see also : 'Les Rats Plaie des Tranchées'

RATS

One cold, wet, winter's day the ambulance packed up and, at the rear of the division, marched away from the enemy, the tumult and the mud of the Salient, in the direction of Cassel. Late in the afternoon we arrived at the village of Steenvoorde where we were to be billeted. Bob Church, my batman, whom I had sent on ahead, had managed to get me a bedroom at the house of some old friends of mine, Monsieur and Madame Schatt. I had often been billeted on them before. Their house stood in the main street, and their two charming daughters ran one of those amateur shops which were so popular with British officers, where all sorts of trifles from electric torches to scented soap could be purchased at double their proper price.

As a friend of the family I was given the best spare bedroom with the unwonted luxury of sheets in the bed. Rain and sleet were beating on the window when I woke up next morning, so I decided as there was no work to be done to make the most of the sheets, and spend a day in bed. I told Bob if any one inquired for me to say I was in bed with a bad cold and could not be disturbed.

The morning was passing very comfortably, as I lay between the sheets, smoking and reading, when all of a sudden I became aware of a disturbance outside my room, of loud voices expostulating. A moment later the door was flung open and in strode a small but fierce-looking officer. His cap showed him to be a staff officer of some kind, but as he was wearing a long waterproof coat over his tunic, I could not tell his rank. Now in the army the manner in which a conversation takes place between any two officers largely depends on the relative rank of the speakers. Thus it was I found myself in some difficulty. But the small staff officer quickly came to the point, for after glancing at a paper in his hand he demanded, "Are you Captain P. H. G. Gosse, R.A.M.C.?"

"Yes," I admitted, though wondering whatever it was all about.

“Well," continued the staff officer, "am I right in under-standing you know all about rats?"

Now that, I thought, is a strange question to be asked by a total stranger, still more so when you are lying in bed. I wondered what was at the back of it, and whether it might lead to some nice quiet job or if I was to be court-martialled for a pastime so unbecoming an officer and a gentleman as skinning mice. Like everybody else who had been in the line for any length of time, excepting those rare and to be envied blood-lust soldiers who enjoyed the War, I was all for a safe and cushy post if such was offered me.

But this odd question," You know all about rats?" No. I wanted to learn a little more before giving a definite answer. So to gain time I replied, "Well, I know a good deal about birds."

“That's excellent," said he. "You are appointed Rat Officer to the Second Army and will report forthwith to the Director of Medical Services to the Second Army at Hazebrouck," whereupon, without waiting for any further observations from me or bidding me farewell or even expressing any interest in my bad cold, the fierce one right-about turned and marched out of the room.

“So here is a pretty how-d'ye-do," I thought as I lay back again between my warm sheets.

My meditations, however, were soon interrupted by the return of Bob Church, to whom I described what had happened during his absence and asked him what he thought about it all.

"Think about it?" said Bob. "Don't you waste no time, sir, thinking, we've got a cushy job, and mustn't miss it," whereupon, without another word, my batman fell upon his knees and began with feverish haste to pack my valise, folding camp bed, washstand and arm-chair, and of course the precious specimens, traps and skinning instruments.

In no time we were off in a borrowed motor ambulance to Hazebrouck, where I reported my arrival at Headquarters and was introduced by the fierce one - he proved to be a temporary Major R.A.M.C. - to General Porter, the D.M.S., who formally appointed me Rat Officer to the Second Army. The appointment was to be a temporary one and an experiment, and would not carry with it any promotion in rank nor any emoluments.

He told me that instructions had reached him from higher up to find a suitable officer for the post and that having heard of my activities - that was the word he used, which was accompanied by what looked uncommonly like a wink-he thought I ought to do.

A very pleasant and interesting post it proved to be, while it lasted. First of all there was no precedent to be followed, and King's Regulations contained no mention even of a rat officer, what he should or should not do. This was most encouraging, since almost every form of military initiative appeared to me to be hampered by some rule or formula in King's Regulations.

For more than two years people like myself had been pulled up by King's Regulations, and arguments with quartermasters had always ended by the old hand producing a copy of King's Regulations and finding something there with which to confound one.

Now I had a clear field to work in, with no rules, regulations or precedents. To begin with I was told to draw up a general scheme to show what damage rats did, and whether they were a possible source of danger to the health of the army, and to offer suggestions for dealing with the plague of rats which swarmed in and behind the trenches.

In such a war as this where two vast armies had been entrenched for over two years, rats were everywhere; not only in the trenches but all over the back areas where troops were quartered. This enormous increase in the rat population was brought about as is always the case by two factors which had upset the balance between the natural enemies of rats and the rats' food supply.

In peace time every man's hand had been against the rat: every farmer took some means or other to keep him in check, if not to exterminate him, while most houses had a cat or a dog which also helped. But when the armies came most of the farmers left, and for some mysterious reason the dogs as well - the French peasants said the English soldiers took them, and not without some justification, for almost every British battalion was accompanied by a small pack of mongrel mascots wherever it went. But probably the most important reason for the increase of rats was food. The British army was supplied with a vast surplus of rations, much more than could be consumed. Food, stale bread, biscuits and particularly cheese, littered the ground. Some quartermasters, to save themselves trouble and to guard against any risk of being caught without enough, would indent for greater quantities of rations than they required or were entitled to. This surplus was disposed of in different ways. Much of it went to feed hungry Belgian and French children, at which nobody could complain; as much again was thrown on the rubbish heap, burnt in the incinerators or buried in pits when a battalion moved from its camp.

It is a well-known fact that if rats are well fed they breed more often and have bigger litters. Given ideal conditions the number of descendants from one original pair of rats is appalling. It has been calculated that a pair of rats in such ideal conditions will produce eight hundred and eighty offspring in one year, truly a staggering figure.

One glaring example of how our rations were wasted was brought to my notice while I was acting as M.O. to the 9th Yorks, when their own M.O., Rix, was on leave. The battalion had just come out of the line and I was ordered to join the headquarters staff mess at a small house on the Armentieres-Sailly road. It was a winter's day and when we arrived at the house we found no fire in the mess-room, which was bitterly cold. The colonel sent word to the lady of the house to ask if she could supply us with some firing until the cooks and servants arrived with the mess-cart. In a few minutes Madame entered the room with her apron full of material for making a fire. First she laid in the grate some crumpled pieces of English newspaper and a few pieces of wood. On top of this she built up a sort of open-work pyramid of army oatmeal biscuits. On top of these again she placed a few pieces of coal, applied a match to the paper and in no time we had a roaring fire. I did not know until then what a combustible thing an oatmeal biscuit was. But all the same, it did seem a wicked waste of good food. When we expostulated with Madame, and asked her why she used biscuits as kindling, she replied, "Ils sont tres bons pour allumer un feu."

Having got my instructions from the D.M.S., my batman and I settled down at Hazebrouck in some comfortable billets with a French family, and I got permission to have my meals with them instead of messing with one of the headquarters staff.

I now sat down to write a learned treatise on the natural history of the Brown Rat - Epimys norvegicus - going fully into its habits and marriage customs, and dwelling on the enormous destruction it did to army food as well as army equipment.

I also dealt, but not at such length, with the Black Rat - Epimys rattus - and pointed out how it might become a carrier of Bubonic plague.

