an open town. The Germans, moreover, offended against the laws of civilized warfare by giving no notice of the intended bombardment. The fact was that the wrecking of Malines and its cathedral, like the wrecking of Rheims Cathedral, was a deed of devilish spite. On the previous day, Saturday, the German commander of the attacking forces, General von Beseler, had attempted to cut the communications of the Belgian Army in Antwerp by a movement westward on Termonde. There was then a gap of only forty miles between the left wing of the German forces and the Dutch frontier. If Beseler could have closed this gap by a further advance northward to the town of St. Nicolaes, on the railway line from Antwerp to Ghent and Ostend, he would have completely encircled the Belgian Army. He would also have made it impossible for any reinforcement to reach Antwerp.

His attempt at an enveloping movement was, however, defeated by a sortie of the defenders. The. front of the Germans stretched for twenty miles, almost to Ghent, with only a small Belgian advance force holding the bridge of Termonde across the Scheldt against them.

The enemy brought his field-howitzers along the Flemish plain, and pressed the Belgians very hard. At two important points, the village of Audegem, about two miles south-west of Termonde, and the village of Lebbeke, a little distance south west of the same town, two parties of seven hundred Belgian troops held the Germans off all the morning. When a third of the little Belgian forces had fallen, they were reinforced, and, driving at the enemy, they forced him back down the roads towards Alost and Brussels.

Terribly did the Germans suffer. For the Belgians gave them no rest, but continued the pursuit on Saturday night and Sunday morning, and drove them out of Alost, which town they had occupied for three weeks. Some thousands of Germans were killed and wounded. It was out of revenge for this great and disastrous defeat-a defeat with extraordinary consequences for Germany - that the decivilized neo- barbarians bombarded the cathedral city of Malines on Sunday morning.

It is scarcely too much to say that after the Battle of Termonde, General von Beseler lost his head. It would be rating his mistake too highly to say that it deprived the Germans of all chance of victory in the western theatre of war. For even if the mistake had not been committed, it is doubtful whether the German flanking movement between Lille and Calais would have succeeded. But Beseler's lack of initiative, tenacity, and genius for war, certainly resulted at Termonde in an apparently local disaster with extraordinarily wide-spread effects. No study of strategy is necessary to judge his error. Anybody with ordinary common-sense can see that he should have concentrated all available forces against the Belgians at Termonde - a hundred thousand men, if necessary - in order to cut their communications with the coast, and to drive them back into Antwerp. This should have been done before siege operations were started, and the larger part of the more mobile artillery should have been employed in this absolutely vital operation.

But little things have large effects on little minds. It was quite a little thing that upset the balance of the German general's intellect -a mere rumor. Somebody on the Belgian Military Staff was artful enough to spread the report that a large British force was momentarily expected to land at Ostend, and speed up by railway against the western wing of the German forces. On Sunday morning the perturbed German commander sent out Uhlan patrols, who spent all their time questioning the Flemish peasants as to the whereabouts of the new British army. Perhaps our Marine force at Ostend had moved about the country a little; perhaps the Belgian villagers thought that even an imaginary British column would rid them for a time of the presence of the hated invader. However this may be, some of the reconnoitering Uhlans returned to headquarters with sufficient vague information at second-hand to determine their commander to retire eastward and concentrate between Brussels and Louvain.

By this means the Belgian Army was saved, even when Antwerp fell some eight days afterwards. For all through the bombardment the Belgian line of communication with the seacoast was kept open. On some days the Germans massed thirty thousand men against it, but these strokes came too late. General de Guise, commanding at Antwerp, always managed to bring up sufficient troops to hold the railway to the coast, while his opponent, General von Beseler, was stupidly concentrating mainly against the weak and indefensible rings of Antwerp forts.

Right from the beginning there was no hope for Antwerp. The Belgian Army's desperate defense of their last strong-bold was but a gesture of heroism by a little nation dying in immortal fame and in the hope of a glorious resurrection.

The old semi-circle of armored forts had become worse than useless. With the surprising development in power of modern siege-artillery, Antwerp had ceased to exist as a fortress. Its great structures of armored concrete, with their cupolas of thick hardened steel were merely death-traps. A line of earthworks in an open field would have formed a far safer defensive position.

The proper method of strategy would have been for the weary and outworn Belgian Army to have retreated by rail towards Dunkirk. In so doing, however, it would have released 125,000 young athletic German soldiers for the attack upon the French line between Lille and Calais. That line would then have been broken. It would have been broken at least a week before the British army moved up from the Aisne valley to strengthen it. Thus the Belgians had once more to stand in the breach, and protect France against an overwhelming surprise attack. They had to hold at least three, and possibly four, first- rate German army corps round Antwerp for as long a time as was humanly possible, in order to prevent this force from being thrown against the feeble Northern French line, and sweeping down towards Havre and Paris again.

Every Belgian officer knew the hopelessness of the task.

German siege-artillery was a terrific power. Manonvilliers, a very strong, isolated French fort, had been shattered in a week. The last of the Liege forts had fallen after a bombardment of seven days, while those of Namur barely held out fifty hours. Even the strong modern defenses of Maubeuge, with a large garrison, bad been completely battered into shapeless ruin in eight days. The forts of Antwerp, designed by General Brialmont thirty years before, and gunned with artillery of small caliber and short range, were doomed. Their fall was not a question of days, but a matter of hours. They had only 6 in. guns.

