|

|

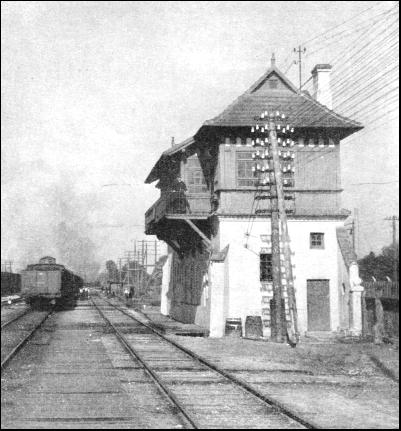

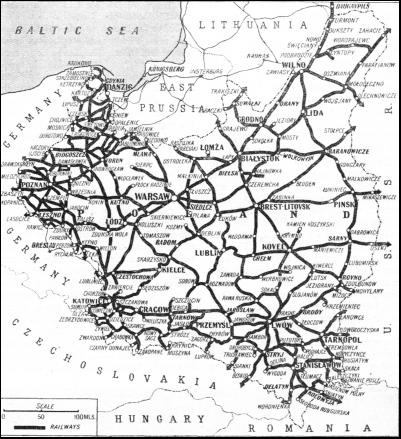

No country has had to face such a gigantic task of railway reconstruction within the last decade as the republic of Poland. Although Warsaw, the capital, is only a journey of some twenty-seven hours from London, comparatively few people visited Poland until recent years, but now that country attracts large numbers of tourists. The area of Poland is about 152,000 square miles, and the population is more than 33,000,000. The country is thus nearly twice the size of Great Britain, and contains about three-quarters of its population. In the past Poland was the prey of her neighbours, and in 1795, after two previous partitions, Russia, Prussia, and Austria divided the whole country among themselves, and thought that they had finally obliterated its existence as a free country. But they reckoned without the Pole. The republic of Poland was proclaimed in November, 1918 ; independence was guaranteed by the Treaty of Versailles. Thus, after an eclipse of over 120 years, Poland regained her entity as a nation. Her troubles, however, were not yet over, as war broke out with Russia in 1919. After Warsaw had been in imminent danger of surrender, a Polish counter-attack drove back the Russians, and a peace treaty between the two countries was signed in March 1921. Thenceforth Poland was able to deal with her problems of reconstruction. The Ministry of Communications, which took over the railways of the new state, was faced with the task of repairing and co-ordinating lines that had formerly belonged to three different countries—Germany, Austria, and Russia. During the war of 1914-1918 the whole of Poland had been one gigantic battlefield, and all the railways had been under gunfire and had been either destroyed or seriously damaged. Naturally, no maintenance of the permanent way or of the rolling-stock had been attempted.