I then proceeded to draw up, but not in detail, several schemes for destroying rats: by poison, by gas and by traps. In theory I slaughtered rats in their thousands and their hundreds of thousands.

I ended my report by pointing out that all methods for the extinction of rats would fail if at the same time proper measures were not taken to prevent the rats getting at food, which I advised should be done by keeping all eatables whether in bulk, or only in small quantities as in dug-outs, in rat-proof cages or cupboards.

When this great treatise was completed to my satisfaction I laid it, not without some feeling of pride, before the General and retired to await his verdict. A few days afterwards I was sent for and informed that my report had been read at head-quarters and, with the exception of one part, approved of.

The part objected to was the proposed plan to exterminate the rats by means of poisoned food, which was considered a possible danger to the troops. I was now told to draw up another scheme for a big campaign against the rats in the whole of the Second Army area by means of traps and to give exact details how the traps should be used and by whom. This was a pretty large order, but nothing daunted, I applied for leave to proceed - one always ‘proceeded’, never ‘went’ - to Paris, in order to consult with the French army authorities and learn what they were doing about the rat menace. I had read an article in the Morning Post written by Mr. H. Warner Allen, the representative of the British press with the French Army, in which it was stated that in one army corps a reward of one sou was offered for each dead rat brought in from the trenches, and that in one fortnight 8,000 rats were killed and the rewards claimed.

This plausible proposal for a liaison visit to Paris was at once turned down and the next best I could obtain was the use of a car to take me to the Base to interview the Head of all the Quartermasters about supplying the particular type of rat trap I recommended should be used.

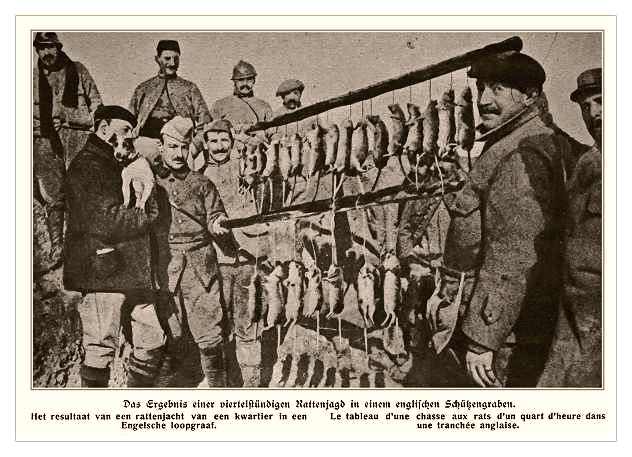

hunting rats in the French lines

It was a pleasant drive from Hazebrouck through Hesdin to the coast. What first struck me when I arrived at the outer office of this high official was the brave display of war decorations. Every military clerk seemed to be wearing at least one ribbon on his tunic. The sergeants had all won the D.C.M. and M.M. with a pretty spattering of French and Belgian ribbons Most of the corporals wore a military medal, and some a foreign decoration as well. How brave and how clean they all looked after the unclean, undecorated men I had lived amongst for the last two years, where an occasional Military Medal or even rarer Distinguished Conduct Medal was a thing to notice and admire.

Having at length broken through this barrage of heroes I was ushered into the Presence, and stood at attention before the great man himself. After the usual frigid reception - I was getting used to being greeted in this manner and was no longer intimidated by it - I explained my business, and soon found him to be a most pleasant and intelligent man. I put before him the pros and cons for the type of trap I thought best and he promised to let me have - I forget how many thousands - of the sort I wanted; and I returned triumphantly to Hazebrouck.

This habit of the Great I have just referred to, of receiving junior officers as though they were the very dregs of society, or had just been detected committing some foul crime, I found very disconcerting, indeed terrifying when I first experienced it. But gradually I discovered that most of the Great, and all the less great, began in that way and that really it meant nothing at all, for more often than not they would soon be cracking jokes or at least being quite polite. The secret of success lay in refusing to be bullied, and it was from a big-game hunter who ran a school of sniping at Mont des Cats that I learned the secret. His advice to me was to treat a General, a Brigadier, or a full Colonel exactly as you would a lion or any other fierce beast of prey. That is to say, however scared you might be you must not on any account let him see you were frightened, and above all, never for one moment take your eye of him. Once this lesson was learned I found no trouble in dealing with the most fiery of senior officers, even non-combatant ones.

Well do I remember one scene of frightfulness which verified the proverb that every flea on the dog's back has a lesser flea to bite him. On that occasion I was the smallest and the least of all the fleas present. It was one afternoon at Fort Rompu. Suddenly, without warning, there was an eruption of "brass-hats." Our Colonel, Nimmo Walker, was away up the line and I was in charge of the ambulance. Never before had I seen such a galaxy of military doctors of high degree. I am not sure who they all were, but at their head was General MacPherson, known, respected and loved throughout the R.A.M.C. as "Fighting Mac." Following him came the D.D.M.S. corps, with various other medical officers, including the divisional A.D.M.S. and his D.A.D.M.S.

What all the trouble was about I forget, but I was asked a question to which I gave what I thought was the right answer.

Instantly the A.D.M.S. reprimanded me, and before all those great men I was humiliated. But hardly had the words passed the lips of the A.D.M.S. when the D.D.M.S. contradicted him and said that both he and I were wrong. But the D.D.M.S. was not to have the final word, for Fighting Mac in a voice which filled the whole building proceeded to "tell off" the D.D.M.S. and then the A.D.M.S. and did so in no half measures. When I thought my turn was coming, I drew myself rigidly to attention to receive my "dressing down" in soldierly fashion, when "Fighting Mac" sprung a pleasant surprise on my by saying,

"As for you, Lieutenant Gosse, I absolutely agree with what you did and with the answer you gave," and turning to the A.D.M.S., told him to make a note of it, and the august group swept out, leaving me shaken but happy.

Several years after the War I was one day talking to an affable looking member of mildly military appearance, in the billiard-room of the Savile Club. I had not the least idea who he was, although we often sat and talked together. Somehow or other his name happened to be mentioned, and I found that this gentle person was no other than the terrible 'Fighting Mac'. I could not resist the temptation to remind him of the scene of ruthlessness at Fort Rompu, which he laughed over but pretended to believe I had invented.

Drawing from a German magazine

While organising my rat campaign I had to travel far and wide over the Army area, interviewing all manner of officers from proud brigadier generals to auspicious quartermasters. The latter were by far the more difficult to deal with. Not only were they suspicious - there was nothing about rat-catchers or catching rats in K.R. - but they particularly resented any assumption on my part that their stores might be better if they were protected from rats by wire-netting. Considering that by this tune almost every quartermaster a store had become so swarming with vermin as to be a sort of combined House of Commons, Queen Charlotte's Lying-in Hospital and R.A.C. for rats rolled into one, it might have been thought that any suggestions to improve matters would be welcomed. But this was far from being the case.

Through making these visits I got a very shrewd idea of what it must be like to be a commercial canvasser. The commercial canvasser when he rings the house bell must wonder if he will be hurried away without a hearing, or if not, what sort of a person and reception he is about to meet. I had one great advantage over the commercial canvasser in that I could not be turned away without being seen and heard, because all my clients had received warning - probably in triplicate of my intended visit and instructions to assist me.

