With the English Hospital at Furnes, December 1914

and The British Field Hospital in Furnes for the story of the British Field Hospital in Furnes

I had a job to do on my first night in Furnes, and earned a dinner, for a change, by honest work. The staff of an English hospital with a mobile column attached to the Belgian cavalry for picking up the wounded on the field, had come into the town before dusk with a convoy of ambulances and motorcars. They established themselves in an old convent with large courtyards and many rooms, and they worked hurriedly as long as light would allow, and afterwards in darkness, to get things ready for their tasks next day, when many wounded were expected. This party of doctors and nurses, stretcher- bearers and chauffeurs, had done splendid work in Belgium.

Many of them were in the siege of Antwerp, where they stayed until the wounded had to be taken away in a hurry; and others, even more daring, had retreated from town to town, a few kilometres in advance of the hostile troops. I had met some of the party in Malo-les-Bains, where they had reassembled before coming to Furnes, and I had been puzzled by them. In the "flying column," as they called their convoy of ambulances, were several ladies very practically dressed in khaki coats and breeches, and very girlish in appearance and manners. They did not seem to me at first sight the type of woman to be useful on a battlefield or in a field-hospital. I should have expected them to faint at the sight of blood, and to swoon at the bursting of a shell. Some of them at least were too pretty, I thought, to play about in fields of war among men and horses smashed to pulp. It was only later that I saw their usefulness and marvelled at the spiritual courage of these young women, who seemed not only careless of shell-fire but almost unconscious of its menace, and who, with more nervous strength than that of many men, gave first-aid to the wounded without shuddering at sights of agony which might turn a strong man sick.

It is not an easy task to settle down into a new hospital, especially in time of war not far from the enemy's lines, and as a volunteer in the work I was able to make myself useful by lending a hand with mattresses and beds and heavy cases of medical material. It was a strange experience, as far as I was concerned, and sometimes seemed a little unreal as, with a bed on my head, I staggered across dark courtyards, or with my arms full of lint and dressings, I groped my way down the long, unlighted corridors of a Flemish convent. Nurses chivvied about with little squeals of laughter as they bumped into each other out of the shadow world, but not losing their heads or their hands, with so much work to do. Framed in one or other of the innumerable doorways stood a Belgian nun, with a white face, staring out upon those flitting shadows. The young doctors had flung their coats off and were handling the heaviest stuff like dock labourers at trade union rates, though with more agility. I made friends with them on the other side of cases too heavy for one man to handle - with a golden-haired, blue-eyed boy from Bart's (I think), who made the most preposterous jokes in the darkness, so that I laughed and nearly dropped my end of the box (I saw him in the days to come doing heroic and untiring work in the operating theatre), and with another young surgeon whose keen, grave face lighted up marvellously when an ironical smile caught fire in his brooding eyes, and with other men in this hospital and ambulance column who will be remembered in Belgium as fine and fearless men. With the superintendent of the commissariat department - an Italian lady with a pretty sense of humour and a devil-may-care courage which she inherited from Stuart ancestors - I went on a shopping expedition into the black gulfs of Furnes, stumbling into holes and jerking up against invisible gun-wagons, but bringing back triumphantly some fat bacon and, more precious still, some boxes of tallow candles, of great worth in a town which had lost its gas.

I lighted dozens of these candles, like an acolyte in a Catholic church, setting them in their own grease on windowsills and ledges of the long corridors, so that the work of moving might go on more steadily. But there was a wind blowing, and at the bang of distant doors out went one candle after another, and nurses carrying other candles and shielding the little flames with careful hands cried in laughing dismay as they were puffed out by malicious draughts.

There was chaos in the kitchen, but out of it came- order and a good meal, served in the convent refectory, where the flickering light of candles in beer-bottles sheltered from the wind, gleamed upon holy pictures of the Sacred Heart and the Madonna and Child and glinted upon a silver crucifix where the Man of Sorrows looked down upon a supper party of men and women who, whatever their creed or faith or unbelief, had dedicated themselves to relieve a suffering humanity with a Christian chivalry-which did not prevent the blue-eyed boy from making most pagan puns, or the company in general from laughing as though war were all a jest.

Having helped to wash up - the young surgeons fell into queue before the washtubs - I went out into the courtyard again. Horses were stabled there, guarded by a man who read a book by the rays of an old lantern, which was a little oasis of light in this desert of darkness. The horses were listening. Every now and then they jerked their heads up in a frightened way. From a few miles away came the boom of great guns, and the black sky quivered with tremulous bars of light as shell after shell burst somewhere over the heads of men waiting for death. With one of the doctors, two of the nurses, and a man who led the way, I climbed up to a high room in the convent roof. Through a dormer window we looked out across the flat country beyond Furnes and saw, a few miles away, the lines of battle. Some village was burning there, a steady torch under a heavy cloud of smoke made rosy and beautiful as a great flower over the scarlet flames. Shells were bursting with bouquets of light and then scattered stars into the sky. Short, sharp stabs revealed a Belgian battery, and very clearly we could hear the roll of field guns, followed by enormous concussions of heavy artillery.

"There will be work to do to-morrow !" said one of the nurses. Work came before it was expected in the morning Quite early some Belgian ambulances came up to the great gate of the convent loaded with wounded. A few beds were made ready for them and they were brought in by the stretcher-bearers and dressers. Some of them could stagger in alone, with the help of a strong arm, but others were at the point of death as they lay rigid on their stretchers, wet with blood. For the first time I felt the weight of a man who lies unconscious, and strained my stomach as I helped to carry these poor Belgian soldiers. And for the first time I had round my neck the arm of a man who finds each footstep a torturing effort, and who after a pace or two halts and groans, and loses the strength of his legs, so that all his weight hangs upon that clinging arm. Several times I nearly let these soldiers fall, so great was the burden weighing down my shoulders. It was only by a kind of prayer that I could hold them up and guide them to the great room where stretchers were laid out for lack of beds.

In a little while the great hall where I had helped to sort out packages was a hospital ward where doctors and nurses worked very quietly and from which there came faint groans of anguish, horrible in their significance. Already it was filled with that stench of blood and dirt and iodoform which afterwards used to sicken me as I helped to carry in i the wounded or carry out the dead. 8 In the courtyard the flying column was getting ready to set out in search of other wounded men, not yet rescued from the firing line. The officer in command was a young Belgian gentleman, Lieutenant de Broqueville, the son of the Belgian Prime Minister, and a man of knightly valour. He was arranging the order of the day with Dr. Munro, who had organized the ambulance convoy, leading it through a series of amazing adventures and misadventures-not yet to be written in history-to this halting-place at Furnes. Three ladies in field kit stood by their cars waiting for the day's commands, and there were four stretcher-bearers, of whom I was the newest recruit. Among them was an American journalist named Gleeson, who had put aside his pen for a while to do manual work in fields of agony, proving himself to be a man of calm and quiet courage, always ready to take great risks in order to bring in a stricken soldier. I came to know him as a good comrade, and in this page greet him again.

The story of the adventure which we went out to meet that day was written in the night that followed it, as I lay on straw with a candle by my side, and because it was written with the emotion of a great experience still thrilling in my brain and with its impressions undimmed by any later pictures of the war I will give it here again as it first appeared in the columns of the Daily Chronicle, suppressing only a name or two because those whom I wished to honour hated my publicity.