Yet, knowing all this, the heroes of Belgium stuck to their job. Their courage was of that flaming, passionate sort that puts things again, and yet again, to mortal hazard. Antwerp, their beloved Antwerp, with its picturesque of the Belgians streets, its historic and romantic memories, its treasures of native art, its multitudes of free and independent townsmen - Antwerp, with its far-stretched lines of forts, built in the old days to shelter the entire Army - could not be tamely surrendered. Belgium would not play for safety. Her forces were worn out by countless battles and skirmishes, and sadly diminished by a fighting resistance of two months against an overpowering host of invaders. But the Belgian had ceased to calculate his chances of life. Cost what it might even the destruction of the entire military forces of the nation - Antwerp should not be surrendered without a struggle.

It was the most sublime spectacle in the annals of warfare. Antwerp, with its old and useless forts, looked like being the burial-place of the Belgian troops. Yet, standing by the grave of their power as an independent people, the Belgians jumped in, rifle in hand, and used the grave as a fighting-trench. It was six weeks since they had withdrawn from the field into their last stronghold. Had they at once, on August 17th, the date of their retirement, devoted themselves entirely to reorganizing the defenses of the fortress, they could have made it impregnable. They could have taken the guns out of the forts and used them as mobile batteries, and have obtained 12 in. weapons from England, for use on moving platforms running on a railway track. By this means they could have made Antwerp as difficult to reduce as Przemysl or Verdun. This, however, was not done. For the Belgian troops were occupied in making continual sallies again4 the enemy's forces, and threatening his lines of communication, in order to relieve the pressure on the French and British troops in the south. Never in history has there been such self-sacrificing conduct towards allies as the Belgians continually displayed. Their Christian courage far surpasses that of the Spartans and Athenians. Not till the Belgian showed what was in him did man know what the spirit of international fraternity could achieve. The Belgians saved the modern world, the modern spirit of humanity, the modern faith in the plighted word of States. Strange as it may sound, the deaths and wounds of Belgian soldiers, the sufferings redeemed the crimes international of the Germans. For they erased the effect of German international treachery from the mind of the world. So long as countries put faith in treaties between nation and nation, so long will the example of Belgium have a Christlike power upon man.

The attack on the Belgians' last lines of defense began on Monday, September 28th. The Austrian artillery detachment at Brussels brought forward their 12 in. siege-howitzers to concealed positions behind the Malines-Louvain railway embankment, far beyond the reach of the old 6 in. Krupp guns in the Antwerp forts. Having manufactured them, the Germans knew that these guns had an effective range of only about five miles. The Austrian siege-howitzers, on the other hand, threw their terrible shells with mathematical exactitude to a distance of seven and a half miles, and with fair marksmanship to a distance of nine miles, They opened fire on Fort Waelhem and Fort Wavre Ste Catherine. All the day and all the night the shells continued to fall on and around the forts. With anything like equal artillery on both sides, this nocturnal bombardment would have been more disastrous to the Germans than to the defenders. For the flames of the attacking howitzers could clearly be seen in the darkness from the captive observation balloon employed by the Belgians. It would have been easy to have planted shell after shell among the besieging batteries, if only the Belgians had had ordnance of a proper range fixed on movable trucks behind their lines. As it was, the defenders were impotent to reply to the long-distance fire from the Skoda 12 in. batteries and the Krupp 11 in. batteries.

The time-fuse of one of the shells that were thrown in the Belgian lines, where it failed to explode is understood to have been set for 15,200 meters. This is about nine and a half miles, a larger distance than the Skoda howitzer is reckoned to cover. So it is possible that the Germans had even more powerful siege-artillery before Antwerp than is generally supposed. Something between a 12 in. howitzer and a 16 in. howitzer may in places have been employed. For the enemy was so anxious to reduce Antwerp with the utmost speed, and to release his army corps for operations between Lille and Dunkirk, that he massed every available machine of destruction against the Belgians.

The attackers, however, were so confident in their overpowering weight of metal that they were caught by a very simple trick. Early in the bombardment, one of the forts in the outer ring of defenses quickly exploded and burst into flame. A brigade of German infantry, entrenched just beyond the range of the Belgian guns, rose and charged across the fields to capture the ruined stronghold, and hold the gap in the fortressed line against the defending troops.

But when they reached the fort, guns, machine-guns, rifles, and live electric-wire entanglements caught them in a trap. The flame had been produced by pouring petrol on some lighted straw brought into the fort for the purpose. One-third of a German brigade fell around the slopes; the rest fled, with shrapnel and Maxim fire sweeping them as they ran. Scarcely a fortnight before, the commander of the French fort at Troyon had lured on and half-annihilated a large body of German infantry by the same device of apparently setting his fort on fire. If the Germans had not so despised their enemies, they would not have been caught twice within a fortnight by the same easy trick.

The Belgians also succeeded in bringing oft the most primitive of all artillery maneuvers - the dead-dog dodge. They slackened their fire and encouraged the Germans to grow venturesome, and to push forward their howitzer batteries belonging to the field-artillery. Between tire Belgian forts were lines of trenches held by the Belgian Army, with light field-artillery operating behind the troops. For some time the German gunners seemed to have certain of these trenches at their mercy. They pushed forward three batteries to complete the work of annihilation. But a semicircle of thunder and flame suddenly opened before them. Every dead Belgian gun came to life again. Two of the German batteries were destroyed, and tire other managed to harness up its guns and to get away.

These were the only successes of the outranged and overpowered forts. The five hundred men garrisoning Fort Waelhem were the first to suffer, as their comrades at Liege and Namur had suffered. They took part in the sortie on Malines, and then retreated to the fort. On Monday the first German shells fell short, and the garrison began to hope they would he able to resist. But soon one of the 12 in. Austrian howitzers landed a shell on a cupola and smashed it All Monday night, shell and shrapnel rained down on the buildings of the fort, giving the garrison neither rest nor respite. The Belgian guns salvoed in reply, but could not reach the enemy.