Where the fun came in was to observe the manner of the first salutation. A few of the regular R.A.M.C. colonels were frankly rude at the start, while most of the territorial R.A.M.C. colonels were usually the opposite. I think the former classed a Rat Officer with a rat-catcher and that the greeting I so often received was the rat-catcher greeting. Though why any one should be rude to a rat-catcher I do not know. The few professional rat-catchers I have been privileged to meet, either in business or socially, have all been interesting men with charming manners, but perhaps being members of the same craft or mystery may have helped to put us on a friendly footing.

My whole time was not taken up paying these visits, for as G.O.C. rats, I had to deliver lectures. These began in a quite small way at Hazebrouck, where a school of sanitation for officers had been started and where courses of lectures were delivered by various experts, each on his own special subject. Last but two on the syllabus of subjects, came mine on rats; the two even lower on the list being flies and parasites, the experts on which were familiarly referred to as O.C. Maggots and O.C. Lice. The audiences consisted of officers, some of them regimental medical officers, but for the most part young combatant officers belonging to various infantry regiments, artillery brigades, Royal Engineers, machine-gunners, Army Service Corps, etc., in the Second Army. Until my lectures became better known my reception by my pupils was invariably chilly. No bones were made about letting me see that I was wasting g their time by talking about rats, time which could and should have been so much better and more agreeably occupied in other ways; some not unconnected with those cafés, half club, half brothel, which provided drink for the thirsty on the ground floor and solace for the bored upstairs. But it was gratifying to the lecturer to observe the gradual change from undisguised boredom to attention, then to interest, until finally the audiences actually became enthusiastic.

On the days I was to lecture I used to lunch at the Coq d'Or, a comfortable old-fashioned hotel in the Grand Place. In happier days before the war the local Flemish farmers probably met there for their "ordinary." Down the middle of the big dining-room ran a long table. By common consent one half of this table was occupied by the farmers, the other by the British officers who were stopping at Hazebrouck for the course. During one dejeuner in Ia fourchette, a youthful officer, I think he was in trench mortars but cannot now be certain, asked the company in general what was "on" that afternoon, to which another equally juvenile warrior, a second lieutenant in machine-guns, replied, "Oh some bloody old fool is going to talk a lot of bunk about rats." I dropped my eyes to my plate but kept my ears open. The subject of my lecture at once became the topic of general conversation, and I soon learned that both the unheard lecture and the unheard lecturer were beyond the pale, but no one spoke more bitterly nor more frankly about both than the machine-gunner. Many different points of view were expressed about myself and my lecture, but the unanimous verdict was that it was a scandal that officers like themselves should be compelled to waste their time and rare leisure listening to a silly lecture about rats. Who in any case wanted to be told anything about rats; had they not seen all the rats they wanted to in the trenches, and why could they not be allowed for once to forget about rats ?

Half an hour later I stepped on to the raised platform in the lecture-room. Exactly opposite to me, in the middle of the front row, was seated the young machine-gun officer. Our eyes met in mutual recognition. He knew that I knew, and I knew that he knew I knew. How uncomfortable he looked, truly I felt sorry for him, for I quite saw his point of view. But he and I were not the only two in that room who appreciated the situation, a feeling of electricity pervaded the hall.

“Gentlemen," I began, "Just now while at lunch at the Coq d'Or, one officer asked another what was on this afternoon. The other officer, whom I observe seated amongst you replied," - here a stern look at the crestfallen lieutenant - “ ‘Some bloody old fool is going to talk a lot of rot about rats.' However," I continued, "I bear him no malice and only hope that he will find my lecture not as dull as he expected nor think me quite such an old bore as he feared."

This opening being greeted with applause, permission to smoke was given, the lecture began, and in no time we were all as jolly as jolly could be. At the end of the lecture, the machine-gun subaltern and I had a friendly chat, about all sorts of things, including rats, and parted the best of friends.

This lecture became in time, if I may be allowed to say so, a feature of the War, and the envy of the other armies of the B.E.F., which had neither a rat officer nor rat lectures. Like many other successful concerns, such as Toc H or the B.B.C. or Sir Josiah Stamp, the rat lectures began in quite a small way, to grow and expand into a flourishing undertaking.

At first the lectures were given only to officers, but soon classes were formed for men as well. Gradually I learned to modify the lecture to the two different audiences. I found that some facts and little jests which interested or amused the officers fell flat with the men, and vice versa. So both clients were catered for. Not the least feature, modesty prevents me calling it an attraction, of the lectures was the table of exhibits. On this table were arranged specimens I had caught and stuffed of most of the small mammals to be met with in or behind the trenches, as well as models and drawings of traps. To most of those who saw these it came as a surprise to learn how many different animals there were in Northern France, believing as they did that the brown or trench rat was the only beast but man to be found in Flanders. Amongst the exhibits were moles, hedgehogs, common shrews, pigmy shrews, water shrews, white-toothed shrews, garden shrews, weasels, stoats, pole-cats, bank voles, subterranean voles, orchard dormice, wood-mice, harvest mice, rabbits and pipestrell bats. When the fame of the lecture had spread abroad I used to be invited to deliver it - with, of course, the exhibits - to various gatherings. In fact, my lecture became in time to be looked upon as a sort of drawing-room entertainment, and I went about from place to place giving performances much in the way conjurers and ventriloquists do, who give refined entertainments at children's Christmas parties.

By this time, early 1917, schools had become all the rage. Besides schools of sniping, bombing and musketry, there were academies where short courses of instruction were held in bayonet fighting, trench mortars, poison gas, and the construction of latrines and incinerators. Not to be beyond the times, the Xth Corps opened a school of sanitation at Vieuxbec, near Poperinghe, and sent me there to help to run it. Although not many miles away from the line the village was happily free from evidence of warfare, beyond a few British soldiers and an occasional passing army lorry; while the country round was pretty, with several small but steep wooded hills, delightful rarities in that flat and treeless land.

The staff of the new school consisted of two R.A.M.C. officers and several N.C.O.'s. The senior, my chief, was a cheerful North of Ireland doctor who before the war had been a medical officer of health at Belfast, so that at least one of the staff knew something, and more than something, about the subject we were to teach. Together we started and ran the school, and he was as anxious as I to make the weekly course not only useful but as pleasant and happy as possible for our pupils.

Lectures and demonstrations were given by us both on every conceivable subject relating to public health. By instructions from headquarters the title of my, by now, famous discourse on rats was altered to 'A Lecture on Zoology in its Relation to Sanitation', but I also lectured on lice, fleas, bugs and blue-bottles, trench-foot, its cause and prevention, food, latrines, kitchens, incinerators, grease-traps and cooking. In vain I expostulated against having to lecture on cooking, not merely because I knew nothing about the subject but because a number of our pupils each week were cooks. When I say I knew nothing about the subject of cooking perhaps I do myself an injustice. I knew how to make an omelette with eggs and bread crumbs, a secret divulged to me when a boy by Mr. Harold Cox, and one I had kept jealously ever since. But at a class of cookery you cannot go on day after day, week after week, teaching nothing else but how to make an omelette of eggs and bread crumbs, so I procured a copy of Mrs. Beeton's classic work and crammed up a few simple recipes which seemed to lend themselves to army rations. As a matter of fact we invented several new dishes out of bully beef, Maconochie ration and potatoes, and even made excellent cakes, although nothing surpassed our famous bully beef and biscuit rissoles. All our experiments were tried on our pupils, and some of them were voted satisfactory, and the army cooks returned to their units with many culinary surprises up their sleeves.

