- 'Hoodwinking the Germans'

- By Lt. Anselm Marchal

Giving the Enemy the Slip

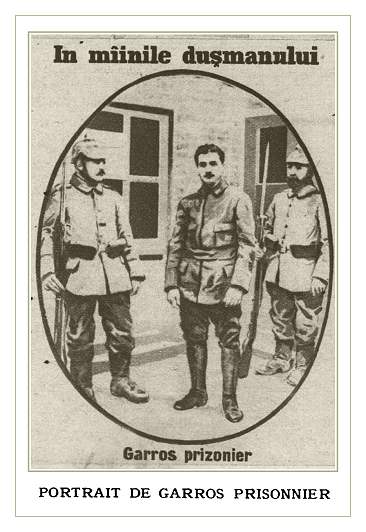

- left : a reproduction of a heavily retouched photo in a Roumanian magazine

- right : Roland Garros as prisoner - photo from 'Illustrirte Zeitung'

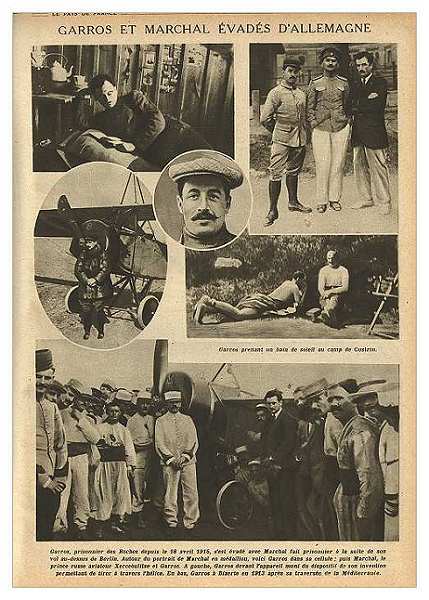

- left : from a French newsmagazine ('Le Pays de France') 'Garros and Marchal Escape from Germany'

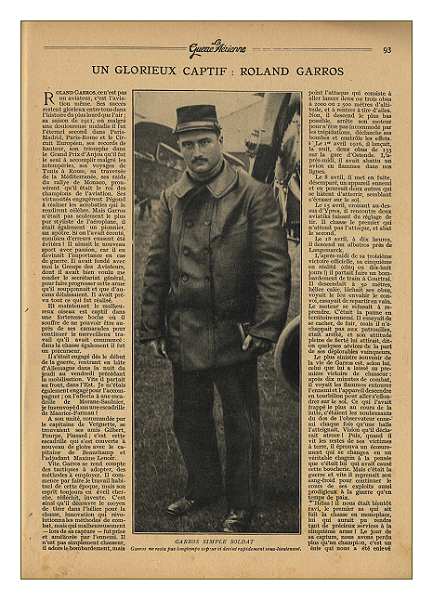

- right : from a French magazine 'la Guerre Aerienne'

After my release from the civilian prison of Magdeburg, I was sent back to Scharnhorst, the most rigorous prison camp in Germany. A little later, towards the end of December, 1917, a new companion in captivity was given, or rather returned, to me. It was Roland Garros.

He and I had been imprisoned together before, but separated because we had refused to answer the incessant roll-calls with which we were plagued and had incited the rest of the prisoners to do the same. Garros had been confined in the camp of Burg, but now all French officers were being evacuated from Burg in order to make room for the Russian officers who were being concentrated there. Germany and Russia were making the peace of Brest-Litovsk, so it had been decided to prevent any contact between our wavering allies and ourselves.

After Burg, Garros was at first transferred to the Wagenhaus with the French officers who were not undergoing reprisals. He was kept there for about two weeks. At the end of that time a search proved him to be the possessor of the important sum of two marks in German money and a pair of pincers. It needed no more to earn him a few days' confinement in the cells. Afterwards, as penance for his two crimes, he was sent to Scharnhorst.

I found in Garros the good friend of peace-times, who had always had my affection, and the great pilot of war-times, who had as yet been prevented by circumstances from giving his full measure.

The close intimacy in which we lived at Scharnhorst and the trials we were soon to undergo together could not do otherwise than transform our former good-comradeship into the deepest of affections. Nobody could be admitted to the intimacy of Garros's mind without feeling respect and admiration for his very superior intelligence, nor into the intimacy of his heart without loving him.

As soon as we found ourselves together again at Scharnhorst, we "pooled" all the different projects or escape that he and I had imagined. Garros had only one idea-to escape and take his revenge. Before six weeks were out we had found a possible way of getting out of the camp.

