the Belgian Army in Retreat to the Yser

The town of Dunkirk, from which I went out to many adventures in the heart of war, so that for me it will always hold a great memory, was on that day in October a place of wild chaos, filled with the murmur of enormous crowds, and with the steady tramp of innumerable feet which beat out a tragic march. Those weary footsteps thumping the pavements and the cobble-stones, made a noise like the surging of waves on a pebble beach - a queer, muffled, shuffling sound, with a rhythm in it which stupefied one's senses if one listened to it long. I think something of this agony of a people in flight passed into my own body and brain that day. Some sickness of the soul took possession of me, so that I felt faint and overcome by black dejection. There was a physical evil among those vast crowds of Belgians who had come on foot, or in any kind of vehicle, down the big, straight roads which led to France, and now struggled down towards the docks, where thousands were encamped.

From their weariness and inevitable dirtiness, from the sweat of their bodies, and the tears that had dried upon their cheeks, from the dust and squalor of bedraggled clothes, there came to one's nostrils a sickening odour. It was the stench of a nation's agony. Poor people of despair! There was something obscene and hideous in your miserable condition. Standing among your women and children, and your old grandfathers and grandmothers, I was ashamed of looking with watchful and observant eyes. There were delicate ladies with their hats awry and their hair dishevelled, and their beautiful clothes bespattered and torn, so that they were like the drabs of the slums and stews. There were young girls who had been sheltered in convent schools, now submerged in the great crowd of fugitives, so utterly without the comforts of life that the common decencies of civilization could not be regarded, but gave way to the unconcealed necessities of human nature. Peasant women, squatting on the dock-sides, fed their babes as they wept over them and wailed like stricken creatures. Children with seared eyes, as though they had been left alone in the horror of darkness, searched piteously for parents who had been separated from them in the struggle for a train or in the surgings of the crowds. Young fathers of families shouted hoarsely for women who could not be found. Old women, with shaking heads and trembling hands, raised shrill voices in the vain hope that they might hear an answering call from sons or daughters. Like people who had escaped from an earthquake to some seashore where by chance a boat might come for them all, these Belgian families struggled to the port of Dunkirk and waited desperately for rescue. They were in a worse plight than shipwrecked people, for no ship of good hope could take them home again. Behind them the country lay in dust and flames, with hostile armies encamped among the ruins of their towns.

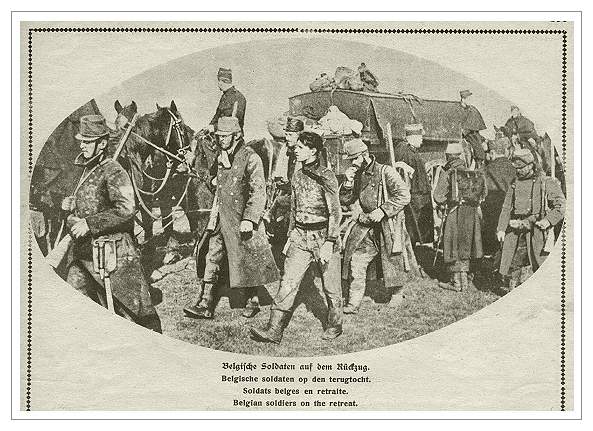

For a little while I left these crowds and escaped to the quiet sanctuary of a restaurant in the centre of the town. I remember that some English officers came in and stared at me from their table with hard eyes, suspicious of me as a spy, or worse still, as a journalist. (In those days, having to dodge arrest at every turn, I had a most unpatriotic hatred of those British officers whose stern eyes gimletted my soul. They seemed to me so like the Prussian at his worst. Afterwards, getting behind this mask of harness, by the magic of official papers, I abandoned my dislike and saw only the virtue of our men.) I remember also that I ate at table opposite a pretty girl, with a wanton's heart, who prattled to me, because I was an Englishman, as though no war had come to make a mockery of love-in-idleness. I stood up from the table, upsetting a glass so that it broke at the stem. Outside the restaurant was the tramp of another multitude. But the rhythm of those feet was different from the noise I had heard all day. It was sharper and more marked. I guessed at once that many soldiers were passing by, and that upon striding to the door I should see another tragedy. From the doorway I watched an army in retreat. It was the army of Antwerp marching into Dunkirk. I took off my hat and watched with bared head.

