|

|

THE British railways have more than a century of vivid romance behind them ; and in the course of their long period of public service they have gathered together many fascinating specimens of early locomotives and various types of equipment, all of which gain added interest as the years steal by. Until comparatively recently little effort was made to gather together, for exhibition purposes, the many relics of the pioneering days, the valuable examples of locomotives, rolling-stock, and other equipment used by the railways for more than a hundred years. Some time ago, however, it was decided to place on show a collection of railway survivals dating from the time of George Stephenson and his successors. In the ancient Roman city of York—itself one of the world's most famous railway centres—there is open for public inspection Britain's first real railway museum. It is to the initiative of the London and North Eastern Railway that we owe this museum. In its establishment the L.N.E.R. authorities have be en aided considerably by the other three great railways, the idea being that the York exhibits shall not only cover the birth and growth of the L.N.E.R. system, but also be fully representative of railways throughout Britain. The York Museum does not in any way seek to compete with the Science Museum at South Kensington, London. So whole-hearted, however, has been the co-operation of all concerned, that already there is on show at York what is probably the finest collection of historic engines in the world. There are also interesting exhibits, drawn from every period of railway history, of passenger and freight rolling-stock and permanent-way equipment. Before the establishment of the York Museum the L. N. E. R., in common with the other railways, had many interesting locomotive and other relics scattered about its system. These have been taken to York reconditioned, and provided with descriptive labels. The museum, which is admirably arranged, is divided into two sections, one housing large exhibits, such as locomotives and rolling-stock, the other, smaller exhibits.

