|

|

A modern steam locomotive grows from a heap of grey iron castings, rough steel plates, and forgings to a veritable giant of power and speed. But neither passengers nor goods can be carried on an engine, and railway travellers would undoubtedly find the footplate more interesting than comfortable. The design and construction of coaches and wagons is, therefore, an important feature of railway work. The building of rolling stock presents all kinds of difficulties, and numerous problems have to be solved. Technical details of design are settled by the engineers, but other items call for the attention of many widely differing trades. To the work of the engineer on under-frames and wheels must be added the skill of the carpenter and joiner and the art of the upholsterer and the painter, coupled with many efforts of other tradesmen—heating, lighting, and ventilation experts, and electricians and plumbers. The construction of the undercarriage, both for coaches and good wagons, may vary in detail, but the underlying principles are the same in all instances. The undercarriage framework generally consists of two channel girders of [ section, or of sole-bars connected at either end by buffer beams and strengthened by cross-bracing. The frames of long coaches are usually provided with tie-rods or angle-girders to give additional support in the centre. The importance of this strengthening will be appreciated when it is borne in mind that a modern coach may be 70 ft. long and over 9 ft. wide. All parts of the undercarriage are designed to give maximum strength with the least possible weight. To obtain the best results from this combination the various members are often welded instead of being riveted together.

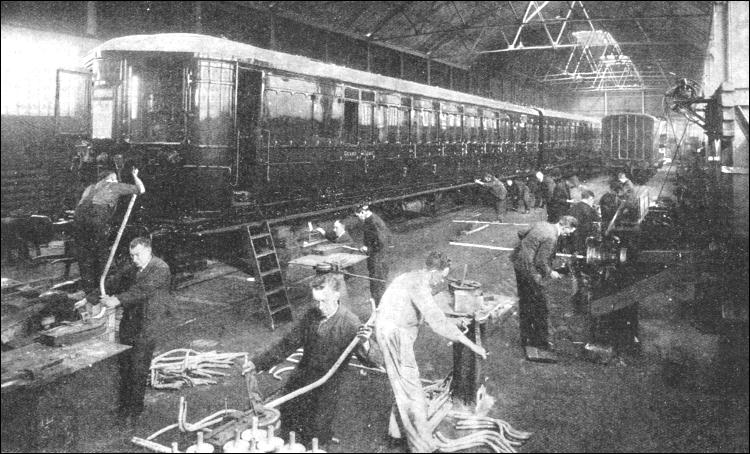

Bogie frames also are welded in many of the shops, and the wheels are turned and fitted to the axles in a similar way to those of the locomotives. The completed under-frame, with bogies attached, is then fitted with brake equipment and connexions for steam heating, buffers, and couplings. An important item is the train lighting equipment. All modern rolling-stock is electrically lit. Dynamos are bolted in position and coupled to the axles by driving belts. Accumulator cases are attached to the under-frames of the coach to house the electric storage batteries, which provide light when the train is stationary. Undercarriages are usually built in one of the engineers' shops, and are then drawn into the carriage erecting shop for final assembly of the woodwork and additions of the fittings and equipment. There are in Great Britain a number of famous firms that specialize in the building of coaching stock, not only for British railways, but also for service all over the world. The four large railway companies, however, usually make their own coaches and wagons, and construction is carried out on the most modern systems of mass production. Formerly the building of a railway carriage took about six weeks, with a small army of carpenters and joiners making the component parts and fitting them in place. Improved organization and methods of production have reduced the above time to a period of only six hours for the construction of the coach body, including the roof. Such efficiency has been rendered possible by the use of jigs for the accurate making of every part. Some of the most up-to-date woodworking machinery in existence is to be seen in the railway carriage shops, where the perfectly made components are produced "from the log." If we consider a typical carriage works, the first place of interest will be the timber yard, where tree trunks and baulks of timber are stored for use as required. First the logs are cut into planks of varying thicknesses. Drying sheds are used to condition the timber and ensure that it is properly seasoned. Carriage components are first cut to size by a circular or a band saw, and are then fed forward over a series of rollers to planing machines provided with high-speed revolving cutters that pare the wood away, leaving a perfectly smooth surface. Other machines cut mortises and tenons, and multiple drilling machines bore the holes to receive bolts and screws. A multiple boring machine at the L.M.S. Earlestown works can drill, in one operation, the sixty-five holes required in the sole-bar of a wagon.

