How the Wounded Were Brought Home

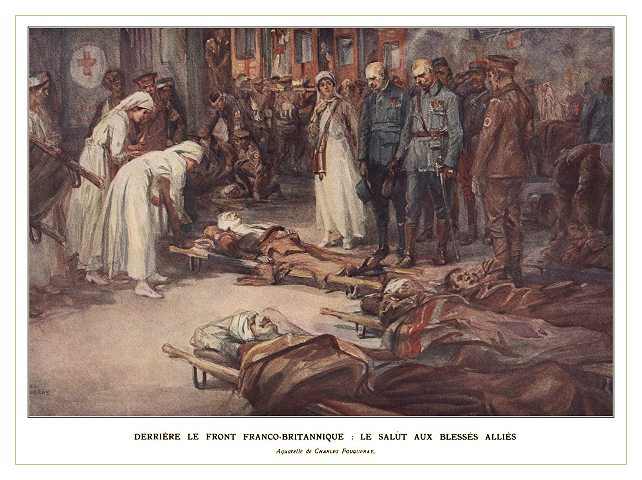

Unloading the Red Cross trains : a romantic French view

HOW THE WOUNDED WERE BROUGHT HOME

By Basil Clarke

EDITORIAL NOTE.-The magnitude attained by the British Army in France was such that the treatment of the casualties became a matter ,of passionately intimate concern to almost every house and cottage in the Empire. It is characteristic of men of our race to be as silent about their sufferings as about their deeds, and the result was that the endurance of the wounded and the devotion of those who tended them seemed likely to remain generally unknown. The Editors of THE GREAT WAR, recognising that the treatment of the wounded was an integral subject of their history, resolved to secure an authentic record of the work from one of their war correspondents, and thus Mr. Basil Clarke, provided with proper credentials and assisted by the cordial co-operation of the military authorities, went to an advanced trench on the Western Front, and, following the regimental stretcher-bearers to the first ease to which they were called, be accompanied a casualty through every stage of the journey from the battlefield to the quayside in England This chapter contains his story, the narrative method adopted giving it a valuable actuality. The Editors wish it to be understood that every incident is true and that the story is an essential part of the history of the war.

“STRETCHER-BEARERS!"

The call came faintly at first from, somewhere down the trench, far away to the right of us ; but other voices took if up and passed it along. Nearer and nearer it came, from voice to voice, some high, some low, till you could see the soldier that shouted it last - a lusty fellow whose ruddy face and green "tin hat" peeped above the rim of the next shell-hole. There, with face towards us and a yellow, muddy hand encircling his mouth for a megaphone, he passed on the words in a deep bass bray; for just as all men in a village community, will stop what they are doing to give a hand in putting out a fire, so will men in a trench help, as a point of honour, to pass on the word for the ambulance men. It is one of the unwritten laws.

The company stretcher-bearers were at tea at the moment in a trench dug-out near me. A corporal pulled aside the sheet of flapping, mud-stained flannel which served the double purpose of door and gas-stop to the dug-out, and shouted in the words "Bearers - right !” Tea was forgotten. One man alone lingered to lift a petrol-can of boiling water from a crackling fire of box-wood; and then he too rambled up the, steps of the dug-out. 'The first man up had seized one of the light stretchers of wooden poles and canvas that stood upright near the dug-out door. "Stretcher - bearers -right!" he shouted, and away to the right they went, six of them, splashing along the trench.

'Trench' is perhaps something ,of an overstatement. It had been a trench when the Germans made it-and a very good one, too. But only four days earlier it had been taken from them after weeks of consistent shelling, and now, what with rain and with shell damage, it was a long series of mud-holes joined together, sometimes by hummocks of earth, sometimes by short lengths of trench, indifferently clear. The part from which we started had been put to rights again or "consolidated," as the official communiqués express it.

The walls had been rebuilt and trued, a parapet had been superimposed upon the enemy's old parados; there were even duck-boards underfoot to walk upon - and duck- boards are the last word in trench comfort. But before the stretcher-bearers ,had, gone very, far-with me plodding slowly behind-the trench reverted once more to its old damaged state as when captured, and to get along it became as hard travelling as any I have known. In places you splashed through a foot of water, otter-hunting fashion; in other places you had to scale hummocks of slimy clay; in others you went through quicksands of viscous, treacle-like fluid that sucked the very boots from one's feet. Many a soldier has come out of one of those mud-pools minus boots, stockings, and puttees.

I myself, who had nightly a battle royal with my top boots to get them off, found them sucked off by that mud as easily as though they had been gripped in the finest bootjack ever invented. The trouble with these holes was to get past them and yet to retain one's foot-wear. But to stand still was to be lost, stuck fast, perhaps even to die, as more than one poor lad has done up on those bleak, muddy slopes of the Somme.

The hundred and fifty yards we went seemed to me one hundred and fifty miles. I arrived a very bad last-as the racing report's might express it - and only just in time to see the six stretcher-bearers putting the finishing touches to the first-aid dressing which they had been applying to one Private John Chatterton HoIlinwood Oldham, of the Cottonopolis Regiment. The corporal was talking as he bound up the wounded limb - quietly "strafing" the injured' one. "Why the divvle you fellows won't keep your field-dressin' in its right place fair beats me. You have a special pocket made in your tunic linin' for it ; you have a nice clean dressin' served out to you in a waterproof bag, and all that's asked of you is that you should keep it in that special pocket, and s'elp me if there's one of you as 'll keep it there ! Is yer 'ed comfy, mate? Take a pull outen my bottle an' a bit of a breather 'fore we starts to yank yer down to the aid post."

Oldham used his interval of rest to tell us how a sniper had caught hint. "Copped me fair, 'e did," he said. "My own fault, too. Ah see'd the blighter earlier this morning, workin' out on 'is belly along the brow of the hill, and had a pop at 'im with my rifle. Missed 'is bloomin' 'ead by about a foot. Saw the spit of my bullet aside his left ear. E' 'opped it quick. But after that ah forgets all about 'im, never thinkin' as ‘e'd crawl out for another go at me. As Ah were crossin' that bit o' open ground about five minutes back 'e pops me one over, fair in the thigh. Ah reckon summut's bust from th' feel on it. Do you think as it's a Blighty' one, corp'ral?”

“Shouldn't be surprised," said the corporal, pretending to be cross. "Beats me why some o' you lads comes 'ere without your mothers. Didn't ye see the notice along that open patch, tellin' you to ''ware snipers'? Ah put it. up myself on that very place an hour after Gummy' Arrison were 'it in th' back on t' same bit o' land. Well, time to be oft. Lie easy, mate, an' we'll 'ave you down in a couple o' shakes. Ready, lads!"'

The bearers, who had been sitting on their haunches on the side of a low hummock of clay, slid down it on their heels. One of them had lit a cigarette during, the rest. He now took it from his. mouth, and without a word stuck it in the mouth of the patient, which opened for it as readily as that of a young chick for food.

“Thanks, matey," he said simply. "Ready? Lift !" Two men held the stretcher-handles. Two men walked at the sides with hands on the stretcher-bars, steadying it and 'taking the weight whenever one of the carriers stumbled - a frequent event. One man walked in front, picking out the best of the track - or, rather, the least difficult of the track. The other walked behind.

How those men ever got that stretcher and its heavy load over the places they did is to this day beyond me. With no further load than a gas-mask and a walking-stick, I had trouble enough myself. At times we came to places where all six men had to give a hand. The poor lad on the stretcher was bemoaning the trouble he was giving. "Can't Ah get out an' walk a bit? " he asked plaintively. "One 0' you gimme a hand an' Ah'll hobble a bit!"

"You howd yer 'ush, my lad! " was all the corporal answered him; and he held it. For his leg was paining badly. I could see him opening and shutting his eyes every now and again with pain. Once he seemed to lose consciousness; then he opened his eyes again, but only for an instant. It was to say: "That sniper feller Fritz 'ad a round fat face an spectacles. 'You'll 'appen to know 'im if ever you sees ‘im messin' about again on the ridge." He was quiet for a minute, then he added : "If you do, any o’ you chaps, you might let 'im know as Ah'nt not 'arf done for yet." Then lie was quiet, his eyes remaining shut.