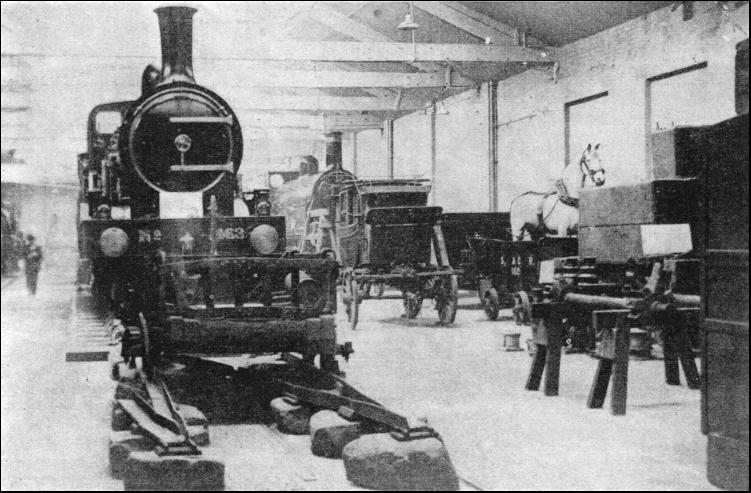

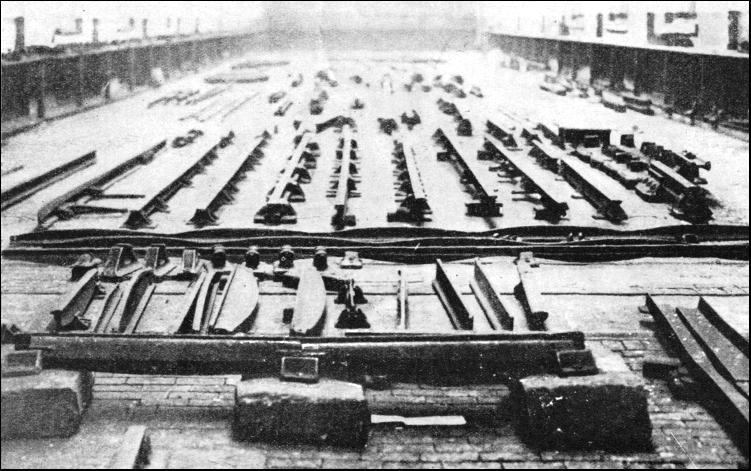

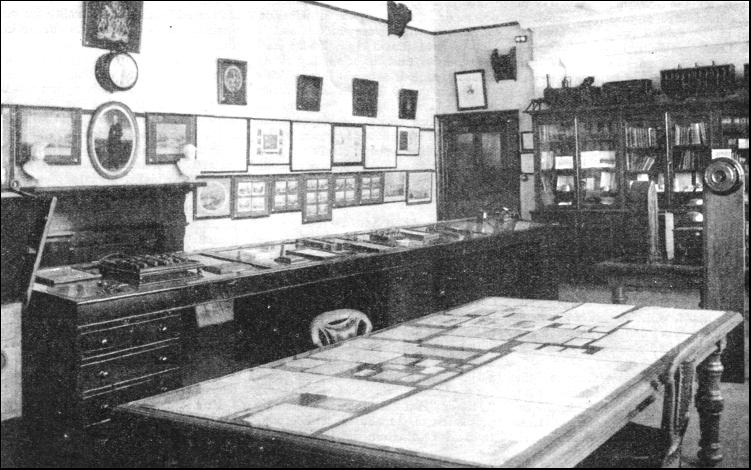

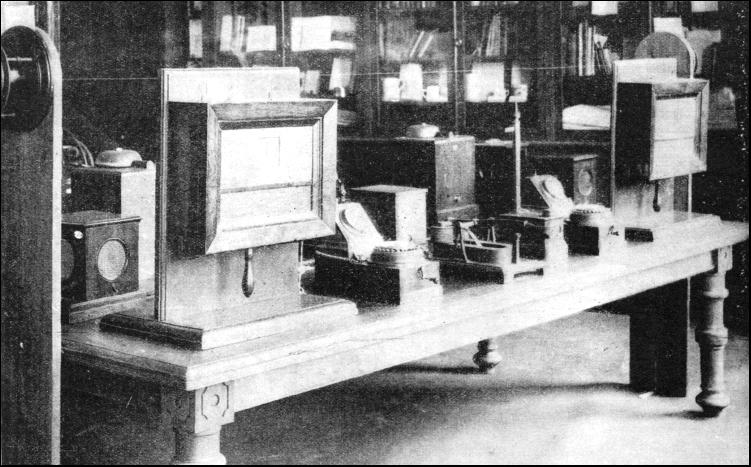

Both sections of the museum are situated within easy reach of the main passenger station. The large exhibits are accommodated in a building that was formerly a locomotive fitting shop, used during the Great War as a munitions works. The main room of the small exhibits section contains prints, photographs, books, timetables, posters, medals, obsolete telegraph instruments, and specimens of early uniforms and equipment. Among the uniforms is a red coat of the kind once worn by passenger guards. This part of the museum also has an example of the goggles which guards used to wear to protect their eyes when they sat perched aloft at the rear of the old-fashioned carriages. A large table in this room contains under glass many interesting documents and curios. Among these is a fourth-class railway ticket and a North Eastern Railway engine-driver's agreement of 1867, in which a promise is made "not to be a member of any union while in the railway service." A print of George Stephenson occupies the position of honour above the mantelpiece. In this section of the museum is another room devoted to a collection of prints and books, presented to the museum by the late Isaac Briggs, of Wakefield. To obtain some idea of the ground covered, let us, in imagination, make a tour of the museum. In the days before railways, travellers who did not own their own carriages had to rely on the "Christmas-almanac" type of mail coach with its prancing team of horses, travelling at an average speed of eight to nine miles an hour. One of the first exhibits we notice at York is the "Rob Roy" coach. This vehicle was bought by the North Eastern (now L.N.E.R.) Railway, after lengthy service as a stage-coach, to serve as a bus during the construction of the railway between Stanhope and Wearhead, in County Durham. Railroad co-ordination is thus by no means new. The exhibits of rails are of great historic interest. There are several authentic specimens of the early iron roads built for wheels without flanges. Especially interesting is the portion of the "Outram Way," with junctions and points complete. This came from the L.M.S.R, Peak Forest Canal, near Chinley. The track was laid by Outram himself in 1797, with cast-iron plate rails 3 ft. in length, laid on stone blocks. The railway was employed to convey stone from the quarries to the canal. The exhibit includes one of the small trucks with flangeless wheels used for that purpose. A later type of rail to be adopted was the channel rail. An interesting specimen of this rail is on view dating back to 1809. Behind the channel rail exhibit are several short lengths of cast-iron bow-shaped rail, an early form of edge rails.

