An American Journalist with the Allies

THE RED BADGE OF MERCY

CORPORAL EMILE DUPONT, having finished a most unappetizing and unsatisfying breakfast, consisting of a cup of lukewarm chicory and a half-loaf of soggy bread, emerged on all fours from the hole in the ground which for many months had been his home and, standing upright in the trench, lighted a cigarette. At that instant some-thing came screaming out of nowhere to burst, in a cloud of acrid smoke and a shower of steel splinters, directly over the trench in which Emile was standing. Immediately the sky seemed to fall upon Emile and crush him. When he returned to consciousness a few seconds later he found himself crumpled up in an angle of the trench like an empty kit-bag that has been hurled into a corner of a room. He felt curiously weak and nauseated; he ached in every bone in his body; his head throbbed and pounded until he thought that the top of his skull was coming off. Still, he was alive, and that was something. He fumbled for the cigarette that he had been lighting, but there was a curious sensation of numbness in his right hand. He did not seem to be able to move it.

Very slowly, very painfully he turned his head so that his eyes travelled out along his blue-sleeved arm until they reached the point where his hand ought to be. But the hand wasn't there. It had quite disappeared. His wrist lay in a pool of something crimson and warm and sticky which widened rapidly as he looked at it. His hand was gone, there was no doubting that. Still, it didn't interest him greatly ; in fact, it might have been some other man's hand for all he cared. His head throbbed like the devil and he was very, very tired. Rather dimly he heard voices and, as through a haze, saw figures bending over him. He felt some one tugging at the little first-aid packet which every soldier carries in the breast of his tunic, he felt something being tied very tightly around his arm above the elbow, and finally he had a vague recollection of being dragged into a dug-out, where he lay for hours while the shell-storm raged and howled outside.

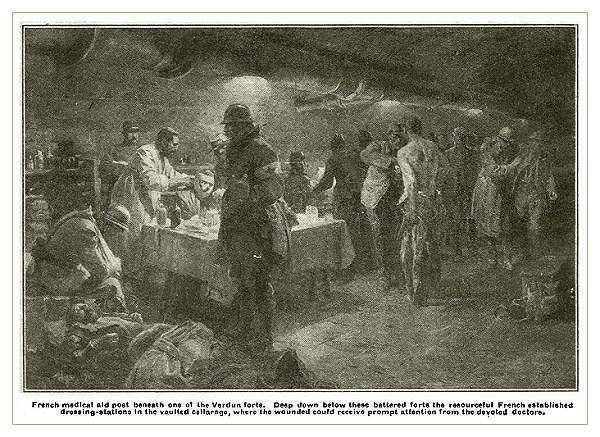

Toward nightfall when the bombardment had died down, two soldiers, wearing on their arms white brassards with red crosses, lifted him on to a stretcher and carried him between interminable walls of brown earth to another and a larger dug-out which he recognized as a poste de secours. After an hour of waiting, because there were other wounded men who had to be attended to first, the stretcher on which Emile lay was lifted on to a table, over which hung a lantern. A bearded man, wearing the cap of a medical officer, and with a white apron up to his neck, briskly unwound the bandages which hid the place where Emile's right hand should have been. "It'll have to be taken off a bit further up, mon brave," said the surgeon, in much the same tone that a tailor would use in discussing the shortening of a coat. "You seem to be in pretty fair shape, though, so we'll just give you a new dressing, and send you along to the field ambulance, where they have more facilities for amputating than we have here." Despite the pain, which had now become agonizing, Emile watched with a sort of detached admiration the neatness and despatch with which the surgeon wound the white bandages around the wound. It reminded him of a British soldier putting on his puttees.

"Just a moment, my friend," said the surgeon, when the dressing was completed, "we'll give you a jab of this before you go, to frighten away the tetanus," and in the muscles of his shoulder Emile felt the prick of a hypodermic needle. An orderly tied to a button of his coat a pink tag on which something-he could not see what-had been scrawled by the surgeon, and two brancardiers lifted the stretcher and carried him out into the darkness. From the swaying of the stretcher and the muffled imprecations of the bearers, he gathered that he was being taken across the ploughed field which separated the trenches from the highway where the ambulances were waiting. "This cleans 'em up for to-night," said one of the bearers, as he slipped the handles of the stretcher into the grooved supports of the ambulance and pushed it smoothly home.