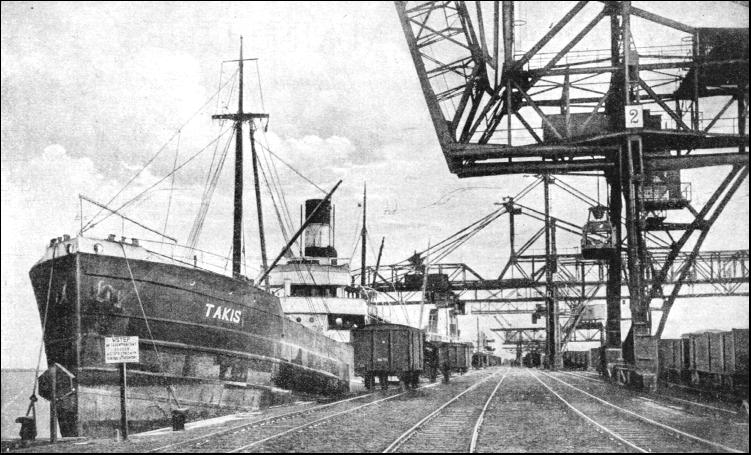

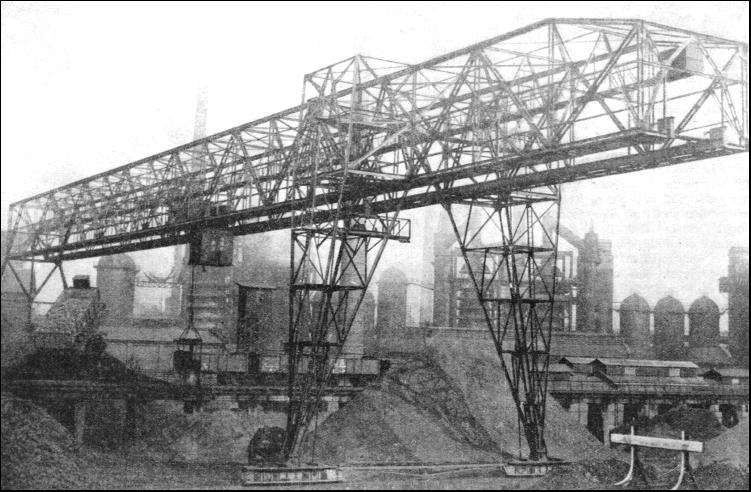

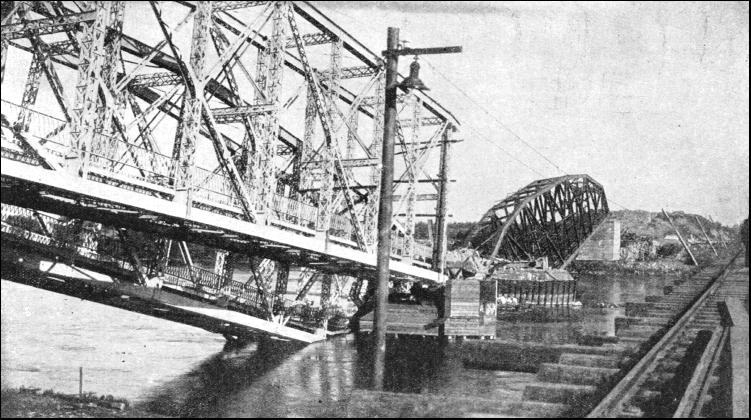

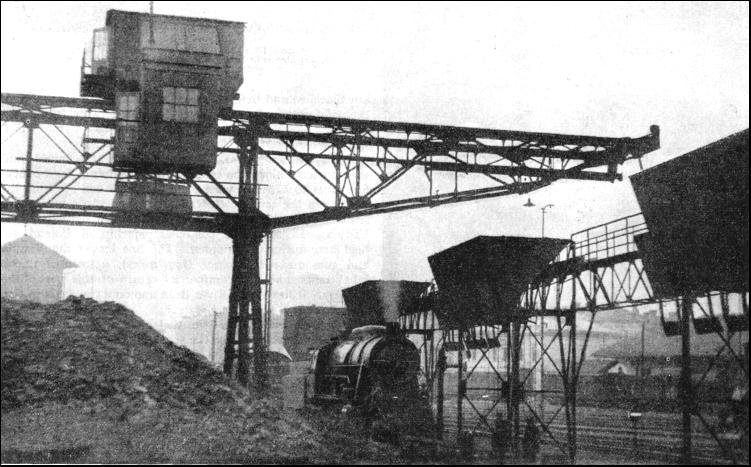

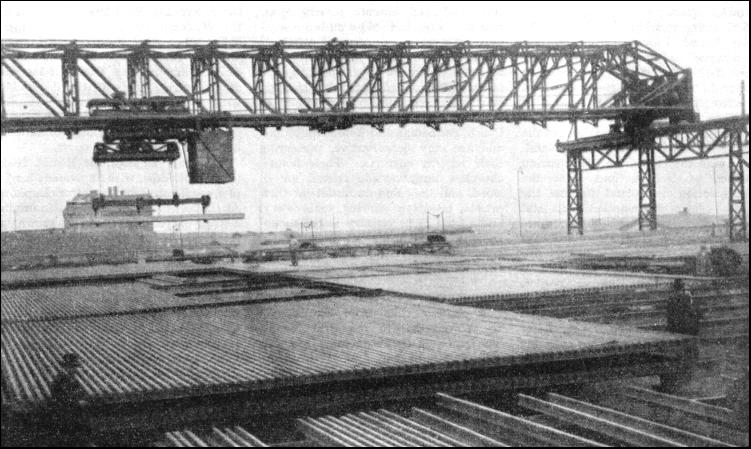

The Russians had wrecked bridges and other railway works to hamper pursuit as they retreated, and although the Germans, in their advance, had repaired the lines to a degree sufficient for military operations, they were not primarily concerned with the peace needs of the country. The new State, therefore, found the railways in a deplorable condition. The following figures will give an idea of the havoc that had been wrought in Eastern Poland. There had been destroyed eighty per cent of the bridges, seventy-seven per cent of the water towers, fifty-four per cent of the warehouses, and thirty-three per cent of the houses of the railway personnel. The permanent way had suffered less, perhaps, from high explosives than from being left without repair for some four years. Here and there the warring armies had removed miles of track, or had blown up junctions and points. But this damage was not so very great in proportion to the total length of the lines The neglect of worn out rails and the use of rotten sleepers had caused more serious damage, and it was to these factors that the lamentable conditions of the railways after the war were due The rolling-stock delivered to Poland after the war by the former occupants of the country was not only in bad condition, but was also mixed in origin and design. The making of spare parts was rendered difficult by the absence of drawings. At one time there were no fewer than 155 different types of locomotives. The railway administrators had to work out the best method of resuscitating a system with only a fifth of its bridges intact, with an unsafe track, and with inadequate and dilapidated rolling-stock. The problem was not only the reconstruction of the destroyed lines and buildings, but also the construction of new railways adapted to the new requirements of Poland as a sovereign state. Reconstruction has absorbed most of the funds available, and the work is not yet complete. Twenty-four per rent of the bridges, thirteen per cent of the station buildings, fifteen per cent of the water towers, ten per cent of the warehouses, and fifteen per cent of the houses for the personnel have, at the time of writing, still to be rebuilt. Both the volume and the direction of the traffic have been radically altered by the changed political and economic conditions of the country, and the building of second tracks or supplementary crossings has become necessary on many lines. This has caused a need for new stations, new supply facilities. and new locomotives. Most of these extensions are wanted mainly on the lines connecting Silesia with the Baltic ports. Much of this work has now been completed. Another great task was the rearrangement of several big junctions, especially that of Warsaw. The first section of the work at Warsaw has been finished, and the remainder of the work is nearing completion. One part of this large extension work, the electrification of Warsaw Junction, undertaken by a British company, deserves special mention, Work on the electrification of the underground section of the junction and of the suburban lines is in hand. The plans of the extension provide also for the erection of a new central station at Warsaw. The new standard gauge railway, 320 miles long, from the Silesian coalfield to the Baltic port of Gdynia, which was constructed in 1933, is operated by the French company that built it. The growing traffic at Gdynia demands constant extensions of the railway services and the laying of sidings on which goods wait for shipping.