We came at last to a bit of quaggy road, which one man, by making a dash as over thin ice, might possibly have got through; for six men and a stretcher this was impossible. The corporal called a halt and himself tried the place. "It's no go, lads," he said, scrambling back out of the bog. "We'll have to go outside. But bide a bit, boys; Ah'll make a bit of a look. round." He walked on and shouted warily to a solitary figure with a rifle who was standing thirty yards farther on, upon an island of clay built up in a little sea of water and' mud. "All quiet, mate? " he asked.

"Nowt but a few shells going," came the answer. "A few snipers were out earlier, but they've 'opped it."

"Think we'll be all right to take this fellow outside? He's pretty bad."

"You might," said the other .rather grudgingly, as he looked up at the sky. "Light's beginning to get yeller, and it's agen the snipers. You might be all right,"

The corporal stood in thought for a moment. "Ah'll just 'op out of the trench an' 'ave a look round." And with that the cool fellow climbed 'up the side of the trench remains and, pivoting round on his stomach at the top, lay with his gaze towards the enemy trenches. Pulling his iron helmet low down over his eyes, he looked intently front under the rim. He had been there perhaps a minute, when he suddenly slid headfirst down the trench side which, among its many other imperfections, sloped at this point instead of falling perpendicularly. And at that very moment there was a whistle of bullets just over the trench parapet and shots rang out front the German trenches, less than a hundred yards to the east. The corporal struggled to his feet, muddy but unhurt.

He plodded back to his comrades. "Can't be done yet, boys," he said coolly. "We'll have to wait. Sorry, sonny," 'he added, turning to the man on' the stretcher. "Fritz has not drawn off yet. We'll have .to keep you 'ere till it's a bit darker." He eased the patient's position on the stretcher, saying: "Can'st stick it a bit ? Art 'a all reet ?"

"The lad shivered. "Ay, that cold." And with that the corporal took oft his own greatcoat and spread it over the boy on, the stretcher.

There, in the .cold light of the ebbing day, we waited. The sun sank grudgingly and yellowly behind us, throwing a cold, brassy sheen on to the yellow clay that, encompassed us all about. The colder wind of evening came. You could hear the. faint swish of it over the: trench-tops, and fitful gusts came along the trench - strong enough to make little frills and ruffles on the surface of the water and mud. The patient and his stretcher had been laid on a strip of ledge on the western wall of the trench - a bit of the old German fire-step that had somehow escaped destruction. His eyes were shut. Once his lips moved. His mind was evidently wandering back to his native Lancashire, and to his work on the cotton. "It's bloomin' cold i' this 'ere mill !" he said dreamily.

The sun sank between two stunted and shell-shattered trees. I watched it through a gap in the back of the trenches. Yellows and reds smeared the sky-line in a gradually lessening patch, which at last faded out. The stunted trees went with them. I was chattering with cold. My feet seemed frozen - as painful as if they had been squashed under a cart-wheel. Without warning, a German shell whined through the air over our heads and dropped somewhere in the village behind us. It was the first of many.

"That's Fritz beginning his evening 'strafin’ ' said the corporal. "Come on, lads. Time to get a move on!"

The patient was silent and motionless on his stretcher. The corporal scrambled again up the side of the trench, and again lay on his stomach on the top. Two minutes or so he waited, and then he stood upright. A bullet might have pinked. him at any moment. But none came. Instead another shell wailed through the air and on to the village below. We heard the solemn "crump" of it as it exploded. "Now, boys," he said, "'ave yer gas-masks ready. We don't want to be messed up fiddlin' for them things when a 'stinker' comes over." Then he looked over his men, and said: "Stuffy, you come along by me up 'ere, and the other lads will heave the stretcher up to us."

Stuffy," without a word, scrambled up the trench wall and stood by the corporal. The other four between them lifted the stretcher front its ledge and high above their heads. The corporal and "Stuffy" took the handles front their uplifted hands and bore the weight of the stretcher till two of the lifters had scrambled up.

"You others had best go by the trench," said the corporal. "No use a whole army corps walkin' about in the open. Meet you at the 'aid post.' And with that the four of them and their burden moved on over open ground in full view of the enemy, relying on their luck and the twilight to preserve them. Every day and every night those plucky regimental stretcher-bearers do the like.

The trench opened at length on to a narrow road cut through a hill, and called the Waggon Road. By this road you reached the village below - the newly-captured village of Beaumont-Hamel. It was a village no longer. Every building had been razed flat by shell fire, and such habitations as remained were old German dug-outs underground. At the entrance to one of these was a rough sign-board which, in white letters on a black ground, proclaimed the name, "Mannheim Villas." A pennant, which in daylight showed its colours red Regimental and white, fluttered above the signboard aid post as the mark of an ambulance-station.

This was the regimental aid post. Every regiment has one or more just behind the line at some spot which is sheltered. ‘Sheltered’ is largely a figure of speech, however, for though the regimental aid post is, perhaps, out of the line of direct rifle fire front the enemy trenches, it is in the way of all the shells that are going. Shells were drop ping now about Mannheim Villas, and dropping so unpleasantly close that I, for one, was only too glad to leave the upper earth for the cover of a dug-out.

You entered Mannheim Villas by a flight of wooden steps (twenty or so), sloping downwards steeply front Waggon Road towards the hill out of which the road was cut. The dug-out ran under the hill parallel to the road, and at intervals there were stairs and flue-holes leading upwards from it to the road, and meeting it at right angles. The main passage of the dug-out must have been nearly fifty yards long, but it was not all on one level, and one ascended and descended stairs in most perplexing fashion.

Our patient was lying in the "dressing-room" at the foot of the first flight of steps front the road. The four stretcher-bearers were sitting on the floor breathing heavily. Here the dug-out was about ten feet wide and seven feet high, and lined throughout with stout planks. Vertical beams supported the roof, as in a coal-pit. A lamp and several extra candles, lit as soon as the patient had arrived, shed a not too bright light over the curious scene. To the right, at the foot of the steps, was the dressers' table, covered with a spotless white cloth, on which lay dressings and lotions, basins, swabs, scissors, and all the rest of a surgeon's simpler accessories. In a canvas sling in the roof overhead were splints of all shapes : crooked splints for arms, straight splints for legs, splints in all sorts of fantastic shapes to suit any injury, and all ready to the dresser's hand. Warmth came front the fire under a great cooking-copper built in with cement.

A crowd of muddy R.A.M.C. men and regimental stretcher-bearers looked on as the dressing was done, for beyond this room were their quarters, and, with the shells flying outside, everyone who had no work out of doors was underground The landing of the shells sent a curious, shivering shock through the dug-out but, thanks to its depth and solidity, they did no great harm. Shrapnel and flying shell fragments could find no way down here unless they came down the stairway, and that would need a specially unlucky shot.

No one took the slightest notice of the shells. I watched the faces, thrown into fierce lights and shadows by the flickering illuminants, and as "crump" followed "crump" outside not an eyelid flicked. I doubt whether the men were even conscious of the noise. Night after night of shelling had 'made them disregard it.

The patient's dressing was now finished, and his stretcher was put near the stove so that he might get warm before going off on the next stage of his journey. As he lay there, a young mud-stained soldier came running in a great hurry down the steps of the dug-out. He did not notice the stretcher in the shadows near the. boiler. "Has Private Oldham gone oft yet ?" he gasped. And, without waiting for an answer, he added breathlessly: "Is 'e bad? Where's he going to ? What's his…."

Seeing several eyes upon kint, looking as though for an explanation of his eagerness, he explained as follows : "Oh, there's nothing amiss, but I'm 'is pal, you see, an' I thought I might 'appen to see 'im afore 'e left." He paused for breath, and went on: "The lieutenant let me come down. Sent me with a message to the colonel 'e did … so as I might drop in at tile aid post 'ere on my way. Another pause, and then : "You see, I didna know as he were wounded till quarter of an hour ago. Th' chaps told me, an' I went to th' lieutenant right away " Another pause. “You see, I'm 'is pal!"