“Thank God for -“ said the ambulance driver, as he viciously cranked his car. "I thought I was going to be kept here all night. It's time we cleared out anyway. The Boches spotted me with a rocket they sent up a while back, and they've been dropping shells a little too close to be pleasant.

“Well, s'long. When I get this bunch delivered I'm going to turn in and get a night's sleep."

The road, being paved with cobblestones, was not as smooth as it should have been for wounded men. Emile, who had been awakened to full consciousness by the night air and by a drink of brandy one of the orderlies at the poste de secours had given him, felt something warm and sticky falling . . . drip . . . drip . . drip . . . upon his face. In the dim light he was at first unable to discover where it came from. Then he saw. It was dripping through the brown canvas of the stretcher that hung above him. He tried to call to the ambulance driver, but his voice was lost in the noise of the machine. The field-hospital was only three miles behind the trench in which he had been wounded, but by the time he arrived there, what with the jolting and the pain and the terrible thirst which comes from loss of blood and that ghastly drip . . . drip . . . drip in his face, Emile was in a state of both mental and physical collapse. They took him into a large tent, dimly lighted by lanterns which showed him many other stretchers with silent or groaning forms, all ticketed like himself, lying upon them. After considerable delay a young officer came around with a notebook and looked at the tag they had tied on him at the dressing- station. On it was scrawled the word "urgent." That admonition didn't prevent Emile's having to wait two hours before he was taken into a tent so brilliantly illuminated by an arc-lamp that the glare hurt his eyes. When they laid him on a narrow white table so that the light fell full upon him he felt as though he were on the stage of a theatre and the spot-light had been turned upon him. An orderly with a sharp knife deftly slashed away the sleeve of Emile's coat, leaving the arm bare to the shoulder, while another orderly clapped over his mouth and nose a sort of funnel.

When he returned to consciousness be found himself again in an ambulance rocking and swaying over those agonizing pavé roads. The throbbing of his head and the pain in his arm and the pitching of the vehicle made him nauseated. There were three other wounded men in the ambulance and they had been nauseated too. It was not a pleasant journey. After what seemed to Emile and his companions in misery an interminable time, the ambulance train finally pulled under the sooty glass roof of the Paris station, Emile was hovering between life and death. He had a hazy, indistinct recollection of being taken from the ill-smelling freight-car to an ambulance-the third in which he had been in less than forty-eight hours ; of skimming pleasantly, silently over smooth pavements; of the ambulance entering the porte-cochere of a great white building that looked like a hotel or school. Here he was not kept waiting. Nurses with skilful fingers drew off his clothes-the filthy, blood-soaked, mud-stained, vermin- infested, foul-smelling garments that he had not had off for many weeks. He was lowered, ever so gently, into a tub filled with warm water. Bon Dieu, but it felt good ! It was the first warm bath that he had had for more than a year. It was worth being wounded for. Then a pair of flannel pyjamas, a fresh, soft bed, such as he had not known since the war began, and pink-cheeked nurses in crisp, white linen slipping about noiselessly.

While Emile lay back on his pillows and puffed a cigarette a doctor came in and dressed his wound. "Don't worry about yourself, my man," he said cheerily, "you'll get along finely. In a week or so we'll be sending you back to your family." Whereupon Corporal Emile Dupont turned on his pillow with a great sigh of content. He wondered dimly, as he fell asleep, if it would be hard to find work which a one-armed man could do.

From the imaginary but wholly typical case just given, in which we have traced the course of a wounded man from the spot where he fell to the final hospital, it will be seen that the system of the Service de Santé Militaire, as the medical service of the French army is known, though cumbersome and complicated in certain respects, nevertheless works-and works well. In understanding the French system it is necessary to bear in mind that the wounded man has to be shifted through two army zones, front and rear, both of which are under the direct control of the commander-in-chief, to the interior zone of the country, with its countless hospitals, which is under the direction of the Ministry of War.

As soon as a soldier falls he drags himself, if he is able, to some sheltered spot, or his comrades carry him there, and with the "first-aid" packet, carried in the breast pocket of the tunic, an endeavour is made to give the wound temporary treatment. In the British service this "first-aid " kit consists of a small tin box, not much larger than a cigarette case, containing a bottle of iodine crystals and a bottle of alcohol wrapped up in a roll of aseptic bandage gauze. Meanwhile word has been passed along the line that the services of the surgeon are needed, for each regiment has one and sometimes two medical officers on duty in the trenches. It may so happen that the trench section has its own poste de secours, or first-aid dressing-station, in which case the man is at once taken there.

