|

|

BEFORE the royal train used by the King and the Queen begins its journey there are many arrangements to be made , the time-table has to be worked out with its consequent effect on other trains, and the necessary instructions issued to all concerned. When particulars have been received stating the exact number of persons who are to travel, the marshalling of the train is decided on. A diagram is made out showing what vehicles are to be used and which is to be the leading end of each vehicle. On this diagram is the length over buffers of each vehicle, the total length of the train and the distance from the front of the train to the King's doorway. This last information shows the locomotive department where the engine is to stop, and the engineering department where to lay the red carpet. The weight of each individual coach and the total weight of the train have to be shown so that suitable engines for the load can be selected. The diagram depicts the passengers and the seats they are to occupy. When the diagram is finally approved a copy of it is sent to Buckingham Palace. One particular royal train is historic. During certain periods of the Great War it was the travelling workshop and home of the King and the Queen. In some quiet branch station where it stopped for the night in those days of alarm, the royal party rested. The sentiments of the King and the Queen towards it are well known. Some years ago it was proposed to paint the train in the livery of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway, but at the request of the King the old chocolate and white was retained. In addition to paying first-class fares for every member of the royal party and suite, the King pays 13s. 4d. per mile for the use of the royal train. In the summer the usual procedure is for the King to use the Southern Railway royal train on his visit to Portsmouth, before embarking in the royal yacht for Cowes. After Cowes Week the King and the Queen return to London and go on to Sandringham, using the London and North Eastern royal train. For the journey to Ballater, the station for Balmoral Castle, the L.M.S. royal train is used, although it is hauled over L.N.E.R. metals from Wolferton, the station for Sandringham, by L.N.E.R. locomotives. The honour of being entrusted with the driving of the royal train is not the prerogative of any one man, but is spread over a number of veteran drivers.

The cost of the return journey from London to Ballater has been estimated as £450 each way. When Sir William Harcourt was Home Secretary in the 'eighties he told a friend that Queen Victoria spent no less than £5,000 on a return journey from London to Balmoral. Look-out men had to be stationed at every 200 yards along the line, and allowing for eight men to the mile, about 4,500 additional men were required, which added considerably to the cost. Queen Victoria spent £10,000 a year on railway travel. Traffic arrangements for the safety of the royal train are comprehensive. Before the train is due all level crossing gates are locked ; half an hour before the train enters a siding all shunting is stopped, and goods trains in sidings examined to ensure that nothing has shifted and everything is clear. The royal train is signalled mile by mile, by lamp or flag, according to the hour, for the whole journey. Four sharp rings, repeated three times, is the signal-box announcement that the train is approaching. The call signal, "RX," of the telephone operators and telegraphist on the train takes priority over all other communications. With the exception of one year, the Court has always made the journey to and from Scotland by train. In 1910, however, the King and the Queen decided to return to London by road, as a railway strike had occurred, and the King did not wish to embarrass the railway traffic staff.

