- from

- 'the War of the Nations'

- a History of the Great European Conflict

- by Edgar Wallace

The Great Russian Retreat

- a coverpage from a British magazine - 'the Illustrated War News'

- texts from 'the War of the Nations' : see link for information on this magazine

- Russian Gains in the Carpathians — Severe Austrian Losses: 70,000 Prisoners —

- The "Battering-Ram Army" — The Russian Retreat — The Second Fall of Przemysl.

THE most dramatic events of the war have been the battles waged by our Russian ally. The Russians have had great successes, and they have experienced serious defeats.

The campaign in the east has been one of ever varying fortune, but of one thing there can be no doubt. The Russians have fought with a stubbornness and bravery unequaled in their whole history. Their lack of equipment, guns, and munitions has been a serious handicap to them in their war with an enemy who entered on the war fully prepared. Because of this lack of equipment the Russians were unable to place more than a limited number of troops in the firing line.

They have, of course, illimitable reserves in men to draw upon, but it became more and more evident as the campaign progressed that heavy guns and shells are the weapons which command success. Soldiers may be ever so brave, but no soldiers in the world can stand against such an enormous concentration of guns as was brought to bear on the troops of our Ally on the Dunajec. Some weeks after the fall of Przemysl on March 22, the Russian generals divined that a mighty blow. was coming, although they did not know where it would fall. As we shall see, it proved to be a sledge-hammer blow designed to drive the armies of our Ally from Galicia, and to deprive them of the fruits of their brilliant winter campaign in the Carpathians, throwing them back in effect to their situation in the early autumn.

I shall resume the story where I left off in a previous chapter. Przemysl had been wrested from the enemy, and it seemed that the Russians were free to press on to the plains of Hungary.

From the last days of March and throughout April the Russians were gradually creeping down the southern slopes of the Carpathians. Amidst the great fir forests the bivouac fires lit the dark nights ; their advanced posts held the ruined villages that lay in the hollows and folds of the southern spurs.

Winter was passing, the snow line was creeping upward and the gulleys and channels which scar the slopes of the hills were roaring torrents of opalescent water. Every roadway was a streaming rivulet, the cozy trenches which had been cut on the side of the hill were so many brooks, and there was in the air that genial warmth of spring which spurs the sap of the barren forests and speckles the dark firs with vivid points of green. Spring was here, and well might the Russian rejoice. His hold upon the passes seemed assured, his sinuous line was creeping across the crests toward Uszok, and his guns were already hammering at the outlying trenches which protected the Austrian flank. Day and night, with a ferocity beyond description, the battle raged on that perimeter which protected the last and the most important of Austria's communications through the Carpathians.

Below, hidden in the spring mists and beyond the gently rolling hills to the southward, lay the rich Hungarian plains, tilled and furrowed and sown.

Spring would bring green shoots over vast acreages, late summer would see enormous yellow harvests awaiting the reaper's hand. Upon the gathering of this harvest much — not everything — depended. The Central Empires needed every bushel of corn that could be poured into the national granaries, for the strangle-hold of the British Navy was upon the sea, and the Germanic ships lay rusting their hulls in twenty harbours. The attacking Russian had an eye to this harvest, and the men of the Russian armies, who knew all that a good harvest signified, saw their immediate objective, and knew how much depended on their being able to sweep forward in the summer and destroy the new supply before it was gathered.

If the Russian knew, the Austrian knew still better, because upon him would fall the weight of failure, upon his populations the pinch of shortage. Attack after attack had been delivered on the Russian front to force the Russian back to a "safety line." .Then Przemysl had fallen, and, greatly reinforced, the Russian renewed his attack, extending the ground he held and consolidating the position he had already gained. It seemed at this point in the progress of the campaign that the Russian position was well-nigh invincible. He had cleared the whole of Galicia, from Lemberg to the line of Dunajec. Przemysl had fallen into his hands, Lemberg itself had developed into a Russian city, and the Carpathians had, in part, been spanned, and in other parts were threatened.

At this time the Commander-in-Chief of the Russian armies was entitled to be optimistic in his survey of the situation, and in a despatch he authorised on April 18 he was full of confidence. After the fall of Przemysl, he pointed out that in the principal chain of the Carpathians, the Russian forces held only the region of Dukia Pass. All the other passes — Lupkow and further east — were in the hands of the enemy.

"In view of this situation, our armies were assigned the further task of developing, before the season of bad roads due to melting snows began, our positions in the Carpathians which dominated the outlets into the Hungarian plain. About the period indicated, great Austrian forces, which had been concentrated for the purpose of relieving Przemysl, were in position between the Lupkow and Uszok passes.

"It was for this sector that our grand attack was planned. Our troops had to carry out a frontal attack under very difficult conditions of terrain. To facilitate their attack, therefore, an auxiliary attack was decided upon on a front in the direction of Bartfeld as far as the Lupkow. This secondary attack was completely developed.

"On the 23rd and 28th of March our troops had already begun their principal attack in the direction of Baligrod, enveloping the enemy positions from the west of the Lupkow Pass and on the east near the source of the San.