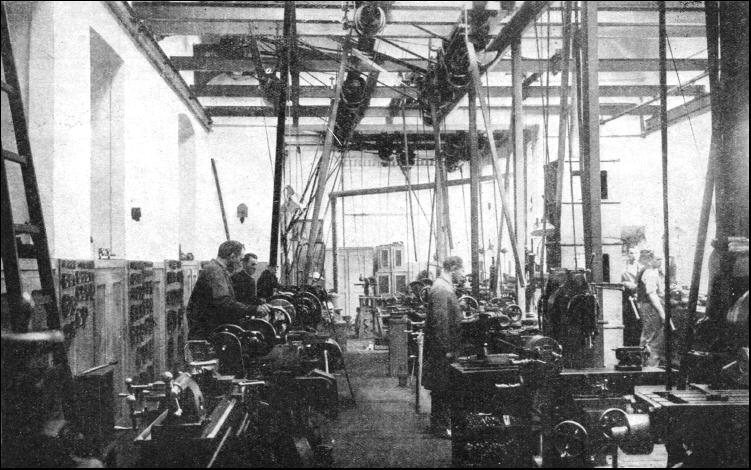

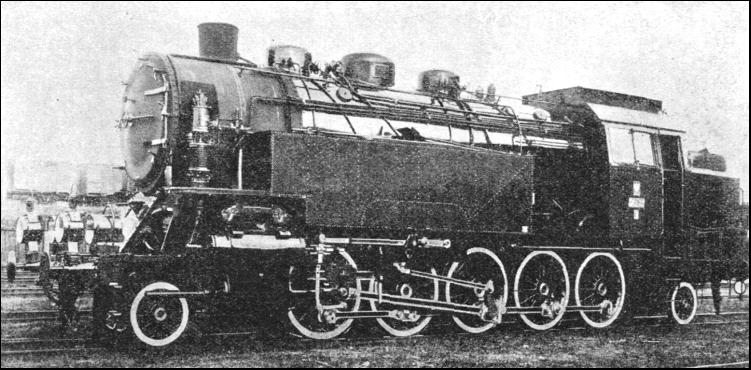

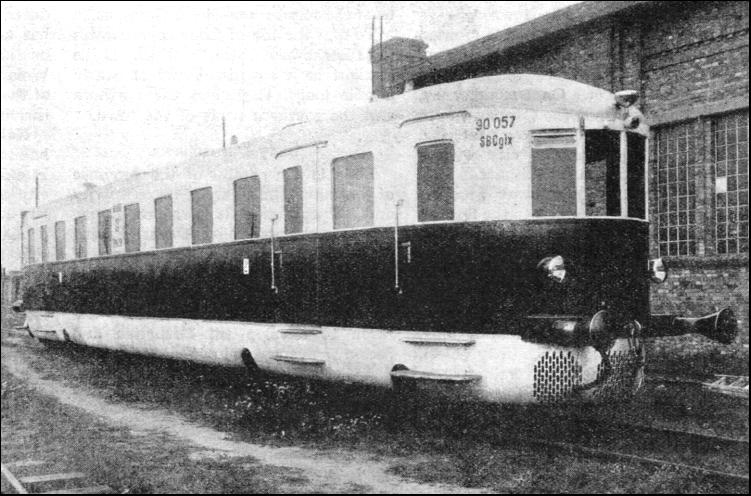

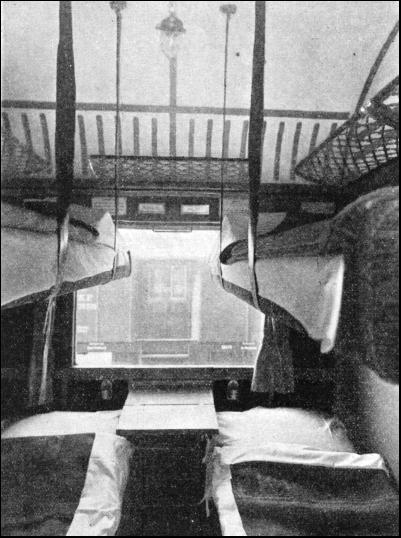

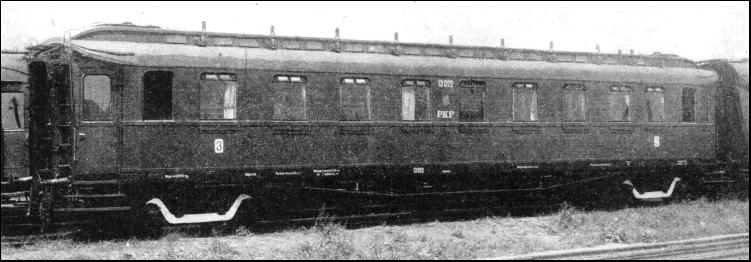

With the improvements in rolling-stock, the administration has had to strengthen bridges and improve the track. In spite of the enormous work and outlay caused by reconstruction, new lines totalling 820 miles in length have been built since 1919. The total mileage at the time of writing is 11,500 miles, about 90 per cent of which is owned by the State, but this mileage is not adequate. The railway system of the eastern provinces, formerly occupied by Russia, is ripe for improvement. Lines of a total mileage of 850 to cost some £20,000,000 are planned for the immediate future. The improvements to the rolling-stock followed the rehabilitation of the track. In the first years of independence Poland had to buy rolling-stock abroad, but new locomotive factories have appeared. These not only supply the needs of the country, but also export locomotives and coaches. Between 1931 and 1934 engines were exported to Bulgaria, Russia, Latvia, and Morocco. Poland has also built steel dining-cars for the International Sleeping Car Company which are being run over the railways of many European countries. On some services rail-cars have been introduced. Three types have been ordered from Polish factories. The first is an express rail-car suitable for long runs, and capable of a speed of eighty miles an hour ; the second is for tourist service and is designed to negotiate mountain gradients ; and the third is for suburban passenger traffic. The two latter cars are designed for speeds up to sixty five miles an hour. After the economic depression of 1932 the Polish railways regained ground, the number of passengers increasing to over 124 millions. The return to prosperity is largely due to the efforts of the administration to adapt the service to the requirements of the public. The "popular" trains are one example of this policy. These trains enable people to explore the whole country at a very cheap rate In one month—September, 1934—they carried 200,000 passengers. The goods traffic also is improving. An innovation showing the enterprise of the Ministry of Communications is the "train-hotel," organized in the summer of 1934 for a thirteen-days' "cruise" of Europe. Starting from Warsaw, the train went on a tour through Germany, Belgium, France, Italy, and Austria, returning to Warsaw on the last day. The eleven luxury cars of which the train was composed had a total of 260 berths. Each compartment accommodated four passengers, and was provided with comfortable beds, which were folded up in the day-time. Special measures were taken to reduce sway and rattle when the train was travelling at speed. The train travelled at night, so as to leave the day free for sightseeing. This mode of travel may be contrasted with the British cruising train "Northern Belle." The "Northern Belle" usually stops all night in a siding and cruises. by day, so that its passengers may enjoy a holiday away from cities. The Polish "train-hotel" took its passengers by night across country to enable them to see the cities by day.