We set out before noon, winding our way through the streets of Furnes, which were still crowded with soldiers and wagons. In the Town Hall square we passed through a mass of people who surrounded a body of 150 German prisoners who had just been brought in from the front. It was a cheering sight for Belgians who had been so long in retreat before an overpowering enemy. It was a sign that the tide of fortune was changing. Presently we were out in open country, by the side of the Yser Canal. It seemed very peaceful and quiet. Even the guns were silent now, and the flat landscape, with its long, straight lines of poplars between the low-lying fields, had a spirit of tranquillity in the morning sunlight. It seemed impossible to believe. that only a few kilometres away great armies were ranged against each other in a death-struggle. But only for a little while. The spirit of war was forced upon our imagination by scenes upon the roadside. A squadron of Belgian cavalry rode by on tired horses. The men were dirty in the service of war, and haggard after long privations in the field. Yet they looked hard and resolute, and saluted us with smiles as we passed. Some of them shouted out a question : "Anglais ?" They seemed surprised and glad to see British ambulances on their way to the front. Belgian infantrymen trudged with slung rifles along the roads of the villages through which we passed. At one of our halts, while we waited for instructions from the Belgian headquarters, a group of these soldiers sat in the parlour of an inn singing a love-song in chorus. One young officer swayed up and down in a rhythmic dance, waving his cigarette. He had been wounded in the arm, and knew the horror of the trenches ; but for a little while he forgot, and was very gay because he was alive.

Our trouble was to know where to go. The fighting on the previous night had covered a wide area, but a good many of the wounded had been brought back. Where the wounded still lay the enemy's shell-fire was so heavy that the Belgian ambulances could get nowhere near. Lieutenant de Broqueville was earnestly requested not to lead his little column into unnecessary risks, especially as it was difficult to know the exact position of the enemy until reports came in from the field officers.

It was astonishing-as it is always in war-to find how soldiers quite near to the front are in utter ignorance of the course of a great battle. Many of the officers and men with whom we talked could not tell us where the allied forces were, nor where the enemy was in position, nor whether the heavy fighting during the last day and night had been to the advantage of the Allies or the Germans. They believed, but were not sure, that the enemy had been driven back many kilometres between Nieuport and Dixmude.

At last, after many discussions and many halts, we received our orders. We were asked to get into the town of Dixmude, where there were many wounded.

It was about sixteen kilometres away from Furnes, and about half that distance from where we had halted for lunch. Not very far away, it will be seen, yet as we went along the road, nearer to the sound of great guns which for the last hour or two had been firing incessantly again, we passed many women and children. It had only just occurred to them that death was round the corner and that there was no more security in those little stone or plaster houses of theirs, which in time of peace had been safe homes against all the evils of life. It had come to their knowledge, very slowly, that they were of no more protection than tissue paper under a rain of lead. So they were now leaving for a place at longer range. Poor old grandmothers in black bonnets and skirts trudged under the lines of poplars, with younger women who clasped their babes tight in one hand while with the other they carried heavy bundles. of household goods. They did not walk very fast. They did not seem very much afraid. They had a kind of patient misery in their look. Along the road came some more German prisoners, marching rapidly between mounted guards. Many of them were wounded, and all of them had a wild, famished, terror-stricken look. I caught the savage glare of their eyes as they stared into my car. There was something beast-like and terrible in their gaze like that of hunted animals caught in a trap.

At a turn in the road the battle lay before us, and we were in the zone of fire. Away across the fields was a line of villages, with the town of Dixmude a little to the right of us, perhaps two kilometres away. From each little town smoke was rising in separate columns, which met at the top in a great pall of smoke, as a heavy black cloud cresting above the light on the horizon line. At every moment this blackness was brightened by puffs of electric blue, extraordinarily vivid, as shells burst in the air. Then the colour gradually faded out, and the smoke darkened and became part of the pall. From the mass of houses in each town came jabs of flame, following the explosions which sounded with terrific, thudding shocks.

Upon a line of fifteen kilometres there was an incessant cannonade and in every town there was a hell. The furthest villages were already alight. I watched how the flames rose, and became great glowing furnaces. terribly beautiful. Quite close to us - only a kilometre away across the fields to the left - there were Belgian batteries at work, and rifle-fire from many trenches. We were between two fires, and the Belgian and German shells came screeching across our heads. The enemy's shells were dropping close to us, ploughing up the fields with great pits. We could hear them burst and scatter, and could see them burrow. In front of us on the road lay a dreadful barrier, which brought us to a halt. An enemy's shell had fallen right on top of an ammunition convoy. Four horses had been blown to pieces, and lay strewn across the road. The ammunition wagon had been broken into fragments, and smashed and burnt to cinders by the explosion of its own shells. A Belgian soldier lay dead, cut in half by a great fragment of steel. Further alone, the road were two other dead horses in pools of blood. It was a horrible and sickening sight from which one turned away shuddering with a cold sweat. But we had to pass after some of this dead flesh had been dragged away. Further down the road we had left two of the cars in charge of the three ladies. They were to wait there until we brought back some of the wounded, whom they would tak6 from us so that we could fetch some more out of Dixmude. The two ambulances came on with our light car, commanded by Lieutenant de Broqueville and Dr. Munro. Mr. Gleeson asked me to help him on the other end of his own stretcher.

I think I may say that none of us quite guessed what was in store for us. At least I did not guess that we had been asked to go into the open mouth of Death. I had only a vague idea that Dixmude would be just a little worse than the place at which we now halted for final instructions as to the geography of the town.

It was a place which made me feel suddenly cold, in spite of a little sweat which made my hands moist.

It was a halt between a group of cottages, where Belgian soldiers were huddled close to the walls under the timber beams of the barns. Several of the cottages were already smashed by shell-fire. There was a great gaping hole through one of the roofs. The roadway was strewn with bricks and plaster, and every now and then a group of men scattered as shrapnel bullets came pattering down. We were in an inferno of noise. It seemed as though we stood in the midst of the guns within sight of each other's muzzles. I was deafened and a little dazed, but very clear in the head, so that my thoughts seemed extraordinarily vivid. I was thinking, among other things, of how soon I should be struck by one of those flying bullets, like the men who lay moaning inside the doorway of one of the cottages. On a calculation of chances it could not be long.

The Belgian official in charge of this company was very courteous and smiling. It was only by a sudden catch of the breath between his words that one guessed at the excitement of his brain. He explained to us, at what seemed to me needless length, the case with which we could get into Dixmude, where there were many wounded. He drew a map of the streets, so that we could find the way to the II6tel de Ville, where some of them lay. We thanked him, and told the chauffeurs to move on. I was in one of the ambulances and Gleeson sat behind me in the narrow space between the stretchers. Over my shoulder he talked in a quiet voice of the job that lay before us. I was glad of that quiet voice, so placid in its courage.

We went forward at what seemed to me a crawl, though I think it was a fair pace. The shells were bursting round us now on all sides. Shrapnel bullets sprayed the earth about us. It appeared to me an odd thing that we were still alive.

Then we came into Dixmude. It was a fair-sized town, with many beautiful buildings, and fine old houses in the Flemish style - so I was told. When I saw it for the first time it was a place of death and horror. The streets through which we passed were utterly deserted and wrecked from end to end as though by an earthquake. Incessant explosions of shell-fire crashed down upon the walls which still stood. Great gashes opened in the walls, which then toppled and fell. A roof came tumbling down with an appalling clatter. Like a house of cards blown down by a puff of wind a little shop suddenly collapsed into a mass of ruins. Here and there, further into the town, we saw living figures. They ran swiftly for a moment and then disappeared into dark caverns under toppling porticoes. They were Belgian soldiers.

We were now in a side street leading into the Town Hall square. It seemed impossible to pass owing to the wreckage strewn across the road.

"Try to take it," said Dr. Munro, who was sitting beside the chauffeur.

We took it, bumping over the high débris, and then swept round into the square. It was a spacious place, with the Town Hall at one side of it, or what was left of the Town Hall. There was only the splendid shell of it left, sufficient for us to see the skeleton of a noble building which had once been the pride of Flemish craftsmen. Even as we turned towards it parts of it were falling upon the ruins already on the ground. I saw a great pillar lean forward and then topple down. A mass of masonry crashed down from the portico. Some still, dark forms lay among the fallen stones. They were dead soldiers. I hardly glanced at them, for we were in search of living men. The cars were brought to a halt outside the building and we all climbed down. I lighted a cigarette, and I noticed two of the other men fumble for matches for the same purpose. We wanted something to steady us.

