|

|

The page, Across Australia by Train, tells the story of the Australian railway pioneers In particular it explains the early divergencies of view between the engineers of the various States, which have resulted in a multiplication of gauges causing some inconvenience in inter-state railway travel. These differences of gauge must be borne in mind in reading this page, which deals with the railways of New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, and Tasmania. To appreciate the development of Australia’s railways it is necessary to remember that in 1935 Australia was a federal commonwealth forming one of the self-governing Dominions of the British Empire, and is divided politically into six States: New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia, and Tasmania, of which New South Wales and Victoria are the most populous States. In addition, there is the relatively small Federal Capital Territory, containing the federal capital Canberra, and forming an enclave in New South Wales; and the extensive but sparsely populated Northern Territory, administered by the Commonwealth. The total area of the Dominion is nearly 3,000,000 square miles; its extreme measurements are 2,000 miles from north to south and 2,450 miles from east to west. This vast area in contained in 1935, about 28,000 miles of railways, a figure only 8,000 more than the railway mileage of the relatively small island of Great Britain. Over 2,100 miles, including the 1,051 miles of the Trans-Australian Railway, are owned by the Commonwealth; most of the remainder belongs to the various States, or is privately owned. The continent of Australia has no exceptionally high mountains, the highest peak, Mount Kosciusko, in New South Wales, reaching an elevation at 7,328 ft. only. There extends, however, from the north to the south an interminable mountain barrier called the Great Dividing Range, roughly paralleling the east coast at a distance of from 30 to 150 miles from the sea. The Dividing Range constitutes a formidable barrier to railway communication between east and west, and explains the severity of many main-line gradients. Among other mountain ranges, that of Mount Lofty in South Australia has proved a serious obstacle to the railway engineer. But despite the natural difficulties of the country, and the delays occasioned by the various breaks of gauge, Australian railways provide some excellent services, in many respects the expresses of New South Wales and Victoria compare favourably with the best trains in any part of the world.

The transport of the State of New South Wales is controlled by a Commission including representatives of roads, road transport, tramways and railways. The railways of the State, which total, in 1935, more than 6,100 miles of standard-gauge lines, constitute the largest industrial undertaking in Australia. The Southern line extends to the Victorian border, and branches serve the world-famous Riverina district, as well as Canberra, the federal capital. The Western line climbs over the Blue Mountains, where the track rises to 3,500 ft. There are health and pleasure resorts in the mountains; the Jenolan Caves are famous. The line then descends to the western plateau. The most distant terminal is at Broken Hill, 698 miles due west of Sydney. It there links up with broad gauge lines running through South Australia to Adelaide. The Northern Line, soon after leaving Sydney, crosses the Hawkesbury River by a bridge 2,900 ft. long, which, before the construction of Sydney Bridge, was the pride of New South Wales. From the opening of the railways in 1855 until the erection of the bridge in 1889, the line from Sydney to Newcastle, a port a hundred miles north of the capital and the second city of the State, was divided by the river. The North Coast Line is part of a shorter route between Sydney and Brisbane. The line across the border has been made on the standard gauge as far as Brisbane (the Queensland gauge is 3 ft. 6 in.), so permitting through running between Sydney and Brisbane. The South Coast Line is famous for its scenery. Owing to the mountains of the Great Dividing Range which for so long isolated the earlier settlers, confining them to the narrow coastal strip, most of the traffic has to be hauled over difficult country. Engineers are constantly at work regrading the line to expedite traffic and reduce costs. At one time the railways imported locomotives and rolling-stock from Great Britain and the United States, but practically all requirements have for many years been met locally. Steep gradients and sharp curves are unavoidable on many sections in the mountainous regions. In the southern system the station at Roslyn, near Crookwell, is at an altitude of 3,225 ft.; at Nimmitabel, on the Goulburn to Bombala Railway, the height is 3,503 ft. On the western system the height is 3,503 ft. at Newnes Junction, in the Blue Mountains, and 3,623 ft. at Oberon, the terminus of a branch line. On the northern system, Ben Lomond Station stands 4,473 ft. above the sea. The standard rails are 100 lb. per yard in the metropolitan area, 80 to 90 lb. on main lines, and 60 lb. on branch lines. Australian hardwood sleepers, 8 ft. by 9 in. by 4½ in., are laid at the rate of eighteen per 40 ft. of rail along the permanent way. The most important inter-state expresses are the Sydney-Melbourne Limited and its counterpart, the Melbourne-Sydney Limited, connecting the capitals of New South Wales and Victoria. Since the Victorian gauge is 5 ft. 3 in., through working is impossible, and passengers have to change at Albury, 401 miles from Sydney. The total distance of 592 miles is covered in 16 hours 20 minutes the return journey takes five minutes more. In view of the difficulties of the route the average speed of thirty-six miles an hour is excellent. The Limited takes sleeping-car passengers only, and a supplementary charge is made.