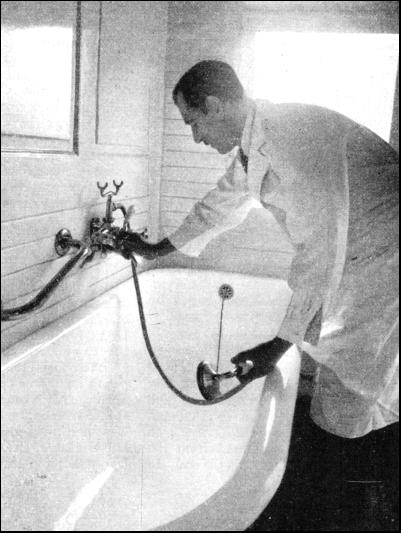

In addition to the restaurant car, the "train-hotel" was equipped with bathrooms, a hairdressing saloon, a bar, and a coach fitted out as a dancing hall. This coach had a special floor and its own band. The passengers, therefore, were able to enjoy all the amenities of a first-class hotel while touring through Europe. Thanks to its geographical position Poland offers the most natural and direct route across Europe between the Baltic ports of Danzig and Gdynia and the Romanian Black Sea ports. The early trader-explorers followed the great rivers and vast plains on their route across Europe, and the recent development of Poland's railways is restoring the importance of this historic route. The name Poland—Polonia in Latin and Polska in Polish—means the country of the plains (pole = plain). The greater part of the country therefore offered no formidable obstacle to the railway pioneers, except for the rivers. The first Polish railway, forming part of the line from Warsaw to Vienna, was begun in 1845. The surface is not, however, all level, but consists of four different varieties of country. A small area of the Baltic coastland in the north has slopes rising to some 600 ft. ; south of this begins the great Polish Plain. Beyond the plain is a region of low plateaux ; and in the extreme south is a depression after which rise the northern slopes of the Carpathian Mountains, which the railways are opening up as winter resorts. Thus the countryside is flat and densely populated in the western and central parts, mountainous in the south, and thickly wooded and sparsely populated in the east.

The territory known as the Polish Corridor, which separates East Prussia from the rest of Germany, is interesting to the railway enthusiast. Trains from Western Germany to East Prussia are hauled across Polish territory by Polish locomotives. The weight of these trains has increased to such an extent that new locomotives, the most powerful in Poland, have been made in Polish workshops and put into service. The city of Danzig was made a free port under the Peace Treaty, and the lines round it were taken over by Poland in 1920. But, to provide an outlet for the export of Silesian coal, a new railway, keeping entirely within Polish territory, was built, and a new port was constructed at Gdynia, which is one of the most recent towns in Europe. In 1919 Gdynia was a fishing village of 1,200 inhabitants, with some attractions as a seaside resort. In 1924 the authorities decided to make it a port, with the result that the population had increased to 50,000 by 1931, and has grown rapidly since. The network of railways in the provinces of Pomorze and Poznan, which constitute north-western Poland, is very close, very few places being more than seven miles from a railway station, The provinces of Warsaw and Lodz are not so fortunate. Expresses with restaurant and sleeping-cars are run from Warsaw to Poznan (Posen) and Zbaszyn, via Lodz or via Torun (Thorn) ; from Warsaw to Danzig via Grudziadz or Torun ; and from Poznan to Danzig, via Bydgoszcz, and to Cracow via Katowice.