There was never a moment when shell-fire was not bursting in that square about us. The shrapnel bullets whipped the stones. The enemy was making a target of the Hotel de Ville, and dropping their shells with dreadful exactitude on either side of it. I glanced towards a flaring furnace to the right of the building. There was a wonderful glow at the heart of it. Yet it did not give me any warmth at that moment.

Dr. Munro and Lieutenant de Broqueville mounted the steps of the Town Hall, followed by another brancardier and myself. Gleeson was already taking down a stretcher. He had a little smile about his lips.

A French officer and two men stood under the broken archway of the entrance between the fallen pillars and masonry. A yard away from them lay a dead soldier-a handsome young man with clear-cut features turned upwards to the gaping roof. A stream of blood was coagulating round his head, but did not touch the beauty of his face. Another dead man lay huddled up quite close, and his face was hidden.

“Are there any wounded here, sir ? " asked our young lieutenant.

The other officer spoke excitedly. He was a brave man, but could not hide the terror of his soul because he had been standing so long waiting for death which stood beside him but did not touch him. It appeared from his words that there were several wounded men among the dead, down in the cellar. He would be obliged to us if we could rescue them.

We stood on some steps looking down into that cellar. It was a dark hole-illumined dimly by a lantern, I think. I caught sight of a little heap of huddled bodies. Two soldiers still unwounded, dragged three of them out, handed them up, delivered them to us. The work of getting those three men into the first ambulance seemed to us interminable. It was really no more than fifteen to twenty minutes, while they were being arranged. During that time Dr. Munro was moving about the square in a dreamy sort of way, like a poet meditating on love or flowers in May. Lieutenant de Broqueville was making inquiries about other wounded in other houses. I lent a hand to one of the stretcher-bearers. What others were doing I don't know, except that Gleeson's calm face made a clear-cut image on my brain. I had lost consciousness of myself. Something outside myself, as it seemed, was talking now that there was no way of escape, that it was monstrous to suppose that all these bursting shells would not smash the ambulances to bits and finish the agony of the wounded, and that death is very hideous. I remember thinking also how ridiculous it is for men to kill each other like this, and to make such hells.

Then Lieutenant de Broqueville spoke a word of command. The first ambulance must now get back."

I was with the first ambulance, in Gleeson's company. We had a full load of wounded men-and we were loitering. I put my head outside the cover and gave the word to the chauffeur. As I did so a shrapnel bullet came past my head, and, striking a piece of ironwork, flattened out and fell at my feet. I picked it up and put it in my pocket-though God alone knows why, for I was not in search of souvenirs. So we started with the first ambulance, through those frightful streets again, and out into the road to the country.

"Very hot," said one of the men. I think it was 'the chauffeur. Somebody else asked if we should get through with luck.

Nobody answered the question. The wounded men with us were very quiet. I thought they were dead. There was only the incessant cannonade and the crashing of buildings. Mitrailleuses were at work now spitting out bullets. It was a worse sound than the shells. It seemed more deadly in its rattle. I stared back behind the car and saw the other ambulance in our wake. I did not see the motor-car. Along the country road the fields were still being ploughed by shell, which burst over our heads. We came to a halt again at the place where the soldiers were crouched under the cottage walls. There were few walls now, and inside some of the remaining cottages many wounded men. Their own comrades were giving them first aid, and wiping the blood out of their eyes. We managed to take some of these on board. They were less quiet than the others we had, and groaned in a heartrending way.

And then, a little later, we made a painful discovery. Lieutenant de Broqueville, our gallant young leader, was missing. By some horrible mischance he had not taken his place in either of the ambulances or the motor-car. None of us had the least idea what had happened to him. We had all imagined that he had scrambled up like the rest of us, after giving the order to get away. We looked at each other in dismay. There was only one thing to do, to get back in search of him. Even in the half-hour since we had left the town Dixmude had burst into flames and was a great blazing torch. If young de Broqueville were left in that furnace he would not have a chance of life.

It was Gleeson and another stretcher-bearer who with great gallantry volunteered to go back and search for our leader. They took the light car and sped back towards the burning town.

The ambulances went on with their cargo of wounded, and I was left in a car with one of the ladies while Dr. Munro was ministering to a man on the point of death. It was the girl whom I had seen on the lawn of an old English house in the days before the war. She was very worried about the fate of de Broqueville, and anxious beyond words as to what would befall the three friends who were now missing. We drove back along the road towards Dixmude, and rescued another wounded man left in a wayside cottage. By this time there were five towns blazing in the darkness, and in spite of the awful suspense which we were now suffering, we could not help staring at the fiendish splendour of that sight. Dr. Munro joined us again, and after a consultation we decided to get as near Dixinude as we could, in case our friends had to come out without their car or wounded.

The enemy's bombardment was now terrific. All its guns were concentrated upon Dixinude and the surrounding trenches. In the darkness close under a stable wall I stood listening to the great crashes for an hour, when I had not expected such a grace of life. Inside the stable, soldiers were sleeping in the straw, careless that any moment a shell might burst through upon them and give them unwaking sleep. The hour seemed a night. Then we saw the gleam of headlights, and an English voice called out.

Our two friends had come back. They had gone to the entry of Dixinude, but could get no further owing to the flames and shells. They, too, had waited for an hour, but had not found de Broqueville. It seemed certain that he was dead, and very sorrowfully, as there was nothing to be done, we drove back to Furnes.

At the gate of the convent were some Belgian ambulances which had come from another part of the front with their wounded. I helped to carry one of them in, and strained my shoulders with the weight of the stretcher. Another wounded man put his arm round my neck, and then, with a dreadful cry, collapsed, so that I had to hold him in a strong grip. A third man, horribly smashed about the head, walked almost unaided into the operating-room. Gleeson and I led him. with just a touch on his arm. Next morning he lay dead on a little pile of straw in a quiet corner of the courtyard.

I sat down to a supper which I had not expected to eat. There was a strange excitement in my body, which trembled a little after the day's adventures. It seemed very strange to be sitting down to table with cheerful faces about me. But some of the faces were not cheerful. Those of us who knew of the disappearance of de Broqueville sat silently over our soup. Then suddenly there was a sharp exclamation of surprise -of sheer amazement-and Lieutenant de Broqueville came walking briskly forward, alive and well. . . . It seemed a miracle.

It was hardly less than that. For several hours after our departure from Dixinude he had remained in that inferno. He had missed us when he went down into the cellars to haul out another wounded man, forgetting that he had given us the order to start. There he had remained with the buildings crashing all around him until the. enemy's fire had died down a little. He succeeded in rescuing his wounded, for whom he found room in a Belgian ambulance outside the town, and walked back along the road to Furnes. So we gripped his hands and were thankful for his escape.

Early next morning I went into Dixmude again with some of the men belonging to the " flying column." It was more than probable that there were still a number of wounded men there, if any of them were left alive after that night of horror when they lay in cellars or under the poor shelter of broken walls. Perhaps also there were men but lately wounded, for before the dawn had come some of the Belgian infantry had been sent into the outlying streets with mitrailleuses, and on the opposite side German infantry were in possession of other streets or of other ruins, so that bullets were ripping across the mangled town. The artillery was fairly quiet. Only a few shells were bursting over the Belgian lines-enough to keep the air rumbling with irregular thunderclaps. But as we approached the corner where we had waited for news of de Broqueville one of these shells burst very close to us and ploughed up a big hole in a field across the roadside ditch. We drove more swiftly with empty cars and came into the streets of Dixrnude. They were sheets of fire, burning without flame but with a steady glow of embers. They were but cracked shells of houses, unroofed and swept clean of their floors and furniture, so that all but the bare walls and a few charred beams had been consumed by the devouring appetite of fire. Now and again one of the beams broke and fell with a crash into the glowing heart of the furnace, which had once been a Flemish house, raising a fountain of sparks. Further into the town, however, there stood, by the odd freakishness of an artillery bombardment, complete houses hardly touched by shells and, very neat and prim, between masses of shapeless ruins. One street into which I drove was so undamaged that I could hardly believe my eyes, having looked back the night before to one great torch which men called " Dixmude." Nevertheless some of its window-frames had bulged with heat, and panes of glass fell with a splintering noise on to the stone pavement. As I passed a hail of shrapnel was suddenly flung upon the wall on one side of the street and the bullets played at marbles in the roadway. In this street some soldiers were grouped about two wounded men, one of them only lightly touched, the other - a French marine - at the point of death, lying very still in a huddled way with a clay-coloured face smeared with blood. We picked them up and put them into one of the ambulances, the dying man groaning a little as we strapped him on the stretcher.