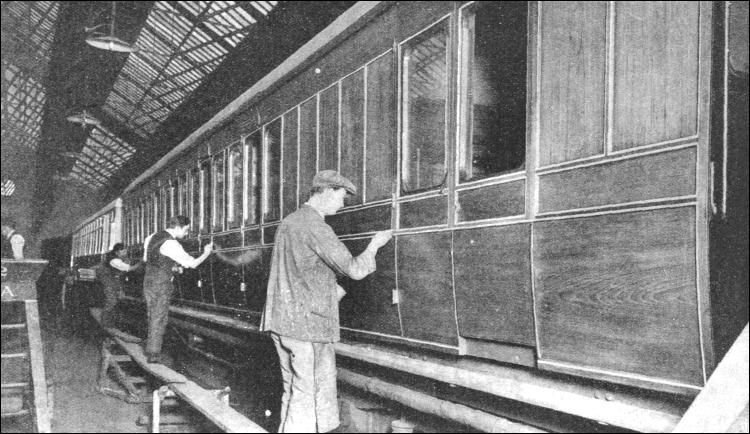

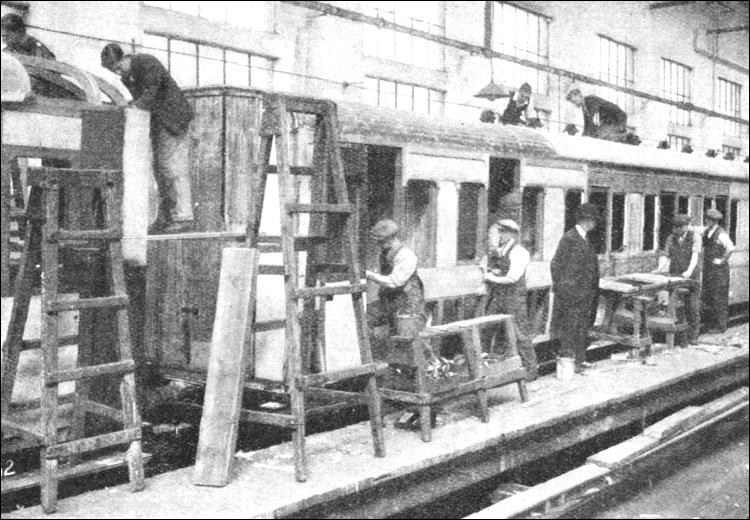

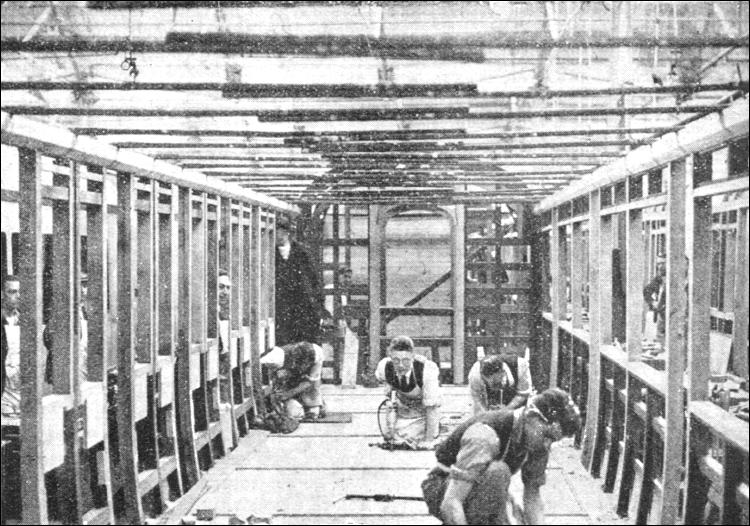

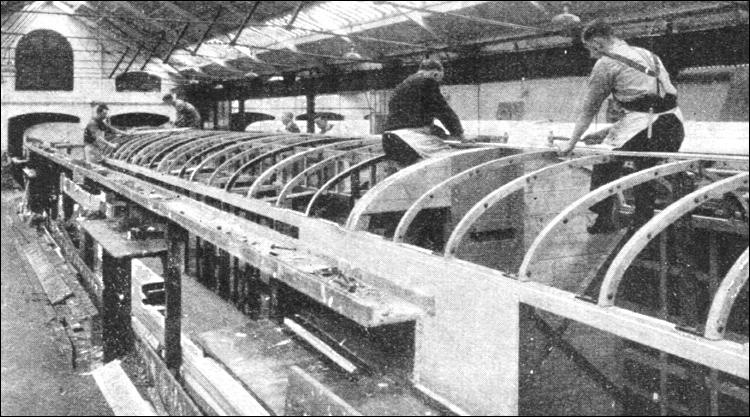

In these works the machining operations are so arranged that the timber flows in a continuous stream from one machine to another, and the rough wood is delivered as a finished component ready to assemble in the erecting shop. The whole process is facilitated by the provision of roller "run-ways" so arranged that timber is fed to the machines at the correct height. At no point in its passage through the shops is the work lifted by hand. The next process is the assembling of the component parts of the coach. At the Swindon carriage works of the Great Western Railway the procedure is first to construct the floor which will rest on the under-frame of the coach. Next follows the fixing of the side and end pillars and battens, after which the window lights and the rails are added. At this stage the coach somewhat resembles an early wooden ship, the floor representing the keel, and the upright portion the ribs that hold the outer planking. Inside compartments and corridor partitions are added next, and then the doors. Next, steel-plate panels are screwed on the outside of the body of the coach. Preparation of the roof follows. This is of steel plate screwed to roof "sticks" of oak that are bent to the required curvature. After seat frames have been fitted in the compartments, the body is placed on its undercarriage and run into the paint shop. Here it receives attention at the hands of the finishers, trimmers, and painters. The steel panelling on the outside of the coach is cleaned and prepared by workmen, who are followed by others who paint the metal surface. The lining of the paintwork and the affixing of crests and numerals is then undertaken; finally the whole of the exterior is given two coats of varnish. The undercarriage is painted with red lead before it enters the carriage body shop, and, after the addition of the coach-work, the outer parts of the frames and bogies are painted and japanned.