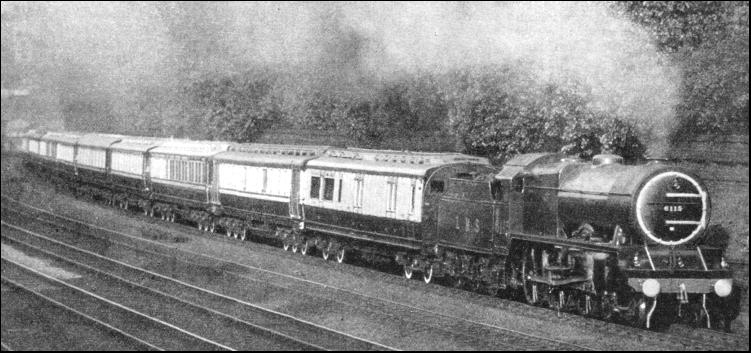

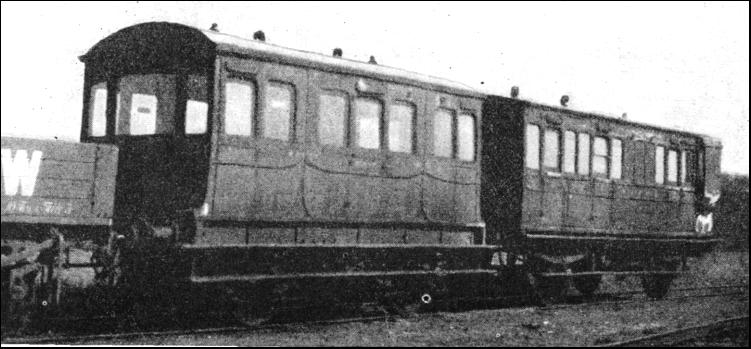

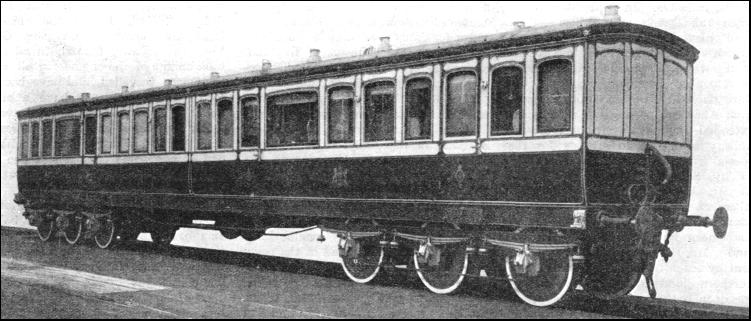

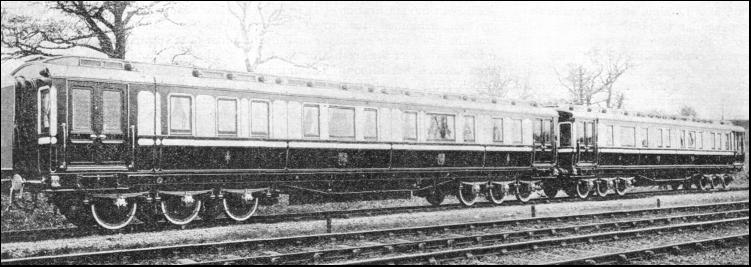

The royal train used by the King and the Queen on their annual visit to Balmoral Castle and when they wish to make a journey involving night travel is the property of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway. Although other companies have royal trains, this one is the best known. The vehicles are kept at Wolverton, and number about twenty, the number used varying according to the particular journey. The two royal saloons, which are furnished and decorated in accordance with the wishes of the King and the Queen, have not only carried the royal passengers for many thousands of miles, but have also served during the war of 1914-18 as a temporary home when the King and the Queen visited naval and military bases and munition centres. The two saloons were built for the use of King Edward and Queen Alexandra, as Queen Victoria's saloon had become obsolete. All the vehicles are painted in the old London and North Western colours, chocolate lower and cream upper panels, with the fine lining in gold leaf. The royal train generally consists of about ten vehicles. It is approximately 630 ft. long, excluding the engine and tender, and weighs about 370 tons. Next to the engine is a corridor brake coach with two first-class compartments ; the brake compartments are specially fitted with lockers containing tools and spare parts to replace any breakages that might occur during the journey. Telegraph and telephone instruments are carried. These can be connected with the telegraph wires alongside the track, so that communication may be established, if necessary, with the nearest signal-box or with central control. Two telegraphists always travel on the train. About six members of the carriage and wagon department staff act as train attendants,