The medical officer dresses the man's wound, perhaps gives him a hypodermic injection to lessen the pain, and otherwise makes him as comfortable as possible under the circumstances. His wounds temporarily dressed, if there is a dug-out at hand, he is taken into it. If not, he is laid in such shelter as the trench affords, and there he usually has to lie until night comes and he can be removed in comparative safety; for, particularly in the flat country of Artois and Flanders, it is out of the question to remove the wounded except under the screen of darkness, and even then it is frequently an extremely hazardous proceeding, for the German gunners apparently do their best to drop their shells on the ambulances and stretcher parties. As soon as night falls a dressing-station is established at a point as close as possible behind the trenches, the number of surgeons, dressers, and stretcher-bearers sent out depending upon the number of casualties as reported by telephone from the trenches to headquarters. The wounded man is transported on a stretcher or a wheeled litter to the dressing-station, where his wounds are examined by the light of electric torches and, if necessary, redressed. If he has any fractured bones they are made fast in splints or pieces of zinc or iron wire-anything that will enable him to stand transportation. Though the dressing- station is, wherever possible, established in a farmhouse, in a grove, behind a wall, or such other protection as the region may afford, it is, nevertheless, often in extreme danger.

I recall one case, in Flanders, where the flashing of the torches attracted the attention of the German gunners, who dropped a shell squarely into a dressing-station, killing all the surgeons and stretcher-bearers, and putting half a dozen of the wounded out of their misery. As soon as the wounded man has passed through the dressing-station, he is carried, usually over very rough ground, to the point on the road where the motor- ambulances are waiting and is whirled off to the division ambulance, which corresponds to the field-hospital of the British and American armies. These division ambulances (it should be borne in mind that the term ambulance in French means "military hospital ") do as complete work as can be expected so near the front. They are usually set up only four or five miles behind the firing-line, and have a regular medical and nursing staff, instruments, and, in some cases, X-ray apparatus for operations. As a rule, only light emergency operations are performed in these ambulances of the front- light skull trepanning, removal of splintered bones, disinfection, and immobilizing of the wounded parts.

At the beginning of the war it was an accepted principle of the French army surgeons not to operate at the front, but simply to dress the wounds so as to permit of speedy transportation to the rear, for the division ambulances, being without heat or light or sterilizing plants of their own, had no facilities for many urgent operations or for night work. Hence, though there was no lack of surgical aid at the front, major operations were not possible, and thousands of men died who, could they have been operated on immediately, might have been saved. This grave fault in the French medical service has now been remedied, however, by the automobile surgical formations created by Doctor Marcille. Their purpose is to bring within a few miles of the spot where fighting is in progress and where men are being wounded the equivalent of a great city emergency hospital, with its own sterilization plant, and an operating-room heated and lighted powerfully night and day.

This equipment is extremely mobile, ready to begin work even in the open country within an hour of its arrival, and capable of moving on with the same rapidity to any point where its services may be required. The arrangement of these operating-rooms on wheels is as compact and ingenious as a Pull-man sleeping-car. The sterilization plant, which works by superheated steam, is on an automobile chassis, the surgeons taking their instruments, compresses, aprons, and blouses immediately from one of the six iron sheets of the autoclave as they operate. Six operations can be carried on without stopping-and during the sixth the iron sheets are resterilized to begin again. The same boiler heats a smaller autoclave for sterilizing rubber gloves and water, and also, by means of a powerful radiator, heats the operating-room. This is an impermeable tent, with a large glass skylight for day and a 200-candle power electric light for night, the motor generating the electricity. Another car contains the radiograph plant, while the regular ambulances provide pharmacy and other supplies and see to the further transportation of the wounded who have been operated on. Of seventy operations, which would have all been impossible without these surgical automobile units, fifty-five were successful.

In cases of abdominal wounds, which have usually been fatal in previous wars, fifty per cent. of the operations thus performed saved the lives of the wounded.

