|

|

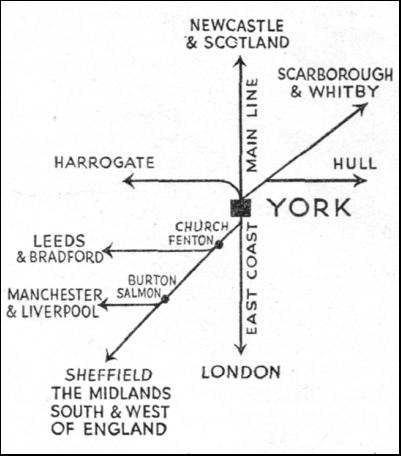

AT one time there were two railway stations in Great Britain which probably offered to the railway enthusiast a greater interest than any others. They were Carlisle and York. No other British stations could show so wide a diversity of "visitors" in a day's working. Into Carlisle there came the trains of seven companies—the London and North Western, Midland, Caledonian, North British, North Eastern, Glasgow and South Western, and Maryport and Carlisle Railway Companies. York, the hub of the North Eastern Railway system, offered hospitality to the Great Northern, Midland, Great Eastern, Great Central, and Lancashire and Yorkshire Companies' trains, so that the trains of six companies were to be seen. To-day this variety has been greatly diminished by the grouping of the railways which took place at the beginning of 1923. But the geographical interest remains, and Carlisle and York are still the poles of a magnet which draws railway traffic from all points of the compass, even though only London, Midland and Scottish and London and North Eastern locomotives are now seen in the respective stations. The coaching stock is, however, still diverse. At York it is natural that most of the coaches should bear the varnished teak livery of the L.N.E.R. But not all of them do. London, Midland and Scottish trains arrive from Liverpool and Manchester, and, also, by the old Midland main line, from Sheffield, Birmingham, and even from places as far affield as Bristol and Bournemouth.

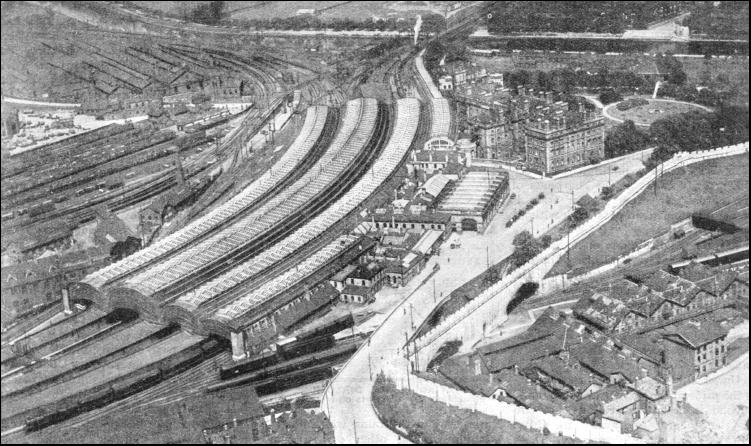

Twice a day in each direction, the chocolate and cream colours of the Great Western Railway are seen, one train working to and from Cardiff and Swansea, in South Wales, and the other to and from Oxford and Southampton. And once every day, going south at ten in the morning one day, and returning to York at half-past seven in the evening of the next, the Southern Railway makes its contribution with a through restaurant car train to and from Southampton and Bournemouth. Many of these "foreigners" work through to and from Newcastle-on-Tyne ; and it is thus possible for the traveller in search of variety to take breakfast, lunch, tea or dinner, as the case may be, in the cars of either the L.N.E.R., L.M.S.R., G.W.R., or S.R., at will, while travelling over the L.N.E.R. main line between York and Newcastle—a geographical phenomenon which no other line in England has to offer. The railway importance of York is due to its situation midway along the East Coast main line from London to Edinburgh, 188-1/4 miles from King's Cross and 204-1/2 miles from the Waverley Station in the Scottish capital. Before dining-cars came into existence, the big dining-room at York presented a very animated scene when the Anglo-Scottish express trains were in the station. Passengers were allowed twenty minutes in which to eat a hasty—very hasty—lunch or dinner, a haste which must have troubled not a few digestions. To-day, in the height of the season, the "Flying Scotsman" does not deign to stop at York ; lavishly equipped with restaurant car accommodation and every other amenity, it passes non-stop through the station on its journey of 392-3/4 miles from London to Edinburgh, but very slowly on account of the sharpness of the curve. No other regular train is so venturesome as to pass York without stopping. At no hour of the day or night is the great station at rest. During the day there are lulls in the frequency of the trains ; the traffic "peaks" are reached when trains converge from all directions to connect with the principal expresses between London and Scotland. Then the accommodation of the station is taxed to its utmost. Under the great curved roof, which is the pride of the station, and extending beyond it in both directions, are two of the longest platforms in Great Britain. The main down platform— No. 5—is 1,575 ft. in length ; No. 4, the up platform, which curves round to the Scarborough branch at the north end of the station, is even longer, being 1,701 ft. long. Between these two lengthy promenades are four tracks—two of them the platform roads, and two the central through lines used by non-stopping traffic, light engines, empty coaches, freight trains and so on. In the middle of the station are double cross-over roads connecting the through roads with the platform lines. These enable trains to run to or from either end of the main platforms, without interfering with trains which may be standing at the other end, so that—except for extremely long trains—each main platform can accommodate two trains at a time when necessary.