By Tuesday morning the situation was critical. The shells were still falling with an infernal tumult on the armor of the cupolas, and just at noon another of the curved, shielding roofs of hardened steel was put out of action At twenty minutes past twelve the bombardment increased in fury. Three large projectiles struck the garrison building and completely destroyed it, twisting the iron stairs, smashing the vault, blowing up the walls to the foundation, and setting the wreckage on fire. The troops then sheltered in the underground passage, waiting for the hurricane of high-explosive shells to slacken and enable them to return to their guns.

It was in the crowded subterranean shelter that the great catastrophe occurred. A shell dropped in the ammunition magazine, to the left of the underground gallery, and the flame and fume of the terrible explosion of the magazine swept through the thronged passage. Out of more than a hundred men only ten escaped - ten blackened, burnt, blinded, tortured figures, crawling in the darkness over the charred bodies of their comrades. And while they crept out into the daylight towards the postern, the shrapnel continued to fall around them, and shell after shell ground the shattered concrete to powder, gave the battered armor-plate another wrench, and the overturned guns another useless hammering.

It was a vision of hell such as the imagination of Dante never attained. And it was not a vision, but the work of Christians fighting against Christians - the work of a great empire organized for scientific research and for the advancement of human control over the forces of Nature. Practically everything on the scene was German. The guns and the armor-plate of the fort had been constructed by Krupp, and it was he and his associate in the commerce of warfare - Skoda of Pilsen - who manufactured the howitzers and shells by which the fort was destroyed. Frau Krupp and her father had made hundreds of thousands of pounds out of the Belgians, and then obtained another large fortune out of the German people for newer and larger machinery of destruction to wreck the earlier examples of Krupp manufacture. It is said, moreover, that the Krupp guns built for use in Antwerp were specially constructed to wear badly when put to lengthy use. Oh, deep and far-seeing were the plans which Germany made for the war that was yet vainly designed to end in her conquering the world

Behind Fort Walhaem were the principal waterworks of Antwerp, and by bombarding the reservoir with 12 in, shells the Germans burst the banks on Wednesday, September 30th. The flood of water drowned some of the Belgian trenches and certain of the defenders' field-guns were submerged, and only rescued with great labor. The inundation also hampered the defense by interfering with the carrying of supplies and ammunition to the neighboring section of the Belgian lines. In Antwerp itself the destruction of the water supply naturally had distressing results, and it terribly increased the danger of a conflagration, and of the rise and spread of an epidemic. In the meantime, all the chief forts in the southern sector of the defenses went the way of Fort Waelhem. Wavre Ste. Catherine was the first to fall; then, after three days of continuous bombardment, Lierre and Koningshoyckt were silenced.

The village of Lierre was set fire, and the dense column of smoke that poured up from it in the windless autumn air was visible from a great distance.

With the fall of the south-eastern outer forts on Thursday, October 1st, the defense of Antwerp became impossible. For there was a gap of over ten miles in the circuit of fortifications, through which the enemy could pour his troops, while watering the path in front of them with shell and shrapnel. Moreover, the destruction of the principal Belgian forts allowed the Germans to move their heavy siege artillery northward for another two miles, and thus to get within bombarding range of the city. The small tidal river, the Nethe, flowing behind the southern ruined forts into the Scheldt, was the only remaining defense of the Belgians. For the picturesque ancient ramparts of the city were, of course, useless against modern siege-howitzers, and the line of inner forts, placed about two miles outside the city of Antwerp, were half a century old, and equipped only with 4 in. guns. They were still useful against infantry attacks, hut the ordinary field artillery of the modern army could have demolished them in a few hours. It was the outer recent forts, designed by General Brialmont in 1879, and completed in November, 1913, that guarded Antwerp. When a large sector of these defenses was destroyed, only the River Nethe and the entrenched infantry behind the river offered any real obstacle to the onset of the German forces. And this last obstacle, in the circumstances, was an exceedingly slight one. For by massing the fire of both their siege-artillery and their field-artillery on the shallow, hastily-made, and open earthworks by the river, the Germans subjected the Belgian troops to such a tempest of vast, high-explosive shells and heavy, wide- spreading shrapnel shots as mortal men had never known.

What our troops suffered by the Aisne flats was nothing to what the Belgians suffered in the flooded expanses by Nethe River. All the machinery intended for the destruction of Paris was concentrated on some eight to ten miles of their trenches, with the light field-artillery of several army corps joining in the screaming, roaring, nerve-racking work. Even with this the Germans did not think they had sufficient advantages over the small Belgian Army. They desired to use their overpowering long-ranged ordnance with scientific exactitude.

So several German men and women who had lived for years in Antwerp, and had enjoyed the friendship of the heroic Flemings, and had, therefore, been exempted from banishment from the beleaguered city, now came forward to direct the fire of the German batteries. Sometimes as nurses or Red Cross helpers, sometimes as interested and friendly spectators of the struggle, they approached the trenches, studied the positions, and communicated the knowledge thus obtained to the attacking gunners. When the great peace comes, other peoples may be moved by the craven and hysterical signs of repentance that the ordinary German will show in order to renew intercourse with civilized countries. But it is doubtful if the Belgian will be moved. He knows the German now, and has paid a very heavy price for his knowledge. He will not forget. For generation after generation he will not forget.