When I first came to Scharnhorst I talked freely of my intention to escape. One day a Russian officer came to me with a most engaging air, saying how much he deplored the lack of success of my previous attempt, and offering to help me in a new effort, all this being seasoned with so many compliments on my coolness and courage as to put me well on my guard. Finally, he bluntly offered to take me to a room of which he had the key, and from which he assured me I could escape into the moat without being seen.

While I had few illusions as to the sincerity of this most devoted of Russians, I took him at his word and let him show me the little room he had described. Once there I had only to put an eye to the window to assure myself that it would be impossible to find a less promising place. At ten metres distance was silhouetted the grey form of a sentinel, and as he would undoubtedly be given very good reasons for being on his guard, it is easy to imagine what would have been the fate of Marchal the runaway potted at "sitting." My Russian was, as you choose a most extraordinary imbecile or something of a dirty dog; for myself, I lean towards the second hypothesis.

After that I was more discreet, in case some other amateur Judas should try to betray me; but my constant preoccupation was how to part company with my guardians, and I did not stop examining every possible plan of escape.

Escape in the twilight, by boldly walking through one of the gates, past the sentries, still seemed to me to be the method requiring the greatest amount of assurance, but at the same time offering the greatest chance of success, as being the least expected.

Since my previous attempt I had been particularly recommended to the vigilance of the non- commissioned officers of the guard, and confronted with each one in turn, so that in future they would have no difficulty in recognising me, whatever my disguise. I had to get over this difficulty. Ever since the beginning of the winter I had never shown myself in the courtyard except wrapped up in my overcoat, the collar turned up so as to hide almost the whole of my face. As the months passed I hoped that the guard would have forgotten my face, and any way my face would have become blurred in the memories of the non-coms. Garros agreed with me that this was the best plan, and we prepared accordingly.

We would both dress up as German officers and walk boldly out of the prison.

The first thing was to fake the kits. We begged some permanganate of potash from a doctor and made a, strong solution. In this we washed our two French officers coats, until they ceased to be horizon blue and became campaign grey. The buttons we carved out of wood with penknives, and painted them greenish bronze. Out of our pilots' overalls we got enough fur to make collars for the coats.

One of our friends made us caps. They were a great success. He made the frames out of pieces of cardboard from a box. The tops he covered with blue cloth cut out of a pair of trousers, and then made bands out of a red-flannel belt. This he stole from an old colonel who wore it at night. We hoped the poor old man would not catch a chill. With some nickel he made cockades such as the Germans carried on their caps; and no one at a distance, or in a bad light, could have told them from the real thing. They were "creations."

We cut down some slats of wood into the shape of sabres and blacked them over with shoe-blacking.

Garros produced two suits of civilian clothes. Goodness knows how he had kept them concealed in his trips from prison to prison. He had, however, brought them to Scharnhorst and secreted them between a wall and a wood fence where there was a loose plank. The Germans never knew where those civilian suits came from, and I cannot tell. I don't know.

The hardest task was to forge false passes with false names. I knew German and Germany well, for I had lived there and travelled in the country before the war, and I managed these pretty successfully after several tries.

As the date we had chosen arrived we got the assistance of our comrades. There were none of the "amateur Judases" among them. They worked for us like blacks, and they gave us all their assistance loyally. Two other officers-Captain Meyer and Lieutenant Gille-also determined to escape, but were prepared to let us get away first.

It was important to keep our escape concealed as long as possible, so as to give us a good start. We intended to go as dusk came, so the evening roll-call was the first problem. We devised a complicated plan.

Garros and I were in Room 7 in the right wing of the Scharnhorst on the first floor. A wooden partition that divided the casement in two separated us from Room 8. A trap-door had been made in this partition, by means of which two of our comrades from No.8 proposed to pass at the opportune moment and replace us in No.7. But on reflection our friends decided that the proximity of the two rooms would not allow the substitution, however rapidly carried out, to be made in the too-short time that it would take the inspecting officer of the week to reach the second room after having assured himself that the first had its full number of occupants. So it was decided to ask two French officers of Room 11, also situated on the first floor, but in the left wing of the bastion, to come and occupy Garro's and my beds when the non-commissioned officer of the week had visited their room and had been able to announce to his lieutenant "Alles da!" ("Everything there").

This time, in order that no absences should be remarked from Room II, it was essential that our two substitutes should be found in it when the officer came, condemned though they were to spend the whole night in No.7. They were found there, if not in person, at least in the shape of two friends from Room 15 on the second floor, which was situated immediately over theirs. Lieutenant Chalon, our renowned engineer in the Scharnhorst, cut a hole through the solid masonry of Room 15 down into Room I I and concealed it. As soon as we were gone our two friends from No. I I would come to No.7 and get into our beds. The two from No. 15 on the second floor would drop through the hole in the floors and take the place of the two who should have been in No.11. As soon as the German officer had inspected No. 11I and started up the staircase to the second floor they were to be hoisted up again into their own room by main force, so that by the time the Prussian officer and his N.C.O.'s had got to their room they would be back in their own places and the Prussians could report "Everything there."

