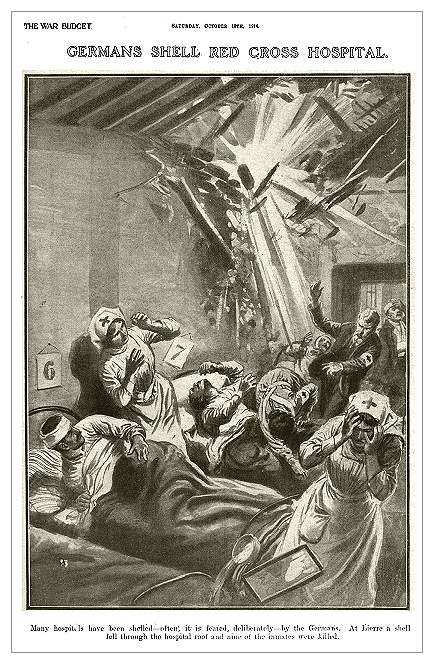

Bombardment of a Hospital at Lierre

Here follows a excerpt from the book 'A Surgeon in Belgium' which corroborates a story that appeared in a British news weekly magazine, 'The War Budget'. This story is illustrated in the magazine by a hand drawing and at first sight might appear to be a rather typical unsubstanciated 'atrocity' story, one of many which appeared in the media during the war. However in this instance we have the testimony of surgeon Souttar which accords well with the account published in 'The War Budget', even as to the number of victims.

"Lierre is an old-world town on the River Nethe, nine miles south of Antwerp, prosperous, and thoroughly Flemish. ….It is in no sense a military town, and has no defences, though there is a fort of the same name at no great distance from it.

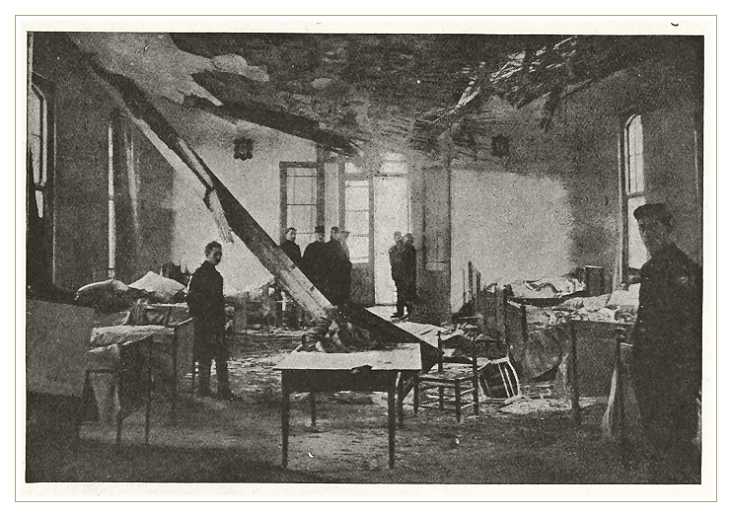

Into this town, without warning of any kind, the Germans one morning dropped two of their largest shells. One fell near the church, but fortunately did no harm. One fell in the Hospital of St. Elizabeth. We heard in Antwerp that several people had been wounded, and in the afternoon two of us went out in one of our cars to see if we could be of any service. We found the town in the greatest excitement, and the streets crowded with families preparing to leave, for they rightly regarded these shells as the prelude of others. In the square was drawn up a large body of recruits just called up - rather late in the day, it seemed to us. We slowly made our way through the crowds, and, turning to the right along the Malines road, we drew up in front of the hospital on our right-hand side. The shell had fallen almost vertically on to a large wing, and as we walked across the garden we could see that all the windows had been broken, and that most of the roof had been blown off. The nuns met us, and took us down into the cellars to see the patients. It was an infirmary, and crowded together in those cellars lay a strange medley of people. There were bedridden old women huddled up on mattresses, almost dead with terror. Wounded soldiers lay propped up against the walls; and women and little children, wounded in the fighting around, lay on straw and sacking. Apparently it is not enough to wound women and children; it is even necessary to destroy the harbour of refuge into which they have crept. The nuns were doing for them everything that was possible, under conditions of indescribable difficulty. They may not be trained nurses, but in the records of this war the names of the nuns of Belgium ought to be written in gold. Utterly careless of their own lives, absolutely without fear, they have cared for the sick, the wounded, and the dying, and they have faced any hardship and any danger rather than abandon those who turned to them for help.

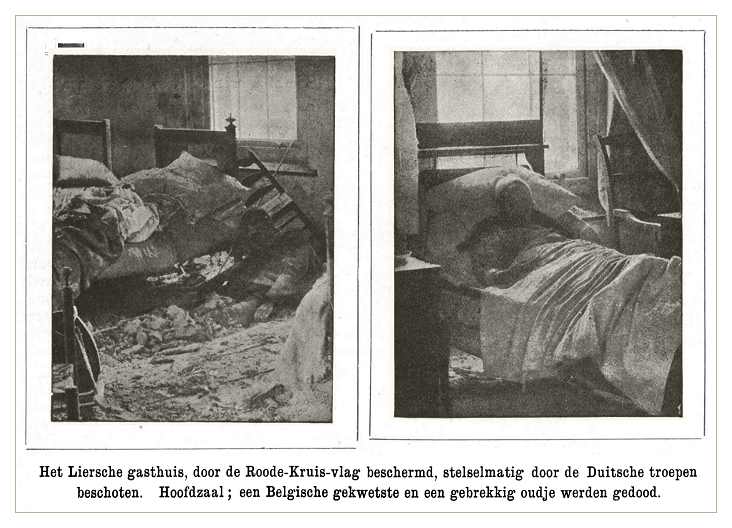

The nuns led us upstairs to the wards where the shell had burst. The dead had been removed, but the scene that morning must have been horrible beyond description. In the upper ward six wounded soldiers had been killed, and in the lower two old women. As we stood in the upper ward, it was difficult to believe that so much damage could have been caused by a single shell. It had struck almost vertically on the tiled roof, and, exploding in the attic, had blown in the ceiling into the upper ward. I had not realized before that the explosion of a large shell is not absolutely instantaneous, but, in consequence of the speed of the shell, is spread over a certain distance. Here the shell had continued to explode as it passed down through the building, blowing the floor of the upper ward down into the ward below. A great oak beam, a foot square, was cut clean in two, the walls of both wards were pitted and pierced by fragments, and the tiled floor of the lower ward was broken up. The beds lay as they were when the dead were taken from them, the mattresses riddled with fragments and soaked with blood. Obviously no living thing could have survived in that awful hail. When the shell came the soldiers were eating walnuts, and on the bed of one lay a walnut half opened and the little penknife he was using, and both were stained. We turned away sickened at the sight, and retraced the passage with the nuns. As we walked along, they pointed out to us marks we had not noticed before - red finger- marks and splashes of blood on the pale blue distemper of the wall. All down the passage and the staircase we could trace them, and even in the hall below. Four men had been standing in the doorway of the upper ward. Two were killed; the others, bleeding and blinded by the explosion, had groped their way along that wall and down the stair. I have seen many terrible sights, but for utter and concentrated horror I have never seen anything to equal those finger-marks, the very sign-manual of Death. When I think of them, I see, in the dim light of the early autumn morning, the four men talking; I hear the wild shriek of the shell and the deafening crash of its explosion; and then silence, and two bleeding men groping in darkness and terror for the air."

From ‘A Surgeon In Belgium’

by H.S.Souttar F.R.C.S. Late Surgeon-in-Chief, Belgian Field Hospital