The Germans succeeded in crossing the How the Germans Nethe. A dozen times their engineers crossed the River Nethe advanced under cover of artillery fire, and tried to fling pontoons across the stream. The Belgians at first shot the engineers. Then, as they themselves were suffering heavily from the terrific bombardment, they adopted a more subtle means of defense. They let the pontoon bridges be erected, and waited until some battalions had partly crossed the river and were crowding the floating bridges from the farther bank. Then they opened fire with their light field-guns and machine-guns and rifles, sweeping the packed pontoons and banks. This went on night and day, till the Germans gradually built up a strange kind of bridge. Their bodies choked the river, and, mingling with the wreck of their pontoons, the corpses dammed and bridged the stream. But before this occurred, the Belgian Government had decided to leave Antwerp.

Two steamers were chartered to sail for Ostend on Saturday, October 3rd, with the members of the Government and the staffs of the French and British Legations. But on Saturday morning the plan was suddenly changed. The Belgian Government resolved to stay on. Great Britain at last was sending help to the breached and overpowered stronghold of the Belgian Army. At one o'clock on Saturday afternoon a long gray motor - Mr. Winston Churchill's car, filled with British naval officers entered the city. In it was a youngish, sandy-haired man in the undress uniform of a Lord of the Admiralty. It was Mr. Winston Churchill, and with him came General Paris, commanding a Marine brigade and two naval brigades, with a detachment of naval gunners with two 9.2 in. weapons and a number of 6 in. guns.

“We're going to save the city," said the most bustling member of the British Cabinet. But he had come a week too late to do so, and the forces he had brought with him, consisting mainly of untrained naval reservists, were inadequate to retrieve the situation.

Many of our men went into the trenches as soon as they arrived on Saturday evening. For the Belgian troops were utterly worn out by their long and severe exertions, and badly needed a rest. Some of our men were raw recruits who did not know how to handle a rifle, but they at least showed their native pluck by sticking in the trenches under the heavy bombardment. In all, they did not amount to more than eight thousand men, with two guns mounted on an armored train, and four 6 in. weapons that operated in the inner ring of forts, behind Lierre. It was intended that they should only act as a defending advance guard, and the 7th Division and 3rd Cavalry Division of the British Expeditionary Force, numbering some 18 000 bayonets and sabers, under General Sir Henry Rawlinson, was marching up to Ostend to reinforce them. At the same time, large French, British, and Indian cavalry bodies were operating eastward of Lille, with a view to clearing the way for a northward extension of the Franco-British front. It was the effect of all these combined operations which Mr. Churchill had in mind when he said that Antwerp would be saved.

But General von Beseler had made one mistake, and did not mean to make another. The tremendous advantage he had won on the southern sector was plain even to his mind, and he drove home the attack with sufficient determination to cover the lack of real generalship. All through the night of October 3rd he launched his infantry in massed formation across the Nethe by the shapeless ruins of Waelhem fort. The slaughter was terrible, but the German non-commissioned officers held their men together, even when there were only half-companies left to attempt to storm the Belgian trenches. When Sunday morning broke, the attacks still continued, until the Germans got their bellyful of fighting, and drew away to the river back to cover, leaving thousands of dead and wounded on the bank, and hundreds drowned in the water.

On Sunday night our Marines bore the brunt of the attack. They held some of the foremost trenches along the Nethe, between Lierre and Waelhem. The trenches were shallow and roughly made, and being open gave little protection against shell fire. The long-ranged guns of the enemy swept them from distant positions in the south, which the feeble defending artillery could not reach. Our casualties from shrapnel fire were very heavy; even veteran troops might have been pardoned had they abandoned the attempt to defend so indefensible a line. But our boys, untrained lads, some of whom had scarcely worn their uniform for a fortnight, went into the fight as they arrived, anti bided their fate as steadily as the bearded skilled men who fought beside them. Mr. Winston Churchill asked no one to undergo anything he was not eager to face himself. He took a rifle and stayed in one of the trenches near Fort Waelhem, anti shot with the best of them.

One of Mr. Asquith's sons was among the young recruits who proved their manhood and the mettle of the among the youth of their nation, under most desperate circumstances, and gave the Germans a foretaste of what the fighting qualities of the new British army would be when, with proper training, they took the held a million strong.

The massed attacks of the Germans on October 4th were first beaten off by our Marines. Then on October 5th the volunteer naval reservists arrived from the coast, and went straight into action north of Lierre. As they tramped down the cobbled and tree-shaded highway, they sang the new light-hearted British fighting-song, “It's a long, long way to Tipperary," while London motor-buses from Piccadilly and Leicester Square rumbled behind them with supplies and ammunition. The townspeople went wild with joy at the sight of these thousands of bright-faced, strong-limbed sons of Britain. Their city, they felt sure, was to be saved at the last moment .But there were military men who noticed that many of these raw young troops were so badly equipped that they did not even carry pouches for the regulation 150 rounds of fire.

Some of their officers seemed to be as lacking in field experience as the men. Yet these raw troops, rushed into Antwerp on a hopeless task, placed in open trenches unsupported by effective artillery, and raked by a terrific shrapnel fire, held the enemy back for some days, and then retired in perfect order. Seldom, if ever, have we put worse troops into the field, and seldom, if ever, has our cause been upheld by braver men. On the Nethe they beat the compact multitudes of first-line German soldiers back from the river, and when dawn broke, with a rain of shrapnel lead, the British trenches were still held. At four a.m. on October 6th, however, the Germans made their terrible bridge of dead on the right of the British forces, and the Belgian troops there were compelled to retire. Consequently our right flank was exposed, and our men had also to withdraw quickly to prevent the enemy from taking them in the reverse.