The lad could not have been more than twenty, and he stood there in all his mud, with the lamp-light glinting into his bright eyes, coming ever back to that simple soldier formula, "I'm 'is pal," as though in those mystic words lay explanation enough for any queer thing a soldier lad might do concerning another. And in those simple words lies, as every soldier knows, explanation enough for many a risk, many a kindness, many a sacrifice, many a heroism between one soldier and another. There is no truer, cleaner thing in all life than these "palships" of the trenches.

The lad could see that his explanation satisfied everybody - for all of them were soldiers, and knew - and he began his questions again. "Was 'e bad? 'Ow long's 'e been gone? Where's 'e gone to? " The men grinned. The boy looked round to try to see where the joke lay. A voice came at that moment from the shadows near the boiler-a voice singularly sturdy and strong. " 'E ain't gone no-wheres, 'Arry Droilesden," it said.

" 'E's 'ere !”

The voice was too well known. The boy went along the dug-out in a few quick strides. Having reached his chum's stretcher, he looked at it and his: friend stolidly for a moment, and then came the following conversation :

'Ello, Jack !’

'Ello, 'Arry !’ (Long pause).

‘You been and cotched one?’

‘Ay ! l cotched one all reet.’

‘You 'ave an' all? Is it a bad 'un?’

‘Oh, just tidy like."

That was all. From that moment John Oldham might have been to Harry Droilesden the least interesting person or thing in all the Somme battlefield. They did not talk; they did not even look at one another. After standing for some time idly looking round the dug- out, Harry sat down on the ground near John's stretcher. Now they will talk, thought I, - But no. Harry had merely sat, it seemed, the better to scrape mud from his puttees with. the jackknife which he now produced for that purpose. Possibly they spoke later. I don't know. For an R.A.M.C. captain took me away at that moment to be shown over the dug- out. I would rather have stood in my corner keeping a quiet eye on the strange meeting of Harry and John.

We went down another flight of steps and thus into the main tunnel of the dug-out. Here, as "upstairs," the walls were solid timber-lined. There were lamps at intervals. Men were lying on the ground, some of them writing, some card-playing, some reading. We stepped over outstretched legs as we walked along. Then the tunnel ascended by ten or twelve steps and became rather wider. Here were a number of men lying and standing in the neighbourhood of a big brazier filled with glowing coals. The smoke, or rather some of it, left the dug-out up a long sloping shaft to the right, which in the dug-out's German days had been an extra entrance. But a shell had upset the wooden staircase, and the passage bad been remade into a chimney and ventilating shaft. Farther along the tunnel in a little cubicle on the left no bigger than a good-sized packing-case were three officers, two of whom were playing piquet while the third looked on. A candle stuck on the lid of a cigarette-tin was their only lighting. These were "regimental surgeons," off duty. The Royal Army Medical Corps supplies one or more surgeons to each battalion to be "attached" to that battalion. These officers in turn pick out a number of men from their battalion and train them in first-aid, stretcher drill, and the care of wounded. These bearers go into trenches with their battalions and follow them into action They have all the risks of war and few of the joys of fighting, their duty being merely to collect the wounded from the trench or the battlefield as the case may be, and to get them as far as the regimental aid post. The stretcher is the most usual means of transport if the patient cannot walk, but many a wounded man is brought to the regimental aid post on the back of a stretcher-bearer or a regimental pal.

I noticed at the aid post that some of the bearers were of the R.A.M.C.. while others wore regimental badges. It was explained to me that the aid post. is the point at which the R.A.M.C. and the regiments in the line link up, for at the aid post the wounded pass definitely from their regiment - which knows them no more until they are cured - into the hands of the R.A.M.C. who are responsible for all future treatment. In calm times the R.A.M.C. do not go nearer the line than the aid post, but when any fighting is going on they go forward to help the regimental medical workers. Thus, at all stormy times, the R.A.M.C. are sharers in whatever risk is going at the moment, and the number of men of this valiant corps who have lost their lives is testimony enough to what these risks may be.

The officers are no safer than the privates. For though it is an order that medical officers must expose themselves as little as possible, they may be called up into the line at any moment to deal with an urgent case that cannot be moved without surgical treatment.

Every one of the surgeons in that aid post was well acquainted with the trenches at their worst, and, for that matter, the aid post itself was anything but a haven of safety. The hurtling shells outside reminded one of that.

We arrived back at the dressing-room of the dug-out and found John Oldham ready for moving. A runner had been sent to the "motor-car station" to tell them to send a car forward to the motor control, and the patient was to be carried down to the control to meet it. For it was impossible to bring a motor-car so far forward as the aid post. The road from it was no more than a rough path, made with bricks and planks across a wilderness of shell-holes and hummocks. The battered houses of the village had yielded the materials.

We set off, and I noticed with misgivings new shell-holes right alongside the track on which we were to walk. They had not been there half an hour earlier when we passed along the track - of that I was certain. It was dark now - pitch dark save when star-shells rose slowly into the sky from the German lines behind us, throwing for a few seconds a pale, sickly whiteness over a great circle of earth.

An eerie thing it was to walk here in the dark, picking your way by tapping with your stick the broken bricks of which the road was made; then, suddenly, to find the whole world lit up as with a ghostly moonlight. Each light stayed only long enough to reveal the grim signs of war immediately about you. It might be only the stretcher-bearers whom you noticed in their queer iron helmets - making still queerer shadows - all marching in step, with their stretcher and its silent burden, rocking rhythmically up and down to each step they were taking. Or a flare might disclose to you the barren countryside, all shell-heaps and shell-holes, with here and there a tree disfigured by shell till its few remaining branches, broken short, stood out hideously, like gnarled, rheumatic fingers clawing greedily at an unreachable sky. Once a flare revealed to me what I thought at first were figures of men sleeping out in the open. But their poses were not those of sleep. Legs, top-booted, stretched out sprawlingly from under stiff-looking greatcoats; arms reached out unnaturally to clasp distant clouts of clay; and a sleeper's head might lie in a pool of water and trouble him not at all. For they would never wake up, those sleepers. The little round caps they wore showed them to be Germans.

After going about half a mile. along that road I saw, some twenty yards off, the red glow of a cigarette upon a face behind it: A man was leaning, smoking, against a motor- ambulance which was hiding under a bank, without lights. This was the nearest point to which a motor could approach. the trenches. The driver stood by while the R.A.M.C. men opened its back canvas flaps and lifted the stretcher into the dark body of the vehicle. "Will you ride in the van or do you care for a walk?" asked my guide, an R.A.M.C. captain. I was anxious not to lose touch with the patient, but on being assured that I should overtake him at the. next stopping-place I agreed to walk. One man got in the waggon with the patient, the others stood by to see him start away. "Good-bye, Jack,". said one of them to him as the engine began to turn. "Hope it's one that will take you back to 'Blighty.'" The speaker was Harry Droilesden. With this good wish - the best wish you can wish any wounded British Tommy - he drew off and turned once more with the stretcher bearers towards Beaumont-Hamel - Beaumont-Hamel with its mud and its shell-holes and its dead. For myself I was glad to be leaving that war-shell-range worn spot and all its dangers behind me.

I said something of the sort to the captain, adding that adventures and dangers and risks were the pleasantest things in the world - when they were well behind. you and you were through them. I even found myself stepping out with vigour, under the stimulus of this idea of danger faced and at last successfully passed.

which showed with a faint pale-green light in the darkness. "Yes," he went on. "They usually begin shelling for working-parties about this time, and you never know quite which district they'll pick upon.” He explained that both sides did most of their work in the trenches such as trench-digging and repairing, dug-out making, wire-laying and so on at night, and that working parties were sent up from villages - and camps behind the lines to do it.

At night, therefore, the Germans began to shell these villages and the roads leading from them in the hope of hitting working-parties while they were assembling or were moving up to the lines along the roads. "They might begin any minute to drop them on this road," he concluded.