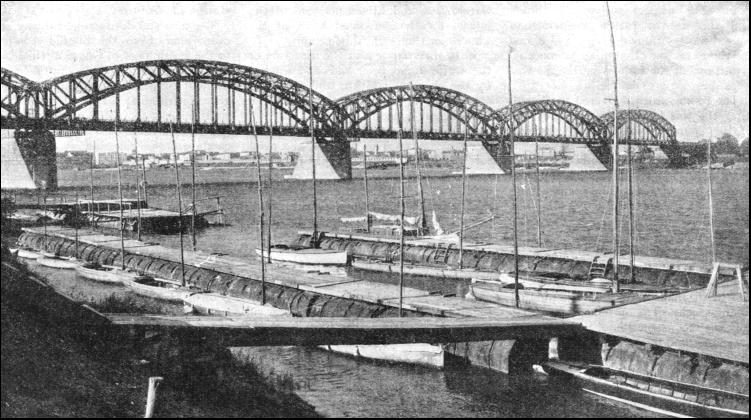

The line from Warsaw to Poznan and Zbaszyn forms part of the Warsaw-Berlin route. The section connecting Kutno with Strzalkowo was built in 1922 ; it provides the shortest route between Warsaw and Poznan. The country is more or less flat. After having left Warsaw, the train proceeds to Sochaczew (32-1/2 miles away), a town of some 7,000 inhabitants, situated on the River Bzura. This was the Russian-German front line in 1914-15, and there are numerous war cemeteries. On a small hill are the ruins of a 15 th-century castle of the Masovian dukes. Five miles north-east is Zelazowa-Wola, the birthplace of Chopin, the composer. He is commemorated by an obelisk. Lowicz (fifty miles), a town with 16,000 inhabitants, is a junction for Lodz and Skierniewice. Lowicz was formerly the residence of the Archbishops of Gniezno, primates of Poland. Before the partition of Poland the town was famous for its horse fairs and for the manufacture of weapons. The two Baroque towers of the collegiate church dominate the town. The church is rich in artistic and historic monuments, and contains the tombs of twelve primates. The beautiful national costumes worn by the peasants are to be seen and admired on Sundays and feast days. The women wear bright woollen skirts woven on their hand looms, and the sight of the peasants in procession on the feast of Corpus Christi attracts crowds of visitors. Kutno (eighty-three miles from Warsaw), with 26,000 inhabitants, is a junction of five lines. The line to Lodz, sixteen miles to the south, was built in 1925 North of Kutno a line of twenty-eight miles runs to Plock ; this was built in 1923. Plock, a town of 33,000 inhabitants, picturesquely situated on a hill on the right bank of the River Vistula, is one of the oldest towns in the country, and was the capital of the dukes of Masovia and Poland from 1080 to 1138. A fine bridge spans the river.

Returning to the main line at Kutno we proceed to Kolo (114 miles), one of the most beautiful of the smaller towns, situated on the River Warta. The train then passes on to Konin. From this town a narrow-gauge line runs twelve miles north to Kazimierz Biskupi. The palace of the Mankowski family stands in a large park, where a granite monument marks the spot where Prince Patkul of Courland was torn asunder by horses in 1707 by the order of Charles XII. The country here is rich in forests, hills, and lakes, the lakes forming the chain of the Lakes of Kujawy, the most beautiful of which are the long narrow lakes of Wasosze and Slesin. The little town of Slesin, on the lake, has a triumphal arch erected in 1806, commemorating the entry of Napoleon into the town at the head of the French army. From Konin the train passes the former Russian-German frontier between the towns of Slupca and Strzalkowo, proceeds through Wrzesnia and on to Poznan. Poznan (Posen in German) is the oldest town in Poland. It was the capital of the country in the tenth century. The Tartars destroyed the city in 1241, but it was rebuilt in 1257. In 1656 and in 1704 it was plundered and burnt by the Swedes and Prussians, and remained in a neglected condition for a long time. In 1793, after the second partition of Poland, it was occupied by the Prussians. The town was united by the Treaty of Tilsit with the Grand Duchy of Warsaw from 1806 to 1815, when it was restored to Prussia. From 1815 to 1918 it remained Prussian. In the nineteenth century Poznan was the chief centre of the Polish national movement in Prussian Poland.

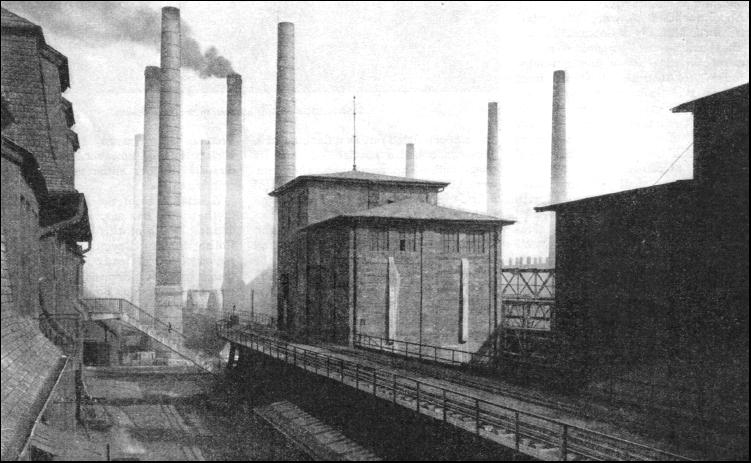

After the failure of the insurrection of 1831, the Germans began to remove the Poles from official positions, and forbade the language to be spoken in schools. After the Franco-Prussian war, in 1871, the German rule became more oppressive. The town was so strongly garrisoned that it was reputed to be the strongest fortress in Germany. Nevertheless, the Poles remained as nationalist as ever. On December 27, 1918, they disarmed the German troops and raised the Polish flag over the city. To-day it is a thriving city with a quarter of a million inhabitants. From Poznan the railway proceeds another twenty-two miles to the frontier station at Zbaszyn, an important junction on the line. The train here leaves Poland and goes on for Berlin or Paris. The route from Warsaw to Poznan, by way of Lodz, is 239 miles long. Before entering Zielkowice (fifty miles), a suburb of Lowicz, the train follows the former route. It then goes on to Zgierz (eighty miles), the first town in the province of Lodz, and, after Lodz, the second centre of the wool industry. Lodz (eighty-seven miles) is an industrial town with 600,000 inhabitants, and is second in population only to Warsaw. It is the Manchester of Poland, and is the centre of the textile industry. The horizon is darkened by smoke from the chimneys of the busy factories. One factory alone employs 12,000 workers. During the war the neighbourhood was the scene of much fighting in 1914, and most of the factories suffered for years from the requisitions of the Germans. To-day the life of Lodz concentrates in Piotrkowska Street, which is as straight as a sword-cut and is nearly a mile long. It divides the northern and the southern parts of the town. Lodz is the capital of the province of that name, but, despite its prosperity and its population, it is ranked among the second-class Polish towns, having no artistic or historical monuments of interest. It is an industrial town constructed without any definite plan. Lodz is a modern town, as it did not begin to develop till Bohemian and Saxon weavers were introduced in 1820, and the first weaving mills were started. It was in those days a mere village of some 800 people ; but from then it grew with surprising speed, becoming a city with half a million inhabitants by 1914. Forty per cent of the inhabitants are Poles, forty per cent are Jews, and the remaining twenty per cent are Germans. As recently as 1930 the town erected a monument to Tadeusz Kosciuszko, the Polish patriot who fought for the United States in the War of Independence and directed the last resistance to the partition of his country. Pabjanice (ninety-six miles), an industrial town of 50,000 inhabitants, has an older history. It concentrates on the manufacture of linen. Zdunska Wola (113 miles from Warsaw), a town of the same size as Pabjanice, is another thriving place.