The falsification of the morning roll-call, however, would not be so easy, for it was held in the open courtyard. The inmates of each room were fallen in as a group and counted, while the rooms were guarded by sentries, so that no one could go in or out.

The day arrived-the I4th February, 1918. Two of our friends kept watch in the passage, to see that we were not disturbed. Several others came to help us with our kit. We rigged ourselves out in our civilian suits and put our faked German overcoats over them. To cover our trousers legs we had some gaiters. Then we strapped on our "swords," adjusted our caps to a good angle with a touch of swagger, and as complete German officers were ready.

As it began to get to twilight we marched out and up to the gate known as the Wagenhaus Gate.

We were a little behind our schedule and the twilight had already turned to darkness. Garro's watch - I no longer had one - marked ten minutes to six, and the train we wanted to catch left Magdeburg at half-past six. There was no time to be lost, and we lost none.

Approaching the first sentry I put on my most impressive voice and roared at Garros that it was insufferable that a German colonel should be whistled after and hooted at by the prisoners, and that it was our duty to go immediately to the general and ask him to take energetic measures to bring those insolent Frenchmen back in to the paths of virtue.

The first sentry heard my words very plainly. His attitude was proof enough of that. Without uttering a syllable he drew aside, and stood at attention.

We arrived before the second. He asked us, in a timid voice, some question that I did not catch. Was it a password he wanted? If such a word existed, it would be the only one that we were quite incapable of uttering. I made good anything that may have been lacking in our reply by the crescendo in which I continued my fierce invectives against the disgraceful Franzosen who were making the life of the camp commandant a misery to him. It was time that a stop was put to such a monstrous state of affairs. Garros agreed energetically by a sort of hoarse growling. Our tactics were successful. The sentry opened the great gates and let us through.

A little farther along another sentry guarded the barbed-wire barrier that had been laid across the slope leading up to the gates. But this third guard considered himself to be covered by the second, and he said nothing to us. He stood to attention, and then saluted and opened the barrier for us.

We had now reached the foot-bridge over the moat. Before it was a sentry, who demanded to see our passes. Although we had them in our pockets we preferred not to show them unless it was absolutely necessary. In my most terrible voice I roared an emphatic, "Mind your own affairs!" at him, and added, "That makes the third time we've been asked for those damned papers !" and we brushed past, and he made no further attempt to stop us.

We walked in step slowly across that bridge, and even more slowly into the darkness beyond it, our hearts in our mouths, expecting at any minute to hear some pursuit, some of the sentries or the guard after us.

As soon as we judged we were clear and out of sight we hurried to the edge of a railway track, and in a broad ditch we crouched while we tore off our overcoats, our leggings, the officers' caps, our wooden swords, and, hiding them in a drain, we turned into peaceful German citizens. Garros had a soft felt hat and I a most disreputable cloth cap. Sticking these on our heads, we made back to the road and walked with the utmost nonchalance to Magdeburg and into the railway station.

We hoped that we had a good start. Later we heard that everything had worked well. The German officer inspecting at the evening roll-call had not noticed our absence, though our two friends from No.15 had only been hauled back up from No.11 just in time. Though out of breath and covered with dust they bamboozled the guards successfully.

The morning roll-call had also been successful. Garros's absence was missed. A friend from our room put on his pilot's leather coat, turned the fur collar up to his eyes as was Garros's habit, and took his place in the ranks. The "dancing master" on duty that day was superbly oblivious to this masquerade; but not seeing me in the group, and hearing that I had reported sick, he sent up to No.7 the non-com. Especially detailed to watch me.

The man-who was known to us as Bismarck came into the room, where he found only one officer, whose head and shoulders he was unable to see, their owner being busily occupied in searching for some unknown object under my bed. Without changing his position the officer in question addressed a few words of German to Bismarck, which sufficed to reassure him, as I was the only occupant of No.7 able to speak to him in his own language.

The officer who pretended to be myself was Lieutenant Buel, who knew a little German. How he found a substitute for himself and bluffed Bismarck and the sentries I don't know. It is a mystery I have never been able to fathom, for if any prisoner for any reason did not fall in on morning roll-call his room was specially guarded by a sentry, with strict orders to see that no one went in or out.

None the less, the result was that we got a good twenty-four hours' start, and it was not until the following evening roll-call that the Germans spotted that we were gone.