I pulled my shrapnel helmet till it hung more protectingly over the nape of my neck, and walked on with my enthusiasm distinctly modified. Five minutes later, as we plodded along that dark, uneven road, the shelling began sure enough. But the spot which the enemy bad chosen that evening was not our own immediate neighbourhood - but the village to which we were walking and to which John Oldham and his motor-ambulance had gone on. This was the village of Mailly Maillet. It lay a few miles before us, and the German shells on their way to it passed over our heads. We could hear each of them, first behind us, a thin piercing whine which gradually rose in pitch and grew louder as the shell passed overhead, then grew faint again. A second or two later we heard the boom of the shell's explosion in the neighbourhood - of Mailly Maillet. Some shells, we noticed, passed over without being followed by any "clump" from the village. We heard the explanation later, which was that a number of them were "duds," having failed to "go off."

I am afraid I loitered just a little on the road to Mailly. One excellent excuse I found for doing so was to turn aside to see the motor control post. It was a ruined homestead by the roadside, the roof of which had been patched up with tarpaulin sheets and the walls with sand-bags. Thus repaired, it made a quite presentable - shelter in spite of all the German shells had done. A man with a rifle and a lantern bawled : "Who goes there ?" as we approached in the darkness.

An R.A.M.C. sergeant was in command with one or two helpers he arranged for of ambulance-cars between Beaumont-Hamel collecting post and Mailly Maillet behind, and for any extra cars that might six to one be summoned by runner. In a little book which he showed us by lamp-light he had the time of the runner's arrival and the time the car was despatched.

Apparently the most advanced posts of the field ambulance organisation had not attained to the luxury of a telephone service yet. But seeing that even the gunners had all their work cut out to maintain telephone lines over these shell-swept areas, a telephone corps for the R.A.M.C. was probably too much to ask for.

We came out into the darkness of the Mailly road again to find that the British guns had taken up the challenge of the enemy's "strafe" and were replying with rather more energy than. the enemy was showing. I gathered in fact that the British policy of retaliation at this period of the war was grossly generous, the general idea, both in battery and in trench being to send back six times the quantity of whatever the Germans sent over. Thus, if any German infantryman in a playful moment pitched up a hand-grenade to drop into your trench, the scheme of things was promptly to throw six back. Should a German gunnery officer, to gratify a whim or a visitor - as I myself have been gratified by gunnery officers, - who as a genus just love to say: "This is how she does it," and then to fire off their biggest gun, much to the shock of that visitor's ears and system - well should a German gunner give way to such weakness, the British gunner felt in all politeness bound promptly to fire off six shells as big or bigger and if he felt particularly active that night he would not stop at six times. Another little disinterestedness about the British gunners that struck me was this - that none of them seemed to throw work on ‘the other fellow’. Thus if six shots or so were needed to keep up the fair proportion of six shots for one shot sent over by some chance German battery, every single battery that heard the shot seemed to think the task of answering was its own especial prerogative and not that of "the other battery" round the corner.

It is only in this way that I can explain the extraordinary response given to those score or so. of German shells that flew over our heads on the Mailly road that night. Every British battery for miles around seemed to have awakened from its slumbers by those shots, and to be working now like a railway breakdown station gang for vigour. Batteries to the right of us, batteries to the left and in front of us, all were barking away in wonderful fashion.

The white-blue flashes of field-guns and long. guns, the pink flashes of "hows" - as howitzers are called-lit up the earth. To add to the sky effects the Germans, becoming nervous of an attack, perhaps, began to send up star-shells and flares in great quantities.

To stand thus, in a quiet country lane, hearing the amazing barks of many different guns and the whine of many different shells, and to see gnarled and shattered trees jump out at you, black and still and horrible against momentary backgrounds of livid flame, struck me as the most unreal thing I had ever experienced. But for one's ever-conscious knowledge of its full horror and deadly reality, one would have thought it all a product of stage-craft rather than of war.

From among the mud and ruins of Mailly Maillet-which had-suffered from the gun fire of British, French, and German alike in its day - my guide picked out a little house with whitewashed walls, standing alone in a ruined garden. Every window of the house was broken, and curtains of felt or flannel, fastened only at the top, had been hung inside to cover up the wooden window-frames. If you watched these curtains closely you would notice that they flapped with every gun that was fired in the neighbourhood and with every German shell that arrived in the village.

The house had escaped major damage. A chimney-pot or two -had been hit and there were jagged chunks out of the wall in one or two places; but little else. The one great German shell that would have "done for" that place and demolished it entirely had repented at the last moment and failed to explode. It lay on the little backlawn for all eyes to see by day and for all shins to hit by night - a "dud." You fell over it when you walked into the back garden at nights. It was the usual thing, in fact, for your. host in that house to say, if you spoke of going out of doors for a breath of air at nights: "Don't fall over the shell.'

That house was an Advanced Dressing-Station, an important link in the medical scheme of things out at the war.. Its commanding officer was the captain who had kindly acted: as my guide to Beaumont-Hamel, an excellent soul from far New. Zealand.

"Now, this advanced dressing-station," he had begun, when we entered, “receives wounded from its regimental aid posts at Beaumont and -. But I won't tell you another word till you've had some tea, so you can put that notebook away for a spell and - “WAIT !" - this last word in a shout. I thought he was joking still, but a rosy-cheeked orderly put his head inside the door and said; "Yes,: sir:?" - Tea was ordered, and I made the discovery - that the orderly's name was Wait.

"Your patient, Qldham, is safe and sound in the cellars," the captain added, "and will not be going farther for an hour or so, so you can put your mind at rest. He won't escape you."

"Why in the cellars ?" I asked.

“Because," he answered, "Whenever the village is being shelled, as it was when we came in, all the patients we may have in here at the. time are carried down into the cellars. They'll come up again when it's over. Get some tea.” The captain had poured me out a tin mug of tea from a tin teapot. Toast had come in on a tin plate, and butter lay near at hand in a tin can.

“Milk, orderly !" sang out the captain.

"I'll have to get some more out, sir," said the orderly, and the - er - the gentleman there is sitting on it."

The upturned-wooden case which served me for a chair was rummaged in and from it was produced a tin labelled “Milk." The orderly jabbed the spike of his jack-knife clever]y through the lid in two places, one on each side and when he upturned the tin over my tea mug there flowed milk from the lower hole, excellent stuff of the density of cream, while through the upper hole of the-tin lid went in air to take the place of the milk that came out. The day of thick and sticky canned milk was over.

Over tea and toast and jam I had time to take stock of the queer room in which we sat. It was the captain's bed-room, sitting-room, dining-room, reception-room, and office all in one. The walls were of plain, whitewashed plaster and the windows - or rather the window-holes - were covered with sacking, which flapped listlessly in the wind and heavily at every gun shot or shell fall outside.

The one lamp of the place stood in the middle of our tea-table. Its glass mantle had been broken and repaired - very dexterously, I thought - with surgical sticking-plaster. Its flame threw firm, black shadows of you on to the whitewashed wall behind. Some busy soul had occupied himself in tracing out these shadows of men as they sat at the table, and the wall was covered with charcoal silhouettes. One aquiline portrait was labelled.: McMurtrie," another was labelled " Torrance" - former- occupants, no doubt, of' this primitive little billet. The captain's camp bed lay in a far corner among some boxes of tinned milk, petrol-cans, and other stores. A bright fire of wood flickered in a rusty little grate, sharing about equally with the plastered lamp the duty of lighting the room.

After tea I found John Oldham again. He was in .a cellar, with low-arched roof lying on his back on a stretcher under a blanket, just above the edge of which appeared the glowing tip of a cigarette and his face.

"How goes it now?" I asked him. He grinned and said in a voice full of mock woefulness: “Well; Ah'm just about as well as can be expected, thank ye, sir."

Other patients lying on their backs on the cellar-flags near him all laughed at this, and I gathered from a friendly corporal that this was the recognised reply of Tommies who while feeling in pretty good spirits, were anxious not to be regarded as well enough to be sent back to: the trenches. For a little hospital treatment, even in the dark cellar of a shelled villa, came like a spell of paradise to lads who had been weeks in the dreadful trenches of the Somme. Not that Oldham, with his thigh wound, ever stood any risk of being sent back. Still, it pleased him and his sense of mischief, as active in him as in all good soldiers, to pretend that he was shirking going back. It was one of the forms of humour at the front to pretend to be "funking" or shirking. As they lay helpless I could hear them joking one to another about their illnesses and wounds. I remember one big fellow, whose face had been half blown away by a shell and who, when he thought no officer was about said, in a mock, pathetic voice for his fellows to hear : "I think I could just take a little gruel now, doctor." And then he himself and all his pals laughed as at a joke of priceless merit - the truth being, of course, that if he did manage to eat even a little gruel that would be all that he could manage.