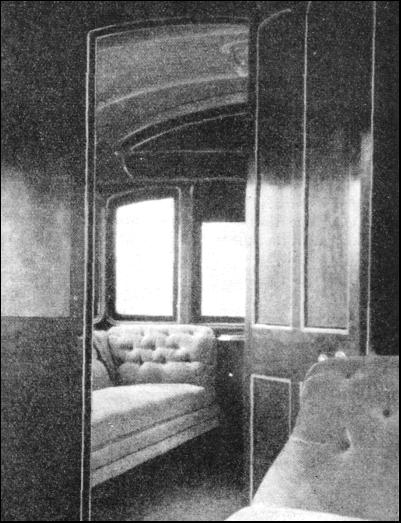

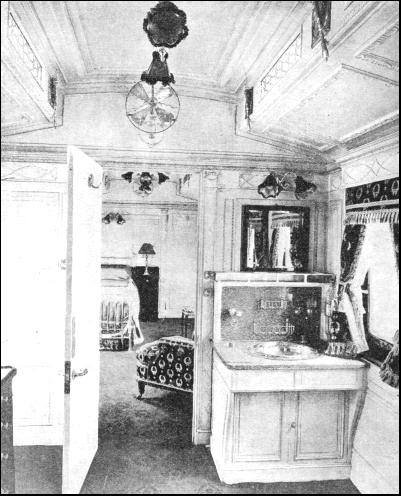

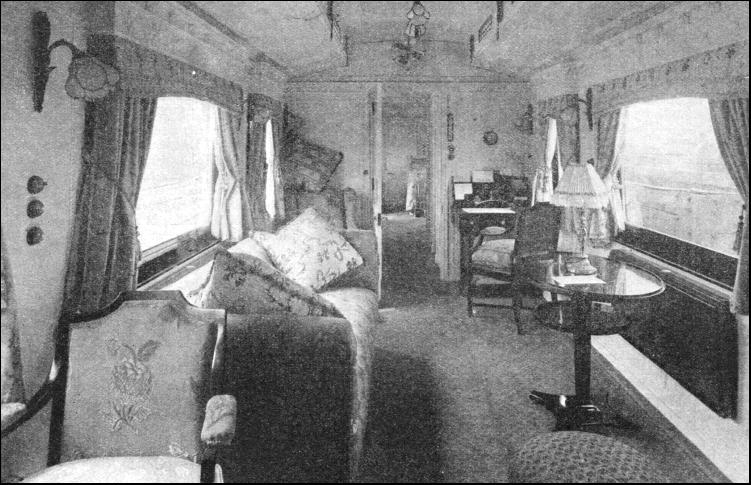

The first vehicle on the train is the mess-room for the train staff. The seats in the two first-class compartments are arranged to serve at night as beds on the Pullman principle, and each compartment will sleep four persons. As a rule these berths are occupied by servants of the royal household. The second coach is generally a sleeping-saloon for the lady-in-waiting and her maid. If the train is making a short journey by day, the second vehicle is a 57 ft. semi-royal saloon, in which the lady-in-waiting and lady passengers travel. If the train is a short one, the King's saloon is the second vehicle. The exteriors of the two royal saloons are different from the rest of the train. The colours are the same, but the cornice moulding is carved with an oak leaf design and gilded. The head-stock ends are carved with lions' heads, gilded. The door-handles and long commode-handles are gold-plated ; both are hand-chased, the door-handles with a crown design and the commode-handles with a lion's mask design. On the lower panels, in place of the L.M.S. coat-of-arms, there are the royal coat-of-arms and the arms of the various orders of chivalry—St. George, the Garter, St. Andrew, St. Patrick and the like—each being hand-painted. In place of the ordinary step-boards there are leather-covered folding steps reaching to the ground, relics of the days of the horse-drawn State coaches and similar to the steps of the open horse-drawn landau still used by the King and the Queen on State occasions. The King enters the saloon by two large polished teak double doors, opening on to a square vestibule. Leading out of this vestibule is the King's smoking-room, which is finished in "fiddle-back" mahogany, so named because the wavy marking of the wood is similar to that often seen on violins. In either corner of the smoking-room is an armchair covered in apple-green morocco leather, and on cither side a table in "fiddle-back" mahogany to match the walls. This is the room which the King and the Queen generally occupy in the daytime. The Queen has her own saloon, but only the King's saloon is used on short journeys, unless the Queen has to change her costume during the journey.