Leaving the zone of actual operations, the wounded man now enters the army rear zone, where, at the heads of the lines of communication, hospital trains or hospital canal-boats are waiting for him. The beginning of the war found France wholly unprepared as regards modernly equipped hospital trains, of which she possessed only five, while Russia had thirty-two, Austria thirty-three, and Germany forty. Thanks to the energy of the great French railway companies, the number has been somewhat increased, but France still has mainly to rely on improvised sanitary trains for the transport of her wounded. There are in operation about one hundred and fifty of these improvised trains, made up, when possible, of the long luggage vans of what were before the war the international express trains. As these cars are well hung, are heated, have soft Westinghouse brakes, and have corridors which permit of the doctors going from car to car while the train is in motion, they answer the purpose to which they have been put tolerably well. But when heavy fighting is in progress, rolling stock of every description has to be utilized for the transport of the wounded.

Those who can sit up without too much discomfort are put in ordinary passenger cars. But in addition to these the Service de Santé has been compelled to use thousands of goods and cattle trucks glassed up at the sides and with a stove in the middle. The stretchers containing the most serious cases are, by means of loops into which the handles of the stretchers fit, laid in two rows, one above the other, at the ends of each truck, while those who are able to sit up are gathered in the centre. Each truck is in charge of an orderly who keeps water and soups constantly heated on the stove. Any one who has travelled for any distance in a goods or cattle truck will readily appreciate, however, how great must be the sufferings of the wounded men thus transported. Taking advantage of the network of canals and rivers which covers France, the medical authorities of the army have also utilized canal-boats for the transport of the blessés - a method of transportation which, though slow, is very easy. Every few hours these hospital trains or boats come to "infirmary stations," established by the Red Cross, where the wounded are given food and drink, and their dressing is looked after, while at the very end of the army zones there are "regular stations," where the " evacuation hospitals " are placed. Here is where the sorting system comes in. There are wounded whose condition has become so aggravated that it is out of the question for them to stand a longer journey, and these remain. There are lightly wounded, who, with proper attention, will be as well as ever in a few days, and these are sent to a dépot des éclopés, or, as the soldiers term it, a "limper's halt." Then there are the others who, if they are to recover, will require long and careful treatment and difficult operations. These go on to the final hospitals of the interior zone : military hospitals, auxiliary hospitals, civil hospitals militarized, and "benevolent hospitals," such as the great American Ambulance at Neuilly. (*see American Ambulance Hospital in Paris)

No account of the work of caring for the wounded would be complete without at least passing mention of the American Ambulance, which, founded by Americans, with an American staff and an American equipment, and maintained by American generosity, has come to be recognized as the highest type of military hospital in existence. At the beginning of the war, Americans in Paris, inspired by the record of the American Ambulance in 1870, and foreseeing the needs of the enormous number of wounded which would soon come pouring in, conceived the idea of establishing a military hospital for the treatment of the wounded, irrespective of nationality. The French Government placed at their disposal a large and nearly completed school building in the suburb of Neuilly, just outside the walls of Paris. Before the war had been in progress a month this building had been transformed into perhaps the most up-to-the-minute military hospital in Europe, equipped with X-ray apparatus, ultra violet-ray sterilizing plants, a giant magnet for removing fragments of shell from wounds, a pathological laboratory, and the finest department of dental surgery in the world. The feats of surgical legerdemain performed in this latter department are, indeed, almost beyond belief. The American dental surgeons assert - and they have repeatedly made their assertion good - that, even though a man's entire face has been blown away, they can construct a new and presentable countenance, provided the hinges of the jaws remain.

Beginning with 170 beds, by November 1915 the hospital had 600 beds and in addition has organized an "advanced hospital," with 250 beds, known as Hospital B, at Juilly, which is maintained through the generosity of Mrs. Harry Payne Whitney ; a field hospital, of the same pattern as that used by the United States Army, with 108 beds; and two convalescent hospitals at St. Cloud ; the staff of this remarkable organization comprising doctors, surgeons, graduate and auxiliary nurses, orderlies, stretcher- bearers, ambulance drivers, cooks, and other employees to the number of seven hundred. Perhaps the most picturesque feature of the American hospital is its remarkable motor-ambulance service, which consists of 130 cars and 160 drivers. The ambulances, which are for the most part Ford cars with specially designed bodies, have proved so extremely practical and efficient that the type has been widely copied by the Allied armies. They serve where they are most needed, being sent out in units (each unit consisting of a staff car, a supply car, and five ambulances) upon the requisition of the military authorities. The young men who drive the ambulances and who, with a very few exceptions, not only serve without pay but even pay their own passage from America and provide their own uniforms, represent all that is best in American life : among them are men from the great universities both East and West, men from the hunt clubs of Long Island and Virginia, lawyers, novelists, polo-players, big game hunters, cow-punchers, while the inspector of the ambulance service is a former assistant treasurer of the United States. American Ambulance units are stationed at many points on the western battle-line - I have seen them at work in Flanders, in the Argonne, and in Alsace - the risks taken by the drivers in their work of bringing in the wounded and their coolness under fire having won for them among the soldiers the admiring title of "bullet biters."