Kalisz (157 miles), with 55,000 inhabitants, has roots deeper in history. It existed in the Roman epoch, was a city of note in the Middle Ages, but in the nineteenth century it fell into a decline for the very pertinent reason that there was no railway. It did not revive until a railway was constructed as late as 1905. Then it had the misfortune to be close to the Russian-German frontier, with the result that its war troubles began as early as August 2, 1914. Reconstruction is not yet entirely completed. Most of the monuments were destroyed, while nearly all the public buildings are new. The line passes through the small town of Kornik, and continues to Poznan, which is 243 miles by this route. The route from Warsaw to Poznan by way of Torun is 234 miles long. It was formerly the main route between Warsaw and Poznan and the main railway connexion between Russian and German Poland. From Warsaw the train proceeds to Kutno (eighty-three miles), over the route previously described, and then turns north-west. Wloclawek (117 miles), with 60,000 inhabitants, lies on the left bank of the River Vistula. The Bishop's Palace, which was damaged by the Bolshevists in 1920, has been repaired. From Aleksandrow (140 miles), until 1914 the Russian frontier station, a local line runs nearly five miles north to Ciechocinek, the largest spa of central and northern Poland, the bathing establishment possessing about a dozen salt springs. These dozen iodine-bromide springs are the most productive mineral springs in the country, and they yield half a million litres of salt per hour, which is extracted by a large plant. Torun (Thorn in German : 152 miles), with 60,000 inhabitants, the capital of the province of Pomorze, lies on the right bank of the River Vistula. A beautiful iron bridge, more than half a mile long, which was built in 1853, spans the river; a second bridge was begun in 1928. The famous astronomer, Copernicus, was born in the town in 1473. The campaign of the German Order of the Teutonic Knights against the Prussian heathens in 1230 began from Torun. As the chief centre of the corn trade—the corn being transported by boats on the Vistula to the Baltic—Torun became one of the wealthiest towns on the river. Still surrounded by old walls, it is very picturesque. Inowroclaw (167 miles) is a town from which a branch line runs south to Lake Gopio, near which is the small town of Kruszwica. On a small peninsula jutting out into the lake stands the Mice Tower of the fourteenth century, a relic of the castle of Casimir the Great, which was destroyed by the Swedes. According to a legend, Prince Popiel of Kujawy was eaten by mice in this tower. The main line passes through the towns of Mogilno and Trzemeszno to Gniezno (202 miles), which has old monuments and modern factories, and then goes on to Poznan.

From Poznan an important line runs south to Rawicz, near the German border, where it connects with the line from Breslau. Mosina, which is twelve miles from Poznan on this line, is in an interesting locality. Nearby, at Rogalin, is the palace of Count Edward Raczynski, in which the French-Saxon Treaty was signed in 1806. A collection of modern Polish pictures is housed in a picture gallery in a park famous for its thousand-years-old oaks, and the circumference of the largest tree measures over 30 ft. Leszno (forty miles) and Rydzyna (fifty miles) are other towns containing beautiful and historic buildings. Leszno is connected by other lines with Jarocin, with Ostrow, and also with Zbaszyn ; the network of railways has been closely constructed in this area. From Poznan other lines run to Krzyz, in Germany, and towns near the border. The line linking Poznan with the new port of Gdynia runs chiefly across a region near the western border of the province, where practically no important towns are to be found. Beyond Kcynia the train passes extensive marshes, and crosses the River Notec before going north to the important junction of Chojnice (106 miles), a town of 12,000 inhabitants. It is a junction for lines to Berlin, Königsberg, and Laskowice. Chojnice lies in a hollow between the hills, and has many historic buildings. The marshy ground which formerly surrounded it has been converted into meadows, but in the old days the marshes protected it to such good purpose that the Teutonic Knights held it for a long while in the Thirteen Years' War. When the Poles captured it in 1466 it was the last Teutonic town west of the Vistula to surrender. Fragments of the old walls and several bastions still remain. On leaving the town the train enters the district of Cashoubian Switzerland, called Zabory, meaning "beyond the large forests." This district has a charm that attracts lovers of nature. Remains of the national Cashoubian culture are found in these remote parts. The small village's are inhabited by peasants of noble descent. The long, wide lakes among the pine forests are the haunt of many birds. Owing to the sandy soil the peasants are poor, fishing and farming being their only occupations. Most of the cottages are thatched and built of wood, and there are a number of beautiful old wooden churches. At Koscierzyna (148 miles) the train follows the route from Warsaw to Gdynia, which will now be described.

From Warsaw the train goes to Torun (146 miles), and then proceeds along the left bank of the Vistula for twenty-five miles to Legnow, where the passenger can see from the window of the carriage the largest timber yards in Poland, situated near the mouth of the Brda, which here joins the Vistula. Regattas for the championship of Poland are held here during the summer. The line leaves the Vistula and goes on to Bydgoszcz (177 miles), a town of 12,000 inhabitants, and the commercial centre of this part of the country. It lies on the River Brda and on a canal connecting this river with the River Notec. The town was founded in the fourteenth century, and was highly developed by the seventeenth century, but the Swedes almost destroyed it in 1656. After the partition great efforts were made to Germanize the town. But it has quickly regained its Polish character, and it is now the second town in the province of Poznan.