But that same spirit of fun-making seemed to hang about some of our British wounded even to the end; they died mocking their wounds.

As soon as the shelling stopped the patients were carried to more airy quarters upstairs. The change was no doubt welcome enough, for the fire which had been lit in the cellar to take the chill and dankness for the place was behaving badly and sending more of its smoke into the cellar than up the chimney. The orderlies were coughing heartily enough, but the patients seemed not to notice it.

The Somme had apparently made any other conditions seem comfortable. The stone steps leading to the basement had been covered with a smooth plank and up this inclined plane the patients' stretchers were slid with greater ease and steadiness than would have been possible if they had had to be carried. "It's as good as th' toboggan at Blackpool," said one voice; and from the voice and the accent - which made "pool" rhyme with the word "foal," as a Piccadilly "Johnny" might pronounce it - I recognised friend Oldham, of Lancashire.

From the cellar the patients, who numbered perhaps a dozen, were carried to more airy quarters in the attics. Here they lay anxiously speculating as to their fate. Would they be kept here for a day or two and then sent back to the trenches, or would they be passed on to a base hospital or to "Blighty" ? This last was what every, man hoped for; but of course for all of them it was impossible. Slight cases of injury or sickness would lie here perhaps for a day or two and then go back to duty. Others might go only a little way down the lines of communication, there to lie up till better. Others might get as far as the sea-coast of France to one or other of the base hospitals. Every type and condition of hospital in fact, between 'the trenches and home would sift out some patients for treatment and only the lucky few would ever achieve their dream of being sent home to "Blighty" and seeing their friends once more. Once when I went upstairs to have another look at the patients a discussion was going on between two or three of them as to their respective chances of being sent home. They were lying on their stretchers, some smoking and talking, others asleep. A solitary lamp shed a faint, flickering light over their recumbent forms. "Ay," said one voice, as though in disputation over some point a neighbour had raised, "It's true enough that I've only a bullet wound in the arm, as you say, but I've got a touch 0' bronchitis an' all! Heard the orderly say so when he heard me wheezin' !”

"That's all very well," said another voice, "but did he write it down on yer ticket ? You could have hydrophobie also an' it wouldn't help you two-penn' worth if the doc didn't write it down on yer ticket !” (The ticket to which he referred was the little label - white for non-dangerous cases, red and white for dangerous cases - which was tied to the jacket of every patient at the regimental aid post and which with any necessary emendations or additions made at intermediate dressing-stations, went with the patient from first to last as the medical summary of his case and symptoms.)

"'Can't say as it's on my ticket as I' knows on." Here the voice was raised to call to the orderly who was not far away: 'Hi, matey, you might read us out what's written on my ticket !”

"Wait till daylight and get to sleep my lad," said the orderly not unkindly. "It's latish. You ought all on yer to be getting a bit 0' sleep instead of chattering away there like a girls' school. Be good lads an’ get to sleep."

He reminded me of a mother. There was silence for a while in the little whitewashed attic and then the voice went on in a whisper : "Yer bronchitis will be a good help if it's' on yer ticket. We'll read it in the mornin'. My chance is pretty all right, I think. I've got a temperachure, besides me wound. 'Undred it were when it were last took. Pretty good that! They think a lot about temperachures. Orderly told me so. Very particklar about temperachures." So they talked, on their stretchers, in that dimly-lighted attic. Oldham, I noticed, was asleep.

I went downstairs again and into the room opposite the doctor's. This was the receiving- room and dressing room; a big Primus stove sent up a dull droning from a point near the empty fireplace. ,By lamp-light a surgeon was dressing a dark-red gash in a man's back. Another patient waited near, sitting on a form. Very interested he seemed in all that was being done to his colleague. He caught an orderly's eye and speaking with difficulty through a swollen mouth, he explained his case. "Small tube blew out of our gun. Got me fair in the teeth it did, and laid out a tidy few of them on the floor. Guess I'll have to have a nice new set of top ones from the dentist when I get home. Fancy me wi' a nice set 0' false teeth. Won't I be a swank !" .And he laughed at the prospect.

A huge box stood in the middle of the floor and every now and again the dressers' threw into it bits of wound-stained lint. With these grim tokens of war and casualty it was full. "We empty it once a day in slack times, said an orderly, "and three, four, five, or even twenty times a day in busy times." I noticed that one of the treatments meted out to all wounded dressed at this station was a hypodermic injection of some white-coloured, fluid. This was to guard against the deadly disease tetanus, or lockjaw, the germs of which live and thrive in the yellow mud of the Somme. As it was almost impossible that any wound incurred in this district could have escaped contact with mud, the anti-tetanus injection was given in every case.

John Oldham was sent farther down the line that night, and I went in the same motor- ambulance with him. It was 'moonlight now, and the gun fire had ceased, though an occasional star-shell soared into the air and whitened the sky over in the 'direction of the German lines. The roads were quiet. At first we talked - he lying on his stretcher on the right side of the car, I sitting on the seat on the other side. He told me he was a spinner by trade, and that be and many other spinners had joined up at the beginning of the war in a Pals' battalion .recruited in the neighbouring city of Manchester. He went on to tell me of his pals, and what had happened to them and of the places they had been in on the line.

But, sitting there in the darkness of the ambulance-waggon rocked by the lurches of the car on the uneven road, he seemed to tire. His voice became more of a monotone, and I ceased to answer any of his remarks; and sure enough before many minutes he was asleep again. I turned aside the back flap of the car and looked out. The moon, though hidden now, was sending a soft luminousness over things. Now and again we passed a soldier in an iron helmet plodding along the road. In one ruined homestead without roof, was a tiny fire round which three or four soldiers were sitting. The earth round about was strewn with barrel-shaped coils. The spot was a barbed-wire "dump."

Once we passed a little train of supply-waggons, empty and halted by the roadside. A lantern glowed under each tarpaulin roof, showing that each was in use as a tent or shelter. From one waggon, in passing, I saw the faint, blue light of a Primus stove. Between. the two sides of the waggon were frames of wood with sacking stretched tightly across them to serve as beds.

Sentries and military police with lanterns were posted along the roads at intervals, but they did not trouble us much. Our driver and his car-which did this particular run many times a day were too well known for them to need to stop us. And so, in good time, we arrived at the next halting-place for wounded from this particular part of the Somme front. It was a main dressing-station in the village of Bertrandcount.

Switching sharply to the right, our car passed tinder a brick archway and into a big open square. It had been the yard of a farm, and was flanked on all four sides by low farm buildings - those curious buildings of bricks and beams and plaster common to all the farming villages of the Somme. In normal times that farmyard at this time of night. would have been dark and quiet, save, perhaps, for the lowing of cattle in the byres. But now dim lights twinkled from every side of the square, and uniformed men, some carrying lanterns, were moving busily about.

A little squad of R.A.M.C. orderlies came at a trot to meet our incoming car, and as we came to a standstill they formed up in line at our back without question or word; each man ready to make things easier for any poor wounded lad that might be inside. As the canvas flap of the waggon was pulled aside I stood up and leapt out, but before I reached the gr6und stout arms caught me suddenly under the armpits and lowered me to the ground as gently as though my twelve-stone weight had been twelve pounds.

"Take it gently sir," said a reproving voice, "you might 'appen to do yourself harm if you don't go gently." In the dark they had mistaken me for a wounded officer - as was natural perhaps seeing that I was riding in an ambulance-motor and that my uniform was that of an officer. I may mention now that on all my journey from the front to home R.A.M.C. men of all grades showed the same inclination to treat me as an invalid. I had to explain to them that I was neither wounded nor ill, but even then they would sometimes look me over carefully for a casualty card or ‘field medical card’ as it is called. Some of them seemed disappointed that they could do nothing for me and the way they leapt away to help any wounded Tommy or officer was evidence enough of their real keenness.