Outside the west wall of the station is another through platform—No. 14—which is used for either down or up trains. Between No. 14 and No. 5 there are two "bays," or short terminal platforms, at both ends of the station—four in all. On the east side there are similarly three bays at the south end, and four such platforms have been squeezed in at the north end. The total number of platforms at York, therefore, is three permitting through running—equivalent in value, as we have seen, to five—and eleven terminal, or fourteen in all. The first railway to reach York opened in 1830 and was the York and North Midland, which arrived from Normanton, where a junction was made with the North Midland line. To-day this line is used by the L.M.S. expresses from Liverpool and Manchester via Wakefield—the old Lancashire and Yorkshire route—into York. It is joined at Church Fenton, eleven miles away, by the L.N.E.R. line from Leeds, and the traffic is sufficiently dense to warrant four tracks from Church Fenton to York. In days gone by a couple of expresses were booked to leave York at 2.35 p.m., one for Liverpool hauled by a Lancashire and Yorkshire locomotive, and the other with a North Eastern engine at the head, for Leeds. Many a ding-dong race has taken place between the "Lanky" and the "Geordie" over this flat eleven-miles' stretch to Church Fenton ; although entirely unofficial, this daily "event" became quite famous. Unfortunately, the times of the two trains, which still run, have been altered, and the race was discontinued.

At Burton Salmon, seventeen miles south of York, the Normanton line is joined by another route of great importance. It is known as the Swinton and Knottinglcy joint line ; originally built jointly by the North Eastern and Midland Railways, it is now the property of the L.N.E. and L.M.S. Companies. It is the most direct link between York and both the L.N.E. and L.M.S. lines at Sheffield, so connecting north-eastern England with Nottingham, Leicester, Derby, Birmingham and Bristol. Every day through coaches are run from York, on different trains, to Southampton and Bournemouth, Newport, Cardiff, and Swansea, and even Exeter, Plymouth and Penzance, all using the Swinton and Knottingley line. Two miles before reaching York, the four-tracked route from Church Fenton is joined by a line coming in with a fairly sharp curve from the south-east. Although it has the appearance of a branch, .and was built after the Church Fenton section, this is the most important of all the lines approaching York, for it is the London and North Eastern main line from King's Cross. The two routes join at Chaloner's Whin Junction. Between this junction and York are some excursion platforms at Holgate Bridge, which are pressed into service at the time of York Races, or on other occasions when traffic is exceptionally brisk. Immediately beyond this the main station comes into view. Before it is reached, some tracks branch to the left, leading to the great marshalling yards, and providing a "by-pass" which enables a large proportion of the freight traffic to miss the passenger station. Traffic here is controlled by the huge locomotive yard signal-box, which contains what is probably the longest mechanical locking-frame in existence, with 295 signal-levers in one row. To the right more sidings branch out, and these are of interest as they occupy the site of the original York Station, which was a terminus. Past and present still rub shoulders on this side of the station. These sidings pass, by means of the Gothic archways which can be seen in the aerial view of the station, underneath the ancient city wall which encircles York. One of the original buildings has been put to an appropriate use. It houses the York Railway Museum. Here the London and North Eastern Railway has concentrated a collection of early locomotives, all with some claim to fame, belonging to various British railways of bygone days. Many other relics are housed here, including a variety of documents and pictures dating back to the earliest railways. At the north end of the station the main line to Scotland bears sharply round to the west and travels thus for a mile before it curves back to the northwards at the point where it rejoins the freight lines already mentioned. This curve makes a difficult start for heavy express trains out of the platform at York, but once they are clear of Poppleton Junction, just over one and a half miles from the start, they have before them one of the finest "race tracks" in the country. Northwards across the Great Plain of York the line runs for forty-two and a half miles from Poppleton Junction to Darlington, for the most part dead straight, and almost without a gradient.