With this, the defense of Antwerp over the River Nethe practically came to an end. For, as we have seen, the old inner line of forts was incapable of resisting modern siege-artillery. Our few 6 in. naval guns were almost as useless as the old-fashioned 4 in. guns of the fort. They could do absolutely nothing against the 11 and 12 in. howitzers possessed by the Germans and Austrians. Our 9.2 in. guns could not be mounted and got into position in time. Even in the German field-artillery there were heavy howitzers, with a longer range and a larger shell than the half a dozen guns that Mr. Winston Churchill sent to Antwerp.

Mr. Churchill had served as a cavalry subaltern: But he seemed to have lacked at Antwerp the large organizing ability necessary in a commander of modern armies. He ran his head against the wide and well-laid plan of the German Military Staff, possessing vast resources for siege operations. Nothing less than a score of mobile 9'2 in. naval guns, with a squadron of aeroplanes searching for the enemy's positions, together with a large number of field-mortars for raking advancing columns of hostile infantry, could have turned the Nethe defense into a tenable position. All that the Belgians wanted was heavy artillery support. Even then their city might have been very severely bombarded. For as the outer forts had fallen in the south, the Skoda howitzers could have been brought much nearer the Nethe.

But it must have been said in Air. Churchill's defense that the call for help from Antwerp probably came too late for any large measures of assistance to be undertaken. The situation round Lille was also critical, so that our War Office could not immediately spare any regular troops for fortress ditties. The naval reservists were the nearest force to the point of embarkation, and could thus be carried most quickly to the spot where the need for tern was urgent and bitter. The danger of the enemy winning to the coast and establishing submarine centers of operations at the new seaport of Bruges, or even at Ostend Harbor or Calais, was an Admiralty problem. Mr. Churchill tried to solve it.

Heavily as our naval reservists suffered in dead, wounded, and missing, they did not suffer in vain. By helping to prolong for nearly a week the resistance of Antwerp, they did much to defeat the main objective of the enemy. For the capture of Antwerp was only a secondary aim of General von Beseler. The principal objective of the German commander was the destruction or capture of the Belgian Army. In failing to achieve this, he was defeated in his chief purpose. Towards this defeat, our volunteer reservists, with their comrades of the Marine brigade, contributed in no small measure.

What they actually did, in staving off the German infantry attack, was of local importance. What they potentially did, by their mere presence, by their sunny, cheerful faces, when the spirit of the heroic Belgian Army was clouded by the fall of the outer forts, was of European importance. 'they were messengers of hope, heralds of a sure though distant day of Belgian triumph. Before they came it seemed to the beleaguered saviors of civilization that they were forgotten of the world. But when the little British force arrived, they knew they were not forgotten, and the springs of energy in their soul were renewed. From Antwerp to Ostend, from Ostend to Nieuport, along Belgian Army's the Yser to Dixmude, the Belgian Army heroic resistance was to march in a glory of heroic resistance, exceeding anything in ancient or modern history. To have supported and encouraged men of this stamp in the darkest days of their campaign, is a great honor for a few thousand raw recruits to have won.

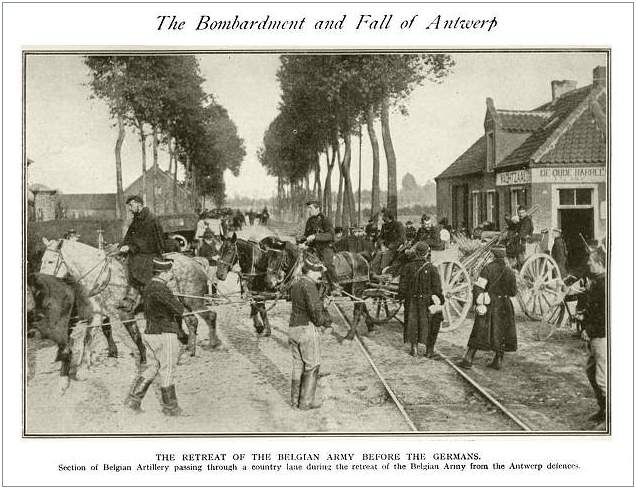

When the Germans had forced the passage of the Nethe, on the morning of Tuesday, October 6th, the defense of Antwerp was at an end. For General de Guise decided that the surrender of city was inevitable. It could have been delayed for a week or a fortnight, but only at the cost of the destruction of all the historic buildings of Antwerp, and the death or injury of thousands of towns people. Moreover, any prolonged resistance would endanger the Belgian Army and the British forces, as the Germans were now making attempts to cut the path of retreat between Ghent and the Dutch frontier.

In this region a hostile German army was operating, and another army corps was moving to support it. Beseler was at last doing the right thing from the point of view of the attacking side. He was relying on his siege train for the reduction of Antwerp, and allocating to the heavy guns and howitzers only sufficient infantry to protect the batteries from assault. He was swinging h]s main forces against the western flank of the Belgian - British lines where a series of fierce struggles were proceeding.

In these circumstances General de Guise arranged to hold the remaining forts and the inner line of defenses only so long as was necessary to cover the retreat of the allied troops. On Tuesday evening, therefore, the Belgian Army began to withdraw from Antwerp Cavalrymen and cycling carbineers, with armored motor-cars, crossed the Scheldt by the bridge of boats on the road to Ostend. Thirty large German steamers in the harbor were crippled by exploding dynamite in their cylinders and boilers. At daybreak on Wednesday morning the Belgian Government, with the Legations, left by steamer, transferring the capital of Belgium from Antwerp to Ostend. Mr. Winston Churchill also appears to have left that morning by motorcar, running under the protection of one of the armored cars with machine- guns which had proved so effective against German cavalry.