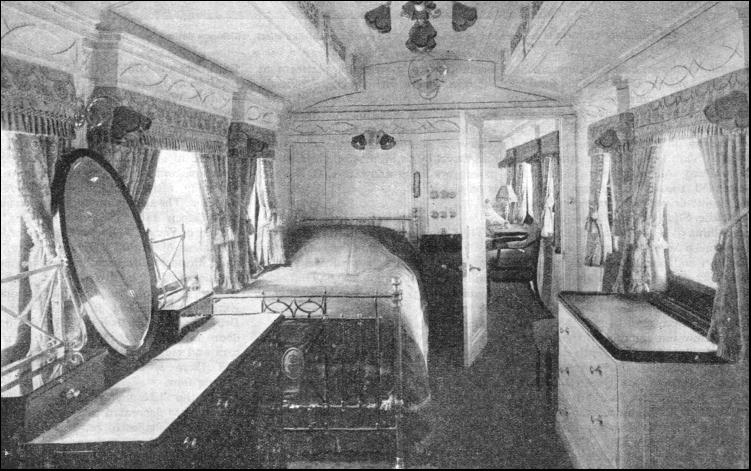

The day compartment is next to the smoking-room. Some of the furniture is trimmed with green silk rep ; the rest of the furniture is trimmed in a copy of Jacobean tapestry with quaint figures on a creamy ground. In the King's day compartment is a couch with a history. King Edward fell downstairs and broke an ankle ; the ankle remained weak for some time, and in order to provide adequate rest while the King was travelling, the couch, with a drop end, was made and placed in the royal saloon. There is a desk in this compartment to enable the King to conduct affairs of State while travelling. Urgent documents are brought to the King by a king's messenger at any station where the royal train stops. Leading from the day compartment is the King's bedroom, with a silver-plated bed, satin-wood dressing-table and furniture. The next compartment is the bathroom, with a marble wash-basin. This was formerly a dressing-room, but the bath was installed during the last war, when their Majesties lived on the train for as long as a week at a time. Beyond the bathroom is the last compartment in the King's saloon, which is reserved for the sergeant footman who attends the King. The "master" switches for the electric lighting, heating and fans are in this compartment, which is furnished with an arm-chair-bed convertible seat. The vestibule and the sergeant footman's compartment are heated by steam, but the rest of the saloon is heated electrically from a fifty-volt train lighting set carried in the rear brake-van. Even in cold weather the King likes very little heat in his saloon. He prefers to keep the saloon cool, and to get warmth from a travelling rug thrown over his knees. In hot weather the temperature is kept at sixty degrees by means of ice in silver bowls, and by the use of electric fans. The Queen's saloon is similar in outside appearance to that used by the King but has a different interior plan. The colour scheme is in blue. The entrance vestibule is the same as the entrance to the King's saloon, and the two saloons are gangwayed together so as to have the two vestibules adjoining.

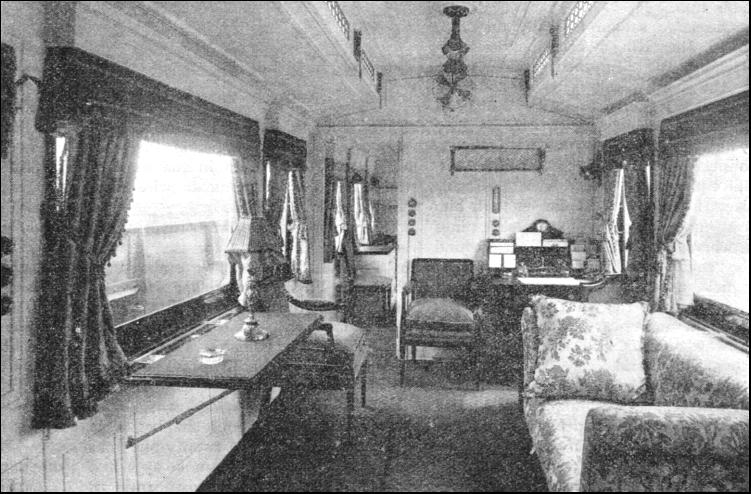

The vestibule leads into the Queen's day apartment, which has two writing desks. Everything is balanced in pairs. The reason for this "balancing" is that the saloon was originally designed for Queen Alexandra, who was always accompanied by Princess Victoria. The chairs at the writing-tables are stuffed with a very fine eiderdown. The woodwork of the furniture is of satinwood. The walls of the two royal saloons, except the King's smoking-room, are finished in white enamel, the decoration being Georgian in character. This white enamel gives a yacht-like effect, which was desired by King Edward. Adjoining the Queen's day apartment are the dresser's apartment and the Queen's bedroom. Formerly there was one large bedroom with a bed at either end, one for Queen Alexandra and one for Princess Victoria. The present Queen had the bedroom partitioned off to form a smaller bedroom for her maid, or dresser, as she is styled. The furniture is covered in blue silk brocade with a design of pagodas and little Chinese figures sprinkled over it. The Queen's bathroom, which adjoins, has a rose-pink marble washstand and a bath similar to that used by the King, both having been installed at the same time. Beyond the bathroom is the compartment of the Queen's footman, which is a replica of that of the sergeant footman. There is in these compartments a private telephone connecting the sergeant footman, the Queen's footman, the King's valet and the front brake van of the train.