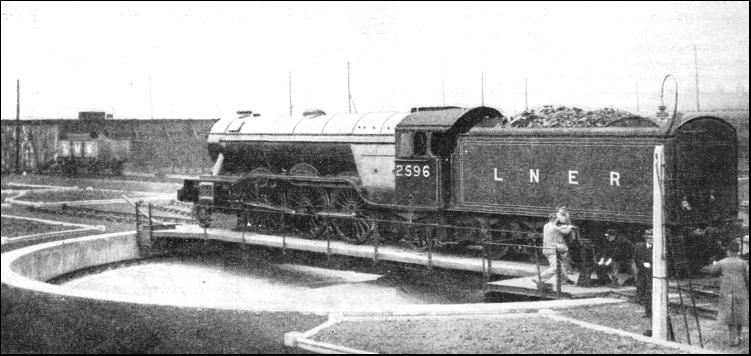

For many years the forty-three minutes' timing of the late North Eastern Railway from Darlington to York—a distance of 44.1 miles, entailing a start-to-stop speed of 61.7 m.p.h.—was the fastest in the British Empire ; it is still found in the time-table, but in the march of progress other and faster timings have been introduced elsewhere. A large proportion of the main line from York to Darlington is now four-tracked, and has been equipped with electrical light signalling, automatically operated except at junctions, so that the working over it of the dense traffic which passes between York and Newcastle has been greatly facilitated. Before the war the North Eastern Railway prepared plans for electrifying the York-Newcastle section, and even built a powerful express electric locomotive ; but the heavy cost prevented the fruition of the scheme. To the left of the sweeping curve out of the north end of York Station lie the locomotive sheds, which house a large number and variety of locomotives. Outside may be seen great "Pacifies," "Shire," and "Hunt" class 4-4-0's. "Great Northern Atlantics," and other earlier types still used on passenger service, together with 2-8-0, 4-6-0, 2-6-0 and 0-6-0 freight engines, different kinds of tank engines, and, very likely, one or two Sentinel-Cammell rail-cars. Along here every available space between tracks has been marked on with neat concrete edgings, and sown with grass plots, which are kept in perfect order, and give an impression of spick-and-span neatness not often associated with railway permanent way. Branching to the right, out of the north end of the station, there is the main line to Scarborough, which is used in summer by the "Scarborough Flyer." This train runs only during the height of the season, and then provides the fastest service of the day between London and York ; the run of 188.2 miles is made non-stop in 190 minutes both ways, entailing the high average speed of 59.2 miles an hour. An interesting feature of the Scarborough branch is that most of the intermediate stations have been closed, and the local traffic transferred to the roads. Consequently, the twenty-one miles from York to Malton, along this route, is the longest stretch of line in Great Britain without an intermediate station. At summer week-ends the Scarborough line is extremely busy. Special trains converge on York from all parts of the West Riding of Yorkshire, Lancashire and the Midlands, all making for Scarborough, and adding to the. complexities of York Station working. From the Scarborough branch diverges, by a line leading eastwards, the line to Beverley and Hull , and beyond Malton, to the north, the Pickering and Whitby branch. Also from the main line at Poppleton junction, which has already been mentioned, there travels in a westerly direction the branch leading to Knaresborough and Harrogate. Thus York is the focal point for important trains from a number of directions. The train-working at any busy period is a geographical study. Let us take one rush period of ninety minutes, from 8.55 to 10.25 in the morning. Just as the 8.55 a.m. "semi-fast" is leaving the north end of No. 5 platform for Newcastle, the business men's morning express service from Harrogate is arriving at one of the adjacent bay platforms. Four minutes later a "slow," headed by a 4-4-0 locomotive of the L.M.S.R., is arriving at the south end. At 9.05 a.m. another morning business train, from Scarborough to Leeds, swings round the curve from the Scarborough direction into No. 4 platform, and is just leaving, after hut two minutes' wait, when a local train of two coaches, from Pickering, steals from the north main line into the other unoccupied bay between Nos. 5 and 14 platforms. At 9.10 a.m. a rail-car leaves the north end of No. 5 for Harrogate. In the next few minutes trains arrive from all directions. At 9.18 the 4.45 a.m. train from London, and at 9.20 an express from Sheffield come in from the south almost side by side into No. 14 and one of two bays on the west side of the station. The former has on the rear a through van with mails and newspapers, and the latter a through passenger coach, both bound for Glasgow, which are collected by a small shunting engine and held in readiness at the south end of the station. Twelve minutes later a restaurant car express from Leeds, with a "Shire" 4-4-0 at the head, comes into No. 5 platform, and runs through to the north end, there collecting a large complement of passengers for Newcastle, Edinburgh, and Glasgow. The second of the shunting engines at the south end of the station moves up and collects a coach off the rear end of this train for Scarborough, and draws it back to the south end of the platform ; then the shunting engine with the London van and the Sheffield coach moves quickly up the centre down road, backs these vehicles over the cross-over on to the waiting train, and retires to other shunting duties.