After leaving the town the train passes northward on a line which was built to reach Gdynia without passing through Danzig. From Maksymiljanowo (183 miles) to Czersk Pomorski (235 miles) the train crosses a thinly populated district with no large towns. The line runs through the forests of Tuchola, which extend from the River Vistula to the western border. The trees are mostly firs, growing in the sandy soil. There are many lakes and rapidly flowing rivers in the forests. Settlements and cultivated fields are now being made in what, before the building of the new railway, was virgin forest. Emerging from the forest and going north, the train arrives at the town of Koscierzyna (248 miles) and enters Cashoubian Switzerland, with its wooded hills and lakes. Wiezyca (259 miles) lies at the foot of a hill which rises to the height of 1,086 ft. above the sea, and is the highest in this area. A little beyond this station the new line turns to the east, leaving the old one, which goes to Kartuzy, the centre of Cashoubian Switzerland. This town of 5,000 inhabitants owes its name to the monastery of the Carthusians, which was closed by the Prussians in 1826. There are no fewer than 173 lakes in this lovely district, which occupies the centre of the Polish Corridor. A local railway connects Kartuzv with Danzig. The train to Gdynia turns east and then north east, crosses the River Radunia, runs north, and, beyond Osowa (280 miles) it begins to descend from the Cashoubian upland towards the sea. In the distance can be seen the Baltic, and the port of Gdynia, 290 miles from Warsaw, is soon reached.

Another and shorter route of 255 miles from Warsaw to Gdynia is by way of Grudziadz and Tczew. From Warsaw the train runs along the eastern bank of the Vistula along the plain to Jablonna, and crosses the River Bug-Narew near its confluence with the Vistula, just before Modlin (thirty miles), a fortress built by Napoleon, to command the confluence. The forts here were destroyed by the Germans in 1915. A beautiful view of the rivers can be obtained from the bastions of the old fortress. Beyond Mlawa (eighty-two and a half miles) the train passes from the province of Warsaw to that of Pomorze. Beyond Dzialdowo (ninety-five miles), formerly the capital of the Masurian district which belonged to East Prussia, the train passes many war cemeteries and monuments. After Lidzbark (110 miles) the landscape becomes less monotonous, the Masovian plain giving place to wooded hills and lakes. Before reaching Brodnica (130 miles) the train passes the forests of the lakeland of Brodnica. There are in these forests over a hundred lakes, narrow, long, and very deep. They are typical of the glacier epoch, with very clear water and curiously cut shores where wild-fowl are numerous. Grudziadz (163 miles), a town of 64,000 inhabitants, lies on the right bank of the Vistula, and is the second largest town in Pomorze. Formerly a fortified city, it existed as early as the tenth century. After the first partition of Poland, Frederick II made it a powerful fortress to safeguard the Prussian grip on the lower courses of the Vistula. In 1807, during the Napoleonic Wars, the French besieged it for several months, and it did not surrender until the Peace of Tilsit. The commander of the fortress. General Courbière, was called the "Lion of Graudenz." He died and was buried in the fortress in 1811. The railway reached the town in 1878, and it became an industrial centre with an iron foundry and a factory for agricultural implements. The train crosses the Vistula by an iron bridge, 1,239 yards long, built in 1879. At Laskowice (176 miles) the train turns north for Tczew (222 miles), a town of 23,000 inhabitants on the Vistula, which here forms the boundary between Poland and Danzig. Five miles farther on the train crosses the border at just beyond Milobadz. On the left can be seen the hills of the eastern edge of the Cashoubian Switzerland, and on the right the fertile Danzig lowlands. After Danzig (242 miles) the train proceeds through the resort of Zoppot, regains Polish territory at Orlowo-Kolibki before reaching Gdynia (255 miles).

The Polish coast-line stretches for thirty-seven miles from Zoppot to the mouth of the Piasnica, and is divided by the peninsula of Hel into two parts, the Baltic coast, called the Great Sea, and the Bay of Puck, or the Small Sea. The territory of the Free City of Danzig has an area of 726 square miles and contains about 390,000 inhabitants. It is formed by the delta of the Vistula. The earliest mention of Danzig dates from 997, when it was the base of the missionary expedition of St. Adalbert, Archbishop of Prague, to the Prussian heathens. Until 1139 it was Polish ; it then came into the possession of independent Pomeranian princes of the Gryfit dynasty. The last of these bequeathed the city to Poland. After a period of strife it was occupied by the Teutonic Knights in 1308. It became a free city in 1466, under Polish rule. In 1793 it was occupied by the Prussians. The French held the city from 1807 to 1814, and in 1815 it was annexed by the Prussians, who retained it until the end of the 1914-1918 World War, when it became a Free City under the League of Nations. The hub of the railway system of Poland is Warsaw. The capital city, in the geographical heart of Europe, lies on the left bank of the Vistula, the great river which flows from the Carpathians to the Baltic. Some magnificent bridges span the Vistula at Warsaw. The city, which has 1,200,000 inhabitants, is linked by rail with many other European capitals. By railway London is twenty-seven hours distant, Berlin ten hours, and Paris thirty-one hours. Leningrad, Moscow, Vienna, Prague, Rome, Budapest, Bucharest, and Odessa are other capitals and great cities with which it is in direct communication by railway. Founded in the thirteenth century, Warsaw became in 1595 the capital of the Kingdom of Poland. It is the centre of the administration, legislative and cultural life of the country as well as being a great manufacturing town. It is the junction for all the main lines.