The whole of our time was not taken up with lectures and demonstrations. One of my duties, and the one I liked best, was to take the entire class, some fifty men, for a daily march for the benefit of their health. This came under the heading of drill in the syllabus, but it seemed to me incongruous and presumptuous for me, an R.A.M.C. officer and a non-combatant, to drill fifty men on the barrack square, and also I never could remember any words of command other than "Shun; move to the right in fours, form fours, right, by the right quick march." Beyond this string of words, which any parrot of average intelligence would pick up in a few days, I knew nothing, so that whenever I was in command of a company, section or party of soldiers, it simply had to march away or go round in circles. Having got my little army moving I would march at the head and lead them straight up the side of the nearest hill, where I would give them a short "breather," and then, like the grand old Duke of York, lead them down again on the other side as fast as they could run, getting in a few jumps over hedges and banks to lend excitement.

Of course there were bound to be one or two of the usual "grousers" who complained at first, but they would soon see the fun of the whole thing and enter into it with the rest. When we got back, dinner would be ready, and thanks to Mrs. Beeton there was generally some surprise in store, and the men thoroughly enjoyed the change from the monotonous, unappetising fare they were accustomed to.

The pupils were encouraged to ask questions after the lectures and, at the end of the" Zoological" one, the questions often developed into a general conversation on natural history. Now and them one of the men would try to catch me out, and if I was able to score off him instead the audience was delighted.

Some of the soldiers who were country bred used to ask very intelligent questions, or tell me interesting first-hand experiences of their own. One day, at the rat lecture, the talk had somehow drifted to hedgehogs and I referred to the popular country belief that hedgehogs sucked the milk of cows. I told them that there was no proof of such an improbable occurrence, and that I had never met anybody who claimed to have seen such a thing happen. At the end of the lecture a tall, rough-looking man stood up and said he knew it to be a fact that hedgehogs sucked the milk of cows, because he himself had seen it done. This bold challenge caused an instantaneous sensation, and I invited the man to tell the audience all about it. He said that very early one morning, just before dawn, he and a friend at home in Northumberland were walking along the edge of a meadow beside a coppice. Several cows were lying down and he and his friend saw a hedgehog sucking the teat of one of the cows. I knew well enough the man was only trying to" score off me "so I asked him " What exactly were you and that friend of yours doing at dawn by that coppice? " The soldier, turning red in the face, collapsed into his seat amidst laughter and cries of " poacher," and I got out of it all right and was more than even with my would-be tormentor.

It was a pleasant surprise to find how keen these soldiers were on natural history. At first, I feared they would be bored with anecdotes about birds and beasts, but the majority seemed very interested. After one of the lectures on rats a middle-aged man from a Yorkshire regiment told me how, quite recently, he had entered a wrecked church at Ypres in search of some wood to make a fire with. He found and pulled some down behind the ruined altar, and in doing so uncovered a large bat asleep. After carefully examining the bat he put it into a box, and afterwards laid the box near the fire he had made. After a while, the warmth of the fire - this happened during very cold weather - awakened the bat, which began to scramble about in the box, so the soldier let it out and it flew away.

This little anecdote had a sequel.

Ten minutes later the soldier who told me about his large bat brought up to me another soldier, to whom he had never spoken before but who had overheard us talking about the Ypres bat. The newcomer, after explaining to me that he was "fond of animals," produced a grubby little pocket diary and showed me this entry for January 2nd, 1917: "Saw to-day a large bat flying about the streets of Y. Probably disturbed by shellfire." By comparing notes the two soldiers had found that they both saw the big bat on the same day and about the same hour, and it was a truly strange coincidence that they should have met at my lecture at Vieuxbec.

I fear that there was a sad lack of discipline at our lectures, but all the same the pupils never got out of hand or took advantage of our good nature, and during the whole time the school lasted we never once had to punish a man. Only once was I embarrassed by the heartiness of the applause of my pupils. It was one afternoon when delivering the rat lecture to a particularly bright and sympathetic class. To bring the lecture to a happy termination I told them the famous story of Darkie's rat.

It should be explained that the most popular estaminet in Vieuxbec was the Réunion des Blanchisseuses, ruled over by Madame Perret with the assistance of a big tousled Flemish hoyden called Darkie. This girl, not without good looks of a sort, was a great favourite with the soldiers. My friend, Monsieur Junod, the French interpreter, was billeted at the estaminet and unlike most Frenchmen was a keen naturalist and took great interest in helping me devise and make various types of rat traps. One of these traps was an ingenious contrivance made of wire-netting, and was of some size. Having made it we wanted to try it, to see if it would catch rats in reality as well as it did in theory.

Then it was that Monsieur Junod told me about the monster rat in Darkie's bedroom. How he came to know about this rat I do not know, nor did I press him to tell me, but somehow he had learned that Darkie's slumbers were disturbed by a huge rat which had defied the ingenuity of all ordinary traps. So I entrusted him with our latest invention, which was to be placed beneath Darkie's bed, all ready set and baited.

The experiment met with immediate success, for the very first night the giant entered the trap and the cage was brought round to me the next morning containing a regular colossus of a buck rat.

Of course there were several stuffed specimens on show of the common brown rat, but this one I was determined should be something unique, a super-rat in fact. So when I had removed its skin, instead of filling it with the proper amount of cotton-wool, I continued to pack in more and yet more until the skin was so stretched that the rat looked like one of those inflated rubber animals made to support sea bathers. When the skin would hold no more wool, I sewed it up and mounted it. The result was both surprising and alarming.

Towards the close of the rat lecture I used to show different types of trap and explained how each worked and its good or bad points. On this particular occasion I showed them the new big wire trap and began to tell the story of Darkie's rat and the interpreter. The mention of Darkie's name was followed by instant close attention, for she was well known to and admired by most of the audience, and many hopes ran high. Then at the critical moment I took Darkie's monster from its hiding-place and held it aloft for all to behold and marvel at. This was always a very popular crowning touch and never failed to bring the lecture to a pleasant if boisterous conclusion. But by an unfortunate mischance the General had chosen that afternoon and that very time to bring other generals and their staffs to show them over the school, which was a favourite child of his.

At the precise moment when I was holding up Darkie's rat and the hand-clapping and cheering were at their loudest, the General opened the door to allow his guests to have a peep at the Zoology lecture.

The door stood behind me where I could not see it, so that I continued standing with the rat held on high, all unconscious of the other audience in the rear, and it was only when the hilarious laughter suddenly petered out that I turned round to discover the awkward predicament I was in. Generals did not expect frivolity at military lectures.

In spite of this unfortunate occurrence my sojourn at Vieuxbec was a very happy one. I was billeted at the house of the village schoolmaster, Monsieur Berthoud, an old acquaintance, for when we first arrived in France I had been billeted on him at Strazeel and he was now at Vieuxbec. My meals I took with the Town Major, Captain Scrivener, a small, elderly and very precise ex-yeomanry officer. His mess was made up of two very young and enthusiastic signalling lieutenants, who were experimenting with some new piece of magic they referred to as telefunken, a Canadian A.S.C. officer, whose claim to fame arose from his being able to drive the cork out of a whisky bottle by giving it one hard slap with his hand underneath, and Monsieur Junod, the French interpreter. To this select little coterie I was admitted a member.