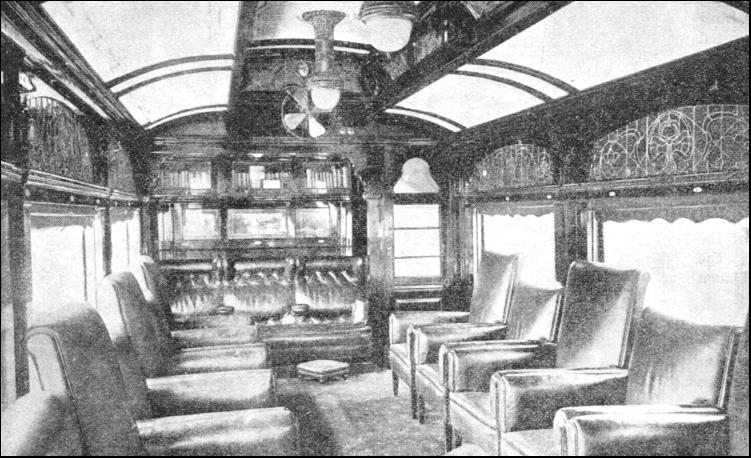

The royal dining-car is behind the royal saloon, with the kitchen end at the rear. This car, of the standard type, is finished in marquetrie. It was built in 1900, and is one which was exhibited at the Paris Exhibition of that year, when it gained a grand prix. The upholstery differs from that of standard dining-cars, as it is in blue and brown tapestry. The King and the Queen, members of the Royal Family and the royal suite dine in this car. The King sits with his back to the engine, the Queen facing the engine. The food is cooked and served by members of the L.M.S. hotels department, and the menu is always shown to the Queen for her approval. The saloon for the royal suite is next to the dining-car, and accommodates the equerries and other officers. It is 57 ft. long and is one of six built at the same time as the two royal saloons. It is of similar profile to the royal saloons and the inside is finished in white enamel, although the interior decoration is plainer. At the end of this saloon is a compartment for the attendants. It is a large room, about 17 ft. long and 9 ft. wide, in the centre of the coach, with a smaller room opening out of either end. This large room has folding doors fitted across the centre, so that it can, it desired, be made into two rooms. Bedsteads can be provided, and this allows of two small rooms being turned into bedrooms with the large room between as a sitting-room, or by using the folding doors four bedrooms can be made up. The large saloon is really an office where the King's correspondence is attended to. In each compartment of the King's saloon is a bell-push marked "Equerry." Every vehicle of the train in which the equerry on duty is likely to travel is fitted with sockets connected by wires to these bell-pushes. The equerry is provided with a portable electric bell, which he carries with him if he moves about the train and plugs in wherever he may be sitting. Behind the royal suite saloon is a similar vehicle used by the railway officials accompanying the train. Farther back still is a dining-car for the use of the railway officials and members of the Royal Household. The last vehicle of the royal train is another brake van similar to the leading one. It contains the electrical equipment for heating the royal saloons, and also the bedding and the royal luggage. The guard who is accompanying the train travels in this vehicle. As it is not convenient for the train staff to travel through the royal saloons, telephones are fitted throughout the train so that the train staff in the front of the train can communicate with their colleagues at the back. The Southern Railway royal train, which the King uses for the journey to Portsmouth, where he embarks in the Royal Yacht, "Victoria and Albert," for his holiday during Cowes Week, has associations with the Royal Navy, and has carried the King on a number of occasions when he has reviewed the Fleet.

When H, M. S. "Victory" was afloat in Portsmouth Harbour she began to fire her royal salute of twenty-one guns directly the first puff of smoke appeared from the engine of the royal train as it departed for London with the King, and the sight of Nelson's flagship banging away her guns as the train drew out of the station—the old saluting the new—was magnificent. The Southern Railway's royal train generally consists of the following vehicles, after the engine : 1. Saloon brake. 2. First-class corridor. 3 and 4. Saloon coaches. 5. Royal saloon. 6. Saloon brake. The royal saloon was built in 1903. All the vehicles, including a saloon coach which is in reserve, are kept at Purley, completely covered by sheets that envelope the coaches. The royal saloon, the upholstery of which is in apple-green, is a beautiful apartment, and it is difficult to realize, such is the care bestowed upon it, that it was not made yesterday. Almost every head of a foreign State visiting England lands at Dover and travels over the Southern line to Victoria. Pullman coaches are used for their conveyance. Distinguished foreign visitors from countries troubled by political disturbances have to be carefully protected. Sometimes tact is needed, as on the occasion when the former Shah of Persia summoned the railway officials before him and demanded the instant decapitation of the engine-driver for having exceeded what the Shah regarded as the safe speed limit of ten miles an hour. In Queen Victoria's days the London Brighton and South Coast Railway, in the effort to be immaculate, used to whitewash the whole of the coals on the top layer on the tender of the engine of the royal train, and to put the Royal Arms below the chimney of the engine. Royal saloons are frequently attached to ordinary trains. During the holiday of the King and the Queen at Eastbourne in 1935, the Southern Railway royal saloon, for instance, was attached to an ordinary train when the Queen wished to visit London. When foreign visitors of importance arrive in England the saloon is attached at Dover to the boat express but is detached at Herne Hill Station and drawn by another locomotive to a reserved platform at Victoria, where British State officials, reporters and photographers and news-reel men are waiting in readiness. Members of the Royal Family often reserve a compartment in an express and travel by train, most of their fellow-passengers being unaware that Royalty is on the train.