"The enemy opposed the most desperate resistance to the offensive of our troops. They had brought up every available man on the front from the direction of Bartfeld as far as the Uszok Pass, including even German troops and numerous cavalry-men fighting on foot. His effectives on this front exceeded 300 battalions. Moreover, our troops had to overcome great natural difficulties at every step.

"Nevertheless, from April 5 — that is, eighteen days after the beginning of our offensive — the valour of our troops enabled us to accomplish the task that had been set, and we captured the principal chain of the Carpathians on the front Reghetoff-Volosate, no versts (about 70 miles) long. The fighting latterly was in the nature of actions in detail with the object of consolidating the successes we had won.'

"To sum up. On the whole Carpathian front, Severe Austrian Losses: between March 19 and April 12 the enemy left in our hands in prisoners only at least 70,000 men, including about 300 officers. Further, we captured more than 30 guns and 200 machine guns.

"On April 16 the actions in the Carpathians were concentrated in the direction of Rostoki. The , enemy, notwithstanding the , enormous losses he had suffered, delivered, in the course of that day, no fewer than sixteen attacks in great strength. These attacks, all of which were absolutely barren of result, were made against the heights which we had occupied farther to the east of Telepovce."

I have already pointed out in this publication that the attack upon the Carpathians and the forcing of the passes were more or less accidental to the Russian plan of campaign.

He had no reason for moving on a front which compressed and restricted his advance and must necessarily cramp . him' when he came to deploy his armies on the southern slopes. His way into Hungary led, naturally, past Cracow, through the broad Moravian Gap, near where Napoleon had fought Austerlitz, and such a progress enjoyed the inestimable advantage of threatening on the one hand the plains of Hungary, and on the other the rich district and province of Silesia. But such an advance was denied by the existence of Cracow, the fortress town which stood in the same relationship to the Moravian Gap that Przemysl bore to Uszok, and also by a rapid concentration of enemy forces on the Silesian frontier whenever there appeared the slightest likelihood of an advance developing in that direction.

For Silesia was the vital point in the German defence. A region filled with vast industrial works," with coal mines, factories, and all the machinery of industrial creation, it was one of the richest, and certainly one of the most prosperous, provinces of Germany. As East Prussia was the pleasaunce of Junkerdom, containing, as it did, his fine chateaux and hunting boxes, so was Silesia the region from which he largely derived his income. The wealth of the Junker depended mainly upon the return he received from his investments in industrial Silesia. Since the Russian was denied the easy advance, he had perforce to accept the other alternative and push his way through the forbidding-passes of the Carpathians, and even here he was not a free agent, for the occupation of the Carpathian crests came as a consequence to the failure of the Austrian to relieve Przemysl.

So we had this position ; the Russian had pressed down through the Dukia, the Lupkow, and a few small passes, until he threatened Bartfeld on the west, and the southern approach to Uszok on the east. His line crossed the crests of the mountain westward, of Uszok, curved up to Stryj, and was continued more or less irregularly to the line of the Dniester, whither, after their defeat on the Bukovina, the Russian troops had withdrawn.

The Russian had done surprisingly well, surprising, because apparently, for all his shortage of ammunition, due largely to the fact that Archangel was icebound, and that we had failed to force the passage of the Dardanelles, he was seemingly keeping pace with his well-organised and highly industrialised neighbour.

The grip of winter had hermetically sealed the Russian coastline. There only remained one track of rail, running four or five thousand miles, from Moscow across the Siberian Plains to Vladivostok and Port Arthur, upon which he could depend for the trickling stream of munitions, which his erstwhile enemy and now his Ally, Japan, could feed to him. Russia was not a highly industrialised country, and though her people worked with a singleness of purpose beyond all praise, it was obviously impossible that the Russian should supply his own deficiencies. ,

Therefore it was, as I say, all the more remarkable that Russia should be able to give shot for shot throughout the winter and the early spring. Our satisfaction at this state of affairs was not well founded. Throughout the winter there had been going on a mighty accumulation of shells and material behind the German front at Cracow. German and Austrian factories had been working ceaselessly, turning out the steel cases for shells by the million, and dispatching them to the arsenals of Germany and Austria, where they were filled with high explosives.

It is impossible not to admire the German effort, which represented war organisation at its very best. Man, woman, and boy went about their silent work, creating, packing, and dispatching those wonderful reserves of ammunition which were to blow a way from the Dunajec to the San. The Russian position on the Dunajec ran practically at right angles from the western end of the Carpathians to the Vistula. It was the left side of a box, the bottom of which was represented by the Carpathian crest' which enclosed Galicia, and allowed of the free movement of Russian armies to and from the Carpathian passes. Apparently one Russian army defended this important line, and that one army had withstood all attempts to pierce or to crush the defence it offered. Splendidly entrenched, covered by rivers, and occupying lines of small hills, it was supported by innumerable redoubts, field fortifications, and, in places, by quadruple stretches of barbed wire entanglements.

"It was much stronger than the German defences on the western side, and we knew that nothing short of the arrival of absolutely overwhelming forces would have any effect," wrote a Russian officer. But, unfortunately, those overwhelming forces were creeping up. General Dankyi, commander of the Austrian Army which straddled the Nida, moved tentatively forward, and created, by a series of strong assaults, the impression that an attack was developing at this point.