Captain Scrivener took his duties as Town Major and Area Commandant with commendable seriousness. To the rest of us it appeared to be a pretty trivial task, but according to the Captain the work was heavy and the responsibility grave.

In his habits he was exceedingly regular. Twice a week he rode to Poperinghe to lunch at Skindles. and always returned with the same exciting piece of news. "Fritz was on his last legs," and a special bottle of wine would be uncorked to celebrate these encouraging tidings.

Although I was privileged to share the hospitality of his board for several months, Captain Scrivener and I never became really intimate. He was a man of limited interests. To begin with he stated, while watching me unpack my belongings and place my books on the mantelpiece, that he never read books, or indeed read anything but newspaper articles about horse-racing. As he was not interested in books, nor I in horse-racing, I tried him with another subject, wild birds, and was pleased to learn that birds were a particular passion of his. But on going more deeply into the subject I found that his interest in birds was entirely confined to one species, the pheasant. Not that he had studied pheasants, or ever read a book about pheasants, indeed he proved to know nothing at all about the natural history or habits of his favourite bird. His interest in that noble if half domesticated bird was strictly confined to its wholesale slaughter and artificial propagation for slaughter. To him the English countryside meant a place full of woods and coppices provided by an all-wise deity to harbour vast numbers of pheasants for Scrivener and his city friends to shoot at on Saturdays.

I remarked just now on his regular habits. The Captain maintained it was the duty of a gentleman, and indeed of all of us, to conform as far as the altered circumstances permitted to the routine we had followed at home in peace time. At home, he told us, he always went by train twice a week on Tuesdays and Fridays from Hampshire to lunch at his club in London, and for that reason he made his bi-weekly jaunt to Skindles. But the habit which delighted and impressed all newcomers to the mess was the ritual of the cigarette. Luckily for me I was warned of it in time by the Canadian, or might have done the wrong thing. Naturally the Captain - he was known throughout the district as "the Captain" - sat at the head of the table. In front of him stood a handsome silver cigarette box. After the simple meal was over, the Captain's batman, who he told us had been one of the footmen at home, would open the lid of the box, which was then seen to contain one, and only one, large Turkish cigarette. This the Captain would extract, place it between his lips, his footman-batman then holding a match for him to light it by. The first puff of smoke from the Captain's lips was the signal to the company that they might now light up their "fags," "gaspers" or "yellow-perils."

I was in pretty close proximity to the Captain for over four months, but we had lived in different worlds, and had not one interest or point of view in common. All topics of conversation flagged except horse-racing and the bags of pheasants killed by himself and his wealthy friends. I hope that nothing I have said may be taken to reflect on the good nature of Captain Scrivener; if so, I have done him a grave injustice, for there was no harm in him, but he was just the dullest man I ever met.

At regular and short intervals he would get leave, and I would proudly take over the offices of Town Major of Vieuxbec and Area Commandant. These two posts seemed to me to be sinecures, for the only real 'Work' they ever entailed was the weekly paying of wages to some fifty French and Belgian women who worked at the army laundry. It was a noisy business, with no end of loud conversation, expostulation, argument and laughter. My knowledge of the French language, although improving, was not up to tackling this babel of Flemish and Northern French dialect, I got Monsieur Junod to sit beside .me at the table and help me deal with the problems as they arose. And he was the right man to do it, for he knew just how to treat these women, was stern with some, affable to others, and always had a witty retort to their jokes, some of which, even to my unskilled ears, were of the kind we English, in our honest English way, describe as "very French."

The Town Major's mess-room was divided by folding doors; in one half we took our meals, while the other half was given over to me for my own use, and there I did my rat campaign work, wrote letters and skinned my animals. There was not much privacy about my room, and anybody was liable to walk in at any time to see what I was doing. While I was writing a report one day the Canadian strolled in, had a look round, pointed with his pipe at a photograph which stood on the mantelpiece and said, "Say, doc, is that old guy your dad?" and it was.

As I have recounted elsewhere, I at last succeeded in procuring a beech marten for the collection, and on the same morning sat down to skin it. I had never skinned one of these animals before, and owing to that, or possibly to carelessness, I unfortunately cut through the gland which lies close to the root of the animal's tail. This gland secretes a highly offensive fluid, and in a moment the whole room was filled with a noisome odour of beech marten. Although the smell of one of these animals is not so powerful nor suffocating as that of a skunk - I once had an even worse misadventure with one in the Argentine - it belongs to the same category of foul stenches. On seeing and smelling what had happened, I flew to open the window, in spite of the intense cold, to let the smell escape. All too soon luncheon was announced on the other side of the folding doors, and leaving the marten on the window ledge, I joined my fellow messmates at the table.

We had scarcely sat down when "Phew!" went the Captain. "What a ghastly smell!" Then everybody began to complain of it. To draw away suspicion from myself I said I thought I too could smell a little something. Then one of the alert young signallers, like a fox-hound on the trail, picked up the scent and followed it as it became stronger and stronger and led the pack into my room, where with loud halloos and yoicks they ran to ground my marten, stuffed and set to dry on the window ledge.

Then a truly unholy row took place. Everybody turned on me and said the most ill-natured things about me and about my hobby, ending with an ultimatum that either I promise never again to skin an animal in my room or else leave the mess and go elsewhere.

This beech marten which was the innocent cause of so much disturbance and bad feeling came to me in the following way.

When I found myself once again billeted with Monsieur and Madame Berthoud, I explained to them about the collection of mammals I was making for the British Museum, and asked Monsieur Berthoud if he thought he could obtain for me a specimen of a pole-cat or a beech marten; two animals very similar, which I felt sure must occur in the neighbourhood but neither of which I had as yet seen. Monsieur Berthoud assured me he would do his best to get me over, and the very next day, before his assembled scholars, made a speech in which, after informing his pupils that a very distinguished "savant" was staying in his house, he told them to try to procure a fouin, for which he was authorised to offer, as a reward, the handsome sum of twenty francs.

For two days nothing happened, but on the third the trouble began.

As I lay in my bed that morning I was suddenly awakened by an uproar on the stairs outside my door. The noise grew louder, the bedroom door was flung open, and in marched Monsieur Berthoud at the head of a small but excited crowd, while above his head he held in triumph a dead furry animal.

Having handed over the twenty francs reward and got rid of my visitors, I gave out that another specimen was wanted, but that only ten francs would be given for it.

The result of this was that next morning the same noisy scene took place, when no fewer than three fouins were brought to my bedside, to be followed after breakfast by five more. Seeing things were getting serious, I asked the schoolmaster to inform his charges that on no account would any more rewards be given for further specimens.

This answered on the whole, except when I walked abroad, for often in some by-lane or alley of Vieuxbec a polite child would salute me and call my attention to something wrapped in a cloth or in a basket. On being revealed it always proved to be yet another specimen of Martis fiona.

But not only dead animals came under my notice; there was Albert.

Albert was found one cold winter morning warming himself in an empty tin beside an incinerator at the School of Sanitation. A sanitary corporal, who considered he owed me a debt for some trifling service I had once been privileged to render him, brought Albert to me in the box.

He proved to be a tiny garden shrew found in Western Europe, but not in England, his scientific name being Crocidura russula.