The Great Western Railway provided the "Honeymoon Train" which carried the Duke and Duchess of Kent from Paddington to Birmingham on Thursday, November, 29, 1934. The formation of the train was : Locomotive No. 6,000, "King George V" : Seventy-foot first-class brake coach : Seventy-foot first-class corridor coach : "King George V" special coupé saloon : Seventy-foot first-class brake coach. The "Honeymoon Train" left Paddington at 4.20 p.m. and arrived at Snow Hill Station, Birmingham, at 6.20 p.m., drawn by the first of the "Kings," for the engine was the one exhibited in the United States at the time of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Centenary Exhibition in 1927. It was built at Swindon Works, is 68 ft. 2 in. long over the buffers, and weighs, with the tender, 135 tons 14 cwt. The coupé saloon, "King George V," was one of eight designed and built at Swindon, and named, by permission of the King, after members of the Royal Family. The names of the other seven are "Queen Mary," "Prince of Wales," "Duke of York," "Duke of Gloucester," "Duchess of York," "Princess Mary," and "Princess Elizabeth." These saloons arc 60 ft. long and 9 ft. 7 in. wide, as are those of the Cornish Riviera Express—the widest in use in Great Britain. Each car is divided by sliding doors into two sections, seating seventeen and eight passengers respectively, and there is a coupé compartment seating four. For the "Honeymoon Train" the interior was decorated in autumn tints, the various shades of brown giving an atmosphere of warmth and comfort. The chairs, of the wing type with loose cushions, were upholstered in brown-patterned moquette, and the floor was covered with brown carpets. The saloon was panelled in highly polished natural light walnut veneer, with dark burr walnut pilasters on panels between the deep windows. The ceilings were panelled in flat stippled vellum, and the saloon was lighted by concealed electric lights covered by satin-faced gloss panels in bronze frames fitted flush with the ceiling and end panels of the saloon. Queen Victoria insisted on a speed limit of forty miles an hour, but when King Edward came to the throne the Great Western were able to show what they could do. The first non-stop run between Plymouth and London was made on March 10, 1902, by the train bringing King Edward and Queen Alexandra to London. A few days before the train had left Paddington at 10.30 a.m. and travelled non-stop to Kingswear (228-1/2 miles) in four hours twenty-five minutes, the occasion being the laying of the foundation stone of the Royal Naval College, at Dartmouth. The royal party went on to Plymouth. On March 10 the train left Millbay Docks Junction, Plymouth, at 11.40 a.m. and reached Paddington, 246-1/2 miles, at 4.24 p.m., without having stopped.