The British system of handling the wounded is upon the same general lines as that of the French, the chief difference being in the method of sorting, which is the basis of all medical corps work in this war.

Sorting, as practised by the British, starts at the very first step in the progress of a wounded man, which is the dressing-station in or immediately behind the trenches, where only those cases absolutely demanding it are dressed and where only the most imperative operations are performed. The second step is the field hospital, where all but a few of the slight wounds are dressed, and where operations that must be done before the men can be passed farther back are performed. The third step is the clearing hospital, at the head of railway communication. Here the man receives the minimum of medical attention before being passed on to the hospital train which conveys him to one of the great base hospitals on the coast, where every one, whether seriously or slightly wounded, can at last receive treatment. To the wounded Tommy, the base hospital is the half-way house to home, where he is cared for until he is able to stand the journey across the Channel to England.

The real barometer of battle is the clearing hospital, for one can always tell by the number of cases coming in whether there is heavy fighting in progress. As both field and clearing hospitals move with the armies, they must not only always get rid of their wounded at the earliest possible moment, but they must always be prepared for quick movements backward or forward. Either a retreat or an offensive movement necessitates quick action on the part of the Army Medical Corps, for it is a big job to dismantle a great hospital, pack it up, and start the motor-transport within an hour after the order to move is received. It would be a big job without the wounded.

In the French lines the hopital d'evacuation is frequently established in a goods station or warehouse in the midst of the railway yards, so as to facilitate the loading of the hospital trains. This arrangement has its drawbacks, however, for the hospital is liable to be bombarded by aeroplanes or artillery without warning, as it is a principle recognized - and practised - by all the belligerent nations that it is perfectly legitimate to shell a station or railway base in order to interfere with the troops, supplies, and ammunition going forward to the armies in the field. That a hospital is quartered in the station is unfortunate but must be disregarded. At Dunkirk, for example, which is a fortified town and a base of the very first importance, there was nothing unethical, from a military view-point, in the Germans shelling the railway yards, even though a number of wounded in the hospital there lost their lives. The British avoid this danger by establishing their clearing hospitals in the outskirts of the terminus towns, and as far from the station as possible, which, however, necessitates one more transfer for the wounded man.

In this war the progress made in the science of healing has kept pace with, if indeed it has not outdistanced, the progress made in the science of destruction. There is, for example, the solution of hypochlorite of soda, introduced by Doctor Dakin and Doctor Alexis Carrel, which, though not a new invention, is being used with marvellous results for the irrigation of wounds and the prevention of suppuration. There is the spinal anesthesia, used mainly in the difficult abdominal cases, a minute quantity of which, injected into the spine of the patient, causes all sensation to disappear up to the arms, so that, provided he is prevented by a screen from seeing what is going on, an operation below that level may be performed while the patient, wholly unconscious of what is happening, is reading a paper or smoking a cigarette. Owing to failure to disinfect the wounds at the front, many of the cases reaching the hospitals in the early days of the war were found to be badly septic, the infection being due, curiously enough, to the nature of the soil of the country, the region of the Aisne, for example, apparently being saturated with the tetanus germ. So the doctors invented an anti- tetanus serum, with which a soldier can inoculate himself, and as a result, the cases of tetanus have been reduced by half. It was found that many wounded men failed to recover because of the minute pieces of shell remaining in their bodies, so there was introduced the giant magnet which, when connected with the probe in the surgeon's hand, unerringly attracts and draws out any fragments of metal that may remain in the wound. Still another ingenious invention produced by the war is the bell, or buzzer, which rings when the surgeon's probe approaches a foreign substance.