A cage was made for him and a warm hay nest provided. Albert settled down at once, but soon two difficulties became apparent; his vile temper and his voracious appetite.

If we touched his cage he flew from his nest, squeaking and dithering with rage, to see who it was had dared intrude. His appetite was insatiable. Live worms were the only food he would take; and he wanted one every few hours. They had to be alive, as he would only eat one after he had, like St. George, fought and killed the worm. In twenty-four hours he would eat more than his own weight in earthworms, and they were difficult to find in the hard, frozen ground.

Gradually he was weaned from live worms to eat shreds of bully beef, but these had to be held in a pair of forceps, and a sham fight between the bully beef and Albert had to be fought at every meal.

Bob Church, most long-suffering of batmen, took a more than brotherly interest in Albert; indeed he was both a mother and a father to him and would rise several times each night from his warm blankets to take a piece of bully beef and engage in sleepy mock mortal combat with the fierce battling Albert. Thus Albert thrived and, I like to think, showed a sort of fierce beneficence towards his faithful and long- suffering keeper. Everybody loved him, and even the Town Major, no lover of animals except racehorses, grew fond of Albert.

News of Albert in some way reached the London Zoological Society, and I was informed that the Gardens at Regent's Park had never possessed any kind of shrew, as they were considered impossible to keep in confinement owing to their insatiable lust for live worms. But the difficulty was to get Albert to London, as I could find no officer going home on leave who was willing to take a pet that not only bit the hand that fed it, but needed feeding and fighting every hour or two in the twenty-four.

Eventually a special leave on urgent private affairs was "wangled" for Bob, who set off with Albert in his strong box and a tin of the reddest, rawest looking bully beef, for Boulogne. He told my mother, whom he visited with Albert on his way through London, that the journey had been a veritable nightmare, as he disturbed his fellow travellers all the way by his frequent and violent attendance on Albert; but the journey ended well, and Albert found a home in the small mammals' house, and had the honour of haying his photograph in the Field, though the photographer spoilt no fewer than a dozen plates before he finally caught Albert still for the necessary fraction of a second.

I had reason to mention a little way back the name of my good friend Monsieur Junod, the interpreter. Unlike so many French interpreters he spoke and understood the English language. Also he understood women. In fact, what Monsieur Junod did not know about women was hardly worth consideration, while some of the things he did know would not bear repeating.

His official duties at Vieuxbec were to settle all questions as to etiquette, difficulties about billeting, claims by farmers for damage ; in fact, he acted as liaison officer between the civilian population and the British army.

It was his profound knowledge of the workings of the mind of woman which once thwarted an unseemly scandal, one which, if left to follow its natural and military termination, might have brought about a weakening of those sacred bonds which bound the French and English nations together.

To explain this affair I must first describe, very briefly, the conditions which led up to this sad scandal in our hitherto happy and innocent village. Like all other villages in Flanders, Vieuxbec possessed several estaminets, though none was held in higher esteem by the British soldiers than the Réunion des Blanchisseuses. Like other estaminets it was entered by two steps which led down to a well-washed, tiled floor. There were clean-scrubbed tables and chairs for the customers, and a highly polished brazier which burnt all day in the middle of the room. This estaminet was presided over by Madame Henriette Perret - a woman of generous proportions; her age, if one may be so indiscreet, about forty. To assist her she employed two hand-maidens-" Darkie," that big, black-eyed, full-breasted romp of a girl, a great favourite with the British soldiers ; and a fair, delicately pale blonde, Berthe - pretty, and with still a veneer of maidenly modesty which Darkie had lost long ago, if indeed she had ever possessed it.

The customers consisted almost entirely of British troops who were billeted in the village, most of them infantrymen resting "for a spell out of the line, or men attending the School of Sanitation; with a sprinkling of odds and ends-men left in charge of a store or a dump ; some forgotten altogether, as was the case of an elderly and quite inefficient old soldier who was in charge of an incinerator which was never used. A brutal officer one day swooped down on the village and found this old man, and after a short conversation, crudely called him a deserter. This insult the accused indignantly refuted, declaring that when his battalion marched away a year or so ago he was ordered to tidy up the camp and burn the rubbish in his incinerator, and to remain in charge of it until relieved ; and like a true soldier he was carrying out his instructions.

But to get back to Madame Perret of the Reunion des Blanchisseuses. Amongst her most regular customers was a good-looking young soldier, a sanitary corporal. His duties, though scarcely heroic or in any sense spectacular, were of vital importance; and he, having no lust for Teuton blood nor desire for gaudy decoration, was oniy too pleased to go about his humble duties without fuss or fame.

His daily toil finished-a matter of about one hour-it was his custom to spend as much of the remainder of the day as his money or Madame would allow, sitting in her estaminet, sipping "caffy-avec," a mixture of coffee and chicory into which a little cognac has been added, and chatting, and even flirting a little, with Darkie or Berthe.

But, alas! one day the corporal was able to afford more "caffy-avec" than was good or him, and, emboldened or maddened by this poisonous mixture, he did the dreadful thing. At least, he attempted to. He made violent love to Madame. Worse, he paid none of those preliminary attentions, whispered none of those sweet secrets that all women have a right to expect from even the most ardent and passionate of lovers. The corporal so far forgot himself and the respect due to a lady of such dignity and position as to attempt to snatch the fruit without first shaking the bough. Madame's feelings were, naturally, outraged.

The first I heard of the matter, which, of course, stirred the village like an earthquake, was from Monsieur Junod. He came to see me in a state of the greatest excitement and perspiration. His face was red, his looks worried; in his haste to consult me he had for once forgotten to don the orange ribbon which he customarily wore, the Ordre de Ia Minisitere Agricole, on his chest. What was to be done? How to stop a court martial? Military law was most definite as to the punishment to be inflicted on a soldier guilty of this crime against the person of one of our fair unprotected allies.

My own suggestion was that it would be best for him to explain to Madame that the man was drunk at the time, and ask her to excuse him on those grounds. Monsieur Junod was horrified! It would be, he assured me, the worst thing that could possibly be done. This was evidently a case where Monsieur Junod's expert knowledge of women would come in. He had an idea-yes, he saw daylight! He himself would go and talk to Madame, and he believed he could master even so delicate a situation as this one. The next day I met my friend, who was all radiant with smiles and the orange decoration for proficiency in agriculture.

The affair? Oh, yes, he had settled that little business all right. But it had taken time arid tact-much tact. Seated with Madame in her little back room, so lately profaned by the sanitary corporal, the interpreter and she had held converse.

They had talked of many matters; about the Town Major; discussed that difficult question as to why all the English officers in France were bachelors; also the rumour that Australian soldiers would be again billeted in the village soon, which would mean much more money flowing into the till of Madame's estaminet. Slowly, very gradually, the interpreter guided the conversation round to the affair. Poor Madame! what a terrible thing to happen to a woman of her irreproachable character. Monsieur Junod informed her how shocked and pained all her neighbours were, particularly the women (as a matter of fact, he told me the latter were agreed that it served her right, and they were not at all surprised).