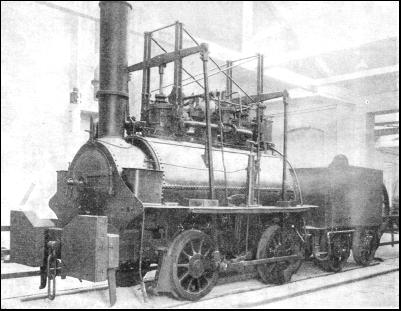

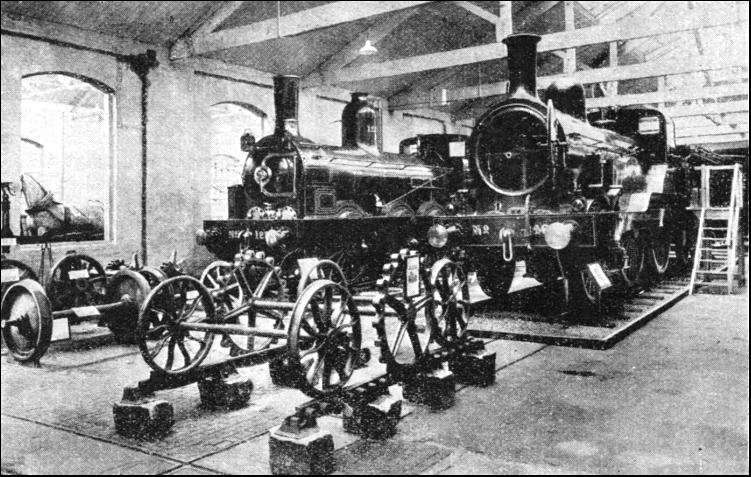

Edge rails for flanged wheels were first introduced in 1789 as an alternative to the tram-roads. It was the edge type of rail that was adopted for the first public railway worked by steam engines (the Stockton and Darlington line, constructed under the supervision of George Stephenson, and opened in September, 1825). The rails of this pioneer public railway were of wrought iron. In the York Museum there are to be seen some of the rails used on the original Stockton and Darlington system. As a matter of history, it was only during the construction of this line that George Stephenson decided that wrought iron rails were better than cast iron, a decision that caused him much personal loss, since he was interested financially in the manufacture of the short, bow-shaped cast-iron rail. The rails laid down for the original Stockton and Darlington Railway, such as we see in the York Museum, were from 12 to 15 ft. long, and weighed 28 lb. to the yard. A case of rail sections in the museum illustrates the growth in the size of rails from 1830 onwards, the smallest rail in this exhibit being that used on the Leeds and Selby Railway, weighing 36 lb. to the yard. Contrasting with this exhibit, there is a photograph of the well-known crossing of manganese steel at Newcastle-on-Tyne, one of the largest railway crossings in the world. Undoubtedly the most attractive exhibits in the York .Museum are the many historic locomotives, dating from the infancy of railways, and the numerous photographs and diagrams of noteworthy engines. One of the very early locomotives was that made by Matthew Murray for Blenkinsop, of Leeds, in 1811 or 1812. Unfortunately, the original engine has disappeared, but in the museum there is an interesting contemporary print of the machine. The Blenkinsop locomotive was of the rack-and-pinion type, and it ran for many years on the Middleton Colliery Railway, near Leeds. Another interesting print in the museum shows the Hedley engine of 1813, the first smooth-wheeled adhesion locomotive, which may be regarded as the true progenitor of the locomotive of to-day. George Stephenson's first locomotive was made in 1814. It was an adhesion locomotive, with two cylinders, and is said to have drawn eight loaded carriages, or 30 tons, on a slightly rising gradient, at four miles an hour. This was, of course, a big advance on any previous locomotive. So successful did it prove that George Stephenson was called upon to provide locomotives for various collieries, and early in the eighteen-twenties he had engines running not only at Killingworth, but also at Hetton. The pride of the York Railway Museum is the original "Hetton" locomotive of George Stephenson and Nicholas Wood, built at the Hetton Colliery workshops in 1822. It was rebuilt in 1857, and again in 1882, when the present link motion was fitted.