Though before the war began European army surgeons were thoroughly conversant with the best methods of treating shell, sabre, and bullet wounds and the innumerable diseases peculiar to armies, the war has produced one weapon of which they had never so much as heard before, and the effects of which they were at first wholly unable to combat. I refer to the asphyxiating gas. If you fail to understand what "gassing" means, just listen to this description by a British army surgeon:

In a typical 'gassed' case the idea of impending suffocation predominates. Every muscle of respiration is called upon to do its utmost to avert the threatened doom. The imperfect aeration of the blood arising from obstructed respiration causes oftentimes intense blueness and clamminess of the face, while froth and expectoration blow from the mouth impelled by a choking cough. The poor fighting man tosses and turns himself into every position in search of relief. But his efforts are unavailing; he feels that his power of breathing is failing ; that asphyxiation is gradually becoming complete. The slow strangling of his respiration, of which he is fully conscious, at last enfeebles his strength. No longer is it possible for him to expel the profuse expectoration ; the air tubes of his lungs become distended with it, and with a few gasps he dies.

If the 'gassed ' man survives the first stage of his agony, some sleep may follow the gradual decline of the urgent symptoms, and after such sleep he feels refreshed and better. But further trouble is in store for him, for the intense irritation to which the respiratory passages have been exposed by the inhalation of the suffocating gas is quickly followed by the supervention of acute bronchitis. In such attacks death may come, owing to the severity of the inflammation. In mild cases of ' gassing,' on the other hand, the resulting bronchitis develops in a modified form with the result that recovery now generally follows. Time, however, can only show to what extent permanent damage to the lungs is inflicted. Possibly chronic bronchitis may be the lot of such 'gassed ' men in after life or some pulmonary trouble equally disturbing. It is difficult to believe that they can wholly escape some evil effects."

As soon as it was found that the immediate cause of death in the fatal gas cases was acute congestion of the lungs, the surgeons were able to treat it upon special and definite lines. Means were devised for ensuring the expulsion of the excessive secretion from the lungs, thus affording much relief and making it possible to avert asphyxiation. In some apparently hopeless cases the lives of the men were saved by artificial respiration. The inhalation of oxygen was also tried with favourable results, and in cases where the restlessness of the patient was more mental than physical, opium was successfully used. So that even the poison-gas, perhaps the most dreadful death-dealing device which the war has produced, neither dismayed nor defeated the men whose task it is to save life instead of to take it.

To the surgeons and nurses at the front the people of France and England owe a debt of gratitude which they can never wholly repay. The soldiers in the trenches are waging no more desperate or heroic battle than these quiet, efficient, energetic men and women who wear the red badge of mercy. Their courage is shown by the enormous losses they have suffered under fire, the proportion of military doctors and hospital attendants killed, wounded, or taken prisoner, equalling the proportion of infantry losses. They have no sleep save such as they can snatch between the tides of wounded or when they drop on the floor from sheer exhaustion. They are working under as trying conditions as doctors and nurses were ever called upon to face. They treat daily hundreds of cases, any one of which would cause a town physician to call a consultation. They are in constant peril from marauding Taubes, for the German air- men seem to take delight in choosing buildings flying the Red Cross flag as targets for their bombs. In their ears, both day and night, sounds the din of near-by battle. Their organization is a marvel of efficiency. That of the Germans may be as good but it can be no better.

In order that I may bring home to you in England and America the realities of this thing called war, I want to tell you what I saw one day in a little town called Bailleul. Bailleul is only two or three miles on the French side of the Franco-Belgian frontier, and it is so close to the firing-line that its windows continually rattle. The noise along that portion of the battle-front never ceases. It sounds for all the world like the clatter of a gigantic harvester. And that is precisely what it is-the harvester of death.

As we entered Bailleul they were bringing in the harvest. They were bringing it in motorcars, many, many, many of them, stretching in endless procession down the yellow roads which lead to Lille and Neuve Chapelle and Poperinghe and Ypres. Over the grey bodies of the motor-cars were grey canvas hoods, and painted on the hoods were staring scarlet crosses. The curtain at the back of each car was rolled up, and protruding from the dim interior were four pairs of feet. Sometimes those feet were wrapped in bandages, and on the fresh white linen were bright-red splotches, but more often they were encased in worn and muddied boots. I shall never forget those poor, broken, mud-encrusted boots, for they spoke so eloquently of utter weariness and pain. There was something about them that was the very essence of pathos. The owners of those boots were lying on stretchers which were made to slide into the ambulances as drawers slide into a bureau, and most of them were suffering agony such as only a woman in childbirth knows.