Simultaneously a new German army moved up south of Cracow, and began to move along the line of the embankments of the main railway, which in time of peace runs with little interruption from Lemberg to Cracow. I have called this a German army because it was under the command of the German general, Mackensen. It consisted of five strong German corps and the five best Austrian corps, and it was supported by the most tremendous quantity of artillery which has ever accompanied any army in the field. On its right was a further army of five Austrian corps, and the forward movement was supported by an attack of yet another five corps along the slope of the Carpathians towards the Dukia Pass.

The central army under Mackensen has been described as the " battering-ram army." There never was a better description. Put at a narrow-front, it was intended to break the Russian line at a vital point and at whatever sacrifice of men, and this purpose it accomplished remarkably well.

The main attack opened on Thursday, the 20th April.

Mackensen had taken from the West and from the East Prussian front the very best of his corps, and these had been replaced by new troops, whose arrival in the West had been announced by the attack upon the Canadians' line, in which poisonous gases had been employed, and by the beginning of the second battle of Ypres. This is a point which should be remembered; the attack upon Hill 60, which has already been described, was due primarily to -the knowledge which Field-Marshal Sir John French had that these exchanges were being made, and the big movement towards Russia was in course of progress at or about that date. It was earlier than was expected. I think I am right in stating that the German advance in Russia was first planned for the first week of June, or at earliest in the last week of May.

The reason for the change of plan is apparent. It was not wholly to save the harvest in Hungary, which would not be threatened until then ; it was not even to take advantage of Russia's known shortage of ammunition : it was, in fact, to scare Italy, at that period debating the question of war, that the movement was accelerated.

I make this digression because it will be necessary later to refer to these incidents when considering the events which led up to Italian intervention, and which marked the progress of her negotiations.

On the 29th and 30th, therefore, the battering-ram moved, and its objective was the juncture of the Rivers Dunajec and Biela. Here stands, or stood, the important town of Tarnow, which was situated on the western slopes of a mountainous group, holding, amongst other important places, Sanok and Jaslow, which is to the north-west of the Dukia, just as Sanok is to the north-west of the Lupkow.

The assault was heralded by the most terrific artillery fire that had ever been directed against entrenched soldiery. Guns of every calibre were trained upon trench upon trench of earthwork, extraordinary quantities of high explosive shells and a veritable rain of shrapnel were poured upon the devoted defender.

"The noise was something infernal," wrote one who was present and, mercifully for him, lived to tell the story. " It was as though one stood in an enclosed railway station and a hundred trains were rushing through at full speed, each engine emitting the most ear-piercing shriek, and this din was continuous for three or four hours. Add to it, if your imagination is equal to the task, the thunderous crash of continuously exploding shells. Communication was impossible. You had to raise your voice to a shout to let the next man know what you were speaking about, and when it is remembered that ninety-nine out of every hundred men were stupefied, so as to be almost insensible and unconscious of aught save this shrieking inferno, you may realise the almost impossibility of controlling your men."

The Russian soldier knew one thing, and needed no instruction at all upon that point. He was to hold on to the very last man, and he was to die at his post if need be.

Every man of that gallant seventy thousand — and there were no more — who held the screen line, knew that upon his tenacity depended the safety of the armies operating on the southern slopes of the Carpathians.

Let this screen be broken ; let it be so hammered back that its left uncovered the Dukia, and the Russian army struggling through that .pass must be annihilated or surrender. Outnumbered in some places by ten to one, with their trenches blown in, burying hundreds of men alive, with the superiority of the enemy artillery smashing their guns as though they had been of wood, and with the almost impenetrable mass of German and Austrian infantry advancing to complete the work of the guns, the case of the defender was indeed a terrible one. Yet, such was the courage of the men and their initiative, that even as the German guns ceased and the great horde of riflemen came sweeping across the conquered ground, the ragged line of Russian infantry reformed again and again, and advanced with the bayonet to challenge their overmastering enemy. -,

Again and again, in a score of minor combats, waged with a ferocious intensity which defies description, the Russian infantry thrust back their pursuers, re-established themselves in yet new lines of trenches, only to be again driven out by the fire hail of the German gunners.

In the meantime, the Russian armies to the south of the Carpathians were being hard-pressed by an enemy which had suddenly increased in size, and was almost as prodigal in its use of ammunition as was the "battering-ram army."

The growing intensity of the fire, coupled with the information he was receiving through the pass, disclosed to the commander of the 3rd Russian corps the seriousness of his own position. Further eastward the Russians were already retiring through the Lupkow, and now with the pressure on his front growing in strength every hour, the General began a retirement which was in every way admirable and must pass down to military history as a classic example of a retreat under extraordinarily adverse conditions.

Harassed on his flank by strong Austrian detachments, which had driven in the outliers and were commanding his line of retreat; with an advance guard action to the north, and a rearguard action to the south, simultaneously directed, the Russian army moved swiftly in an endeavour to reach the northern end of the passes before the battering-ram had driven the screen so far back that it was a screen no longer. Not a portion of that retreating force but was swept by shrapnel and sprayed by machine gun fire from the woods and heights which held the now eager enemy, yet with a steadfastness and a stolidity beyond human praise, in the face of this attack, the 3rd Russian corps "waded through blood to safety."