The upholstering of carriage seats is carried out in the trimming shop, where the linings and covers are cut out by a machine in layers about 4 in. deep. Sewing machines are then employed in the making-up process. The seats are afterwards fitted with springs, and the cushions stuffed with horsehair. In the trimming shop are made other articles such as blinds, guards' flags, towels, canvas vestibule gangways, leather dispatch bags, and window straps. Other departments set aside for the preparation of carriage components are the French polishing and the finishing shops. In the former, women are employed in staining, filling, and polishing the interior doors and decorative woodwork of the coaches. The finishing shop is allocated to the preparation of the interior woodwork of the carriages such as corridor, lavatory, and gangway doors, frames for seat backs, panelling, luggage racks, and woodwork for electric lighting. The wood refuse and sawdust in the sawmills and other shops is sucked up by large pipes and conducted to a furnace used to raise steam for shop heating and wood bending. Many remarkable machines are used in the production of a modern railway carriage. It is not generally realized that the machines used in shaping the timber turn out work that is accurate to a limit of a two-hundred-and-fiftieth part of an inch. The advantage of such accuracy is clearly demonstrated by the method adopted in the L.M.S. shops when fitting a roof to the body of a carriage. The completed roof is suspended over the coach and, after being lowered into position, is pulled down on the ends and sides of the vehicle by means of compressed air cylinders. Some ninety tenons thus slide into their appropriate mortices in one rapid movement. In the making of doors an ingenious machine holds the pillars and cross members, previously mortised and tenoned, in position by four hydraulic rams. The screws are then inserted and the door frame is complete and ready for attachment to the coach.