The Belgian soldiers who had come into the town at dawn stood about our ambulances as though our company gave them a little comfort. They did not speak much, but had grave wistful eyes like men tired of all this misery about them but unable to escape from it. They were young men with a stubble of fair hair on their faces and many days' dirt.

"Vous etes tres aimable," said one of them when I banded him a cigarette, which he took with a trembling hand. Then he stared up the street as another shower of shrapnel swept it, and said in a hasty way, " C’est I'enfer. . . . Pour trois mois je reste sous feu. Cest trop, n'est-ce pas ? "

But there was no time for conversation about war and the effects of war upon the souls of men. The German guns were beginning to speak again, and unless we made haste we might not rescue the wounded men.

"Are there many blessés here ? " asked our leader.

One of the soldiers pointed to a house which had a tavern sign above it.

"They've been taken inside." he said. " I helped to carry them." We dodged the litter in the roadway, where, to my amazement, two old ladies were searching in the rubbish-heaps for the relies of their houses. They had stayed in Dixmude during this terrible bombardment, hidden in some cellar, and now had emerged, in their respectable black gowns, to see what damage had been done. They seemed to be looking for something in particular - some little object not easy to find among these heaps of calcined stones and twisted bars of iron. One old woman shook her head sadly as though to say, "Dear me, I can't see it anywhere." I wondered if they were looking for some family photograph or for some child's cinders. It might have been one or the other, for many of these Belgian peasants had reached a point of tragedy when death is of no more importance than any trivial loss. The earth and sky had opened, swallowing up all their little world in a devilish destruction. They had lost the proportions of everyday life in the madness of things.

In the tavern there was a Belgian doctor with a few soldiers to help him, and a dozen wounded in the straw which had been put down on the tiled floor. Another wounded man was sitting on a chair, and the doctor was bandaging up a leg which looked like a piece of raw meat at which dogs had been gnawing. Something in the straw moved and gave a frightful groan. A boy soldier with his back propped against the wall had his knees up to his chin and his face in his grimy hands through which tears trickled. There was a soppy bandage about his head. Two men close to where I stood lay stiff and stark, as though quite dead, but when I bent down to them I heard their hard breathing and the snuffle of their nostrils. The others more lightly wounded watched us like animals, without curiosity but with a horrible sort of patience in their eyes, which seemed to say, " Nothing matters. . . . Neither hunger nor thirst nor pain. We are living but our spirit is dead."

The doctor did not want us to take away his wounded at once. The German shells were coming heavily again, on the outskirts of the town through which we had to pass on our' way out. An officer had just come in to say they were firing at the level crossing to prevent the Belgian ambulances from coming through. It would be better to wait a while before going back again. It was foolish to take unnecessary risks.

I, admit frankly that I was anxious to go as quickly as possible with these wounded A shell burst over the houses on the opposite side of the street. When I stood outside watching two soldiers who had been sent further down to bring in two other wounded men who lay in a house there, I saw them dodge into a doorway for cover as another hail of shrapnel whipped the stones about them. Afterwards they made an erratic course down the street like drunken men, and presently I saw them staggering back again with their wounded comrades, who had their arms about the necks of their rescuers. . . . I went out to aid them, but did not like the psychology of this street, where death was teasing the footsteps of men, yapping at their heels.

1 helped to pack up one of the ambulances and went back to Furnes sitting next to the driver, but twisted round so that I could hold one of the stretcher poles which wanted to jolt out of its strap so that the man lying with a dead weight on the canvas would come down with a smash upon the body of the man beneath.

Ca y est, " said my driver friend, very cheerfully. He was a gentleman volunteer with his own ambulance and looked like a seafaring man in his round yachting cap and blue jersey. He did not speak much French, I fancy, but I loved to hear him say that 'Ca y est, ', when he raised a stretcher in his hefty arms and 'packed a piece of bleeding flesh into the top of his car with infinite care lest he should give a jolt to broken bones.

One of the men behind us had his leg smashed in two places. As we went over roads with great stones and the rubbish of ruined houses he cried out again and again in a voice of anguish:

"Pas si vite I Pour l’amour de Dieu. . . . Pas si vite !”

Not so quickly. But when we came out of the burnt streets towards the level crossing of the railway it seemed best to go quickly. Shells were falling in the fields quite close to us. One of them dug a deep hole in the road twenty yards ,ahead of us. Another burst close behind. Instinctively I yearned for speed. I wanted to rush along that road and get beyond the range of fire. But the driver in the blue jersey, hearing that awful cry behind him, slowed down and crawled along.

"Poor devil," he said. "I can imagine what it feels like when two bits of broken bone get rubbing together. Every jolt and jar must give him hell."

He went slower still, at a funeral pace, and looking back into the ambulance said " Ca y est, mon vieux. . . . Bon courage

Afterwards, this very gallant gentleman was wounded himself, and lay in one of the ambulances which he had often led towards adventure, with a jagged piece of steel in his leg, and two bones rasping together at every jolt. But when he was lifted up, he stifled a groan and gave his old cheerful cry of "Ca y est !”

During the two days that followed the convent at Furnes was overcrowded with the wounded. All day long and late into the night they were brought back by the Belgian ambulances from the zone of fire, and hardly an hour passed without a bang at the great wooden gates in the courtyard which were flung open to let in another tide of human wreckage.

The Belgians were still holding their last remaining ground-it did not amount to more than a few fields and villages between the French frontier and Dixmude - with a gallant resistance which belongs without question to the heroic things of history. During these late days in October, still fighting almost alone, for there were. no British soldiers to help them and only a few French batteries with two regiments of French marines, they regained some of their soil and beat back the enemy from positions to which it had advanced. In spite of the most formidable attacks made by the German troops along the coastline between Westende and Ostende, and in a crescent sweeping round Dixmude for about thirty kilometres, those Belgian soldiers, tired out by months of fighting with decimated regiments and with but the poor remnant of a disorganized army, not only stood firm, but inflicted heavy losses upon the enemy and captured four hundred prisoners. For a few hours the Germans succeeded in crossing the Yser, threatening a general advance upon the Belgian line. Before Nieuport their trenches were only fifty metres away from those of the Belgians, and on the night of October 22 they charged eight times with the bayonet in order to force their way through.

Each assault failed against the Belgian infantry, who stayed in their trenches in spite of the blood that eddied about their feet and the corpses that lay around them. Living and dead made a rampart which the Germans could not break. With an incessant rattle of mitraillcuses and rifle-fire, the Belgians mowed down the German troops as they advanced in solid ranks, so that on each of those eight times the enemy's attack was broken and destroyed. They fell like the leaves which were then being scattered by the autumn wind and their bodies were strewn between the trenches. Some of them were the bodies of very young men-poor boys of sixteen and seventeen from German high schools and universities who were the sons of noble and well-to-do families, had been accepted as volunteers by Prussian war-lords ruthless of human life in their desperate gamble with fate. Some of these lads were brought to the hospitals in Furnes, badly wounded. One of them carried into the convent courtyard smiled as he lay on his stretcher and spoke imperfect French very politely to Englishwomen who bent over him, piteous as girls who see a wounded bird. He seemed glad to be let off slightly with only a wound in his foot which would make him limp for life ; very glad to be out of all the horror of those trenches on the German side of the Yser. One could hardly call this boy an ‘enemy’. He was just a poor innocent caught up by a devilish power, and dropped when of no more use as an instrument of death. The pity that stirs one in the presence of one of these broken creatures does not come to one on the field of battle, where there is no single individuality, but only a grim conflict of unseen powers, as inhuman as thunderbolts, or as the destructive terror of the old nature gods. The enemy, then, fills one with a hatred based on fear. One rejoices to see a shell burst over his batteries and is glad at the thought of the death that came to him of that puff of smoke. But I found that no such animosity stirs one in the presence of the individual enemy or among crowds of their prisoners. One only wonders at the frightfulness of the crime which makes men kill each other without a purpose of their own, but at the dictate of powers far removed from their own knowledge and interests in life.