General von Beseler had given notice the evening before that he intended to bombard the city. The unhappy townspeople had gone to sleep on Tuesday night feeling confident that in a few days the Germans would raise the siege, as it was known that a new British force, under Sir Henry Rawlinson, was operating on their flank. But when the citizens went about their work the next morning they saw, with dread astonishment, on every wall a proclamation announcing the imminent bombardment. In the proclamation General de Guise recommended those who were able to depart to do so at once, while those who remained were advised to take shelter in their cellars behind sandbags.

It was the suddenness of the catastrophe, breaking in upon a period of renewed hope that took the heart out of many of the peaceful people of Antwerp. The population at the time was well over half a million for the city had become the refuge of some hundreds of thousands of fugitives from the shattered villages and bombarded towns of Belgium. In the famous stronghold of their nation they had thought they were at last safe from further attack by the host of murderers and torturers from Germany. Their nerves were already unstrung and their minds filled with terrible memories. So it is no wonder that some of them gave way to panic when they read the proclamation of doom.

Then began the immense, tragic flight of the inhabitants of Antwerp. Only three avenues of escape remained open - westward by road, to Ghent, Bruges and Ostend north-eastward by road into Holland, and down the Scheldt by water to Flushing Probably a quarter of a million escaped by river Anything that could float was crowded with the fugitives-merchant-steamers, dredgers, barges, and canal-boats, ferry- boats, tugs, fishing-smacks, yachts, rowing-boats, scows, and even hastily-made rafts. There was no opportunity of maintaining order and discipline. The terrorized people at times crowded aboard until there was not even standing room on the decks. Very few of them had brought food and warm clothing with them, or had space in which to lie down. For two nights and two days they huddled together, chilled and famishing, on the open deck, while the German guns bombarded the great, beautiful old city from which they had fled.

On the roads leading towards Ghent and the Dutch frontier the scenes of anguish and misery, hunger and fatigue, were even more appalling. In many places civilians and soldiers were mingled in inextricable confusion.

In the afternoon of October 7th the highway from Antwerp to Ghent was jammed from ditch to ditch. Every footpath and lane leading away from the invading army was so closely packed with fugitives that they impeded each other's movement. Young men could be seen carrying their frail old mothers in their arms, or helping their worn-out fathers by a pick-a-back ride. Wheelbarrows were sometimes used for this purpose, but more often they were packed with children too young to walk. There were monks in long, woolen robes, carrying wounded men on stretchers, and white-faced nuns shepherding along groups of war-orphaned infants.

Women still weak from childbed tottered along with their newly-born babes pressed to their breasts, their imaginations working almost to madness as they remembered the tales of what German soldiers had done to Belgian mothers and Belgian babes. Grey-haired men and women helped themselves along by grasping the stirrup-leathers of troopers, who were so exhausted from days of fighting that they slept in the saddle as they rode. Here a society woman, who had dressed at noon for a visit of fashion, stumbled along, carrying in a sheet on her shoulders her jewels and rich and heavy articles of precious metal. By her side was a frail, old lace-maker from Mechlin, whose bundle contained the simple, homely treasures of a cottage that no longer existed. The noise and the confusion were beyond mere imagination. The clamor was made up of the cries and shouts and moans of a nation in its agony. Men cursed their neighbors just to save themselves from weeping like women and amid their cursing, turned to help the poor creatures pressing against them. The heavy, quiet, slow-thinking, slow-moving Fleming, closely akin in origin to the Englishman, had been stampeded into terror. It was not the fear of death that moved him, but the fear of what the Germans might do to him and his women and children while life yet remained in their bodies. It was no rumors that shook him. lie had already spoken in Antwerp to fugitives from the blackened and gutted scenes of atrocities.

What especially added to the bitterness of the educated and directing class of townspeople was the memory of the part their city had played in crippling the national defense. It was from Antwerp that had come the strongest opposition to increasing the Army in the days when the German menace became apparent. Strategical railway lines had been constructed on the frontier, and every man in a responsible position in Belgium could see what was intended. But when the King and his Government proposed to reply to this threat against their neutrality by an increase iii troops and guns, Antwerp had been one of the principal opponents of the scheme. This was probably due to the fact that so many Germans had settled in the port that by various means they won a large control over the trend of public opinion. They had preached the gospel of pacifism, like true descendants of a former Prussian preacher against war- Frederick the Great, who wrote his Anti-Machiavelli " in order to still the suspicions of Europe until his army was ready to ravage Silesia. The similar movement of pacifism in our own country was no doubt headed by honest but deluded men, yet behind them a strong German influence could also be detected. If the Sea Lords of our Admiralty had not threatened to resign in a body in 1909, and thereby compelled the Liberal Cabinet to come its senses and defeat the German attempt to out build us in new battleships, that which happened in Antwerp might well have happened in London. Our politicians failed us as completely as the Antwerp politicians failed their people. We owe our present position, under God, to the firmness of character and keenness of vision of our Sea Lords of the year 1909. Thus, as a nation, we cannot in any way blame the people of Antwerp for failing, in the days of peace, to prepare for warlike defense We were deluded and almost betrayed, by the same subtle intrigues as ended in the disaster that overtook them.