Of course, such an insult must be punished. The man must be taught that a Frenchwoman's honour is sacred. And the corporal ; what a pity, too, that so gallant a fellow should die, for, of course, Madame knew the stern, though just, English law for this vile crime was death. He would be tried and then shot at dawn behind the church. Madame asked if some lesser punishment could not be inflicted; for she was really a kind woman and not vindictive. But no; Monsieur had made a close and particular study of English military law, and there was but one punishment. In fact, Monsieur appeared to be also well informed of the family history of the culprit, for he spoke in lowered voice of the corporal's widowed mother in England, so shortly to be childless as well as husbandless. As a matter of crude fact, the corporal, a foundling and a waster from birth, was the child of the Board of Guardians of the Parish of East Ham, which would have been very resigned to their loss had it ever come to their knowledge. Monsieur next became reminiscent. He recalled that gallant affair on the Somme, when the corporal had rushed boldly forward at a very critical situation, bayonet in hand, and killed-he couldn't remember exactly how many Boches, and had afterwards been publicly congratulated and thanked by his Colonel. Madame was interested, for hitherto she thought the corporal had spent his whole military service in the safe and unheroic duties of sanitation-which, indeed, he had. Madame's face began to show a less stern expression, though she was still inclined to let the law take its course.

This was the moment when Monsieur Junod's inside knowledge of women came in. Exactly what he said or how he said it, I do not know. The pith of his argument was this:

Regrettable as, of course, the whole affair was, there was this to be said for the corporal's good taste. Madame herself was famous for her good looks, and who could blame a young, a gallant, and a brave young man for falling violently in love with her? Some men, lees particular, might have taken a fancy for Darkie, that bold hussy who tried all she could to attract the men, or that quiet, sly puss, Berthe. But no, the corporal took no notice of those two younger women, and had fallen in love with Madame. Monsieur who seemed to know everything, was able to tell Madame in strict confidence how the corporal had confided to him that for many months-in fact, since he first saw her-he had been in love with the beautiful proprietress of the Estaminet de Re' union des Blanchisseuses, and how this smouldermg passion had, alas, suddenly overwhelmed his reason, with the dreadful result that the podr fellow, so brave, such a boy, must die a scoundrel's death.

But die he must, and rightly too. Madame's honour must be vindicated.

But all ended happily. Madame was generous, the corporal forgiven, and Monsieur's profound knowledge of women was recognised and acclaimed by all.

A few weeks afterwards the Town Major signed the necessary forms, allotting a certain room as a billet, in an estaminet called la Re'union des Blanchisseuses, to a certain corporal (sanitary duties), the proprietor having no objection to the arrangement.

The whole of my time at Vieuxbec was not taken up with lectures at the School of Sanitation, going for country rambles, skinning animals or gossiping with Monsieur Junod. As G.O.C. Rats, Second Army, there was enough and more than enough to occupy my days. Almost every unit in the whole Army area had to be visited, infantry, artillery, engineers, ammunition parks, transport lines, etcetera, as well as all the Field Ambulances. Commanding officers had to be interviewed and given instructions how the rat traps were to be used when, if ever, they were issued. All this while I was designing and experimenting with new types of trap. Any feeling of indifference or hostility there may have been at first to the scheme was compensated by the interest and encouragement I was getting from England, which was soon explained when I heard from my father what he had been doing.

At this period one of his best friends and his almost daily companion was Lord Haldane, who always lent a sympathetic ear to my father's news about me and what I was doing, and he heard all about the rat campaign. Apparently Lord Haldane had once written a letter about me and my rats to his friend, Sir Alfred Keogh, the Director General of the Army Medical Service, who approved so much of the scheme that he forwarded the letter, with a covering one of his own, to Lord Kitchener. What happened after that I do not know, but it was not surprising if my work later came to be regarded in a more serious light and that I was granted almost every facility I asked for.

It was about this time that the authorities were becoming alarmed by the spread of mange among the horses, due to a parasite, one of the sarcoptes. This very contagious disease was spreading from one horse-line to another and brought the condition of the horses to a very low ebb. To prevent this, measures were taken to isolate all infected stables or horse-lines, and all infected horses were treated by being dipped in tanks of strong chemical solutions, but still the disease extended.

- left : rat-proof bed

- right : skinning a rat

Part of my work at this time was to examine large numbers of dead rats, and I noticed that some of these were mangy, and it naturally occurred to me that rats might very easily be acting as carriers of the disease, by passing from one stable to another, and so infecting horses, straw or fodder. As this matter was one entirely to do with the veterinary corps and nothing to do with the medical branch, I was anxious to make quite sure my hypothesis was sound before reporting it. Unfortunately I confided my suspicions to a pushing little R.M.C. staff major (not a regular) who, thinking he saw in it something which might bring kudos to himself, behind my back and without my knowledge, wrote a hurried report and rushed with it to a Director of the Army Veterinary Service, who, disliking the man and resenting his interference, refused to discuss the matter with him and showed him the door.

Owing to this self-seeking and tactless busybody I had to go very quietly with my further experiments.

As my father took such a keen interest in all I was doing I told him in a letter my theory that rats infected horses with mange, though nothing about the interfering major. The result was that my father spoke about it to Sir Ray Lankester, who was at once interested and suggested I should make microscopical examinations of the sarcoptes of the rat and the horse, not only to settle the question whether horses contracted mange from rats, but to ascertain whether the sarcoptes contained the bacillus of a rare disease which was then beginning to infect the troops - spirochtosis icterohamorrhagica, an infective jaundice recently discovered in Japan and believed to be spread by rats. If this could be proved, he said I would have made an important discovery. At this time I had no microscope nor any means for carrying out research work, but owing to the efforts of Sir Ray Lankester and Sir Walter Morley Fletcher, the Secretary to the Medical Research Council, I was in due time given the use of a laboratory near Poperinghe. My father, although no man of science and certainly no catcher of rats, left no stone unturned to help me in my project.

Amongst other experiments I was anxious to try, was the effect of different scents in attracting rats to traps. After some trouble - managed to procure and send me small quantities of various essential oils, as cloves, aniseed and caraway seed. But there was another scent I wanted to try, which I had heard was used by trappers in the North of Canada, called oil of rhodium. For many weeks my father tried to get me some of this with no success. He wrote to me that he was told there was not a drop to be procured in London for love or money. During his inquiries he had learned that this oil was made from the root of a convolvulus which only grew in the Canary Islands and that each year the whole crop was sold to a merchant at Leipzig. After trying everywhere he at last applied to the firm of Messrs. Rubeck, the largest merchants of such oils in the city, and on March 23rd he wrote to me:

"I have succeeded in getting you a bottle of rhodium I hope you will congratulate me. It is believed to be the wily specimen of oil of rhodium left in the City of London."

This winter had been a very cold one, the whole country was iron-bound for weeks, but at last as the days became longer they became warmer, and the belated but longed for spring arrived; and with it the beloved birds.

Every few days I had to go to Abeel to discuss matters with the D.D.M.S. of the X Corps. I used to go there on foot, walking the three miles through the meadows along the banks of a winding brook. I am afraid I wasted a lot of time doing so, for there were many distractions by the way.

In the winter I would often flush a woodcock or a wisp of snipe, and once for ten minutes I watched a water-rail skulking along the banks of the stream. By February a few wagtails, the white and the pied, were to be seen and flocks of one hundred or more lapwings. By the middle of March the birds were singing, blackbirds, song thrushes, yellow hammers, meadow pipits and larks, the crested as well as the skylark.