That courtyard in the convent at Furnes will always haunt my mind as the scene of a grim drama. Sometimes, standing there alone, in the darkness, by the side of an ambulance, I used to look up at the stars and wonder what God might think of all this work if there were any truth in old faiths. A pretty mess we mortals made of life. ! might almost have laughed at the irony of it all, except that my laughter would have choked in my throat and turned e sick. They were beasts, and worse than beasts, to maim and mutilate each other like this, having no real hatred in their hearts for each other, but only a stupid perplexity that they should be hurled in masses against each other's ranks, to slash and shoot and burn in obedience to orders by people who were their greatest enemies-Ministers of State, with cold and calculating brains, high inhuman officers who studied battlefields as greater chessboards. So ! - a little black ant in a shadow on the earth under the eternal sky - used to think like this, and to stop thinking these silly irritating thoughts turned to the job in hand, which generally was to take up one end of a stretcher laden with a bloody man, or to give my shoulder to a tall soldier who leaned upon it and stumbled forward to an open door which led to the operating-table and an empty bed, where he might die if his luck were out.

The courtyard was always full of stir and bustle in the hours when the ambulance convoys came in with their cargoes of men rescued from the firing zone. The headlights of the cars thrust shafts of blinding light into the darkness as they steered round in the steep and narrow road which led to the convent gates between two high thick walls, and then, with a grinding and panting, came inside to halt beside cars already at a standstill. The cockney voices of the chauffeurs called to each other.

“Blast yer, Bill . . . Carn't yer give a bit of elber room ? Gord almighty, 'ow d'yer think I can get in there ? "

Women came out into the yard, their white caps touched by the light of their lanterns, and women's voices spoke quietly.

" Have you got many this time ? .. . . . .. We can hardly find an inch of room." . "It's awful having to use stretchers for beds. "There were six deaths this afternoon."

Then would follow a silence or a whispering of stretcher-bearers, telling their adventures to a girl in khaki breeches, standing with one hand in her jacket pocket, and with the little flare of a cigarette glowing upon her cheek and hair.

" All safe ? . . . That was luck ! "

"O mon Dieu ! Sacrénom ! 0 ! 0 !"

It was a man's voice crying in agony, rising to a shuddering, bloodcurdling scream: "0 Jésus !'

One could not deafen one's ears against that note of human agony. It pierced into one's soul. One could only stand gripping one's hands in this torture chamber, with darkness between high walls, and with shadows making awful noises out of the gulfs of blackness.

The cries of the wounded men died down and whimpered out into a dull faint moaning.

A laugh came chuckling behind an ambulance.

"Hot ? . I should think it was ! But we picked the men up and crossed the bridge all right. . . . The shells were falling on every side of us. . . . I was pretty scared, you bet. . . . It's a bit too thick, you know ! "

Silence again. Then a voice speaking quietly across the yard :

"Anyone to lend a hand ? There's a body to be carried out."

I helped to carry out the body, as every one helped to do any small work if he had his hands free at the moment. It was the saving of one's sanity and self-respect. Yet to me, more sensitive perhaps than it is good to be, it was a moral test almost greater than my strength of will to enter that large room where the wounded lay, and to approach a dead man through a lane of dying. (So many of them died after a night in our guest-house. Not all the skill of surgeons could patch up some of those bodies, torn open with ghastly wounds from German shells.) The smell of wet and muddy clothes, coagulated blood and gangrened limbs, of iodine and chloroform, sickness and sweat of agony, made a stench which struck one's senses with a foul blow. I used to try and close my nostrils to it, holding my breath lest I should vomit. I used to try to keep my eyes upon the ground, to avoid the sight of those smashed faces, and blinded eyes, and tattered bodies, lying each side of me in the hospital cots, or in the stretchers set upon the floor between them. I tried to shut my eyes to the sounds in this room, the hideous snuffle of men drawing their last breaths, the long-drawn moans of men in devilish pain, the ravings of fever-stricken men crying like little children -" Maman I O Maman !"--or repeating over and over again some angry protest against a distant comrade.

But sights and sounds and smells forced themselves upon one's senses. I had to look and to listen and to breathe in the odour of death and corruption. For hours afterwards I would be haunted with the death face of some young man, lying half-naked on his bed while nurses dressed his horrible wounds. What waste of men I What disfigurement of the beauty that belongs to youth ! Bearded soldier faces lay here in a tranquillity that told of coming death. They had been such strong and sturdy men, tilling their Flemish fields, and living with a quiet faith in their hearts. Now they were dying before their time, conscious, some of them, that death was near, so that weak tears dropped upon their beards, and in their eyes was a great fear and anguish.

"Je ne veux pas mourir I " said one of them. "O ma pauvre femme I Je ne veux pas mourir.”

He did not wish to die but in the morning he was dead.

The corpse that I had to carry out lay pinned up in a sheet. The work had been very neatly done by the nurse. She whispered to me as I stood on one side of the bed, with a friend on the other side.

"Be careful. . . . , He might fall in half."

I thought over these words as I put my hands under the warm body and helped to lift its weight on to the stretcher. Yes, some of the shell wounds were rather big. One could hardly sew a man together again with bits of cotton. . . . It was only afterwards, when I had helped to put the stretcher in a separate room on the other side of the courtyard, that a curious trembling took possession of me for a moment. . . . The horror of it all I . . . Were the virtues which were supposed to come from war, "the binding strength of nations," "the cleansing of corruption," all the falsities of men who make excuses for this monstrous crime, worth the price that was being paid in pain and tears and death ? It is only the people who sit at home who write these things. When one is in the midst of war false heroics are blown out of one's soul by all its din and tumult of human agony. One learns that courage itself exists, in most cases, as the pride in the heart of men very much afraid - a pride which makes them hide their fear. They do not become more virtuous in war, but only reveal the virtue that is in them. The most heroic courage which came into the courtyard at Furnes was not that of the stretcher-bearers who went out under fire, but that of the doctors and nurses who tended the wounded, toiling ceaselessly in the muck of blood, amidst all those sights and sounds. My spirit bowed before them as I watched them at work. I was proud if I could carry soup to any of them when they came into the refectory for a hurried meal, or if I could wash a plate clean so that they might fill it with a piece of meat from the kitchen stew. I would have cleaned their boots for them if it had been worth while cleaning boots to tramp the filthy yard.

"It's not surgery!" said one of the young surgeons, coming out of the operating-theatre and washing his hands at the kitchen sink ; " it's butchery ! "

He told me that he had never seen such wounds or imagined them, and as for the conditions in which he worked -he raised his hands and laughed at the awfulness of them, because it is best to laugh when there is no remedy. There was a scarcity of dressings, of instruments, of sterilizers. The place was so crowded that there was hardly room to turn, and wounded men poured in so fast that it was nothing but hacking and sewing.

"I'm used to blood," said the young surgeon. "It's some years now since I was put through my first ordeal, of dissecting dead bodies and then handling living tissue. You know how it's done - by gradual stages until a student no longer wants to faint at the sight of raw flesh, but regards it as so much material for scientific work. But this I " - he looked towards the room into which the wounded came - It's getting on my nerves a little. It's the sense of wanton destruction that makes one loathe it, the utter senselessness of it all, the waste of such good stuff. War is a hellish game and I'm so sorry for all the poor Belgians who are getting it in the neck. They didn't ask for it ! "

The wooden gates opened to let in another ambulance full of Belgian wounded, and the young surgeon nodded to me with a smile.