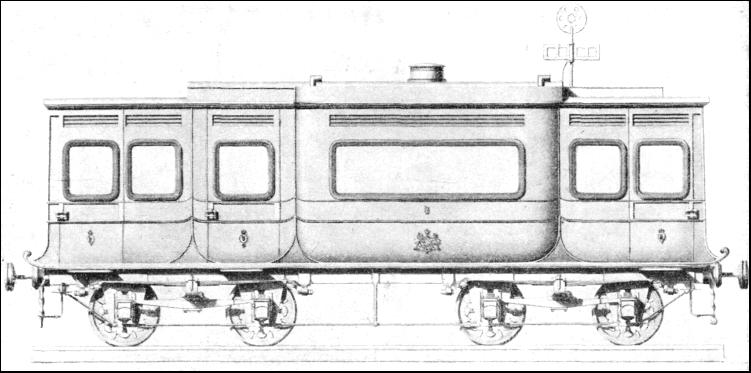

Both journeys were made to schedule without any attempt at specially fast running. This was before the opening of the Westbury "cut-off," and the route was twenty miles longer than the present one. Water troughs had just been laid at Creech, near Taunton. The load was 127 tons, and the engine, on both runs, was "Baden Powell," renamed "Britannia" for the occasion, a 4-4-0 of the "Atbara" class with 6 ft. 8 in. coupled wheels. This speed was, however, exceeded by the train that carried the then Prince and Princess of Wales, the present King and Queen, from Paddington to Plymouth on July 14, 1903, when the time for the run was cut to three hours fifty-four minutes, or thirty-six minutes ahead of schedule. Speeds of more than eighty miles an hour were attained on the run to Bristol, which city was reached in less than one hour and three-quarters. The first royal saloon was built by the Great Western. It was ready in July, 1840, a newspaper account of the vehicle being : "The Great Western Railway Company, anticipating the Patronage of the Queen and her illustrious Consort, Prince Albert, and ot the Members of the Royal Family, have just had built a splendid royal carriage for their accommodation. It is a very handsome vehicle, 21 ft. in length and divided into three compartments, the two end ones being 4 ft. 6 in. long and 9 ft. wide, while the centre forms a noble saloon, 12 ft. long, 9 ft. wide, and 6 ft. 6 in. high. The exterior is painted of the same brown colour as the others of the Company's carriages, and at each end is a large window affording a view of the whole of the line. The interior has been most magnificently fitted up by Mr. Webb. The saloon is handsomely arranged with hanging sofas of carved wood in the rich style of Louis XIV, and tlie walls are panelled out in the same elegant manner, and fitted up with rich crimson and white silk and exquisitely executed paintings representing the four elements by Paris. The end compartments are fitted up in the same style, each apartment having in the centre a useful and ornamental rosewood table; the floor of the whole is covered with India matting." The carriage was built by David Davies, of London, and appears to have been similar to posting carriages with the body inside the wheels. In its original condition it was probably used only by Queen Adelaide and Prince Albert, as a minute of the general traffic committee records that the Queen's carriage was likely to be required for a journey by the King of Prussia, and that it needed improvements, being less easy and not so safe on four wheels as the first-class carriages. Brunel recommended a new frame on eight wheels, and the alteration was carried out, apparently, before Queen Victoria made her first journey in it, on June 13, 1842. It was altered in 1851 to an ordinary saloon, and was broken up in 1879.

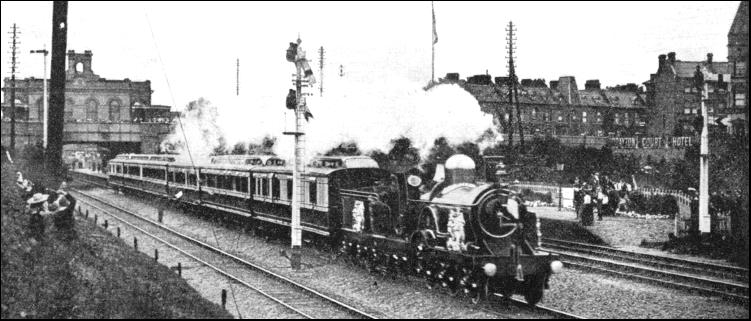

Queen Victoria was not the first royal person nor the first queen to travel by train in England. On November 14, 1839, Prince Albert, then the Queen's suitor, accompanied by his elder brother, took the train from Slough to Paddington, after he had visited the Queen at Windsor Castle. After his marriage in the following year he travelled frequently by train. The first "Queen's carriage" was used on August 15, 1840, by the Dowager Queen Adelaide (widow of William IV), from Wallington Road to Slough. The King of Prussia, who had arrived at Windsor for the christening of the Prince of Wales, travelled to London from Slough by the railway on January 24, 1842. Queen Victoria decided to make the journey by rail, and the company was notified of her decision. Before noon on June 13, 1842, the royal train was waiting in Slough Station. The Queen arrived, examined the royal saloon and the line, made searching inquiries into the whole of the arrangements, and then entered her saloon. The famous Gooch, the superintendent of the locomotive department, and the still more famous Brunel, were responsible for the engine, although it is doubtful if Brunel drove it ; more probably Gooch did. Precisely at noon the train started. More than an hour before, Paddington was the scene of a great animation. A crimson carpet was laid from one end of tlie platform to the other. Elegantly dressed ladies (wives, daughters and friends of the directors) were agog with excitement. A detachment of the 8th Royal Hussars arrived. At twenty-five minutes past noon "Phlegethon". hauled the royal train into Paddington. The Queen was so pleased that on July 23, when she returned to Slough (for Windsor) with Prince Albert, she had with her the Princess Royal, and also the eight-months'-old Prince of Wales. But she never liked speed. The Hon. Alexander Gordon wrote from Osborne, in 1850 : "I am desired to intimate Her Majesty's wish that the speed of the Royal Train should on no account be increased at any one part of the line in order to make up for the time lost by an unforeseen delay at another, so that if any unexpected delay does take place, no attempt is to be made to regain the time by travelling faster than what has been agreed upon in the Time-bill you have sent me. This order has probably arisen from one of the Directors telling Her Majesty last year that they had been driving the train at tlie rate of sixty miles an hour, a gratuitous piece of information which, very naturally, alarmed Her Majesty, although it was probably incorrect. I have to request you will communicate Her Majesty's wishes to the secretaries of the other Railways concerned." The second G.W.R. royal saloon, built in 1848, had a disk-and-crossbar signal fitted on tlie roof to enable the Queen's attendants to convey her desires as to speed or stoppage to the look-out men in the "iron coffin" on the tender, and so to the officer in charge of the engine. This carriage was altered to the narrow gauge in 1889, and was broken up in 1903. The wood body was made by Davies, of London, and the iron frame at Swindon. This idea of a special signal was used on other royal saloons. One in use on the London and North Western Railway comprised a dial and lever, by which the signal to go slow or to stop could be given by the officer in the saloon. The look-out man on the tender had not only to watch this signal, but was also required by the regulations to be responsible for watching both sides of the train for signals. In 1855, when Queen Victoria was travelling from King's Cross to Edinburgh, on the Great Northern Railway, a van was found to have heated in running. At Grantham a man was "placed on the footboards to grease the vehicle while running." At Darlington the man was killed, and the royal saloon had to be shunted off.