When they did find out there was a real blow-up. The German papers demanded that the Chancellor make new arrangements so that no other prisoners should get away. The commandant of the camp was dismissed in disgrace. We, none of us, had any sympathy with him in that. Then a whole army of Berlin secret police descended on the prison and investigated everything and everybody, but could not for the life of them find out how we had got away.

Those in themselves were good enough results, but they were not the best. The Berlin secret police officers, the ersatz Sherlock Holmes, not only had their trouble for nothing in so far as finding the smallest clue as to bow our own escape had been managed, but they facilitated, most certainly against their will - the successful accomplishment of another. Absorbed as they were in ransacking the rooms and searching our fellow-prisoners they neglected to keep watch over their own pockets. And the result was that Captain Meyer, who had given up to us his turn of escape, rendered to one of the detectives the sincere flattery of imitation - though he carried out his investigations more discretely than did the German, for he relieved him of all his identity papers.

Two days later, with Lieutenant Gille, Meyer marched out of the prison. At the gates he presented the papers of the secret service officer. The doors and barred gates of the Wagenhaus opened before him and he was gone.

Staggering at this escape right under their noses, while they were in charge and investigating, the Berlin sleuth-hounds had to set out on a new inquiry and even then found nothing, for I expect the "tec" didn't let on that he'd had his pocket picked.

Meanwhile, while the officers of four different rooms were managing, with such ingenuity, to hide our absence from Scharnhorst for a night and a morning, we were going full-steam ahead towards the north- west.

Several times we were treated as if suspicious characters. Once several peasants who were travelling in the same direction kept asking us questions of all sorts. It may just have been their native curiosity. In order to appease this curiosity, I told them that we were going to Brunswick to install some motors for the Swiss Company, Oerlikon. They swallowed the story and left us in peace, and we accomplished the first day's journey without further incident.

The train deposited us in the evening at Brunswick, and that which was to carry us towards Cologne would not pass for another six hours. What to do in the meantime? We decided to kill time by walking. We started, but into the town. The night was very dark, cold and dry. We followed a sleeping street bordered by a high fence, on the other side of which was a cemetery. If only we could get into that we would be certain of finding the safest of resting-places. The opportunity was presented to us before very long; we found a loose paling, and managed to squeeze through the narrow opening.

Our only impression, in the midst of tombs surrounded by trees black and sombre in the night, was one of security - security such as only a cemetery could possibly procure for individuals in our position. A little alley led us away from the street, and, sitting down on a tomb, we began to talk in whispers.

Hours passed. It was midnight. Suddenly I felt Garros's hand grip my arm.

“Listen," he whispered, and we both strained our ears. It was an eerie sound that we heard, indefinable, a sort of rustling, coming from where we did not know, caused by what we did not know. It seemed to draw closer-but no, it receded, stopped, and then we heard it again, approaching. It may have been only the dragging steps of some guardian making his rounds, but even that earthly explanation was not too reassuring, and the sound was not at all like that of footsteps. Whatever it was, we did not like it, and with one accord we took to our heels. I do not doubt that in our undignified flight we trampled more than one flower-border, stumbled over more than one grave, tore down more than one wreath; but at last we reached the gap in the palisade and in an instant found ourselves out in the street, where no strange thing moved about.

Train time was approaching, and we went back to the station. In the second-class carriage where chance more than our own desire led us we found two officers occupying the corners on the corridor. Never was there so undesirable a meeting; yet to turn about and leave them would have been of the utmost imprudence. We were in the soup, and the best thing we could do for the moment was to stay in it. Passing before our uncomfortable travelling companions we gave them the politest of Guten Abends. They replied with a nod of the head.

Squeezed into the two other corners, we sat and waited for the train to pull out. The four or five minutes we had to wait seemed an eternity. Anybody in our position is invariably afflicted by the constant and painful impression that a policeman is following on his trail, scenting the escaped prisoner from afar. At Brunswick we suffered again that agonising sensation. Whoever was the individual who walked steadily up and down the platform, keeping close to our compartment and apparently never for a minute quitting it with his eye, he can flatter himself on having made us pass a most unpleasant moment....

At last the train drew quietly out. The night passed without incident, and in the morning we found ourselves at Cologne.

Feeling somewhat ashamed of my cap, I bought a hat, and then we wandered idly about the town. But in spite of the crowded streets that made it highly improbable that anybody would pay any attention to us, we were still harassed by the fear of spies. The most reassuring manner of passing the morning that we could think of was to spend it in the cathedral; we would hardly be looked for there. We went, and heard three Masses, one after the other in rapid succession.

At a certain moment my companion nudged me with his elbow. He drew my attention to two other civilians whom we had already noticed at the preceding mass, and who now seemed to have every intention of hearing the next, like ourselves. After examining them carefully out of the corner of our eyes, we felt reassured. They were probably only very pious folk, unless, like ourselves, they had taken refuge in the cathedral in order to avoid undesirable encounters.