Another little lot ! I must get back into the slaughterhouse. So long!"

I helped out one of the " sitting-up " cases-a young man with a wound in his chest, who put his arm about my neck and said, " Merci ! Merci ! " with a fine courtesy, until suddenly he went limp, so that I had to hold him with all my strength, while he vomited blood down my coat. I had to get help to carry him indoors.

And yet there was laughter in the convent where so many men lay wounded. It was only by gaiety and the quick capture of any jest that those doctors and nurses and ambulance girls could keep their nerves steady. So in the refectory, when they sat down for a meal, there was an endless fire of raillery, and the blue-eyed boy with the blond hair used to crow like Peter Pan and speak a wonderful mixture of French and English, and play the jester gallantly. There would be processions of plate-bearers to the kitchen next door, where a splendid Englishwoman - one of those fine square-faced, brown-eyed, cheerful souls - had been toiling all day in the heat of oven and stoves to cook enough food for fifty-five hungry people who could not wait for their meals. There was a scramble between two doctors for the last potatoes, and a duel between one of them and myself in the slicing up of roast beef or boiled mutton, and amorous advances to the lady cook for a tit-bit in the baking-pan. There never was such - kitchen, and a County Council inspector would have reported on it in lurid terms. The sink was used as a wash-place by surgeons, chauffeurs, and stretcher-bearers. Nurses would come through with bloody rags from the ward, which was only an open door away. Lightly wounded men, covered with Yser mud, would sit at a side table, eating the remnants of other people's meals. Above the sizzling of sausages and the clatter of plates one could hear the moaning of the wounded and the incessant monologue of the fever-stricken. And yet it is curious I look back upon that convent kitchen as a place of gaiety, holding many memories of comradeship, and as a little sanctuary from the misery of war. I was a scullion in it, at odd hours of the day and night when I was not following the ambulance wagons to the field, or helping to clean the courtyard or doing queer little jobs which some one had to do. "I want you to dig a hole and help me to bury an arm," said one of the nurses. " Do you mind? "

1 spent another hour helping a lady to hang up blankets, not very well washed, because they were still stained with blood, and not very sanitary, because the line was above a pile of straw upon which men had died. There were many rubbish heaps in the courtyard near which it was not wise to linger, and always propped against the walls were stretchers soppy with blood, or with great dark stains upon them where blood had dried. It was like the courtyard of a shambles, this old convent enclosure, and indeed it was exactly that, except that the animals were not killed outright, but lingered in their pain.

Early each morning the ambulances started on their way to the zone of fire, where always one might go gleaning in the harvest fields of war. The direction was given us, with the password of the day, by young de Broqueville, who received the latest reports from the Belgian headquarters staff. As a rule there was not much choice. It lay somewhere between the roads to Nieuport on the coast, and inland, to Pervyse, Dixmude, St. Georges, or Ramscapelle where the Belgian and German lines formed a crescent down to Ypres.

The centre of that half-circle girdled by the guns was an astounding and terrible panorama., traced in its outline by the black fumes of shell-fire above the stabbing flashes of the batteries. Over Nieuport there was a canopy of smoke, intensely black, but broken every moment by blue glares of light as a shell burst and rent the blackness. Villages were burning on many points of the crescent, some of them smouldering drowsily, others blazing fiercely like beacon fires.

Dixmude was still alight at either end, but the fires seemed to have burnt down at its centre. Beyond, on the other horn of the crescent, were five flaming torches, which marked what were once the neat little villages of a happy Belgium. It was in the centre of this battleground, and the roads about me had been churned up by shells and strewn with shrapnel bullets. Close to me in a field, under the cover of a little wood, were some Belgian batteries. They were firing with a machine-like regularity, and every minute came the heavy bark of the gun, followed by the swish of the shell, as it flew in a high are and then smashed over the German lines. It was curious to calculate the length of time between the flash and the explosion. Further away some naval guns belonging to the French marines were getting the range of the enemy's positions, and they gave a new note of music to this infernal orchestra. It was a deep, sullen crash, with a tremendous menace in its tone. The enemy's shells were bursting incessantly, and at very close range, so that at times they seemed only a few yards away. The Germans had many great howitzers, and the burst of the shell was followed by enormous clouds which hung heavily in the air for ten minutes or more. It was these shells which dug great holes in the ground deep enough for a cart to be buried. Their moral effect was awful, and one's soul was a shuddering coward before them. The roads were encumbered with long convoys of provisions for the troops, ambulances, Red Cross motor-cars, gun-wagons, and farm carts. Two regiments of Belgian cavalry - the chasseurs a cheval - were dismounted and bivouacked with their horses drawn up in single line along the roadway for half a mile or more. The men were splendid fellows, hardened by the long campaign, and amazingly careless of shells. They wore a variety of uniforms, for they were but the gathered remnants of the Belgian cavalry division which. had fought from the beginning of the war. I was surprised to see their horses in such good condition, in spite of a long ordeal which had so steadied their nerves that they paid not the slightest heed to the turmoil of the guns.

Near the line of battle, through outlying villages and past broken farms, companies of Belgian infantry were huddled under cover out of the way of shrapnel bullets if they could get the shelter of a doorway or the safer side of a brick wall. I stared into their faces and saw how dead they looked. It seemed as if their vital spark had already been put out by the storm of battle. Their eyes were sunken and quite expressionless. For week after week, night after night, they had been exposed to shell-fire, and something had died within them-perhaps the desire to live. Every now and then some of them would duck their heads as a shell burst within fifty or a hundred yards of them, and I saw then that fear could still live in the hearts of men who had become accustomed to the constant chance of death. For fear exists with the highest valour, and its psychological effect is not unknown to heroes who have the courage to confess the truth.

If any man says he is not afraid of shell-fire," said one of the bravest men I have ever met--and. at that moment we were watching how the enemy's shrapnel was ploughing up the earth on either side of the road on which we stood" he is a liar I " There are very few men in this war who make any such pretence. On the contrary, most of the French, Belgian, and English soldiers with whom I have had wayside conversations since the war began, find a kind of painful pleasure in the candid confession of their fears.

"It is now three days since I have been frightened," said a young English officer, who, I fancy, was never scared in his life before he came out to see these battlefields of terror.

"I was paralysed with a cold and horrible fear when I was ordered to advance with my men over open ground under the enemy's shrapnel," said a French officer with the steady brown eyes of a man who in ordinary tests of courage would smile at the risk of death.

But this shell-fire is not an ordinary test of courage. Courage is annihilated in the face of it. Something else takes its place - a philosophy of fatalism, sometimes an utter boredom with the way in which death plays the fool with men, threatening but failing to kill ; in most cases a strange extinction of all emotions and sensations, so that men who have been long under shell-fire have a peculiar rigidity of the nervous system, as if something has been killed inside them. though outwardly they are still alive and untouched.

The old style of courage, when man had pride and confidence in his own strength and valour against other men, when he was on an equality with his enemy in arms and intelligence, has almost gone. It has quite gone when he is called upon to advance or hold the ground in face of the enemy's artillery. For all human qualities are of no avail against those death-machines. What are quickness of wit, the strength of a man's right arm, the heroic fibre of his heart, his cunning in warfare, when he is opposed by an enemy's batteries which belch out bursting shells with frightful precision and regularity ? What is the most courageous man to do in such an hour ? Can he stand erect and fearless under a sky which is raining down jagged pieces of steel ? Can he adopt the pose of an Adelphi hero, with a scornful smile on his lips, when a yard away from him a hole large enough to bury a taxicab is torn out of the earth, and when the building against which he has been standing is suddenly knocked into a ridiculous ruin ?