It is not quite clear for how long the engine worked, but, according to some authorities, it was in harness until 1913. Under its own steam, the "Hetton" led the Railway Centenary procession of old and modern locomotives at Darlington, on July 2, 1925. Before we come to the other locomotive exhibits in the York Museum, our attention is directed to an interesting display consisting of the lathe wheel and the tools used by George Stephenson in making his early engines. Among these tools is a number of "taps" used in threading holes for screws, these being the same in principle as the tools employed to-day. Another exhibit is George Stephenson's report on the Stockton and Darlington Railway, dated January, 1822. This is the original report, written in a school exercise book. The first survey was made in 1818 by a Welsh engineer named Overton. The original Parliamentary Bill for the Stockton and Darlington Railway was defeated, and it was only after the Bill for the railway was passed, in 1821, that George Stephenson was asked to undertake a new survey. It appears that the line was intended to be worked by horses, and Stephenson was engaged, not as a mechanical engineer, but as a civil engineer. Now we come to prints of two other early locomotives—the "Royal George" and the "John." The "Royal George" was built by Timothy Hackworth at the Stockton and Darlington Company's Shildon Works in 1827. The descendants of Timothy Hackworth claim that many improvements embodied in this engine were the inventions of its designer. Among the most important additions were the spring safety valves, fitted by Hackworth in 1829. These are preserved in the museum, and are all that is left of the "Royal George." The engine "John" ran on the Blyth and Tyne Railway, which was essentially a colliery line ; the print bears the date 1832. Two ancient locomotives that now claim our attention are the "Derwent" and "Engine 1035." The "Derwent," which was preserved on the main platform at Darlington Station, is represented at York by a photograph. It was built in 1845 by Alfred Kitching, and is a six-coupled mineral engine, of a type much used by the Stockton and Darlington system. In working order it weighed twenty-two tons. "Engine 1035," on show in the museum, was built at Shildon in 1874. It has a comparatively long boiler. The original number of this locomotive was "35," and, when the Stockton and Darlington became merged in the North Eastern system, one thousand was added to the numbers of the Stockton and Darlington engines, to avoid duplication of numbers. A similar method was adopted after the amalgamation (in 1923) of the various companies forming the London and North Eastern Railway, in re-numbering carriages, wagons, and other rolling-stock.

Next to the "Hetton" engine in popularity comes the first of Patrick Stirling's famous "8-footers" of the Great Northern Railway. This locomotive was driven into the museum under its own steam. It has a single driving wheel of 8 ft. 2 in. diameter, and weighs with tender about seventy-eight tons. The "Stirling No. 1" took a prominent part in the Railway Races of 1888 and 1895, and created a great sensation at the time of its introduction. Another interesting exhibit is "Engine No. 1275," built in 1874. This was known as a "Quaker" engine, because it was designed by William Bouch, a former engineer of the Stockton and Darlington line, which was nicknamed the "Quaker Railway." It is a mineral engine, built by Dübs and Co., of Glasgow, and has a very long boiler. Another interesting locomotive on show is "No. 910," built in 1875 for main-line express passenger work, to the design of Edward Fletcher. It was fitted for testing purposes with an early form of the vacuum brake. Continuing our stroll through the museum, we next come to the engine "Gladstone," in its gay coat of daffodil yellow. This engine was built for the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway in 1882, to the design of William Stroudley, and has many features of special interest, including an arrangement whereby the flanges of the leading wheels are lubricated with a spray of water. When this engine was designed, it was considered rather a novelty to have two wheels of large diameter as leading wheels, and the lubrication was presumably intended to help in the negotiation of curves. Modern locomotives are represented in York Museum by many interesting photographs and diagrams. There are, for example, the L.N.E.R. "Pacific" engine, "Enterprise," weighing with its tender, 159 tons, as compared with the six and a half tons of "Locomotion No. 1" ; the "Garratt" type locomotive weighing 176 tons, employed largely for coal train haulage ; and the "Mikado" class of machine, fitted with booster, weighing with tender just over 151 tons, and specially adapted for hauling heavy trains of 100 loaded brick wagons between Peterborough and London. These exhibits are an instructive contrast to the old engines of Stephenson's day. Leaving the locomotive exhibits behind, we pause to inspect the first iron bridge ever built, two of the three original spans of which are on show at York. The Stockton and Darlington Railway did not end at Darlington. but farther west, its purpose being to convey coals from the West Durham pits to the port of Stockton-on-Tees. Locomotives worked the coal wagons from Shildon (west of Darlington) to Stockton. but on the hilly portion west of Shildon steam engines and ropes were employed on the inclines, and the level portion was worked by horse haulage. The bridge shown at York carried this horse-worked portion of the railway across the River Gaunless. It was built in 1825 by John and Isaac Burrell, of Orchard Street, Newcastle-on-Tvne, to the design of George Stephenson, and dismantled in 1900.