In 1855, when the Queen and Prince Albert were returning from Scotland to London, the axles of one of the carriage trucks ran hot, and the vehicle was detached at Forfar ; farther south, at Kirkliston, one of the steam-pipes burst, and the train came to a standstill, causing an hour's delay. Meanwhile, alarm was caused at Edinburgh by the non-arrival of the train, and a pilot engine was sent in search of it. Queen Victoria's early journeys were excellent advertisements for the safety of the railways. In September, 1848, when the Queen and Prince Albert were aboard the Royal Yacht at Aberdeen, fog prevented the vessel from putting to sea, and it was decided to return to London by railway. In those days there was no through service from Aberdeen, nor was the telegraph extended sufficiently to enable the railway to use it to arrange for the special train. Soon after noon, on the Friday, September 29, word was sent to Mr. Errington, Engineer of the Aberdeen Railway, then in course of construction, who was in Aberdeen, that the Queen had decided to return by land. Mr. Ker, the assistant engineer, sent by coach to Montrose, the extreme northern point to which the railway was open to the south. From Montrose to Perth arrangements were made only half an hour before the Queen arrived, on a wet and foggy night. Owing to a blunder in single line working, there was a narrow escape of trouble between Forfar and Glamis, but the Queen was carried safely to London, and the "Railway Chronicle," of October 8, 1848, announced : "Between London and Aberdeen there were no fewer than six railways associated with the London and North Western. . . . When it is known that Her Majesty was conveyed over a distance of 500 miles, at the rate of 35 miles an hour, including stoppages, at a rate amounting to but not exceeding at any time fifty miles an hour over a country rising twice to an elevation of 1,000 ft. above the level of the sea, and descending at intermediate stations nearly to the level of the sea, and so conveyed without the slightest alarm or cause for danger, we may be permitted to say that the railways of England, under their present system of management, have reached an amount of perfection, regularity, and security unsurpassable and almost unhoped for." When Queen Victoria travelled to Scotland in 1850, all the London and North Western signalmen along the line were ordered to wear white gloves and salute the train as it passed, From the days of Fenian threats the lines were watched and patrolled with special care. A pilot engine was sent fifteen minutes ahead of the royal train, and no train was allowed to move until fifteen minutes after the royal train had passed All trains travelling in the opposite direction had to stop, and shunting was stopped over lines and sidings. Royal waiting-rooms were built at Windsor Station, and the beginning of a journey was almost a State occasion. Half an hour before the train was due to start, the pages, upper servants and maids arrived and occupied their seats, then came the ladies of the Royal Household, the equerries, and the Lords-in-Waiting, and, finally, the Queen. The royal saloon was opposite the door of the royal waiting-room. After the Queen had taken her seat the train was drawn forward, and then halted for two minutes for the rear part to be attached. It then began its journey. Mr. Daniel Gooch, afterwards created a baronet, was proud of his connexion with the royal train. He wrote in his diary : " While I had the office of locomotive-engineer on the Great Western Railway, I nearly in all cases took charge of the engine myself when the Queen travelled, and have been so fortunate as never to have a single delay with her, and she has travelled under my care a great many miles. I was the first who had such a charge, and it was some time before she had occasion to travel on any line but the Great Western." The Queen thought, too, of the efforts of the railway officers on her behalf. In 1892 she heard that Mr. G. P. Neele, the superintendent of the London and North Western Railway Company, had completed his hundredth journey in charge of the royal train. She presented him with an elegant, massive chiming clock bearing a suitable inscription on a tablet beneath the dial.

Many thanks for your help

|

Share this page on Facebook - Share  [email protected] |