They were but broken regiments, marching disorderly for the most part, yet here and there were little bodies of men keeping step, with shouldered rifles, in fine, grim pride. The municipal guards came by, shoulder to shoulder, as on parade, but they were followed by long convoys of mounted men on stumbling horses, who came with heaps of disorderly salvage piled on to dusty wagons. Saddles and bridles and bits, the uniforms of many regiments flung out hurriedly from barrack cupboards; rifles, swords, and boots were heaped on to beds of straw, and upon the top of them lay men exhausted to the point of death, so that their heads flopped and lolled as the carts came jolting through the streets. Armoured cars with mitrailleuses, motor-cars slashed and plugged by German bullets, forage carts and ambulances, struggled by in a tide of traffic between bodies of foot-soldiers slouching along without any pride, but dazed with weariness. Their uniforms were powdered with the dust of the roads, their faces were blanched and haggard for lack of food and sleep. Some of them had a delirious look and they stared about them with rolling eyes in which there was a gleam of madness. Many of these men were wounded, and spattered with their blood. Their bandages were stained with scarlet splotches, and some of them were so weak that they left their ranks and sat in doorways, or on the kerbstones, with their heads drooping sideways. Many another man, footsore and lame, trudged along on one boot and a bandaged sock, with the other boot slung to his rifle barrel.

Riding alone between two patrols of mounted men was a small boy on a high horse. He was a fair- haired lad of twelve or so, in a Belgian uniform, with a tasselled cap over one ear, and as he passed the Dunquerquoises clapped hands and called out: "Bravo! Bravo!" He took the ovation with a grin and held his head high.

The cafés in this part of France were crowded with Belgian officers of all grades. I had never seen so many generals together or such a medley of uniforms. They saluted each other solemnly, and there were emotional greetings between friends and brothers who had not seen each other after weeks of fighting in different parts of the lines, in this city across the border. Most of the officers were fine, sturdy, young fellows of stouter physique than the French among whom I had been roving. But others had the student look and stared mournfully from gold-rimmed spectacles. There were many middle-aged men among them who wore military uniforms, but without a soldier's ease or swagger. When Germany tore up that "scrap of paper" which guaranteed the integrity of Belgium, every patriotic man there volunteered for the defence of his country and shouldered a rifle, though he had never fired a blank cartridge, and put on some kind of uniform, though he had never drilled in a barrack square. Lawyers and merchants, schoolmasters and poets, actors and singers, farmers and peasants, rushed to take up arms, and when the vanguards of the German army trekked across the frontier they found themselves confronted not only by the small regular army of Belgium, but by the whole nation. Even the women helped to dig the trenches at Liege, and poured boiling water over Uhlans who came riding into Belgian villages. It was the rising of a whole people which led to so much ruthlessness and savage cruelty.

The German generals were afraid of a nation of franc-tireurs, where every man or boy who could hold a gun shot at the sight of a pointed helmet. Those high officers to whom war is a science without any human emotion or pity in its rules, were determined to stamp out this irregular fighting by blood and fire, and "frightfulness" became the order of the day. I have heard English officers uphold these methods and use the same excuse for all those massacres which has been put forward by the enemy themselves. "War is war. . . . One cannot make war with rosewater. . . The franc-tireur has to be shot at sight. A civil population using arms against an invading army must be taught a bloody lesson. If ever we get into Germany we may have to face the same trouble, so it is no use shouting words of horror."

War is war, and hell is hell. Let us for the moment leave it at that, as I left it in the streets of Dunkirk, where the volunteer army of Belgium and their garrison troops had come in retreat after heroic resistance against overwhelming odds, in which their courage without science was no match for the greatest death machine in Europe, controlled by experts highly trained in the business of arms.

That night I went for a journey in a train of tragedy I was glad to get into the train. Here, travelling through the clean air of a quiet night, I might forget for a little while tile senseless cruelties of this war, and turn my eyes away from the suffering of individuals smashed by its monstrous injustice.

But the long train was packed tight with refugees. There was only room for me in the corridor if I kept my elbows close, tightly wedged against the door. Others tried to clamber in, implored piteous]y for a little space, when there was no space. The train jerked forward on uneasy brakes, leaving a crowd behind.