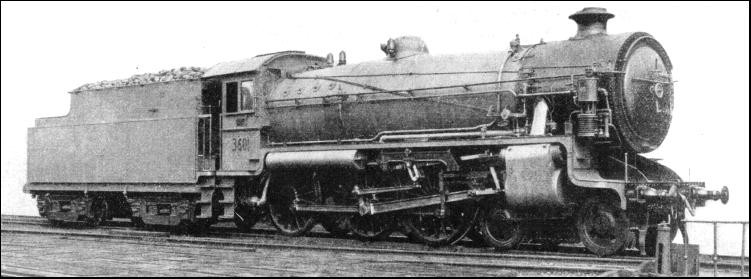

A popular train operating within the borders of the State is the "South Coast Daylight Express," which runs between Sydney and Nowra, ninety-five miles, in just over three hours. It is made up of six coaches, painted green and cream, with the name of the express in gold letters on the leading car. The coaches are of the centre-corridor type. with seats for seventy-two first- and 140 second-class passengers. The locomotives are of the "C 35" class, with 22½ by 26 in. cylinders, 5 ft. 9 in. driving-wheels, and 180 lb. boiler pressure; they weigh 124 tons, with tender, in running trim. Another famous train, the "Caves Express" is normally made up of five light cars, the total weight being just over a hundred tons. The speed for the first fourteen miles through the suburbs of Sydney, with 1 in 90 grades, averages forty-two miles an hour. The next section of twenty miles is run in twenty-two minutes over give-and-take 1 in 80 grades, the average speed for the thirty-four miles being forty-eight and a half miles an hour. After two level miles the "Caves Express" covers ten and a half miles continuously at 1 in 60, which is taken at thirty-six miles an hour. The grades then stiffen, half the line for the next twenty miles being 1 in 33, the total lift being 2,280 ft. The last ten miles reduce the speed of the express to twenty-four miles an hour. She makes her first stop fifty-eight miles front Sydney at an elevation of 2,220 ft. The remaining portions of the trip average twenty-two to twenty-four miles an hour between stations over gradients again as 1 in 33. New South Wales passenger traffic is divided into suburban and country sections, the former being that within thirty-four miles of the cities of Sydney and Newcastle. Most of the country trains leave Sydney in the evening to fit in with postal needs and, therefore, do not carry dining cars. They arrive at the termini in the country, several hundred miles from Sydney, with the mails and passengers, in the morning. In the four hours between 6.45 and 10.45 p.m. about fifteen expresses and mail trains leave Sydney Central Station. In the morning about a dozen arrive between, approximately, five and seven o’clock Another five pull into Sydney before noon. The State has a safety record in which it takes pride. In one period of twenty years there were fourteen years during which there were no fatal accidents on the railways. In the remaining six years fifty-two passengers were killed, but by causes beyond the control of the Railways Department - a noteworthy record for a railway operating some six thousand miles of lines through all sorts of country. In 1935 the State owned 6,164 miles of track, 1,287 locomotives, 2,673 carriages, 37 motor passenger vehicles, 22,247 freight wagons and 1,458 service wagons. Among the largest locomotives is the three-cylinder 4-8-2 "Mountain" type of the "D 57" class.

Rail motor transport on branch lines began in 1919 with a converted motor lorry, the railways now have nearly forty rail-cars. The normal type, with double-ended control, has a length of 41 ft. 10 in. over body, and seats twenty-one first-class and twenty- four second-class passengers. The motor is a six-cylinder ninety-five horse-power unit. The car is capable of a speed of forty-five miles an hour. The suburban lines round Sydney have been electrified on the multiple-unit system, and equipped with automatic signalling. The City Underground Railway is also electrically operated. Sydney Harbour Bridge, the largest single-arch span bridge yet constructed, as of 1935, is one of the world’s greatest engineering feats. As the traveller enters Sydney from the sea it dominates the scene so overwhelmingly that when the visitor is asked the old question that is always asked in Sydney, "What do you think of our harbour ?" he begins talking about the bridge. The graceful beauty of the structure is a delight to the eye. Sydney, with a population of over 1,240,000, was the third largest city in the British Empire. It lies mainly on the southern side of the harbour but at an early period suburbs began to grow on the northern side until, before the bridge was built, as many as 100,000 persons were carried by ferry steamers into the city in the morning and back in the evening.