This was the reaping of the grim harvester which was at its work of mowing down human beings not five miles away. Sometimes, as the ambulances went rocking by, I would catch a fleeting glimpse of some poor fellow whose wounds would not permit of his lying down. I remember one of these in particular - a clean-cut, fair-haired youngster who looked as if he were still in his teens. He was sitting on the floor of the ambulance leaning for support against the rail. He held his arms straight out in front of him. Both his hands had been blown away at the wrists. The head of another was so swathed in bandages that my first impression was that he was wearing a huge red-and- white turban. The jolting of the car had caused the bandages to slip. If that man lives little children will run from him in terror, and women will turn aside when they meet him in the street. And still that caravan of agony kept rolling by, rolling by. The floors of the cars were sieves leaking blood. The dusty road over which they had passed no longer needed sprinkling.

Tearing over the rough cobbles of Bailleul, the ambulances came to a halt before some one of the many doorways over which droop the Red Cross flags, for every suitable building in the little town has been converted into a hospital. The one of which I am going to tell you had been a school until the war began. It is officially known as Clearing Hospital Number Eight, but I shall always think of it as hell's antechamber. In the afternoon that I was there eight hundred wounded were brought into the building between the hours of two and four, and this, mind you, was but one of many hospitals in the same little town. As I entered the door I had to stand aside to let a stretcher carried by two orderlies pass out. Through the rough brown blanket which covered the stretcher showed the vague outlines of a human form, but the face was covered, and it was very still. A week or two weeks or a month later, when the casualty lists were published, there appeared the name of the still form under the brown blanket, and there was anguish in some English home. In the hall of the hospital a man was sitting upright on a bench, and two surgeons were working pull through, but he'll never recover his reason. "Can't you see him in the years to come, this splendid specimen of manhood, his mind a blank, wandering, helpless as a little child, about some English village ?”

I doubt if any four walls in all the world contain more human suffering than those of Hospital Number Eight at Bailleul, yet of all those shattered, broken, mangled men I heard only one utter a complaint or groan. He was a fair-haired giant, as are so many of these English fighting men. A bullet had splintered his spine, and with his hours numbered, he was suffering the most awful torment that a human being can endure. The sweat stood in beads upon his forehead. The muscles of his neck and arms were so corded and knotted that it seemed as though they were about to burst their way through the sun-tanned skin. His naked breast rose and fell in great sobs of agony. "Oh God! Oh God!" he moaned, “be merciful and take me - it hurts, it hurts, - it hurts me so- my wife - the kiddies - for the love of Christ, doctor, give me an injection and stop the pain - say good-bye to them for me - tell them, I can't stand it any longer-I'm not afraid to die, doctor, but I just can't stand this pain God, dear God, won't you please let me die? " When I went out of that room the beads of sweat were standing on my forehead.

They took me downstairs to show me what they call the "evacuation ward." It is a big, barn-like room, perhaps a hundred feet long by fifty wide, and the floor was so thickly covered with blanketed forms on stretchers that there was no room to walk about among them. These were the men whose wounds had been treated, and who, it was believed, were able to survive the journey by hospital train to one of the base hospitals on the coast. It is a very grave case indeed that is permitted to remain for even a single night in the hospitals in Bailleul, for Baileul is but a clearing-house for the mangled, and its hospitals must always be ready to receive that unceasing scarlet stream which, day and night, night and day, comes pouring in, pouring in, pouring in.

Those of the wounded in the evacuation ward who were conscious were for the most part cheerful - as cheerful, that is, as men can be whose bodies have been ripped and drilled and torn by shot and shell, who have been strangled by poisonous gases, who are aflame with fever, who are faint with loss of blood, and who have before them a railway journey of many hours. This railway journey to the coast is as comfortable as human ingenuity can make it, the trains with their white enamelled interiors and swinging berths being literally hospitals on wheels, but to these weakened, wearied men it is a terribly trying experience, even though they know that at the end of it clean beds and cool pillows and soft-footed, low-voiced nurses await them.