Men fell in droves ; general officers and their staffs came under the same hail; the General himself was wounded, but, battered and bruised, he brought his torn remnants of an army to reinforce the retiring screen, and to face about to hold up the Austrian forces which were now moving through the passes. All day long the fight went on, and night brought no rest to the weary soldiers.

Star shells and flares made the scene as light as day, blazing pine forest and burning farm were so many beacons to mark the progress of the victorious army.

Behind the Russian line, on a score of deep rutted roads the steaming gun teams were hauling back to safety the Russian artillery pieces pitifully under-munitioned, and on the main road itself the sight presented, in the light of the calcium flares, was a remarkable one.

The broad road had been left open for the quick moving light artillery, and up and down the space left the swift motor cyclist couriers were passing between the desperately battling front and the General Staff headquarters, which had been established, sometimes at the little farmhouse, sometimes grouped about a dozen motor cars at the side of the road, and, more often than not, were represented by a knot of great-coated figures standing in the pitiless rain.

The mighty phalanx of German and Austrian infantry pushed slowly and doggedly forward, for all the world like a monstrous column of ants that swamped out impeding fires by sheer weight. The very industry of the defending screen against "the" ram ".calls for recognition. You may picture the rough engineer carts lumbering from base to front, laden with gigantic reels of barbed wire to be hastily threaded from tree to tree ; you may. picture the toiling engineers felling plantations, digging frantically in the road which seemed to be abandoned, and packing with feverish hands the deadly constituents of mine and pitfall; and all the time, behind the breastworks they had made, and knee deep in the watery ditches they had dug, the indomitable, grey-coated infantry of Russia shooting steadily and surely at the irresistible enemy .on their front.

At first the task of the German had seemed an easy one. Though it was only with difficulty that he had dislodged his enemy, yet once dislodged and the line pierced, it seemed that nothing could save from annihilation the armies on his front.

The resistance he met afterwards was not only astonishing, it was maddening. Those who had planned and schemed for the overthrow of their enemy, who had spent the whole winter devising means and anticipating difficulties, were now confronted by elements which had not been foreseen. They had depended upon striking an initial and so demoralising a blow as to render the future of that campaign beyond any question. The blow had been struck, all had happened as they had planned — with one exception, no account had been taken of the natural tenacity and the dogged fearlessness of the Russian legions. Before this impending tragedy all the best qualities of the Russian peasant came to the surface. With a heroism that was almost divine he faced the peril; standing to his death, in that urgent moment of his country's crisis he gave the best that was in him.

The line was bending back slowly to the north where the Russian, strengthened by the fact that the Vistula offered him immunity from flank attack on his right, was contesting every inch of ground, more rapidly on the left where the fraying columns brushed the northern slopes of the Carpathians, uncovering the passes and collecting at their dishevelled ends the stragglers who were still pouring through the Carpathian gorges from the Hungarian battlefield.

River by river they held, but now the enemy's strength was increasing as his southern armies came into action, and the retreat took a new direction. From due east it moved north-east, falling back on the line of the San and the great fortress town of Galicia.

So far the enemy was directing the line of retreat, at so far the initiative lay with the "battering- ram," which still kept to its railway, and still moved forwards slowly to its appointed destination.

That destination was Przemysl, and more particularly the forts of the San to the west and north of that town. Again the tide of war was to sweep the storm city of Galicia.

In a figurative sense Przemysl was a sorely battered city, though in truth no shell had troubled the civilian serenity of the town. One siege she had withheld ; to one investment she had fallen her official language had undergone some change incidental to Russian occupation, and now at a moment when it seemed that her fate was sealed, and Edict of Vienna must be replaced by Ukase from Petrograd, there came the challenging armies of the Kaiser, and the heavy boom of artillery filled night and day with trembling sound.

You must understand something of the topography of this great fortress to appreciate to its full the German plan. The city is cut in two, a smaller part to the north, and the larger part. to the south and south-east by the San, which winds convulsively through the region and affords some little protection to the defenders of the town. Out of Przemysl, on the north bank of the San, runs the main railway to Grondow, and almost parallel, and running very nearly due north, runs a main road which skirts two fairly high hills in the neighbourhood of Zurawica and passes through Malkowice. Almost due east from the .city is the main line to Lemberg, and this, it may be pointed out, is the only railway line which the reader has any need to remember. I

Along this line the Russian Army was provisioned and reinforced; along this line must come any danger which threatened the German hosts. The main road to Lemberg runs parallel with the rail, crossing it at a point due north of Pleszowice. The vital points in the defence of Przemysl were obviously those points to which the enemy could nearest approach, the railway line.

He had partially encircled the town to the north and to the south, he had driven his infantry forward to the very wires of the Russian defences ;he had at one moment broken the Russian line and put his foot in the defences of Hassakow, which is to the south-east of Przemysl; he had succeeded in carrying three or four forts to the north of Przemysl, only to be' driven out again but gradually, and it seemed inevitably, he was tightening the circle about beleaguered Przemysl.