One fine day my friend Junod and I went to explore the wooded sides of Mont des Cats. There were not many birds to be seen, but we had a wonderful view, through our glasses, of a small flock of hawlinches sunning themselves on the top of a bare oak tree. We saw also a pair of tree sparrows, such gentle-men in comparison to their vulgar cousins of the house top, and listened to the delightful clear trilling of a cirl bunting.

It was only a few days before my mother's birthday, and I managed to buy her a present at the monastery which stands-or stood-on the summit of the mount. She had a great fondness for cheese, liked nothing better than to sample a new kind, and was always discovering new cheeses. Whenever I was able I got her a novelty. The rarest I ever gave her was a goat's milk cheese I obtained in Formentera, the smallest inhabited island of the Balearic group. I am sure it was the first of its kind that had ever been exported to England, and for more than one good reason. All across Spain and France and Kent the prize had to travel suspended by a string outside the railway carriage window. My mother was very nice about that cheese, but I think it appealed more to her as a collector of rarities than by its delicacy of flavour.

The Mont des Cats cheese was one of much less potency than that of Formentera, being more like a cream cheese, and passed the base censor quite successfully.

Whenever I heard that the 69th Field Ambulance was in the neighbourhood, I used to ride over to see them. My only other social visits were to a very friendly squadron of yeomanry, the. North Irish Horse, who were acting as Corps Cavalry, and who. had a mess at Vieuxbec. I often spent the evenings with them playing a simple game they taught me called Blind Hookey or Uncle Sam. This is one of those games which appears so guileless and in which even the worst duffer at card games can join at once and be fleeced, and is, I believe, the one employed by the villain in melodramas to ruin the honest village lad.

One evening when it was decided to stop playing, one more round was proposed and agreed to, and a special prize offered. In one corner of the room stood a deal box in which the squadron fox-terrier bitch was at that very moment in the throes of labour. The prize was to be one of the puppies, the winner to make his own choice. Perhaps because I had lost consistently the whole evening, perhaps because I did not want a dog, the cards turned all in my favour. Just as the last card was played and I had been proclaimed winner, the regimental M.O. who was in attendance on the little bitch, informed the company that the interesting event had come to a happy conclusion, and we inspected the litter of four.

They were an odd lot of puppies, no two appearing to belong to the same breed. This curious fact the doctor explained by telling us that during the period of her courting the squadron had moved from place to place, never remaining more than one day at any.

After very carefully inspecting the litter, I chose the newborn puppy which looked to me most like a fox- terrier. As soon as ever it could be weaned, Bob Church brought it to my billet and undertook the duties of a wet nurse, and henceforward Jim became a member of the family. He went through all the fascinating but all too short stages of puppyhood, and eventually turned out a very nice, smart little fox- terrier and took a very keen and practical interest in the rat campaign.

Amongst other friends I made at Vieuxbec was the local poacher. We first met one day in a little wood. I wondered what he was doing there, and I expect he must have wondered what brought an English officer there. Like so many poachers he was a grave man, with courtly manners and a profound know-ledge of the habits of wild animals. When I got to know him well, after some time and francs spent in a small auberge, I asked him if he could get me a rabbit. This may seem a modest request, but these animals, which used to swarm over Flanders over two years seen one, nor been able to get a specimen for my collection.

Before long my friend the poacher caught me a rabbit, as well as a pole cat, and several black rats.

It was he who took me to see a cock-fight one Sunday afternoon. I had never seen one before and have no desire to see another. The mains took place on the ground, in a ring formed by onlooking Flemish farmers and a few British soldiers. There was a lot of betting in small sums over each one, but it was a brutal sight to see such handsome, gallant birds stabbing at each other with the long sharp steel spurs which were strapped to their legs.

Spring seemed as if it would never come. In the early days of April blizzards still continued and deep drifts of snow lay beside the hedges. The most conspicuous birds were the magpies, which roamed about in robber bands of thirty and forty, and all too many jays.

On April 9th I heard the first spring migrant, a chiff-chaff, who had come in spite of the cold. Four days later, on one of my official walks to Abeel, I found a nest of a song thrush in which were four eggs. Chiff- chaffs were becoming more numerous every day, in spite of the gales and occasional snow storms. On the 19th the first swallows appeared in the village street, when two flew up and down outside the mess and I heard the first willow wren, so spring had really come at last. From now onwards the weather improved and each day brought its new arrivals and its new joy.

Redstarts, grey wagtails, tree-pipits, and at last a cuckoo came. The last day of April was a red-letter day. It was the first day of really hot sunshine, and I decided to visit the D.D.M.S. at Abeel.

The first newcomer I met was a whinchat, gladly singing its trilling song, a mixture of harsh and clear notes. Its song brought back memories of Iviza, in the Balearic Islands, which is full of singing whinchats in the spring. During that short walk I must have seen forty whinchats which had probably come in a rush the night before. There were other new migrants as well, a lesser whitethroat and several common whitethroats and cuckoos, which were calling one to another, and easily seen, for there was still not a leaf on the trees to hide them.

In the little stream I flushed a water-rail and a green-shank. As though this banquet of birds was not excuse enough to delay me, there was more to come. As I happened to be lying face downwards on the bank of the rivulet I noticed a small dark object swim rapidly downstream, under water, and wondered whatever it could be. I kept perfectly still, no thoughts of an impatient D.D.M.S. disturbed me, and presently I was rewarded. The dark submerged object was returning rapidly upstream, and when only a couple of feet from my eyes it emerged on a tiny shingle beach, shook itself like a retriever dog, and turned out to be a very handsome water shrew, dressed all in black velvet, and looking as dry as if it had never been in the water at all.

When at last I got to Abeel I apologised to the D.D.M.S. for having been unavoidably detained, but did not bother him with details as to what had made me late.

What a day that was. On my way back to Vieuxbec I saw two blue-headed wagtails, which were so tame they allowed me to watch and admire them within a few feet. When at last I reached the village that evening, there was yet one more treat in store, for several swifts had arrived during my absence, and were flying up and down the street.

This memorable day with birds was to be the last for some time. Next morning a telegram came from General Porter, the D.M.S., to go and see him at Hazebrouck at one o'clock. He was most friendly and after lunch showed me a most flattering letter from Sir Walter Fletcher, to say that anything I needed in the way of scientific instruments or apparatus would be supplied by the Medical Research Council.

The General also told me another welcome piece of news, that at last the first consignment of rat traps, the sort I had asked for, had arrived, and that I could set about their distribution at once.

Things now began to move with rapidity. The very next day the General came to Vieuxbec with Colonel Stephens, of the Medical Research Council, and after a talk told me he was arranging for me to go to the iota Casualty Clearing Station at Remy Siding, just outside Poperinghe, to work in a Mobile Laboratory there with the late Adrian Stokes, the bacteriologist.

In the meanwhile I was kept busy from morning to night, allotting the traps to various units and instructing the officers and N.C.O.'s who were to be responsible for them, and who were to supervise the setting of them. It was, of course, a pity the traps had not been procurable and issued at the beginning of the year. Every rat which ought to have been caught in January and February would now be father or mother of one or more families. But all the same, a great improvement had already followed the orders I had initiated for food protection. Every food store was now protected by wire-netting, and in many places where rats used to swarm, scarcely one was to be found.

a hand-colored illustration from a French magazine - 'le Pélérin'