The commanding officer of this main dressing-station - an R.A.M.C. colonel - had himself come out to see what cases our ambulance-car and others behind it had brought along I made myself known to him, and presented my credentials. He took me with him while he saw to the disposal of the cases, and then said I must have something to eat before I looked over the station in more detail.

Along a muddy lane we plodded to a little white cottage by the door of which were painted the words "Officers' Mess. Field Ambulance. No.-"

In a plain kitchen, some half-dozen officers were sitting round a rusty fire-grate before a fire which shed a thin fog of smoke into, the room. A lamp-light shone upon the remains of dinner - for dinner, late in this busy camp was just over. I made there the acquaintance of officers some of whom (as I learned later) had given up medical practices and positions at home to come out and "do their bit," and it was no rare thing to see streaks of silver in the hair of an officer wearing the modest two stars of a lieutenant. An orderly of size and venerable age found me some mutton and cabbage on a tin plate, and, in a confidential whisper asked me whether I would like, whisky-and-water or tea. I have noticed before in Canada and elsewhere how hard work in. primitive conditions conduces to the tea habit. When I remarked something of the sort to the colonel he mentioned that almost the only drink and the only thing asked for by the wounded men and sick who came up from the trenches was tea. "They are offered cocoa or coffee or soup, or a hot meat-drink of some kind, but almost all of them," he said, ask for tea."

"It's a curious thing too," added the colonel, as we walked down the lane again to the station later, that they won't eat meat. At first, when they come in muddy and tired and weak, they don't seem to want anything much, but a mug of hot tea brightens them up, and then they feel they can eat. And what do you think they like best ? Bread-and-jam! Wounded Tommies who will not look at sandwiches or meat-stew or anything else will eat ravenously of bread-and jam. My own belief is that you can't do better for a wounded man, especially walking wounded, than feed them up, and I have watched a good deal to see the thing that they like best. Bread and jam comes an easy first."

By this time we were in the receiving-room of the dressing-station. A barn had been provided with a canvas roof and partitions and also with a big waterproof ground-sheet for a flooring. Acetylene lamps gave quite a good working light and the chamber was kept at a pleasant warmth by a circular stove, the flue-pipe of which passed through a tin panel let into the canvas sides of the chamber. This tin-plate flue was no more than a petrol-tin cut up and flattened out-struck me as an ingenious way. of overcoming the risk of a fire in the canvas wall due to a too hot flue-pipe.

The first thing that happened to every wounded man who entered that reception chamber was to have details taken .of his name, regiment, wound, and conditions as shown on his little field medical card, and after that to be fed, washed and tidied up and given new garments if necessary. Most wounded were able to walk and they were told to pass over to the refreshment buffet, which with a bright light of its own stood in a separate partition under the presidency of a cheery-faced orderly in shirtsleeves and a white apron. Before him was a counter filled with eatables. His opening question to each man was this: "Now, my lad, tea, coffee, cocoa, soup, or stew? " It might have been all one word and one dish by the businesslike way he rattled it off. But the Tommies understood all right, and one and all chose tea. As he filled mug after mug it struck me that he did it more by his sense of touch and weight than by sight, for his eyes were roaming about all over the wounded and his lips were repeating again and again the cheerful invitation: "It's all right, my boys, pick up anything you fancy. It's all yours and it's there to be eaten." And with his eyes and a nod of the head he would beckon to any soldier who seemed to be hanging back and press him to choose something from among the great platefuls of sandwiches, bread-and-butter, bread-and-jam, cake and so on which filled the counter. The artillery man with the damaged mouth mumbled, on being pressed to eat, that he could not eat anything because of his sore jaws, whereupon the attendant said: " Oh, I'll soon fix you." He busied himself behind the counter for a minute and then presented the artillery-man with a basin of hot bread-and-milk.

The stretcher cases lying in another canvas partition were feeding or being fed by orderlies when I went in to see how friend Oldham was getting along. "Just had a cup o' real good tea," he said cheerily, "and now I am going to slip my face round this." And he held up for my inspection a big slice of bread-and-jam. "Makes you hungry motorin'," he added quite seriously. My mind went back to that solemn and jolting night ride of ours in the darkness of the motor-ambulance car, and I thought I had never heard the word "motoring" more curiously applied.

There was to be no transport of wounded that night to stations farther down the line, and when I left the main dressing-station for the officers' mess again the patients had been "bedded down" for the night. The colonel had taken me round various dark canvas wards, with an electric pocket torch to light us, promising me a more detailed "look round" in the morning, and I walked up the lane with him to the mess with curious memory pictures going through my mind of recumbent figures of wounded men in all positions - pictures of men with placid faces, calmly sleeping, of men with faces furrowed by pain, of men lying with bodies bent and limbs awkwardly extended - and all these pictures were cut out in circles from surrounding blackness by the white glow of a pocket torch. It was as though I had been in a dark room, watching lantern slides on a screen; circular slides showing poor wounded, bandaged, and "splinted" humanity in vivid lantern pictures.

I slept that night on a camp bed in a cottage in the village. There had been some discussion in the mess earlier as to where I should be billeted, and someone had said: "In the padre's billet." The padre was away on leave it seemed, so I was given his bed. They took me along a muddy lane, then through a gate in a wall and up a garden path to a white, low-roofed. cottage. In a ground-floor room, littered with ornaments and furniture and luggage, were two soldiers' beds. By the light of my candle I could see that a man was already asleep in one of them. Upon the other, a few inches above the wooden floor were some blankets and an officer's greatcoat. Three stars on a black ground. on the shoulders told me that it was the padre's. May I thank. him now for the comfort of his greatcoat that night. For it was bitter cold.

I did not feel like sleep. For a time I lay awake with the candle on the floor near my face, watching the flickering shadows it threw upon the whitewashed ceiling. Everything was quiet save for the ticking of a watch somewhere in my neighbour's clothes and the quiet moaning of the wind in the wide chimney of the cottage. Then he began to breathe heavily, and in a minute a loud voice came to me from his bed, saying: "Look here, you'll have to get those waggons into better shelter than this, and quick, too."

"Sorry, what's that you say?" I replied. He did not answer. He was asleep. I. learnt next day that he was an officer of motor transport. His cares were evidently following him in his dreams.

At length I seized my boot, and with the heel of it knocked out the candle, trying then to sleep. But after perhaps ten minutes the solemn "crump" of a shell somewhere in the neighbourhood made me wide awake once more. I listened for another. It came along, and though it was well distant the cottage and my bed gave a little shiver. There came another, and I felt certain I heard the fall of a "dud" shell in the near neighbourhood of the cottage. I felt for the candle and found it, but there were no matches I got up and searched but could find none. The room was dark. Feeling my way I found the door, went out into the passage and opened the front door. A cold wind rushed in. Here in my pyjamas I stood watching the restless swaying of the bushes in the garden and the white flashes of guns and star-shells in the sky away to the east. There was not a sound in the village of Bertrandcourt ; not a light. The moon, behind banks of clouds, cast a filmy pale-blue light on the white walls of the cottage. If shells were causing those dull, flat thuds that I could hear every now and again, certainly no one was taking any notice. I went back and crept in among the blankets and the greatcoat once more, and was half asleep when sounds, as of a fierce quarrel-in French-and moans came from the neighbouring room of the cottage. For two or three minutes it went on in most amazing and unnatural fashion - all in one voice, till I guessed that here again was someone talking in his sleep - some old Frenchman apparently. infirm and short of breath, for he gasped as he talked and scolded.

An orderly standing at my bedside with a candle woke me next morning. Then he flung back the heavy wooden shutters and let the morning sunshine into the room.

As I stood washing, the door of the further room opened, and out came the queerest old man. He was dressed in some quaint dressing-gown and a little black skull cap, from under the sides of which protruded fuzzy tufts of silvery hair. His head, under the skull cap, seemed to taper almost to a point. He had a round, clean-shaven face, ruddy as an apple ; heavy white eyebrows, and beneath them little twinkling eyes of extraordinary brilliance. As I did not know him from Adam I was not a little surprised when he trotted up to me playfully, and with many smiles patted me on the bare back.