It is impossible to exaggerate the monstrous horror of the shell-fire, as I knew when I stood in the midst of it, watching its effect upon the men around me, and analysing my own psychological sensations with a morbid interest. I was very much afraid - day after day I faced that music and hated it - but there were all sorts of other sensations besides fear which worked a change in me. I was conscious of great physical discomfort which reacted upon my brain. The noises were even more distressing to me than the risk of death. It was terrifying in its tumult. The German batteries were hard at work round Nieuport, Diximide, Pervyse, and other towns and villages, forming a crescent, with its left curve sweeping away from the coast. One could see the stabbing flashes from some of the enemy's guns and a loud and unceasing roar came from them with regular rolls of thunderous noise interrupted by sudden and terrific shocks, which shattered into one's brain and shook one's body with a kind of disintegrating tumult. High above this deep-toned concussion came the cry of the shells-that long carrying buzz-like a monstrous, angry bee rushing away from a burning hive-which rises into a shrill singing note before ending and bursting into the final boom which scatters death. But more awful was the noise of our own guns. At Nieuport I stood only a few hundred yards away from the warships lying off. the coast. Each shell which they sent across the dunes was like one of Jove's thunderbolts, and made one's body and soul quake with the agony of its noise. The vibration was so great that it made my skull ache as though it had been hammered. Long afterwards I found myself trembling with those waves of vibrating sounds. Worse still, because sharper and more piercingly staccato, was my experience close to a battery of French cent-vingt. Each shell was fired with a hard metallic crack, which seemed to knock a hole into my ear-drums. I suffered intolerably from the noise, yet - so easy it is to laugh in the midst of pain - he laughed aloud when a friend of mine, passing the battery in his motor-car, raised his hand to one of the gunners, and said, "Un moment, s'il vous plait I " It was like asking Jove to stop his thunderbolts.

Some people get accustomed to the noise, but others never. Every time a battery fired simultaneously one of the men who were with me, a hard .. tough type of mechanic, shrank and ducked his head with an expression of agonized horror. He confessed to me that it " knocked his nerves to pieces. " Three such men out of six or seven had to be invalided home in one week. One of them had a crise de nerfs, which nearly killed him. Yet it was not fear which was the matter with them. Intellectually they were brave men and coerced themselves into joining many perilous adventures. It was the intolerable strain upon the nervous system that made wrecks of them. Some men are attacked with a kind of madness in the presence of shells. It is what a French friend of mine called la folie des obus. It is a kind of spiritual exultation which makes them lose self-consciousness and be caught up, as it were, in the delirium of those crashing, screaming things. In the hottest quarter of an hour in Dixmude one of. my friends paced about aimlessly with a dreamy look in his eyes. I am sure he had not the slightest idea where he was or what he was doing. I believe he was "outside himself," to use a good old-fashioned phrase. And at Antwerp, when a convoy of British ambulances escaped with their wounded through a storm of shells, one man who had shown a strange hankering for the heart of the inferno, stepped off his car, and said : " I must go back, I must go back! Those shells call to me." He went back and has never been heard of again.

Greater than one's fear. more overmastering in one's interest is this shell-fire. It is frightfully interesting to watch the shrapnel bursting near bodies of troops, to see the shells kicking up the earth, now in this direction and now in that ; to study a great building gradually losing its shape and falling into ruins ; to see how death takes its toll in an indiscriminate way - smashing a human being into pulp a few yards away and leaving oneself alive, or scattering a roadway with bits of raw flesh which a moment ago was a team of horses, or whipping the stones about a farmhouse with shrapnel bullets which spit about the crouching figures of soldiers who stare at these pellets out of sunken eyes. One's interest holds one in the firing zone with a grip from which one's intelligence cannot escape whatever may be one's cowardice. It is the most satisfying thrill of horror in the world. How foolish this death is I How it picks and chooses, taking a man here and leaving a man there by just a hair's-breadth of difference. It is like looking into hell and watching the fury of supernatural forces at play with human bodies, tearing them to pieces with great splinters of steel and burning them in the furnace-fires of shell-stricken towns, and in a devilish way obliterating the image of humanity in a welter of blood.

There is a beauty in it too. Beautiful and terrible were the fires of those Belgian towns which I watched under a star-strewn sky. There was a pure golden glow, as of liquid metal, beneath the smoke columns and the leaping tongues of flame. And many colours were used to paint this picture of war, for the enemy used shells with different coloured fumes, by which I was told they studied the effect of their fire. Most vivid is the ordinary shrapnel, which tears a rent through the black volumes of smoke rolling over a smouldering town with a luminous sphere of electric blue. Then from the heavier guns come dense puff-balls of tawny orange, violet, and heliotrope, followed by fleecy little cumuli of purest white. One's mind is absorbed in this pageant of shell-fire, and with a curious intentness, with that rigidity of nervous and muscular force which I have described, one watches the zone of fire sweeping nearer to oneself, bursting quite close, killing people not very far away.

Men who have been in the trenches under heavy shell-fire, sometimes for as long as three days, come out of their torment like men who have been buried alive. They have the brownish, ashen colour of death. They tremble as through anguish. They are dazed and stupid for a time. But they go back. That is the marvel of it. They go back day after day, as the Belgians went day after day. There is no fun in it, no sport, none of that heroic adventure which used perhaps-gods know - to belong to warfare when men were matched against men, and not against unapproachable artillery. This is their courage, stronger than all their fear. There is something in us, even divine pride of manhood, a dogged disregard of death, though it comes from an unseen enemy out of a smoke-wracked sky, like the thunderbolts of the gods, which makes us go back, though we know the terror of it. For honour's sake men face again the music of that infernal orchestra, and listen with a deadly sickness in their hearts to the song of the shell screaming the French word for kill, which is tue ! tue !

It was at night that I used to see the full splendour of the war's infernal beauty. After a long day in the fields travelling back in the repeated journeys to the station of Fortem, where the lightly wounded men used to be put on a steam tramway for transport to the Belgian hospitals, the ambulances would gather their last load and go homeward to Furnes. It was quite dark then, and towards nine o'clock the enemy's artillery would slacken fire, only the heavy guns sending out long-range shots. But five towns or more were blazing fiercely in the girdle of fire, and the sky throbbed with the crimson glare of their furnaces, and tall trees to which the autumn foliage clung would be touched with light, so that their straight trunks along a distant highway stood like ghostly sentinels. Now and again, above one of the burning towns a shell would burst as though the enemy were not content with their fires and would smash them into smaller fuel.

As I watched the flames, I knew that each one of those poor burning towns was the ruin of something more than bricks and mortar. It was the ruin of a people's ideals, fulfilled throughout centuries of quiet progress in arts and crafts. It was the shattering of all those things for which they praised God in their churches-the good gifts of home-life, the security of the family, the impregnable stronghold, as it seemed, of prosperity built by labour and thrift now utterly destroyed.

I motored over to Nieuport-les-Bains, the seaside resort of the town of Nieuport itself, which is a little way from the coast. It was one of those Belgian watering-places much beloved by the Germans before their guns knocked it to bits -a row of red-brick villas with a few pretentious hotels utterly uncharacteristic of the Flemish style of architecture, lining a promenade and built upon the edge of dreary and monotonous sand-dunes. On this day the place and its neighbourhood were utterly and terribly desolate. The only human beings I passed on my car were two seamen of the British Navy, who were fixing up a wireless apparatus on the edge of the sand. They stared at our ambulances curiously, and one of them gave me a prolonged and strenuous wink, as though to say, "A fine old game, mate, this bloody war! " Beyond, the sea was very calm, like liquid lead, and a slight haze hung over it, putting a gauzy veil about a line of British and French monitors which lay close to the coast. Not a soul could be seen along the promenade of Nieuport-les-Bains, but the body of a man - a French marine - whose soul had gone in flight upon the great adventure of eternity, lay at the end of it with his sightless eyes staring up to the grey sky. Presently I was surprised to see an elderly civilian and a small boy come out of one of the houses. The man told me he was the proprietor of the Grand Hotel, " but," he added, with a gloomy smile, " I have no guests at this moment In a little while, perhaps my hotel will have gone also." He pointed to a deep hole ploughed up an hour ago by a German " Jack Johnson." It was deep enough to bury a taxicab.