It will never be known how many people perished from hunger, exposure, and exhaustion in the flight from Antwerp. The fields and ditches along the westward road were strewn with the prostrate bodies of outworn women, children, and old men. For miles around, the countryside was as bare of food as a sand desert is of flowers. There was not a scarcity of provisions, there was absolutely nothing to eat. The fugitives stopped at farmhouses and offered all they possessed for a loaf, but the farmers' wives, weeping at the misery of their own people, could only shake their heads. It was on raw turnips that the richest and the poorest stayed their hunger; and many who did not profit by the opportunity, when passing the turnip-fields had nothing. Near one small town on the Dutch frontier twenty children were born on Wednesday night in the open fields. The mothers were without beds, without shelter, and without medical aid. This occurred at a spot where an American observer chanced to be. At hundreds of other places along the lines of flight there were similar strangely piteous scenes, with no one even to record them.

As the fugitives were sleeping in the open air, on the night of Wednesday, October 7th, the bombardment of their city began. The first shell fell at ten o'clock, striking a house in the southern Berchem district, killing a boy and wounding his mother and his little sister. A street-sweeper lost his head as he ran for shelter ; it was blown off by the next shell. All through the night the shells fell at the rate of five a minute. Most of them were shrapnel shells, which shrieked over the house-tops and exploded with a rending crash in the streets. The object of the Germans was to kill and frighten the people rather than to destroy the buildings. So, though a few high-explosive shells were pitched into Antwerp, the bombardment was mainly carried out with shrapnel.

The idea, of course, was to terrorize the non-combatants so as to induce them to bring pressure upon the Belgian Government to surrender the Army and the city. But the persons who willingly remained to undergo the bombardment were not made of the stuff from which cowards are fashioned. Withdrawing into their cellars with food and candles, they protected the entrances with mattresses and pillows, and watched the night out with quiet fortitude.

In the meantime a large and gallant rearguard was holding the inner line of forts, and misleading the enemy by the stubbornness of its defense. For, with the British force, they still held some of the advanced trenches behind Fort Waelhem and Lierre, and though swept by a terrible shell fire, causing heavy losses, they kept oft the German infantry. Supported by the small old guns of the inner forts, and by the skillfully handled field-artillery of the Belgian Army, the heroic rearguard simply bluffed General von Beseler. Two days had passed since the German commander had forced the passage of the Nethe.

He had an absolutely overpowering number of guns and howitzers, and a much larger force of infantry than the Belgian commander had left behind. Had he only pressed forward, as any man with a backbone would have done in the circumstances, he would have captured the larger portion of the Belgian-British forces, together with hundreds of guns and large supplies of war material. But being a man with so highly-developed a sense of caution that it could not be distinguished from timidity, he wasted the two critical days in searching his path of advance with artillery fire.

He was apparently so afraid of falling into a trap and losing his large guns that nearly forty-eight hours passed before he brought them over the Nethe to bombard the city. By the evening of October 8th four of the inner line of forts had been badly battered from the western side of Antwerp, but the Allies still had the trenches two miles in front of these forts. No rushing attack was made on the belt of barbed-wire entanglements behind which our men and the Belgians were lying. Many of our volunteer naval reservists never saw a German. All their wounds were caused by shrapnel fire or shell splinters. - Somehow the wonderful system of German espionage seems to have got out of working order at the time when it would have been most serviceable. For, as we have seen, Beseler still had at least an army corps of men south of Antwerp, with a tremendous power of artillery to back them up.

With all the guns sweeping the forts and the spaces in between, where the Belgian field batteries were working, the position might have been carried at a loss of five or six thousand men. Beseler's infantry, however, had already suffered so heavily from Belgian rifle fire and machine-gun that he hesitated to attack.

The fact was, he suspected some sort of ambush, with perhaps land mines in the fields along his path, and concealed guns held in reserve. No other well-known German commander retirement has shown such a lack of courage in an important operation of the war, with perhaps the exception of General von Hausen when leading the Saxon army in the battles of the Marne. But if Beseler did not know when to move, the leaders of the Belgians and the British knew when to retire. In the evening of Thursday, October 8th, General Paris saw that if our Naval Division were to avoid disaster an immediate retirement under cover of darkness necessary. He consulted with General de Guise, the Belgian commander fully agreed with him. Thus final retirement began. All the night the British and Belgian troops crossed from the south of the city through empty streets, where the shells were falling thickly, passed over the Scheldt by the bridge of boats to the Ostend road.

Only the garrisons of the forts remained, working their guns with the utmost speed to engage the attention of the enemy, and frighten him from advancing on the city. Three of our battalions of the 1st Brigade of the Royal Naval Division-the Hawke, Collingwood, and Benbow battalion holding the trenches south of the town and one of the forts there, were left behind, as by some mistake or accident the order for retirement did not reach them. It was some time before they found they were deserted, and withdrew from the position which they had so gallantly held. Meanwhile, the other garrisons, while keeping up the pretence of resistance, were destroying their war material and putting their guns out of action one by one, so as not to excite the suspicion of the enemy. At dawn on Friday morning they also withdrew westward through Antwerp and towards Ghent and Ostend. Meanwhile the bombardment of the falling city was at its height. In the darkness before the dawn incendiary bombs rocketed across the wild and smoky sky and fell upon the houses. By this time the Germans had got some of their great howitzers within striking distance of the streets around the center of Antwerp

As the great shells hurtled through the air, they sounded at first like an approaching express train; but their roar rapidly increased in volume till the atmosphere quivered as before a howling cyclone. Then came an explosion, that seemed to split the earth, and a tall geyser of dust and smoke shot high above the stricken port. When a large high-explosive shell struck a building, it did not tear away its upper stories or blow a gap in the walls. The entire house collapsed in rubble and ruin, as though flattened by a monster's hand.