Meantime things have been busier still at the north end. At 9.18 a.m. an express has come in from Sunderland and Stockton for Leeds, with through coaches on the rear for London ; this runs through to the south end of No. 4 platform, the London portion, which is drawn back by a shunter to the north end, leaving at 9.27, and the Leeds portion two minutes earlier—9.25. At 9.22 a "slow" comes into one of the north end bays from Harrogate, and an express from Hull into another, three minutes later. In a few minutes it is time to start the Glasgow express, at 9.38 a.m., on its 80 miles' non-stop run to Newcastle. It is followed into No. 5 platform, at 9.41, by an express from Normanton to Scarborough, on to the rear of which the waiting shunting engine, with the Scarborough coach off the Leeds to Glasgow train, now backs its load. Five minutes before this an express from Newcastle to Bournemouth has run in from the north, continuing to the south end of No. 4 platform, and stopping at 9.36 a.m. The coaches are London and North Eastern and Southern Railway stock on alternate days. After dropping its York passengers the engine draws the coaches forward, and backs them into one of the bay platforms on the east side, in order to evacuate No. 5 for the Newcastle to King's Cross express, which is due at 9.51 a.m., after a forty-three minutes run over the 44.1 miles from Darlington. As this flyer arrives, it is seen to have next to the engine a coach in L.M.S. red livery, and then a green Southern coach, the first labelled "Bristol" and the second "Bournemouth," but bound for their destinations by different routes—the first via Derby, Birmingham, Gloucester, Cheltenham and Bath, and the second via Nottingham, Leicester, Banbury, Oxford, Reading, Basingstoke and Southampton. Couplings are quickly undone, and the "Pacific" engine at the head of the London train—which is working through over the 268 miles from Newcastle to King's Cross—draws forward to allow a shunting engine to seize the two "foreigners," and to work them into the adjacent bays. The Southern coach is attached to the train which arrived from Newcastle at 9.36 a.m., and the L.M.S. coach to a train of L.M.S. stock which also is waiting in readiness.

There is now a general exit. From the south end the London express leaves at 9.57 a.m., running non-stop to Grantham, eighty-two and three-quarter miles away. It is followed at 10 a.m. by a fast train of the L.M.S. for Manchester and Liverpool from the opposite side of the same platform, and by an express for Leeds, starting simultaneously from tlie north end of No. 4, the two trains running parallel to each other as far as Church Fenton. At 10.10 a.m. the L.N.E.R. Bournemouth train leaves, followed at 10.15 a.m. by the L.M.S. express for the same destination, which will follow in its tracks almost to Rotherham. Then, at 10.25 a.m. a train which has been made up in the sidings at the north end, and has followed the London express into No. 4 platform, leaves for the Eastern Counties, using the London line as far as Doncaster, and with through coaches for Norwich, Lowestoft, Ipswich and Harwich. From the north end the Normanton train, with the through coaches from Leeds, gets away for Scarborough at 10 a.m., and at 10.05 a.m., simultaneously from No. 14 platform (outside the wall) and one of the bays on the east side, a semi-fast departs for Newcastle, Edinburgh and Perth, and an express for Hull. Interspersed with all this movement of trains through the station, engines have been brought from the sheds on to their trains ; coaches and train-sets have been put into their platforms, coaches dropped off arriving trains and not continuing farther have been taken away for stowage ; horse-boxes have been transferred from train to train, and other minor operations have been performed. Such details give an idea of the complications of coach-working rosters, and an inkling of the organization required to plan the work of a great station to run smoothly and to time.