For some time, as I paced up and down the promenade, there was no answer to the mighty voices of the naval guns firing from some British warships lying along the coast.

Nor did any answer come for some time to a French battery snugly placed in a hollow of the dunes, screened by a few trees. I listened to the overwhelming concussion of each shot from the ships, wondering at the mighty flight of the shell, which travelled through the air with the noise of an express train rushing through a tunnel. It was curious that no answer came ! Surely the German batteries beyond the river would reply to that deadly cannonade.

I had not long to wait for the inevitable response. It came with a shriek, and a puff of bluish smoke, as the German shrapnel burst a hundred yards from where I stood. It was followed by several shells which dropped into the dunes, not far from the French battery of cent-vingt. Another knocked off the gable of a villa.

1 had been pacing up and down under the shelter of a red-brick wall leading into the courtyard of a temporary hospital, and presently, acting upon orders from Lieutenant de Broqueville, I ran my car up the road with a Belgian medical officer to a place where some wounded men were lying. When I came back again the red-brick wall had fallen into a heap. The Belgian officer described the climate as " quite unhealthy," as I went away with two men dripping blood on the floor of the car. They had been brought across the ferry, further on, where the Belgian trenches were being strewn with shrapnel. Another little crowd of wounded men was there. Many of them had been huddled up all night, wet to the skin, with their wounds undressed, and without any kind of creature comfort. Their condition had reached the ultimate bounds of misery, and with two of these poor fellows I went away to fetch hot coffee for the others, so that at last they might get a little warmth if they had strength enough to drink. . . . That evening, after a long day in the fields of death, and when I came back from the village where men lay waiting for rescue or the last escape, I looked across to Nieuport-les-Bains. There were quivering flames above it and shells were bursting over it with pretty little puffs of smoke which rested in the opalescent sky. I thought of the proprietor of the Grand Hotel, and wondered if he had insured his house against "Jack Johnsons."

Early next morning I paid a visit to the outskirts of Nieuport town, inland. It was impossible to get further than the outskirts at that time, because in the centre houses were falling and flames were licking each other across the roadways. It was even difficult for our ambulances to get so far, because we had to pass over a bridge to which the enemy's guns were paying great attention. Several of their thunderbolts fell with a hiss into the water of the canal where sonic Belgian soldiers were building a bridge of boats. It was just an odd chance that our ambulance could get across without being touched, but we took the chance and dodged between two shell-bursts. On the other side, on the outlying streets, there was a litter of bricks and broken glass, and a number of stricken men lay huddled in the parlour of a small house to which they had been carried. One man was holding his head to keep his brains from spilling, and the others lay tangled amidst upturned chairs and cottage furniture. There was the photograph of a family group on the mantel-piece, between cheap vases which had been the pride, perhaps, of this cottage home. On one of the walls was a picture of Christ with a bleeding heart.

I remember that at Nieuport there was a young Belgian doctor who had established himself at a dangerous post within range of the enemy's guns, and close to a stream of wounded who came pouring into the little house which he had made into his field hospital. He had collected also about twenty old men and women who had been unable to get away when the first shells fell. Without any kind of help he gave first aid to men horribly torn by the pieces of flying shell, and for three days and nights worked very calmly and fearlessly, careless of the death which menaced his own life.

Here he was found by the British column of field ambulances, who took away the old people and relieved him of the last batch of blessés. They told the story of that doctor over the supper-table that night, and hoped he would be remembered by his own people. . . .

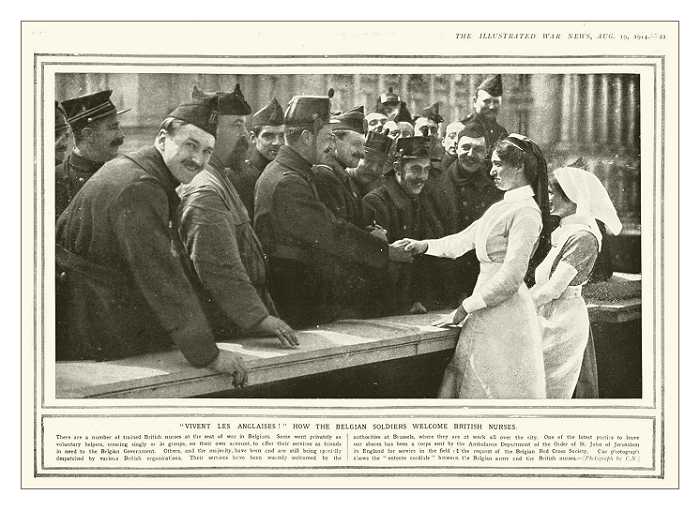

There were picnic parties on the Belgian roadsides. Looking back now upon those luncheon hours, with khaki ambulances as shelters from the shrewd wind that came across the marshes, I marvel at the contrast between their gaiety and the brooding horror in the surrounding scene. Bottles of wine were produced and no man thought of blood when he drank its redness, though the smell of blood reeked from the stretchers in the cars. There were hunks of good Flemish cheese with, fresh bread and butter, and it was extraordinary what appetites we had, though guns were booming a couple of kilometres away and the enemy was smashing the last strongholds of the Belgians. The women in their field kits so feminine though it included breeches, gave a grace to those wayside halts, and gave to dirty men the chance of little courtesies which brought back civilization to their thoughts, even though life had gone back to primitive things with just life and death, hunger and thirst, love and courage, as the laws of existence. The man who had a corkscrew could command respect. A lady with gold-spun hair could gnaw a chicken bone without any loss of beauty. The chauffeurs munched solidly, making cockney jokes out of full mouths and abolishing all distinctions of caste by their comradeship in great adventures when their courage, their cool nerve, their fine endurance at the wheel, and their skill in taking heavy ambulances down muddy roads with skidding wheels, saved many men's lives and won a heartfelt praise. Little groups of Belgian soldiers came up wistfully and lingered round us as though liking the sight of us, and the sound of our English speech, and the gallantry of those girls who went into the firing-lines to rescue their wounded.

"They are wonderful, your English ladies," said a bearded man. He hesitated a moment and then asked timidly: Do you think I might shake hands with one of them ? "

I arranged the little matter, and he trudged off with a flush on his cheeks as though he had been in the presence of a queen, and graciously received.

The Belgian officers were eager to be presented to these ladies and paid them handsome compliments. I think the presence of these young women with their hypodermic syringes and first-aid bandages, and their skill in driving heavy motor-cars, and their spiritual disregard of danger, gave a sense of comfort and tenderness to those men who had been long absent from their women-folk and long-suffering in the bleak and ugly cruelty of war. There was no false sentiment, no disguised gallantry, in the homage of the Belgians to those ladies. It was the simple, chivalrous respect of soldiers to dauntless women who had come to help them when they were struck down and needed pity.

Women, with whom for a little while I could call myself comrade, I think of you now and marvel at you. The call of the wild had brought some of you out to those fields of death. The need of more excitement than modern life gives in time of peace, even the chance to forget, had been the motives with which two or three of you, I think, came upon these scenes of history, taking all risks recklessly, playing a man's part with a feminine pluck, glad of this liberty, far from the conventions of the civilized code, yet giving no hint of scandal to sharp-eared gossip. But most of you had no other thought than that of pity and helpfulness, and with a little flame of faith in your hearts you bore the weight of bleeding men, and eased their pain when it was too intolerable. No soldiers in the armies of the Allies have better right to wear the decorations which a king of sorrow gave you for your gallantry in action.

The Germans were still trying to smash their way through the lines held by the Belgians, with French support. They were making tremendous attacks at different places, searching for the breaking-point by which they could force their way to Furnes and on to Dunkirk. It was difficult to know whether they were succeeding or failing. It is difficult to know anything on a modern battlefield where men holding one village are ignorant of what is happening in the next, and where all the sections of an army seem involved in a bewildering chaos, out of touch with each other, waiting for orders which do not seem to come, moving forward £9r no apparent, reason, retiring for other reasons hard to or resting, without firing a shot, in places searched by the enemy's fire.