The men awaiting transfer still wore the clothes in which they had been carried from the trenches, though in many cases they had been slashed open so that the surgeons might get at the wounds. They were plastered with mud. Many of them had had no opportunity to bathe for weeks and were crawling with vermin. Their underclothes were in such a loathsome condition that when they were removed they fell apart. The canvas stretchers on which they lay so patiently and uncomplainingly were splotched with what looked like wet brown paint, and on this horrid sticky substance were swarms of hungry flies. The air was heavy with the mingled smells of antiseptics, perspiration, and fresh blood. In that room was to be found every form of wound which can be inflicted by the most hellish weapons the brain of man has been able to devise. The wounded were covered with coarse woollen blankets, but some of the men in their torment had kicked their coverings off, and I saw things which I have no words to tell about and which I wish with all my heart that I could forget. There were men whose legs had been amputated up to the thighs; whose arms had been cut off at the shoulder ; there were men who had lost their eyesight and all their days must grope in darkness; and there were other men who had been ripped open from waist to neck so that they looked like the carcasses that hang in front of butcher's shops ; while, most horrible of all, were those who, without a wound on them, raved and cackled with insane mirth at the horror of the things they had seen.

We went out from that place of unforgettable horrors into the sunlight and the clean fresh air again. It was late afternoon, the birds were singing, a gentle breeze was whispering in the tree-tops ; but from over there, on the other side of that green and smiling valley, still came the unceasing clatter of that grim harvester garnering its crop of death. On the ground, in the shade of a spreading chestnut-tree, had been laid a stretcher, and on it was still another of those silent, bandaged forms. "He is badly wounded," said the surgeon, following the direction of my glance, "fairly shot to pieces. But he begged us to leave him in the open air. We are sending him on by train to Boulogne tonight, and then by hospital ship to England."

I walked over and looked down at him. He could not have been more than eighteen-just such a clean-limbed, open-faced lad as any girl would have been proud to call sweetheart, any mother son. He was lying very still. About his face there was a peculiar greyish pallor, and on his half-parted lips had gathered many flies. I beckoned to the doctor. "He's not going to England," I whispered; "he's going to sleep in France." The surgeon, after a quick glance, gave an order, and two bearers came and lifted the stretcher and, bore it to a ramshackle outhouse which they call the mortuary, and gently set it down at the end of a long row of other silent forms.

As I passed out through the gateway in the wall which surrounds Hospital Number Eight, I saw a group of children playing in the street.

"Come on," shrilled one of them, "let's play soldier !"

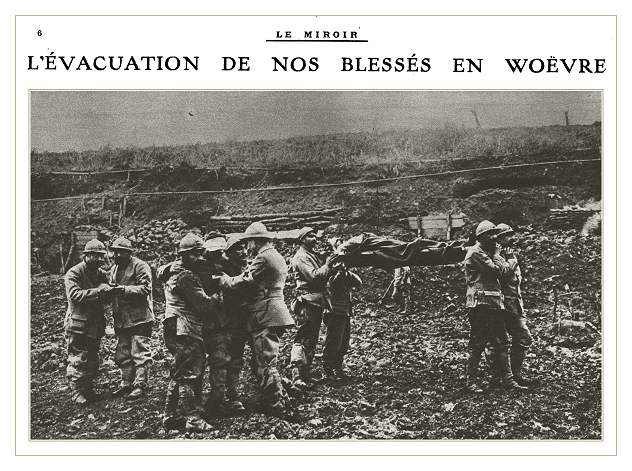

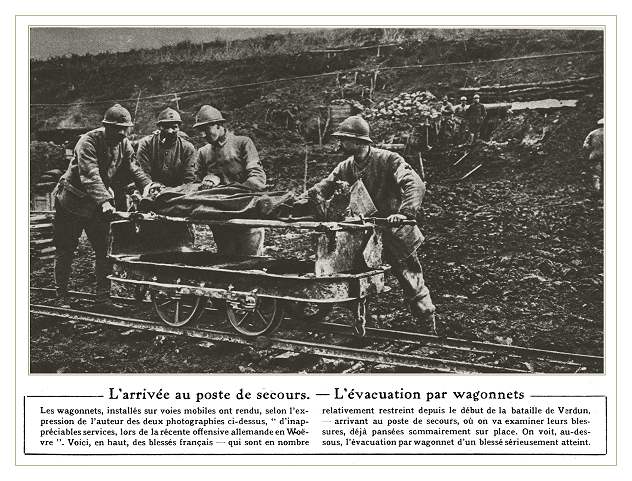

from 'le Miroir' - evacuating French wounded on the Woevre front, east of Verdun