"You Engleeshman? Yes? Very bon," he said, all in one breath. "Germans-Allemands - no bon, no bon." He shook his head fiercely, then he calmly looked me over as I stood there in my pyjama trousers. He stroked my bare arms and went on: "You soldier? Engleesh soldier? Very bon, very bon." He never waited for an answer to anything, but went on: "You marié? You got pretty wife, very bon, yes?" I could not help grinning, and he continued: "Bon, very bon." He passed his hand over my chest and back, then hit me on the chest with his fist.

"You fort, yes? Very strong, very bon, yes? " I replied in French to the effect that I was very well, thank you.

He cocked his old head. on one side. Then he turned, and repeating: 'Very bon, very bon, very bon," he trotted, back to his own room.

I learned later that the old gentleman, was the village curé, very old indeed, though growing. younger in manner every day. It was his cottage in which I had slept. The war had upset. his mind very much, and he was very, very old so, I felt. glad I had not. chased. him out the bedroom with my shaving-brush as I had once thought of doing.

The main dressing-station at Bertrandcourt, seen by daylight, looked much bigger than it had done the night before; one saw that in addition to all its farm buildings, made habitable and usable by canvas roofs, floors, and partitions, it had also many canvas marquees, stretching out into the orchard behind. Here too was a dug-out for “shelly" days, as my guide expressed it, capable of sheltering a hundred patients if need be. This was one of the best specimens of British-made dug-outs I saw on the Somme, and it disposed effectually of the statements one often heard that only the Germans could build dug-outs.

The equipment of the main dressing-station was considerably more extensive than that of either the advance dressing-station or the aid post. Quite extensive medical work could be done here if necessary. One interesting feature was the oxygen tent, in which stood an oxygen cylinder with a cunning little contrivance (made from a petrol-can, a tin bath of water and some tubing) with which oxygen could be administered to half a dozen patients at once from the one cylinder. An incinerator was busily at work in one corner of the grounds making a merry smoke of its own. In another corner were good-sized kitchens with cooks busily at work, As I walked round with the colonel, men were busy improving the pathways between the various tents or wards by laying "duck-boards" upon them. Duck-boards laid on wet and slippery mud make perhaps the most slippery pathway possible - a pathway most dangerous and difficult for a wounded man or for a stretcher-party. But this path can be made "non-skid" by the simple device of laying wire- netting such as is used for chicken-runs over the surface of the wood. This plan had been followed at Bedrandeourt, and the paths were quite safe and comfortable under foot.

Oldham had passed a fair night in one of the canvas wards of the dressing-station, and it was decided to send him on that day to the next medical post on the long journey home - a casualty clearing-station. He heard the news secretly from me with a pleased grin, for it was not always an easy thing for a wounded man to learn whether he was to be moved and what his destination was, In fact, he could be kept at any of these medical posts on the line, if his case was capable of treatment there and if there was room to spare - and eventually he would be sent back to his regiment without ever getting nearer to the one great place he hoped to go to "Blighty." Every move farther down, therefore, was regarded as a "score." The parties of wounded leaving any medical post for the one lower down were all smiles and good-humour. They would be that much nearer "Blighty”.

One point interested me as the big "Bulldog" motor-ambulance car was being loaded up with its freight of wounded. The driver was signing his name in a book held open for him by the sergeant in charge of the camp "pack store." The Sergeant explained to me that every article found on a wounded man had to be accounted for on every stage of the journey from trench downwards. Every wounded man's pocket possessions and luggage were entered on printed forms, item for item-knife, watch, rings - even down to simple, valueless things such as "a key-ring without keys," which item I saw figuring solemnly on the list of personal possessions of my friend Oldham. The driver of any car receiving a patient had to give a receipt for any kit and personal possessions of the patients he received. When he delivered his patient to the next medical post he took a receipt from the keeper of that station's pack store, into which they were put pending the wounded man's recovery or removal to another post. In the case of officers all luggage, as well as equipment, had to be signed and accounted for in the same way. The list of a man's belongings had at the first opportunity to be signed by the man himself as being' correct. In the case of an officer his servant's signature was regarded as sufficient. If a man were too ill to sign, then one of his officers had to sign.. Money and jewellery and other small valuables were put in a little bag and tied upon the patient.

Our carload for the journey to the next post consisted of five patients and myself as inside passengers. There were only two stretcher cases - Oldham and a young Scottish soldier who though suffering from. a most painful shell wound, lay quietly on his back smoking cigarettes. The other passengers were "sitters" as walking wounded or sick were called for purposes of transport. Among them, was a young officer suffering very badly from bronchitis. He spent much of the journey apologising to me and himself I think-for having left the trenches. He was ill and so weak that he only just failed to be a stretcher case. He seemed terribly depressed - not so much by his illness as at having to "throw up the sponge," as he termed it, and leave his work. "Stuck it as long as I could," he told me. Then there was silende in the car for perhaps five minutes. I was thinking of something else when he turned to the again and said: "Wouldn't have cared if I could have stuck it till we were relieved." Another pause for coughing, and then: "We'd only another day to go." He made more remarks of like nature before the journey was finished. His failure was on his mind, it was clear.

It became cold as the sun sank, and one could see that the patients tired. The men sat or lay with closed eyes; There was no talking for the last half-hour of our journey. When at last we ran into the casualty clearing-station, beyond Puchevillers, it was dusk. A gang of German prisoners, who had been doing some path-making about the camp, were forming up under their escort ready for the march home to their barbed-wire camp across the fields; our car was unloaded by orderlies, whose first care was to get the patients to the receiving-shed, where their names and particulars were taken, and then on to the refreshment buffet. For the first step towards curing a wounded man at this medical post, as at all previous posts, seemed to be to feed him - very sound treatment, too, so the wounded appeared to think. Within half an hour sick and. wounded alike were snug under blankets.

A casualty clearing-station was the nearest medical post to the battle-front that had something of the permanence and the resources of a real hospital. This casualty clearing-station covered several acres of ground. If 5 buildings were all huts or canvas marquees, it is true, but in them was to be found the most complete surgical and medical equipment, even to X-ray department, pathological department, and the rest. Here also for the first time on the Via Dolorosa which the wounded man followed to get from the front to his home, were to be found women - British nursing Sisters. It was one of the greatest moments of that journey for the wounded Tommy - that moment when he met a British woman once more, perhaps for the first time after weeks and weeks in the trenches with not a soul within miles, either friend or enemy, but men.

The effect which this presence of their countrywomen had on the wounded struck me as remarkable. I watched friend Oldham being carried into his ward. He was tired and inert. As the men orderlies attended to him he lay listless and irresponsive even to pain when they moved him. The lamps were just being lit. He took no notice of anything. Then a Sister came quietly into the ward. At the voice of a woman speaking English, Oldham's eyes opened wide at once; he raised his head from his bed to see who had spoken. Other eyes than his opened too. Of the new patients in that ward there was not one save those already asleep who did not become agog with interest at the sound of an Englishwoman's voice. They followed her about the ward with their eyes. She stood still when her work was done and spoke to the soldier in the bed nearest her. They waited for three or four minutes and one could see the interest of the wounded man in his steadfast gaze upon her. There was a pause in the talk, but he still looked at her. Then feeling perhaps that some little apology for this was due from him, he said : "Do you know you're the first Englishwoman I've seen or heard speak for over forty weeks."

I had a word or two with her later: She was a comely, motherly woman of thirty-five or so. "The Tommies seem interested to find their countrywomen here Sister," I said.

“Yes," she replied, "it's funny, isn't it ? I don't think there are many new patients come along here from the front who don't pass some remark to the Sisters to show that they are glad to see us. They will watch you all round the ward and some of them, if you don't happen to speak to them, will speak to you, just asking you some little question or other. They like to keep us talking. We've all noticed it. Poor fellows, they tell us sometimes that it does them more good than medicine to see an Englishwoman again and I am sure it's not just soldier's blarney you know, because they are so serious and polite to us and tell us about their homes and their wives and mothers and sweethearts. Perhaps it is that the sight of women again makes them think of home and makes them forget for a time the dreadful things they have been seeing and feeling out yonder." She nodded her head in the direction of the German lines, whence the sound of gun fire came now faint and distant.