The fights on the earlier days of the stupendous move were as nothing compared with the fury of the combat which waged threatened points. The trenches at Hassakow ran with blood, men died not by the hundred or by the thousand, but by the tens of thousands, and the opposing lines were locked so closely in that life or death struggle, that a hundred yards' gain one side or the other involved sacrifice of life more serious and on a larger scale than that entailed by any battle of similar dimensions and on as short a front.

The organisation at short notice of food and munition supplies to the rear of the new line was one of the great commissariat accomplishments of the war. Undoubtedly, over so vast a front the Russian experienced very grave losses both in men and material, but no loss which was felt in the retreat was of a character seriously to jeopardise his safety.

In the acute triangle at the apex of which lay Przemysl, he had gathered his reserves of men and supplies, and after the first shot had been withstood and he found, probably to his own surprise, that his outer defences were intact, he settled down to the serious business of holding fast to a position which he had gained at such a cost.

And here began one of the most extraordinary pieces of reorganisation which has ever been witnessed in the progress of the campaign. In his retirement the Russian had lost heavily, as was only inevitable. He had lost stores and the wherewithal to carry those stores; he had lost guns, munitions, large quantities of horses, and to a very great extent the machinery for distribution had snapped. He had to provision immediately a very hungry army, to feed famished men and starved batteries.

Ammunition had been used frugally but effectively, some batteries had only ten rounds of high explosives per day, some guns shot less than 50 rounds in each battle. The Russian had not the accumulation of stores that was necessary if he were to fire shot for shot. Trains were coming at full speed from Archangel and from the great arsenals in Russia, with the ammunition he desired, but the stream of material was a trickling one, and not yet near to his requirements. It had been due to the overwhelming quantity of ammunition used that the German had battered his way forward.

The enemy was prodigal of ammunition to achieve his purpose of driving the Russians to Przemysl and Lemberg, and what the Russian forces had to face may be easily gathered from an official note from Petrograd, transmitted through Reuter.

"On one short section the enemy, during a lull in the fighting, cannonaded our two army corps with about 1,500 guns, a great part of which were heavy pieces of medium calibre and 42- centimetre howitzers.

"When the action of the artillery was particularly violent prior to an assault the enemy discharged about 700,000 projectiles in four hours, in other words, a quantity of munitions the transport of which would require over a thousand wagons.

"This quantity of projectiles is double what is necessary for a six months' siege of a great and well-provisioned fortress.

"Another 700,000 projectiles had been intended for the development of the offensive, but the enemy were apparently largely exhausted by May 10, when the first slackening in the onslaught of General Mackensen became apparent.

"Generally speaking the enemy uses in an attack on our positions ten projectiles of medium calibre, weighing over 800 Ib., against each of our riflemen holding a space of about a yard on the front of our trenches.

"During the advance of General Mackensen from Gorlitze by Jaroslav to Naklo (north-east of Przemysl) an officer holding a responsible position received within a very short space of time about 10,000 bombs on his front. In presence of such a violence of fire, without speaking of serious losses, all within the sphere of its action become more or less bruised or stupefied.

"It is evident, however, that even the very numerous factories which manufacture projectiles cannot long supply heavy ammunition which is expended at the rate of 200,000 an hour. It appears, in fact, that the Germans have exhausted the supplies of Cracow and several other of their fortresses, and that their infantry, spoilt by the support of their artillery, and accustomed exclusively to attack an enemy stupefied or poisoned, will very shortly have to fight under very different and more difficult conditions."

To bombardments of this violence the Russians could make no effective reply, and when he reached Przemysl, he had to squander his reserves and trust to the supply trains bringing him further assistance. He must create new supply stores and organise the distribution of food and water; he must bring down that narrow line of road men by the hundreds of thousands, fill the gaps which had been made in the retreat, and that the commissariat succeeded as they undoubtedly did succeed was as creditable to the Russian army as any victory it secured in the field.

The "battering-ram" crossed the San and moved along the River Lubczowka, first carrying the sometime fortress town of Jarizlow. Further than this it might not go. The yielding line became as a line of steel. Russian reserves came to the front, new and heavy concentrations of artillery were brought against this shoulder to shoulder mass, shrapnel burst over the crowded ranks, sweeping to destruction thousands of men who were far from the actual fighting front. There was no wavering, only an internal crumbling and shrinking to the centre.

Again and again Mackensen put his best troops at the Russian defence, and again and again, decimated by shell of machine gun fire the phalanx jarred itself to a standstill. The attack which was delivered by the Austrian to the south of Przemysl fared no better.

It carried in the course of a bloody fight the triple trench line which the Russian held, and poured up the glacis of the advanced works which our Ally occupied, only to be driven, first across the little river which protected Hassakow on one side, and then through the smoking streets of what had once been a little village, before the red bayonets of Russian infantry.

For eighteen days the fight raged furiously, Lupkow in the east was carried by the Germans, and a tremendous assault was delivered upon the Russian position along the banks of the River Stryj. Stryj lies further eastward, and the Stryj-Dolona line represented to all intents and purposes the extreme right of the Austro-German advance.

General Lingsengen, who commanded five Austrian corps, attacked here on a narrow front, pierced the Russian line, and for a moment the- position was critical; then the defenders closed, leaving in their rear some twenty thousand men who were annihilated.