Prudence bade us not to venture into a restaurant, so for lunch we ate some chocolate without bread, and washed it down with beer in a bar. Afterwards we bought an electric torch that we would need for our future nocturnal peregrinations. Then we sought in the darkness of a cinema the relative security that we had found in the morning under the lofty and cold roof of the cathedral.

At the fall of evening we took a workmen's train for Aix-la-Chapelle. It was crowded. The intermediary stations being as numerous as in the outskirts of Paris, the halts were very frequent. As we drew into one of them some one in our compartment cried out: "Ah, there are the police again, watching all the exits of the station. . . . I wonder what it means?"

Naturally, the meaning to us was that we had been tracked and it was for our benefit that the police had been mobilised. By a coincidence that we judged to be most fortunate the train slowed down at that moment. T he stop-signal was down. I whispered to Garros, " Let's take the chance!" I opened the carriage door, and a German soldier who was standing by it said, "What are you up to?"

"Don't you worry about that," I said; "we are already an hour late, and we don't want to miss the last tram."

While I was talking Garros had jumped from the train. I followed him, and the soldier closed the carriage door behind me.

We found ourselves in the open country, close to the railway embankment. As we were not certain of the direction of Aix, we decided to steer north-west. We walked on until we reached a spot where the houses, that had been widely scattered, began to group themselves in successive and well-populated agglomerations. Obviously, the outskirts of a big town.

We knew that one of the characteristics of Aix-la-Chapelle was a wide exterior boulevard, lined with trees, and at about eight o'clock we came out on a boulevard that answered that description.

We had a map annotated, and which we had smuggled through to us in the prison. This told us that we should turn to the right, down a street that because of the unevenness of the ground presented the peculiarity of having one pavement raised up by four steps. The boulevard led us to that street, which we entered and followed. On a signpost we were able to read " Direction de Tivoli." We were on the right track, so, quite sure of ourselves now, we continued along the street, which rapidly became suburban in character. We had penetrated on to the territory of Aix, but not for more than ten minutes.

Once more in the open country, we directed our course by map and compass. The compass, too, had been smuggled into the prison in a parcel of food. The weather was chilly, but dry and seasonable-far from the fifteen and twenty degrees of frost from which I had suffered so cruelly during my first terrible journey in trying to escape.

Keeping off the roads as much as possible, jumping the little rivers in order to avoid having to show our passports at the bridges, throwing ourselves flat on the ground at the least alarm, we had yet managed to make some thirteen or fourteen kilo-metres by two o'clock in the morning. We calculated that only two more kilometres, at the most, still separated us from the frontier.

We entered a wood. The dried leaves with which the ground was covered made a continual crackiing noise under our feet which, it seemed to us, must be audible at a great distance. Fearing that it might betray us, and looking for a path on which our footsteps would make less noise, we flashed our lamp along the ground. Immediately a shrill whistle rang out. It seemed to emanate from a little cabin that we could see on a height above the woods.

Undoubtedly our light had been seen. If that cabin should prove to be a guard-house filled with soldiers set there to watch the passages over the frontier we would be pursued and perhaps caught-and taken back to Magdeburg. No! We had no intention of accepting that. Turning to the right, and without quitting the copse, we took to our heels.

After a few minutes we came out on a transversal road, which, we realised, would lead us back in the direction of Aix. But we had no choice. Above all, we must get out of that patrol-and sentry-infested zone. A prey to nervous apprehensions that the high stakes for which we were playing may render excusable, we felt that an enemy lurked in every shadow, ready to leap out on us. At one time we heard footsteps both behind and before us. Turning again to the left, we fled across the open fields. Ditches and unseen obstacles made traps for us in the dark. Garros tore his face and I my hands in climbing over artificial thorn hedges of barbed wire.

The alarming noises continued. Suspicious lights, quickly flashed on and off, showed here and there in the distance. All those noises and lights were not necessarily a menace to us - we knew that quite well, but were incapable of distinguishing the innocuous from the dangerous. This perhaps needs some explanation, and it is this.

In that frontier region between Germany and Holland smuggling was never at a standstill. The smugglers made signals to each other by whistling, modulating their voices to imitate the cries of all kinds of birds. somewhat after the fashion of the "Pirates of Savannah," an old melodrama of my childhood's days.