When Sister had left the ward I walked over to Oldham's bed. I had noticed his interested eye on Sister and me as we had stood talking. "It looks a bit more like civilisation to see an Englishwoman again, doesn't it ?" I said, being anxious to know what he thought of it.

"By gum, it does that there !" he said warmly. "Makes you kind of feel," he said, with pent brows that showed something of his effort to express his thoughts - "makes you kind of feel - " He stopped. He was very weak and worn. His nether lip trembled for a second like that of a little boy and. tears rolled down his cheeks. Poor lad.

An orderly came bustling along with an extra blanket and without looking at the patient's face, he went through several bustling manoeuvres with especial vigour, I thought. " Now you're more in parade order, my son," he said, as he finished. "Give us a shout if you want anything !" I was standing at the foot of the cot looking about the canvas ward, so as not to seem to see the patient's little lapse. The orderly stood by me and with his back to Oldham said in a low voice: "I seen him upset 'isself, sir. They very often breaks down for a minute just when they arrives. I never lets on I sees 'em, but just finds a bit 0' somethink to do about their beds, breezy-like, you know, sir, and you talks a bit to 'em, breezy-like and they pick up in a second. When his wounds is redressed, you won't hear so much as a mew from 'im, no matter how we hurts him. I expect, sir, it's just the hit of 'omesickness breakin' out of them when they're weak-like!”

The point apart from its greater size and better equipment, that distinguished a casualty clearing-station from earlier medical posts on the road home was that it was, generally speaking, on a railway. It was intended for the surgical treatment and the safe housing of wounded until such time as they were fit for sending back to their units, or for transport to some hospital of a more permanent nature. A railway ran alongside the casualty clearing-station of Puchevillers and as I walked round that side of the camp with the commanding officer, an ambulance train shunted slowly into position in the nearest siding, ready to take down to the coast a new load of wounded. It was a train of great length - seventeen long coaches in all - and they were coloured a pale khaki brown and a deep brown, almost black, with red crosses on a white ground coming at frequent intervals on their sides. The train seemed empty, but my guide climbed up to the door of a coach on which were painted the letters "C.O." (commanding officer) and along the narrow corridor inside the coach we met that officer himself coming out to meet us. He wore the three stars of a captain, as did also his assistant, a young man perhaps half his age. The older officer had been a lecturer and examiner in medicine at one of the leading universities of Scotland and now after twenty odd years spent in turning out medical men and officers for the R.A.M.C. he had left this work to come out and "do his bit " as an officer himself. One of the many oddities of his position was that men whom he himself had trained were now in the Service high above him. Some of them had to give him orders-for which in some cases they apologised profusely - still calling him "Sir," as in their old student days.

Learning that I wished to travel in a train down to a "base" with a load of wounded, the train commandant pressed me very warmly to make my quarters with him until such time as the train should start, an offer of which I thankfully took advantage. I spent three days with that train as my home - most comfortable and most interesting days, too.

The train officers' coach was an English railway coach of the ordinary corridor type, but divided in the middle of the corridor by a door. At each end of the coach was a little sitting-room, and towards the centre were separate compartments, used as private bed- sitting-rooms by officers of the staff. The captain and his helper and I had one end of the coach up to the dividing door; the other half was occupied by the three nursing Sisters attached to the train staff. The forty or fifty male orderlies, nurses, cooks, etc., who constituted the remainder of the train staff were housed at the other end of the train. In the middle of the train were the kitchens and administration coaches. All the other coaches were "wards" for wounded and sick. The last coach of the train-that is to say, the one immediately behind ours - was the isolation ward for infectious cases, should there be any. Thus the medical men of the train and the Sisters could visit from their coach either the wounded wards or the isolation ward, whereas all the patients and orderlies were cut off front the isolation ward, unless they visited it by passing through the officers' and Sisters' quarters.

In these small but cosy quarters that night I dined excellently, chatted with the commandant, and slept. Sitting there on a bleak siding in that tiny cabin, with the wind playing shrill little tunes through our ventilators, reminded me very much of being quartered in a yacht lying in some harbour or quiet waterway. Just before turning in that night I did look out of the window half expecting to see water about us; but the moonlight shone only on the quiet siding and the casualty clearing-station round about us, upon the wet canvas tents of which it threw a faintly glimmering sheen like that of shot silk. Once in the night a train passed us, front which came the murmur of innumerable voices and a most curious stamping noise, like the clumsy beating of many wooden drums. I leaned up on my elbow to see what made it. The train was full of soldiers. They were stamping their feet on the carriage floors to keep warm.

On the following day, after a breakfast of ration bacon - which stuck me as the best bacon I had tasted since the war made good bacon impossible for civilians - I looked more closely into that little city of tents and wood huts that formed the casualty clearing- station of Puchevillers. This was one of the normal casualty clearing-stations of our Somme front. There were special clearing-stations elsewhere for special types of casualty. For instance, stomach wounds all went direct from the advanced dressing- station or main dressing-station to a casualty clearing-station specially set apart for stomach cases head wounds all went to another casualty clearing-station direct. Other cases came to a clearing-station of the type of Puchevillers. The size of the place was considerable. It covered many acres of ground, and had its roads and cinder-paths laid out with all the trimness and permanency of a home hospital. There was a wooden pavilion, too, with a piano and a concert-room, from which as I passed it came the sound of a woman's singing. Practising for the camp concert tomorrow," my guide explained.

I looked in at the camp officers' mess that morning and was not sorry I had taken up quarters in the ambulance train; for the officers' mess-room was a tent - into which the cutting wind found innumerable entrances - warmed by one small stove. Lunch was just over and four or five medical men were huddled round the stove having a smoke before going back to their duties. Of what those duties consisted I could form some idea later in the afternoon when the commandant took me into the operating-theatre, a big marquee lit by a blaze of artificial light. Here three operations were being done at once. There were operating-tables for twice as many. The place reeked of chloroform. Three supine figures, partly naked, lay inert on tables. Sitting by the head of each was an anaesthetist, patiently dropping chloroform on to the mask that covered each gently moaning mouth. White-coated surgeons with bare arms and dark rubber gloves were cutting and probing and cleansing away the corruption caused by bullet and shell and bomb; white-robed nursing Sisters stood by with bowl and swab and other appurtenances of this craft ready for handing to the surgeon at even a nod from him.

I walked back from the operating-theatre to my quarters in the ambulance train with my respect-and distaste-for a surgeon's handiwork both enhanced. Poor Oldham was to go through something of the same sort later on but my resistance to chloroform fumes had not been sufficiently cultivated as yet to enable me to stop and see him through, as I had intended.

Rather did I feel that yearning for a cup of tea such as the sick and wounded Tommies felt, and I climbed from the siding into our railway carriage full of hope, for I had caught the passing glance of an orderly carrying a teapot. Alas ! it was going to the Sisters' sitting-room in that terra incognita at the other end of the coach. But I was in luck that day for on entering the commandant's cabin he informed me that I had been invited to take tea with the Sisters that afternoon. He himself took me along and presented me to them - Sister Paul, Sister Mahoney, and Sister Thompson.

Very shyly and very kindly they gave me tea from their excellent brew. This with their Garibaldi biscuits and Scottish shortbread proved an excellent antidote to chloroform fumes and surgical sights, and I found my joy in life slowly returning under their cheery stimulus.

Good, jolly women were those nursing Sisters, practical, natural and friendly as are most British women who have seen life and done things and faced the world. As I sat chatting with them it dawned upon me that, with the brief exception already noted, I had not spoken to an Englishwoman for five weeks, and I realised faintly some of that queer satisfaction which the Tommies showed when they came; after weeks of men and war, to set eyes on a country-woman once more.

The day of the train's departure came at last. A medical transport officer mounted to the footboard of our carriage and announced the news through the window.

“We'll make you half a cargo here,'' he said, “and then you can back up to Varennes for the rest of your load. You'll have something over four hundred in all 'liers and sitters.'