The pressure which the enemy was exercising upon Przemysl was one against which the Russian could not possibly withstand. Przemysl had been created by the Austrians to guard the Uszok Pass from attacks delivered from the north. Its position as a defence against an army moving from the south and from the west was a perilous one.

Moreover, it had ceased to be a fortress in the strictest sense when the Russian had taken the town, for the enemy had destroyed most of his guns, and at any rate certainly destroyed a vast amount of ammunitions. It was impossible in the space of time which the Russian had to create munitions of the calibre and of the character necessary to feed his guns adequately, so that the Przemysl defences were largely certain locations in which guns had been placed, and which enabled their new tenants to secure advantage of cover and of view. Partially successful attacks delivered to Hassakow and to the north threatened to isolate the Russian garrison, and in the last days of May the Russian Commander-in-Chief began a well-planned and smoothly executed evacuation of the defence lines.

On June 1 this had been completed, and when in the early morning the German batteries opened a terrific fire upon the defences, that fire was not .answered, for the fortifications were deserted, and the Russian General, on his new and shorter line to the east of the city, offered a stronger front than ever to the enemy. As a result of this withdrawal the Grand Duke Nicholas had shortened his line by twenty-two miles and enormously increased his power of defence, had added also prestige to the Russian Army, for he had shown that he was not prepared to sacrifice military advantage from any consideration of sentiment. It was computed that by his retirement he not only saved divisions from capture, but he thickened his line to this extent.

The task of the Russian General in carrying out this retirement was one of enormous difficulty. It must be remembered that all the time the German was endeavouring to break through the line not only at Hassakow, but further to the eastward at Stryj, so that not only Przemysl but Lemberg was threatened. At the same time it was harassed from the north and north-west, and even at the point of the wedge about the Galician town numerous attacks were kept up day and night.

Every man who could be spared to hold the threatened points was put into the firing line, whilst in Przemysl itself a small army was engaged in removing accumulations of stores, Austrian weapons which had been taken from the enemy, material of all kinds, and the regimental and divisional archives from the places which had been taken over by the Russian authorities on their arrival in the town.

It was significant that the Russian destroyed and attempted to destroy no public building or any bridge in the town itself. It was even more significant that when the attacking lines -closed in on the town, and for the first time in the history of the war shells began to reach the suburbs, the Russian retirement was accelerated. Our Ally did not doubt that he was to return, and he wanted to return to a town which would eventually be a part 'of the Russian Empire, and find that town intact.

Day and night the broad streets of Przemysl rumbled to the ceaseless lines of army wagons moving westward. The Russian even took with him the cumbersome pieces of heavy artillery which he had removed from the Austrian fort. More than this, the deliberate character of the evacuation is evidenced in the fact that he removed the thousands, some say tens of thousands, of wounded who were in the hospitals of Przemysl.

“When -all was ready, the word went round, from front to front, from trench-line to trench-line. Somewhere to the east of Przemysl Russian engineers had thrown up huge earthworks, had built new and strong trench-lines, had created gun emplacements, cunningly concealed from view, and had provided a large number of Maxim batteries in the more advanced lines, to cover the retiring infantry.

In the middle of the night, as though they were at manoeuvres, and each following an appointed road which had been laid down by the General Staff, the great columns of Russian infantry moved back to take up their new lines. Overhead shrapnel and star shell illuminated the night, and in the thunder of their guns the German failed to detect the absence of any answering roar. At 3.30 .in the morning, just as dawn was breaking, the German infantry rushed forward in a succession of lines and charged the first of the Russian trenches. They found dummy guns, but no men. The road to Przemysl was open, and at 6 o'clock in the morning the first of the Bavarian corps swung into the central square, and were greeted, as the German Press tells us, "with acclamations" by the inhabitants of Przemysl.

It was a barren victory, and of booty there was practically none. "The booty," says a German communiqué, "cannot be estimated," and for a very excellent reason. And so Przemysl, that greatly tried town, came again into Austrian .occupation. Again were the great cafes crowded with Austrian officers, and save for a notice board or two in Russian, and occasionally a proclamation pasted upon the blank walls in the same language, and the graves of Russian soldiers in the big cemetery outside the town, there was no sign that it had ever changed hands.

The re-occupation of this "fortress" was no occasion for joy on the part of the inhabitants. The return of the German was the informer's opportunity. There were people to be denounced, people who had shown too great a friendliness to the Russian officers; supposed spies to be hunted out and shot. All the minor atrocities which accompany an Austrian occupation were witnessed.