When the 11 in. shells exploded in the open streets, they made pits as large as the cellar of a good-sized house, and badly damaged any building within a radius of two hundred yards. The earlier shrapnel fire seemed harmless in comparison. It appeared as if in a few minutes the whole of the city would be wrecked as though by an earthquake. The thickest masonry crumpled up like cardboard; buildings of solid stone were leveled, as a child levels things he makes with playing-bricks when he has tired of them.

By Thursday night there was scarcely a street in the southern part of the city which was not barricaded by the wreck of fallen houses. The only quarter which escaped destruction was that which contained the handsome mansions of wealthy German residents of Antwerp in the Berckem district. The pavements were slippery with fallen glass. The streets were littered with tangled telephone wires, shattered poles, twisted lampposts, and splintered trees. More than 2000 houses were struck by shells, and more than three hundred of these were escape destruction totally destroyed.

Flames roared from many of the smitten dwellings. A hundred and fifty could be seen blazing away at the same time, and as the water supply was cut off there was no means of fighting these fires. Had there been a wind, everything in Antwerp would have been consumed, and nothing but the charred wreckage of one of the most beautiful and busiest centers of industry on earth would have remained in the hands of the conqueror. No military purpose was served by the bombardment of the city. Far more effectual results would have been obtained by concentrating all the artillery fire on the inner line of forts and the trenches and mobile batteries that barred the advance of the German infantry. Antwerp was partly destroyed with a view to terrorizing the peaceful population and filling their souls with the dread of the race that had burned and sacked Louvain and a score of smaller towns and villages in Belgium.

By night the scene was one of infernal splendor. The oil-tanks by the river had been fired by the retreating Belgians to prevent the conqueror making use of the large stores of petrol. The glare of the blazing oil illuminated the streets of this City of Dreadful Night. The lurid, wavering pillars of fire from the burning tanks, the flames of the bombarded houses, the flash and thunder of the exploding shells, turned lovely, romantic Antwerp into a spectacle of volcanic sublimity and terror. In the rivet the falling shells threw up columns of water a hundred feet towards the pall of smoke, which, rising from the tanks, overhung the city like a cloud of death, such as Vesuvius flung over Pompeii and Herculaneum. And all this scene of gigantic horror and woe and destruction was the work of men who pretended to the leadership of civilization.

Shells continued to fall on Friday morning, when a tall young man, in the plain uniform of a Belgian officer, took the rifle from a dead man in the trenches, leveled it, and shot at a German helmet. It was King Albert, the heroic leader of a nation of heroes, firing his last shot from Antwerp. By seven o'clock the last of the defending troops were believed to have crossed the river, and the bridge of boats was destroyed to prevent the enemy following them. After waiting an hour or two, to give the soldiers a good start, the burgomaster went out under a flag of truce to meet the German general and arrange the terms of surrender. It was reported that Beseler stated at the conference that, if the outlying forts were immediate surrendered, no money indemnity would be demanded from the city. A brilliant American war correspondent, who remained in Antwerp through the bombardment and took over the keys of German houses in the city from the American Consul and delivered these to the German authorities, makes the statement in question. If it is well founded, it shows how completely Beseler was deceived up to the last moment concerning the situation at Antwerp. For the forts had been abandoned, and they might have been taken by simply sending some soldiers to occupy them.

But the Germans were excessively cautious. At first Beseler only sent a few score of cycling troops into the city. They advanced very carefully from street to street and from square to square, until they formed a network of scouts. Behind them came a brigade of infantry, and hard on the heels of the infantry clattered half a dozen horse batteries. They galloped to the riverside, unlimbered on the quays, and opened fire with shrapnel on the last of the retreating Belgians, who had already reached the opposite side of the Scheldt In half an hour the pontoon bridge had been repaired, and on Friday night a large force of troops passed over in pursuit.

Some result might have been achieved if this belated operation had been continued with the utmost energy. But the German Staff was too much bent upon impressing the empty city to carry on the pursuit with vigor. The triumphal entry of the victors did not begin till Saturday afternoon, when 60 000 German soldiers marched into Antwerp. Westward towards the seacoast, from Lokeren to Ghent and from Ghent towards Ypres and Ostend, there was abundant work awaiting an -army of 60 000 young, vigorous soldiers. The Belgians were fighting their way to the sea ; part of the British Naval Division was being harried by the Dutch border; German forces were trying to cut the railway line on one side and to envelop the 7th Division of the British Expeditionary Force, under Sir Henry Rawlinson, on the other side.

Yet this was the time when 60 000 German troops were kept in Antwerp, to pass in review before the new military governor, Admiral von Schroder. Surrounded by his glittering staff, the admiral sat his horse in front of the Royal Palace, on which a Zeppelin had tried to drop bombs when the King and Queen of the Belgians were there. The spectacle of the great military pageant was strange and astonishing. Except for one American war correspondent and one American war photographer standing at the windows of the deserted American Consulate, the city was empty.

For five hours the mighty host poured through the ravines of brick and stone, company after company, regiment after regiment, brigade after brigade. There were ranks of gendarmes in uniforms of green and silver, Bavarians in dark-blue, Saxons in light-blue. and Austrians in silver-gray. The infantrymen, in solid columns of gray-clad figures, were neither Landsturm nor Landwehr, but young, red-cheeked athletes, singing as they marched.

Germany, Germany Over All! was the song they sang, each regiment headed by its band and colors. When darkness fell and the lamps were lighted, the shrill music of fifes, the roll of drums, and the rhythmic tramp of feet still continued.