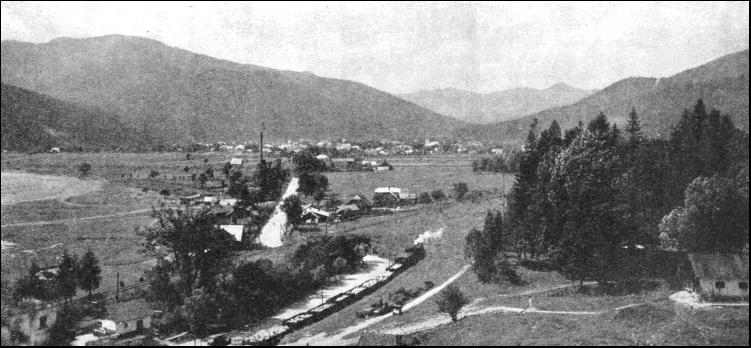

Apart from its railway communications with the Baltic, the big industrial centre of Lodz, and the important city of Poznan and the connexions with Germany, there are many important lines radiating from Warsaw. One important route goes through Bialystok, a textile centre, and on north-eastwards to Wilno (207,000 inhabitants), the principal city in the north-eastern provinces. The line proceeds parallel with the Lithuanian frontier and crosses the Latvian border at a point some 350 miles from Warsaw. Another line, branching east from Wilno, runs into Russia. The line from Warsaw to Moscow proceeds via Stolpce. Another line from Warsaw into Russia crosses the frontier at Mohylany, 317 miles distant. The line to Bucharest, proceeding south-eastwards from Warsaw, crosses the border at Sniatyn-Zalucze, 470 miles away. Zebrzydowice, to the south-west of Warsaw, is the gateway to Czechoslovakia and to Prague, Rome and Vienna. Cracow (Krakow), with a population of 232,000, is the capital of the province of that name, an ancient city and an important centre of arts and crafts. It lies on a railway which runs from Katowice (128,000 inhabitants), the capital of the province of Silesia, right across Poland through Tarnow (60,000 inhabitants) to Przemysl (60,000 inhabitants) on the San River. Przemysl became famous during the war as an Austrian fortress which withstood a long siege. This line goes on to Lwów, or Lemberg (316,000 inhabitants), where the railway station is the finest in Poland. Lwów was the capital of the Austrian province of Galicia, and after the reconstruction of Poland became the cultural centre of Eastern Galicia and also of the former Russian province of Volhynia. A network of railways extends in all directions from this fine city. Continuing east, a line goes to Tarnopol and the Russian border. The province of Tarnopol, known as Podolia, is dotted with ruins and historic monuments, and is very beautiful. The River Dniester has towering shores, covered with rocks or forests, and at one point flows through a canyon 650 ft. deep. The district between this river and the River Zbrucz, which forms the Russian frontier, has a mild southern climate which favours vineyards, and the growing of apricots and similar fruit. Zaleszczyki, near the Romanian frontier on a branch line, is the centre of this region, and is also a popular summer resort. The railway from Lwów to Warsaw passes the provincial capital of Lublin, a city of 100,000 inhabitants, on this line, fifty-four miles from Warsaw. Kazimierz, on the Vistula, the railway station for which is Pulawy, eighty-one miles from Warsaw, is the only city in Poland which has preserved its ancient aspect to a very great extent. The Carpathian Mountains curve in a wide arch along the southern frontier of Poland, and summer resorts, spas, tourist centres and ski grounds are scattered over the mountains and valleys. Stanislawów (80,000 inhabitants), the seat of a provincial government, on the railway from Lwów, is the starting point for excursions into the land of Hucules. The Hucules are a blend of Polish, Ruthenian and Romanian people, and are very conservative, preserving their ancient customs. Their homes, churches, and wayside crosses are of wood, and they find an outlet for their artistic talents in carving, embroidery, and rugs. Their country is the mountainous, wooded district between the rivers Czarna Bystrzyca, Prut and Czeremosz. A railway runs from Stanislawów to Woronienka, in the Prut Valley. The mountain resorts include Jaremcze, 1,700 ft.; Mikliczynu, 1,960 ft.; Tatarow, 2,200 ft., and Worochta 2,420 ft. above sea-level. The Czarnohora Mountains are over 6,500 ft. high, rising above Worochta. A narrow gauge forest railway runs from Nadwórna Station on the Stanislawów-Woronienka line to the valley of the Czarna Bystrzyca river. At the top of the valley is the village of Rafajlowa, under the Pantyr Pass, which became famous in the war. Near by is the region of the Gorgany Mountains, which lie between the River Prut in the east and the River Swica in the west. The region is the roughest and most sparsely inhabited in the Carpathians, and is covered with dense forests, above which tower rocky peaks, the highest being Sywula, 5,900 ft. Narrow gauge railways have opened it up for the special benefit of the tourist. West of this range an adjoining one, the Bieszczady Mountains, stretch from the Wyszkow Pass, the average height being 4,000 ft. Less wooded, they are more thickly populated, and can be reached by railway from Lwów and other centres. This district is popular with ski-runners, the slope at the Troscian (4,000 ft.) being the best-known in Poland, the village of Slawsko being the centre for the sport. The long range of the Beskid Niski (Lower Beskids), with an average height of 2,500 ft., stretches west from Lupków. At the feet of the Bieszczady Mountains a string of spas and resorts has grown up. At Morszyn, on the railway between Stryj and Stanislawów, is a mineral bitter spring (sodium sulphite), the only one in Poland, and one of the strongest in Europe. The spa is a centre for mountain excursions. One of the largest spas in Poland is at Truskawiec, which is connected by railway with Lwów. Other spas are Rymanow, on the Nowy Zagórz-Nowy Sacz line, and Iwonicz, on the same line, and only four miles away. The Carpathians rise to greater heights of from 3,600 to 4,000 ft., going west from the Tylicka Pass at Krynica. The most interesting part of this region is the district of the Pieniny Hills, which, forming a lateral spur, are not high but are very beautiful. The Dunajac River divides them into two regions and forms the frontier between Poland and Czechoslovakia. The highest point is Trzy Korony, 3,300 ft. Nowy Targ, on the Cracow-Zakopane line, is a centre for excursions. On the Nowy Sacz-Krynica line is Zegiestów, a noted spa ; but Krynica (1,850 ft.) is the most famous of Polish medicinal springs and attracts thousands of visitors each year.

Many thanks for your help

|

Share this page on Facebook - Share  [email protected] |