- pages from 'the War of the Nations' with scenes from Galicia in 1915

- The Loss of Lemberg

- by Edgar Wallace

- The Great Russian Retreat 2

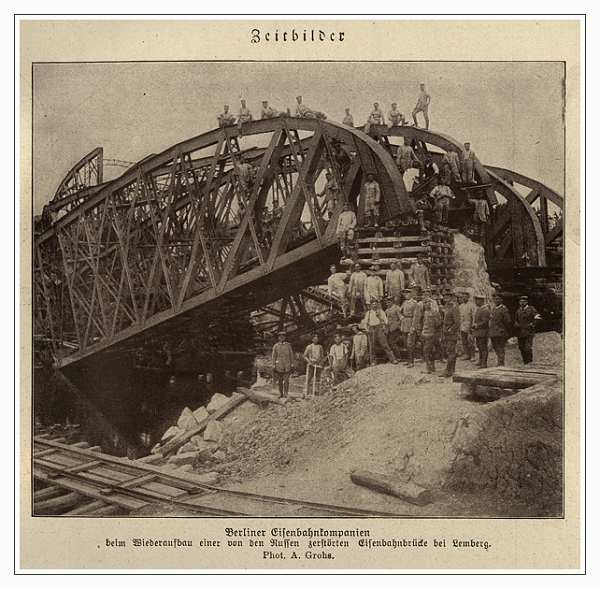

- a bridge near Lemberg blown by the Russians

- from a German magazine : 'Zeitbilder'

Orderly Evacuation of Przemysl — Russia's Great Commanders

WE left the Russian armies at the moment when they had concluded their evacuation of Przemysl and had fallen back upon prepared lines to the East of that fortress.

A fortress it was in name only. Its emplacements were chaos, innocent of armament, its munitions-stores were empty and wrecked with dynamite, its bridges were destroyed, its railway lines torn up and the very embankments shattered. Yet the Russians did not touch one public building or display their chagrin by the firing of a single house. They had come to Przemysl and brought order and authority with them. They left Przemysl with no other memory than the justice of Russian administration and kindliness and sympathy of the Russian officials.

All night long, while to the west of the fortress the great guns were crashing incessantly, Przemysl had been the scene of orderly activity. Regiment after regiment, battle worn and weather stained, came swinging through the main street singing as they went. In the morning the enemy entered Przemysl, finding a few wounded prisoners and nothing else. The Germans might have stopped here, but they were committed to two things, the first of which was "'the destruction of the enemy on ,their front, the division and annihilation of the Russian Armies which were opposed to them.

The Orderly Evacuation of Przemysl second was consequent upon the first, namely the freeing of Galicia from the invader's presence, General Mackensen had to halt and rest his battering- ram army, his ten corps sadly bruised and attenuated by the stress of constant attack, and support them by large reinforcements; his master of ordnance had to wait for further mammoth supplies of shells.

They were quickly forthcoming, for the railway to Przemysl had been built as fast as the army progressed, some six miles a day, and long trains laden from end to end with shells of every calibre moved day and night toward the army base. From now Mackensen's plan was largely influenced by the enormous losses he had sustained in the course of the fighting. He had hoped to achieve so crushing a victory by the time the army reached Przemysl as would allow an increase of mobility on the part of his forces. So long as he had the intact Russian army on his front, it was necessary that he should keep to the rail, and should support his attacks by the employment of that heavy artillery which had been mainly responsible for pushing the Russian to the east.

With the separation of the Russian Armies he could afford to tackle the task of destroying the disintegrated elements without the aid of his heavy artillery, but so long as the front was unbroken he was pinned to slow progress along the railway toward Lemberg. The Russians had succeeded in throwing lack the' enemy forces to the north of Jaroslav, recognising that Mackensen's advance must come from that direction, and desirous of obtaining not only manoeuvring room but time for the withdrawal of stores.

A heavy Russian attack was delivered at the German position at Sieniawa. The enemy was thrown lack eight miles, allowing the main body of the Russian Army to cross the river in the rear, leaving to a few weak forces the task of holding up the enemy when his inevitable counter-attack was delivered.

The Grand Duke Nicholas had only one desire, and that desire was to effect his retirement without endangering his units. The retreat of the Russians, harassed by the huge Austro-German Armies pressing on their heels, will live as a great achievement.

The Grand Duke had to lose men, and, indeed, he lost very heavily, but it was vital to the Russian plan that he should fight without losing whole corps such as he lost in the retirement to Narew, without seeing his army pierced and its components separated, as they were after that battle. If Przemysl could not be held, no less could Lemberg. The town was not fortified, and the only position which offered a chance of an effective resistance was the position of the Grodek Lakes, the chain of swamp and water and minor heights to the westward of the Galician capital. Here the Russian was at a considerable disadvantage. The Grodek line had been organised for defence by the Austrian at a previous date, but organised to throw back an attack from the east.

The Grand Duke had to hold Grodek against an enemy who was coming from the west, and this he succeeded in doing for two days, and might have continued doing so but for the fact that far away to the north General Mackensen, moving up to the retiring Russian Army, hammered his way into Rawa Ruska and threatened the envelopment of Lemberg from the north. The German left was now pressing forward and adding to the Russian burden. All the German cavalry that could be spared was massed at this point with an object which may be described at a later period.

The loss of Rawa Ruska determined the Grand Duke to surrender Lemberg. He was fighting for time, fighting too for the integrity of his armies, and fighting under a disadvantage which did not earn the notice it deserved, for he was without the invaluable assistance and leadership of Russia's greatest general. General Russki. Russki had retired on the ground of ill-health, after the retreat to Eastern Prussia. He was the great inspiration and genius of the Russian soldiery. They gave to him the worship which is accorded to very few men; in him they had supreme and absolute confidence ; and the appearance of Russia's Great Commanders Russki and his orange tyred motor car on a battle-field had the moral effect of the arrival of a division of reinforcements.