Another interesting exhibit takes the form of a "dandy cart," to which is attached a life-size model of a horse. When the train came to a down gradient the horse was detached and stood aside. After the train had passed, the horse jumped on to the "dandy cart" and secured a ride downhill. George Stephenson was the inventor of the "dandy cart," and the first vehicle of this kind appeared about 1828. Travelling in the early days of railways was something of an ordeal for the third-class passengers. Many of the third-class coaches had no roofs. One of these open coaches has been lent by the Southern Railway to the museum. It formerly ran on the Bodmin and Wadebridge Railway, in Cornwall (1834-1886). The buffers are of solid wood. First-class carriages had buffers stuffed with horsehair. Another interesting exhibit is a Stockton and Darlington Railway composite carriage of the eighteen-forties, which probably survived until about 1870, as the four axle-boxes carry the dates 1844, 1846, 1867 and 1869 respectively. In those days wheels-often broke and had to be replaced, and the task of the wheel-tapper was doubtless more exacting than it is to-day. At the end of the carriage may be seen a seat on which the guard sat aloft, and the notched hand-brake which he used. Luggage was conveyed on the roofs of carriages, and special luggage slides were provided. The first-class portion is comparatively luxurious. From Bootham Junction, York, there has been brought into the museum the body of a third-class carriage used on the York and North Midland Railway, but in later years serving as a platelayers' cabin. This carriage is little more than a rectangular box with doors. No windows are provided except small panes in the doors. The compartments are divided by half-partitions serving as backs for the hard wooden seats. A single oil lamp dimly illuminated the interior. Contrasting with these old carriage exhibits are photographs of modern passenger rolling-stock, including dining-cars, first- and third-class sleeping-cars, and Pullman cars. Of the immense number of miscellaneous exhibits in the York Museum, space will permit of reference to only a number of the more important items. Signalling progress is revealed in many attractive displays. Outstanding among these is the only remaining specimen of a signal lamp with coloured slides, as used on the Stockton and Darlington line about 1840. The electric telegraph was first adopted for railway working between Paddington and West Drayton, on the Great Western Railway, in 1838, and in the York Museum there are several exhibits of early telegraph instruments, telegraph forms, and other equipment. Another fine exhibit consists of the block working signalling apparatus used for the operation of the Shildon Tunnel, between the years 1854-1868. In the museum the instrument is properly wired up, and it works very slowly, the messages being conveyed by means of a code, the key to which is printed on a dial. As illustrating how great a curiosity the instrument was at the time of its installation, a code is provided ("VIVI") for the words : "I am showing the instrument to a friend" ! Evidently this was a popular plaything among railway enthusiasts of former days. A fine collection of single-line staffs makes a splendid exhibit ; while a miniature "chamber of horrors" is provided in a number of railway police exhibits, including jemmies and revolvers, counterfeit coin and flash "Bank of Engraving" notes which card-sharpers and confidence men, caught "on the job" by the railway police, have handed over.

The Briggs' Collection, to which reference has been made, consists mainly of books, prints and manuscripts relating to the engineering side of railways. It is housed in a separate section of the York Museum, and includes many valuable documents bearing the signatures of George Stephenson, Robert Stephenson, Isambard Brunel, George Hudson, and other railway giants of the past. One leaves this treasure-house of railway relics with regret. Almost every month new exhibits are being added, and all who are interested in the history of our railways should make a point of visiting the museum. There is no charge for admission. The York Museum presents opportunities for the study of railway matters which are almost unequalled in Britain. The wonderful working models at the Science Museum at South Kensington, London, have, of course, given pleasure and instruction to thousands of visitors, but at York there is accommodation for a large number of prototypes. The full-size engine creates a lasting impression, and the excellent workmanship of the veteran locomotives on show at York always calls for the unqualified admiration, of all railway enthusiasts.

Many thanks for your help

|

Share this page on Facebook - Share  [email protected] |