Turning my head and half my body round, I could see into two of the lighted carriages behind me, as I stood in the corridor. They were overfilled with various types of these Belgian people whom I had been watching all day - the fugitives of a ravaged country. For a little while in this French train they were out of the hurly-burly of their flight. For the first time since the shells burst over Antwerp they had a little quietude and rest.

I glanced at their faces, as they sat back with their eyes closed. There was a young Belgian priest there, with a fair, clean-shaven face. He wore top boots splashed with mud, and only a silver cross at his breast showed his office. He had fallen asleep with a smile about his lips. But presently he awakened with a start, and suddenly there came into his eyes a look of indescribable horror. . . . He had remembered.

There was an old lady next to him. The light from the carriage lamp glinted upon her silver hair, and gave a Rembrandt touch to a fair old Flemish face. She was looking at the priest, and her lips moved as though in pity. Once or twice she glanced at her dirty hands, at her draggled dress, and then sighed, before bending her head, and dozing into forgetfulness.

A young Flemish mother cuddled close to a small boy with flaxen hair, whose blue eyes stared solemnly in front of him with an old man's gravity of vision. She touched the child's hair with her lips, pressed him closer, seemed eager to feel his living form, as though nothing mattered now that she had him safe.

On the opposite seat were two Belgian officers - an elderly man with a white moustache and grizzled eyebrows under his high kepi and a young man in a tasselled forage cap, like a boy-student. They both sat in a limp, dejected way. There was defeat and despair in their attitude It was only when the younger man shifted his right leg with a sudden grimace of pain that I saw he was wounded.

Here in these two carriages through which I could glimpse were a few souls holding in their memory all the sorrow and suffering of poor, stricken Belgium. Upon this long train were a thousand other men and women in the same plight and with the same grief.

Next to me in the corridor was a young man with a pale beard and moustache and fine delicate features. He had an air of distinction, and his clothes suggested a man of some wealth and standing. I spoke to him, a few commonplace sentences, and found, as I had guessed, that he was a Belgian refugee.

"Where are you going ?" I asked.

He smiled at me and shrugged his shoulders slightly. "Anywhere. What does it matter ? I have lost everything. One place is as good as another for a ruined man."

He did not speak emotionally. There was no thrill of despair in his voice. It was as though he were telling me that he had lost his watch.

"That is my mother over there," he said presently, glancing towards the old lady with the silver hair. "Our house has been burnt by the Germans and all our property was destroyed. We have nothing left. May I have a light for this cigarette ?"

My young soldier explained the reasons for the Belgian debacle. They seemed convincing

"I fought all the way from Liege to Antwerp. But it was always the same. When we killed one German, five appeared in his place. When we killed a hundred, a thousand followed. It was all no use. We had to retreat and retreat. That is demoralizing."

"England is very kind to the refugees," said another man. "We shall never forget these things."

The train stopped at wayside stations. Sometimes we got down to stamp our feet. Always there were crowds of Belgian refugees on the platforms - shadow figures in the darkness or silhouetted in the light of the station lamps. They were encamped there with their bundles and their babies.

On the railway lines were many trains, shunted into sidings. They belonged to the Belgian State Railways, and had been brought over the frontier away from German hands - hundreds of them. In their carriages little families of refugees had made their homes. They are still living in them, hanging their washing from the windows, cooking their meals in these narrow rooms. They have settled down as though the rest of their lives is to be spent in a siding. We heard their voices, speaking Flemish, as our train passed on. One woman was singing her child to sleep with a sweet old lullaby. In my train there was singing also. A party of four young Frenchmen came in, forcing their way hilariously into a corridor which seemed packed to the last inch of space. I learnt the words of the refrain which they sang at every station:

- A bas Guillaume !

- C'est un filou.

- Il faut le prendre

- Il faut le pendre

- La corde a son cou !

The young Fleming with a pale beard and moustache smiled as he glanced at the Frenchmen. "They have had better luck," he said. "We bore the first brunt."

I left the train and the friends I had made. We parted with an "Au revoir" and a "Good luck !" When I went down to the station the next morning I learnt that a train of refugees had been in collision at La Marquise, near Boulogne. Forty people had been killed and sixty injured.

After their escape from the horrors of Antwerp the people on this train of tragedy had been struck again by a blow from the clenched fist of fate.

- * see also A British Reporter at Furnes