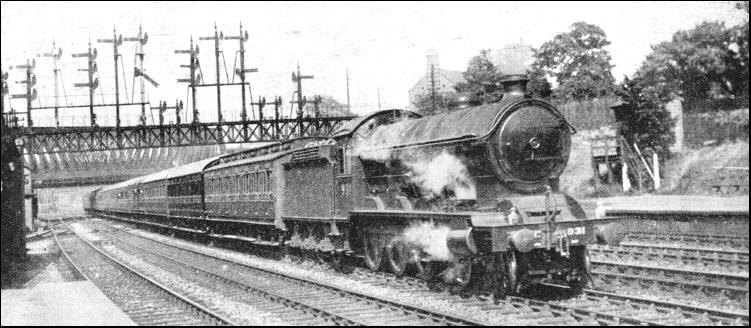

From ten o'clock onwards comparative peace descends on the great station, but not for very long. By half-past eleven matters begin to liven up again, with the arrival from Newcastle of the through express for South Wales, which has a long cross-country journey ahead, when it starts again at 11.42 for Sheffield, Nottingham, Leicester, Banbury, Cheltenham, Newport, Cardiff, and Swansea. Meantime, if this be the height of the summer season, the southbound "Scarborough Flyer" has also arrived at the same moment, and after a five minutes' halt, during which the 4-4-0 locomotive used from Scarborough gives place to a big "Pacific," the mile-a-minute dash to King's Cross begins at 11.35 a.m. Soon after midday trains begin to roll in from all directions—at 12.19 a.m. the first morning service from Edinburgh to King's Cross ; at 12.28 p.m. a train of the L..M.S. Company from Worcester and Birmingham ; at 12.23 another train of the same railway from Liverpool and Manchester; while at 12.10 p.m. a southbound L.M.S. express, which has picked up a through coach from Newcastle off the Swansea train, leaves for Birmingham and Bristol. Another temporary lull, and then comes all the activity connected with the "Flying Scotsman" expresses, both northbound and southbound, with which various very important connexions are made. First of all, at 1.10 p.m., there arrives a "semi-fast" from London, which at Doncaster has collected the through coaches off the "North Country Continental," bringing passengers from Harwich who have crossed the North Sea from the Hook of Holland and Antwerp. At 1.16 a smart Diesel-electric rail-car brings in Leeds people who want to board the "Scotsman" ; and at 1.31 the famous train itself draws majestically into No. 5 platform. Engines are no longer changed here, as the engine from King's Cross runs through to Newcastle. If it is the height of the summer season, of course, the "Flying Scotsman" passes slowly over the centre road, admired by all onlookers, on its non-stop course to Edinburgh, and a few minutes later the "Junior Scotsman," which makes the ordinary stops at Grantham, York, Newcastle, and Berwick, follows in. Immediately after the start of the "Flying Scotsman" for Newcastle, at 1.36 p.m., an important through L.M.S. express from Liverpool to Newcastle draws into No. 14 platform at 1.42, and has a wait till 1.55 before proceeding on its way. About this time things become busier in the southbound direction also. At 1.50 an express from Newcastle, which has run the last thirty miles from Northallerton on a sharp timing of 31 minutes, puts in an appearance, followed, at 2.12, by the up "Flying Scotsman," which runs through to the south end of No. 4. Following that, again, is another express from Scotland, at 2.23, with through coaches for Oxford and Southampton, and also for Continental passengers proceeding to Harwich. The "Scotsman" has left for London at 2.17 p.m. ; then, in connexion with the 2.23 arrival, connecting trains spread out, "fanwise," at 2.33 for Leeds, 2.35 for Manchester and Liverpool by the L.M.S. route, 2.35 for Hull from the north end of the station, 3 p.m. for Sheffield, Oxford and Southampton, and 3.17—another L.M.S. train—for Birmingham and the West of England. From 4.30 to 6.30 p.m., matters are brisk again, reaching their "peak" when the 1.20 p.m. express from King's Cross to Edinburgh arrives from the south, and the corresponding 2.05 p.m. express from Edinburgh to London from the north. The latter brings on its tail a through coach from Aberdeen to Penzance—the longest run in Great Britain of any through passenger vehicle, as the coach covers all but 800 miles on its journey, and takes twenty-one hours to do it.

Many thanks for your help

|

Share this page on Facebook - Share  [email protected] |