In general, the leadership of the Russian Army, and particularly that of General Ivanoff, was beyond praise. Ivanoff's third corps did wonders, yet in spite of this, the absence of Russia's fighting general from the field must have contributed largely to the German success.

All along the lines the battle was raging with fierce intensity when the evacuation of Lemberg began. It was a repetition of Przemysl. There was the same order, the same system, the same unswerving discipline, and the Russians were out of Lemberg, lock, stock and barrel, hours, before the advance guards of the Austrian Army began to feel a cautious way through the suburbs of the city. If they were fighting for time in the north, the Russian armies on the Dneister were fighting for space. Lemberg's fall made a retirement of the Russians from the Dneister inevitable. At this point the enemy was wholly composed of Austrian units, and in no battle had the Austrian proved a match for the armies of his great neighbour.

The battle ground extended for forty miles on the southern banks of the Dneister, but it was in the region of Novilov, with its heights and its picturesque villages nestling the hills that the great battle was fought out against Linsingen's army: Too precipitate a retirement in that region might have meant the envelopment of Lemberg from the south, might, indeed, have brought disaster to the retiring Russian army. The Russian general needed breadth of front so that his retirement could be carried out in an orderly and an unhampered manner.

At one point of his line, the enemy was pressing far too closely, and had succeeded in crossing the Dneister, pushing a wedge into the Russian line. The situation was serious, how serious was not realised by the people of Britain, who were watching the greater struggle, as it seemed, outside Grodek.

The Austrians had thrown their bridges across the Dneister and were rapidly concentrating troops upon the northern bank.

They had brought up to the heights commanding the river all their available artillery, and gradually the Russian line was sagging. There was only one thing to be done, and the Russian general took that course. Without any warning, he brought up all his reserves, hurled them at the attacker, and drove him back to the bank and to the hills. He crossed the Dneister by the enemy's pontoon bridges, and pushing at the enemy's right, carried not only the fortified villages which the enemy had organised, but took the hill behind. In some places the issue was for long in doubt. First one and then the other side seized upon some vantage place.

From behind the walls of ruined farms and the shelter of hastily constructed barricades across village roads, the enemy resisted desperately. First one and then another position fell into Russian hands, the full strength of the' army was being hurled day and night at the Austrians, and presently the weight told and the Austrian army fell back on its reserves. In these desperate battles along the Dneister, and especially in the endeavour to seize the position of Novilov where the railway crosses the river, the enemy lost 160,000 men, killed, wounded and prisoners.

Once he had his enemy demoralised the Russian general did not wait. His task was not to pursue foolishly, but to retire so that his line would conform with the line which was being taken up to the East of Lemberg. Instantly his army was set in motion, the river was again crossed, and leaving a few regiments behind to hamper the crossing, the General moved his main army back upon shorter lines, and this manoeuvre he carried out with such success that the enemy were unable to recover in time to occasion him any serious loss.

To the north of Lemberg the retirement was. being carried out with the same systematic thoroughness. Attack and counter-attack marked the steady retreat. All the time, the armies were fighting for clear ground. The Grand Duke's object was to fall back in some cases on the eastern bank of the Vistula, and to straighten out his line so that it ran from before Warsaw to before Kholm. And here, at the end of June, we must leave the Russians for a time. No praise can be too high for the unshakeable resolution with which the Russians were conducting their vast conflicts. There was no cause to search for the reason of the Russian retreat, a retreat which had obliged the Grand Duke to give up the whole of Galicia which had been conquered in the previous Autumn.

The retreat began in April, when on the Dunajec the Austro-German armies attacked in overwhelming numbers and with an overwhelming concentration of guns. Throughout the winter the Germans had accumulated vast stores of shells and other ammunition. It was impossible for Russia, with her restricted output, to compete with the enemy in this respect. Wherever the Austro-Germans attacked the Russian line with an appalling burst of shells the Grand Duke was obliged to retire.

But everywhere that retirement was conducted with calm deliberation, with calculated precision, and with a skill and coolness which has won for our Allies the profoundest admiration. They held position after position just so long as was necessary to cover the retiring troops, enabling them to evacuate their positions without loss of material or endangering the piercing of their line, the one thing the Germans sought and failed to achieve.

In this way the Russian rearguard held the enemy for fourteen days in check before they could enter Przemysl; so it was on the Grodek line, and so it was at Lemberg ; the enemy was held in every case until the Grand Duke had retired his main armies to safety.

Not until everything had been drawn into safety did the Grand Duke ever fall back so that the enemy could come on. There was never at any time disorder, panic, or confusion ; at every step great losses were inflicted on the enemy. Haste or confusion would have been fatal, the Russian forces would have lost touch, they would have been separated with certain disaster.

To the great skill, to the cool deliberation and courageous bravery of the Russians was due the defeat of the object of the Germans, namely, to destroy the cohesion of the Russian armies.

The Germans gained nothing except the ground previously lost, and that at enormous loss. The losses of the enemy were put at 600,000, and possibly they had spent their whole winter's accumulation of shells.

- pages from 'the War of the Nations' with scenes from Galicia in 1915

- texts from 'the War of the Nations' : see link for information on this magazine