Optical signals were also used. Thus, in the fields, we often saw certain individuals who followed along the railroad track, bent double under heavy loads, and who from time to time, in order to warn the others, gave short flashes of light with their electric torches. We said to ourselves that perhaps back there in the woods it was only with maltouziers of this kind that we had had dealings, and whose whistling was no more than an answer to what they mistook for the signal of one of their acolytes. But hardly had we conceived that comforting thought than other shadows appeared, going in the same direction along the railway track; and this time there was no doubt about it. The silhouettes were those of soldiers on patrol. The business was comic enough to watch, had it not proved to us that we ran the double risk of being pursued on sight, either as escaped prisoners or as smugglers; and once captured, there would be little choice between the two; the result for us would be the same.

In any case we were doomed to postpone our attempt to cross the frontier until the next night; and the only thing to do in the meantime was to return to Aix-la-Chapelle. We must in any case be fairly close to it, as we had been walking for three hours and must easily have covered on the return road the thirteen or fourteen kilometres that we had previously made in the opposite direction.

Going straight in front of us, we came to a high railway embankment under which passed the road we were following. The spot was guarded by a sentry. Like all his kind, he was provided with an electric torch, the light of which he turned full on our faces.

"Have you got your papers?"

Without any previous collaboration the same idea came simultaneously to both of us. We put on the voices and the gestures of extreme intoxication. I replied to the soldier.

“Ole man, now you jus' lissen to me. . . . You can't 'rrest us jus' because we live at Aix. . . . Got paid to- day, we did. .Hada rousing ole beano with some of the chaps. . “

“Where ?”

I gave the name of a village on the outskirts of Aix, and launched out into a complicated but circumstantial description of our bacchic prowess. The sentry showed himself indulgent. He clapped us on the back in friendly fashion, and, " Get along with you," he said. "Pass, but don't let me catch you around here again."

To which I answered with the profoundest conviction, "You can count on that, ole man."

When we reached Aix-la-Chapelle it was nearly five o'clock in the morning. In the street we came across a night-watchman whose business it was to see that all doors were properly closed. I went up to him and said: "We are strangers in town. Could you tell us of an hotel?"

Doing better than merely tell us of one, he led us to it.

We had to register-using of necessity false names-and indicate the identity papers that we would be able to produce, and the information we gave on that second point was exactly the same value that we had given on the first, and we had to pay in advance, having no baggage of any kind.

The red marks that Garros had on his face from his fall in the barbed wire earned for him more than one suspicious glance, from which I also suffered by ricochet, thanks to my lacerated hands. Nevertheless, we were allowed to have our two beds, of which we stood in considerable need, after our nocturnal stroll of twenty-five or thirty kilometres. How-ever, we did not linger over-long in them, fear of being denounced to the police effectually driving away all desire for a sluggish morning. By ten o'clock we were already downstairs, and making for the front door.

The hall porter called after us in a voice that seemed to us full of curiosity: "What I Going already ?"

"Yes, yes, we are in a hurry;" and without more ado we briskly left his company.

Condemned as we were to wait for evening before again venturing out into the country, we drifted aimlessly about the streets of Aix. But our stomachs clamored for a pittance somewhat more substantial than that with which we had so far gratified them. Since our last meal at Scharnhorst, that is to say, twice twenty-four hours, we had in all, and for all, eaten eight small tablets of chocolate-somewhat meagre fare. And now that the eighth and last tablet had disappeared we could discover no means of replenishing our larder. Un-provided with cards or food-tickets of any kind, to present ourselves anywhere either as a diner on the premises or a purchaser of comestibles would have been to denounce ourselves infallibly; if not for what we were, at least as persons whose irregular position recommended them highly to the curiosity of the police.

Good luck led us to a mechanical bar. There, at least, we thought, there could be no danger, the machine being endowed neither with eyes nor ears. We soon found out our mistake. If the machines were deaf and blind the same could not be said of the urchins detailed to watch over them. One of these, about twelve years old and as sharp as a razor, came and planted himself next to us, obviously all ears. I broke into a voluble flood of speech, and succeeded in allaying the suspicions of the young spy to such an extent that he at last left us, and went to carry on his small affairs elsewhere.

We at once prepared for a good feed, but disappointment awaited us. The only dish that was left was jellied mussels. We could do no other than resign ourselves to the inevitable. and it might be better than nothing. In return for forty pfennigs the distributor produced for our benefit seven mussels on a plate. Both of us returned twice to the charge. Then we departed, having failed to lose any great proportion of our hunger, but having gained an undeniable feeling of nausea.

In default of more solid nourishment we fell back on glasses of beer, absorbed at frequent intervals during our aimless wanderings. Unfortunately, it was Einheilsbier, which only had the vaguest of resemblances with the good, solid beer of peace-time.

One of these pauses we made at the Theatrellatz Tavern, where Munich Spartenbrau used to be served. Momentarily discouraged by our failure of the night before, we were afraid of having to spend an indefinite period between Aix-la-Chapelle and the spot we had marked out for crossing the frontier. It occurred to us that help from outside would be invaluable.