Screw-driving in a carriage works is facilitated by the use of a magazine-teed tool into which screws are fed through a funnel. The workman applies the screw to the hole, previously drilled in the woodwork, and the apparatus automatically drives it in. With the use of steel for coach building a new technique has been rendered necessary in construction. To take advantage of the strength and safety afforded by steel framework, and at the same time to reduce weight, welding is resorted to instead of the customary riveting. Welding is done by electricity or the oxy-gas blowpipe, and the process enables a lighter section of steel angle to be employed, as the joints are not weakened by the drilling of rivet holes. In addition, the rivets dispensed with represent a further saving in the total weight. In a modern steel coach the bogies are welded throughout, with the exception of the brake-work and axleguards, which require fairly frequent renewal. The floor is usually of steel sheeting welded directly to the coach under-frame, to which are also welded the steel sockets carrying the teak end and side pillars. The tops of the pillars fit into steel brackets welded to the "cantrails," the steel longitudinal members to which are welded the ends of the steel arch rails of the roof. The floor of a modern steel coach, particularly of a sleeping car, is carefully insulated to eliminate noise and vibration. The steel sheeting on the under-frame is covered with cork slabs cemented in place with a special composition material. Over the cork and composition is placed a layer of felt, and on this is laid linoleum, covered in both corridor and compartments by rugs.

The underside of the floor is sprayed with asbestos compound to a depth of 3/8 in. to deaden the noise of the wheels on the track. It is not generally appreciated that a main-line composite coach costs as much to build as a fair-sized country house. The expenditure on only one of these vehicles by a British railway company amounts to £4,500. The sleeping car costs even more, the expenditure amounting to the surprising figure of £5,500, which is more than half the cost of a main-line locomotive. A dining car costs £5,000, and even the humble suburban compartment coach cannot be built for less than about £4,000. Goods wagons are also built by mass-production methods. In some ways the construction of a wagon, for example, an open coal truck, resembles that of a passenger coach. The under-frame is built up of two [ section longitudinals or sole-bars pined by buffer beams or "headstocks" at the ends and cross braced to ensure rigidity. To the under-frame are riveted the axle guards that carry the axle-boxes, axles, and wheels. Continuous acting brakes are not usually fitted to the smaller types of wagon, but hand brakes are used that can be set to any required pressure to retard a goods train on the descent of a long and steep gradient. After delivery to the erecting shops the wagon under-frames are fitted with the timber bodywork with its strengthening angles and straps of steel. High-capacity wagons, especially those in use for coal traffic, are often made entirely of steel, and welding plays an important part in their construction. Another feature of modern wagon building is the use of roller axle bearings. Roller bearings reduce considerably the friction to be overcome in hauling goods wagons, and so enable longer and heavier trains to be hauled without increase of engine power. The forty-tons coal wagons, the largest size used on British railways, form an interesting contrast with those of the North American continent, where a capacity of 108 tons is common. Quite frequently goods wagons are built for special purposes, and their construction involves careful design so that they may be suitable for their intended purpose, and at the same time not place too great a strain on the permanent way over which they will have to travel. The cost of construction of wagons used on British railways gives an excellent indication of the enormous sums expended by all railway companies on their rolling stock. For example, a twenty-tons hopper coal wagon costs £250, while a twelve-tons mineral wagon is constructed for a sum amounting to £115. Covered twelve-tons goods wagons of normal design, with steel frames and fitted with vacuum brake equipment, cost as much as £200.

Many thanks for your help

|

Share this page on Facebook - Share  [email protected] |