I had a good friend, almost a brother, on whose affection and intelligence I had always been able to count throughout the fifteen years of our acquaintance - Raoul Humbert. I knew him to be at Leysin (Switzerland) at the sanatorium " Les Fougres."

I wrote to him. I sent my letter in an envelope of the tavern, where he was to reply to me, using the name of Munder. Disguising my handwriting, I told him that with a fellow-machinist from the firm of Oerlikon, I was held up at Aix-la-Chapelle by an accident to my arm, sustained during a first and unsuccessful attempt to install the motor, that I hoped to have better luck with my second attempt, but that neverthe- less I should be glad of his helpful intervention in whatever form he could give it. The terms of my letter were of necessity ambiguous, but my friend Humbert would certainly decipher its meaning without difficulty. I may as well say now that the letter reached him-he has since shown it to me, with the tavern's stamp on it-but on that same day the newspapers announced that Garros and I had reached Holland in safety, and so he did nothing.

Towards evening we went into a sort of café. We were served with ersatz coffee, accompanied by a sort of tart, the crust of which was artificial-as indeed were the cream and the strawberries with which it was filled. Our stomachs did not receive it with any better grace than the morning's fourteen mussels.

Night came. Our previous failure would at least have served to teach us the lie of the land, so it was with greater confidence that we started off again towards the frontier. Alas ! we went farther astray than ever, only extricating ourselves with the greatest difficulty from the barbed wire and with only the satisfaction of not having attracted the attention of a patrol. Aix had the privilege of seeing our second return between three and four o'clock.

With no food save that which I have already described this new march of thirty kilometres left us thoroughly exhausted, and we began to fear that we would never succeed in getting out of the damned country. But we had to find a place to sleep in. I led Garros to an inn near the station, where I knocked while my companion waited at a distance. A sleepy woman opened to me. I said that I was called Schmidt, and asked her if a friend of mine, a commercial traveller, had had not inquired for me that night. She replied in the negative.

Then he hasn't yet arrived. He will very likely come by a later train, but he will certainly join me before long. In any case, I will take a room for myself and reserve another for him." My friend, strangely enough, arrived almost immediately. And now for a good sleep. We had earned it.

At midday Garros said: "Listen, old man. To-day is the end. Either we pass the frontier or we are done for. But it isn't after two days and three nights of almost total abstinence that we shall be in the best form for the last pull at the traces. At whatever risk we must have a good feed."

I agreed with him only too well. In order not to remain for ever at the inn we moved to another hotel in the same quarter. I booked two rooms for the sake of appearances. Then I called the restaurant attendant aside. " Look here," I said, "we have come a long way and are very hungry-only I warn you we have lost our food cards." He gave me to understand that, if I did not look too closely at the price, the matter might be arranged.

It was arranged. We were served with a dinner, washed down with wine, that would have been perfection save for a total lack of bread. It seemed that everywhere, even in this land of regulations, the severest of restrictive organisations could be circumvented. And that night again, beside the official menu endorsed by the police, we had an enormous steak with potatoes, an omelette and some jam. Nothing was lacking save the bread.

Well ballasted, thoroughly revived, we felt full of courage and spirits. Nevertheless, we redoubled our precautions. Once on our way, we took frequent hearings, in order to make no error in our itinerary, and at the slightest alarm we took refuge behind a bush or in a ditch.

At seven or eight kilometres from the frontier the immediate proximity of the principal guard-house was made clearly visible to us by its external illuminations-a huge electric light. In that vicinity the slightest imprudence would he the end of us. We advanced only on hands and knees, ears and eyes well opened. At last we came on a little stream that was noted on our map as marking the last line of sentries. But here we were condemned to a lengthy wait. We were in the first night of the first quarter of the moon, and it shed a considerable amount of light. Until it had set we could not walk, nor even crawl, in the open. We found that it took its time about it. Never had I realised how slowly the moon travels. We cursed it for its sloth. We even accused it of being an hour late according to the meteorological schedule announced for it in the Magdeburg Journal that we had consulted. How ever, neither the moon nor the newspaper was at fault; the error was due to an idiosyncrasy of Garro's watch.

At last the night was dark. We set off again, on all fours, until we came to a perfectly naked plain. Not a tree, not a house to be seen. No further doubt was possible-we were approaching the goal.

Nevertheless, we were worried by the fact that we could not find the landmark that had been indicated to us-a mountain peak that dominated the otherwise flat country. We could see no slightest trace of the smallest peak, yet we still felt that we were on the right track. This idea was confirmed by the sight, in the distance, of a brilliantly illuminated building, which we had been told to use as a lighthouse. But we had been told that it was the guard-house from which the frontier was watched, whereas in reality it was a coke factory situated in Holland itself. Yet, save for that error of identification, it was the same luminous landmark of which we had been told.

As for the famous mountain peak, which we saw later, it was no more than one of those huge slag-heaps that are so often found in industrial areas.

We advanced now flat on our stomachs, and crossed in that fashion a ploughed field which we saw to be traversed on our right by numerous footprints.

"That must be the route for the relief of the sentries," we said to ourselves. No matter-we must get on. Crawling thus we made barely five hundred metres an hour-and in what state of mind may be imagined-a curious mixture of terror and hope.

Now, twenty metres in front of us, there rose a little thorn hedge. In the breath of a whisper we said to each other that it must border the road along which, if our information was reliable, the sentries patrolled. At that moment we heard some one cough to our right. Garros seized my arm and pressed it, indicating that we must neither speak nor move.

Holding our breath, we did our best to disappear into the ground.

All at once the sentry who had coughed began to walk cowards us. Suddenly he stopped. We had the agonising sensation that he could see us perfectly well in the dark. But no, he went on, paused a few metres in front of us, and continued on his way to our left.

He came back, walked to the right, and halted.

Then we heard a voice, to which another replied. It was the conversation of people speaking face to face-nose to nose, judging by the tone of their voices.

Now, we knew that the sentries on that line were spaced at intervals of a hundred and fifty metres; so if one of them had moved to go and talk to his right-hand neighbour it was highly probable that he had thus opened in front of us a gap double the usual width. We must take advantage of it.

Crawling obliquely towards the left, we reached the thorn-hedge. Fortunately there were gaps in it, between the little trunks where they emerged from the soil. By groping, Garros found his and I mine. We slid through.

Beyond it the ground sloped slightly, and a metre and a half farther on a strand of barbed wire was stretched low across the grass.

The wire was arranged in such a manner as to trip up any body who passed, so that the noise made by his stumbling might warn the sentries. As we were craw in we felt the wire, and did not trip.

We found ourselves now in a little field, about a hundred metres wide. Still fiat on our stomachs we crossed it. A perfect hedge of barbed wire bounded it. It was the last obstacle. In one bound, taking no heed of torn skin or clothing or rifles or sentries, we leaped on to and over it, and in another we cleared a stream whose sinuous course marked the frontier. Then, with beating hearts, soaring spirits and smarting eyes, we literally fell into each other's arms.

We were in Holland! We were out of reach of the Germans.

Here end my souvenirs of captivity. It only remains to me to relate briefly the circumstances of our further travel.

From the point where we had crossed the last line of German barbed wire we took train for The Hague, where we reported ourselves to the French Ambassador. Garros never forgot, as I shall never forget, the charming manner in which General Boucabeille, the military attaché, the general's wife and the members of the French colony received us.

Then we took ship for England. The crossing was effected the usual manner, that is to say, under the protection of British destroyers. During the voyage if a mine or two were signalled no fuss was made - our ship and her escort knew well enough how to avoid them. I may note, too, that a German hydroplane attacked us, but its bombs made no victims in our flotilla: the inoffensive fish of the North Sea were the only sufferers.

At last we reached London, and from there we left for Boulogne and the front.

The nightmare was over. We were soldiers once more.

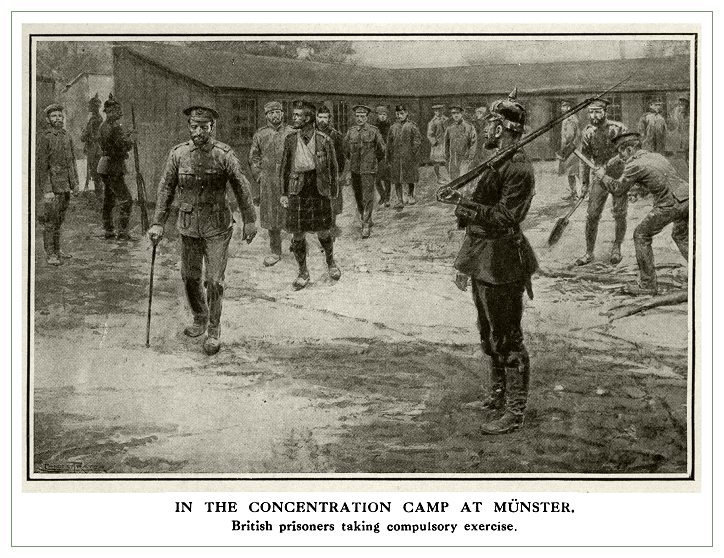

from 'The Times of the War' : a somewhat sinister looking illustration of prisoners taking exercise.

also from 'The Times History of the War' : Officers quarters at a prisoner of war camp.