The building of the bridge had to be carried out without hindering shipping, for the big liners, up to 20,000 tons, pass under the bridge to their berths; more than half the shipping of Sydney, the chief port in Australia, goes under it. Hence the width of the central span of 1,650 ft., and the height giving head-room of 170 ft. at low water. The top of the arch is 445 ft. above the water. The total length of the bridge is 3,770 ft., and its width 160 ft. There are five steel approach spans at either end of the main arch. The arch contains 37,000 tons of steel. In all, the bridge contains 52,300 tons of steel work. It has provision for traffic which comprises four lines of electrical railway, a roadway for six lines of vehicles, and two footpaths both 10 ft. wide. The maximum hourly capacity is 128 electric trains, 6,000 vehicles in each direction, and 40,000 pedestrians. Including the approaches, the total length of the bridge is two miles and three-quarters. Construction and other costs were about £10,000,000, the actual construction cost being about £6,250,000. The first sod was turned on July 28, 1923, and the official opening was on March 19, 1932. Before the official opening, locomotives and tenders were run on to all four tracks until they stood end to end extending across the main arch. After this, locomotives were placed on all four tracks over one-half the arch only. Careful readings of the stresses under the various tests were made. The bridge successfully passed its examination. There is a striking contrast between the splendour of this monument of skill and enterprise and the painfully slow progress of the early railway pioneers. Sydney is hemmed in by mountains, and the State was not wealthy enough to borrow large sums at that time. Thus it took six years (1862-8) to build the railway on the Western Line from Penrith to Mount Victoria, forty-two miles, and eight years more to take it a further sixty-nine miles to Bathurst.

From the opening of the railways in 1855 to 1864 only 143 miles of lines were built the next decade to 1874 added only 260 miles. Progress accelerated, and 1,215 miles were added before the end of 1884 The rate dropped again to the year 1894 to 883 miles and to 780 miles in the decade ending 1904. Also a further drop in the rate of mileage additions continued to 1914, but between then and 1924 came an increase of 1,556 miles. Since that time steady progress has been made. The present tendency is towards more powerful locomotives for heavy traffic and rail-cars for branch-line passenger traffic. The locomotives are fired with New South Wales coal, and it is hoped that in the future the internal combustion engines of the rail-cars will be propelled by fuel distilled from brown coal. Victoria is remarkably well served by railways. Hardly any appreciable area of arable, pastoral, or non-mountainous land in the State is more than ten miles from a railway. The railway policy has been to regard the iron roads as wealth creators rather than profit makers. An illustration of the effect of this policy is provided by Mallee, in the north-west of the State. It has an area of over 11,000,000 acres, which, until the "eighties," was regarded as worthless, and was shut off by a high, vermin-proof fence. Now, thanks to railways and a wonderful water supply system, it is dotted in every direction by settlements, farms, and towns.

The State uses the railways to send knowledge to the farming communities instead of expecting those communities to go to the cities. With this object the two Departments of Agriculture and Railways co-operated and produced an agricultural college on wheels to demonstrate to the man on the land the lessons taught by research and experience. Not only was the man thought of but also his wife. There are cookery and domestic science experts on the "Better Farming" train, as it is called. Women experienced in welfare work, the care of children, nursing and needle-craft, and all aspects of home life travel in the lecture car, which can accommodate an audience of eighty. A typical "Better Farming" train which went on a ten-day tour of Gippsland, in the south-cast of Victoria, consisted of fifteen cars and trucks all of which had been painted a bright yellow. There was accommodation for the staff and visitors, a section for the women demonstrators, and a car carrying an electric light plant (the space remaining was utilised for carrying fodder for the pure-bred stock on the train). There was also a car with models of farms, another showing dairy utensils, and a section devoted to honey, a tobacco and a potato car; a vehicle devoted to the prevention and study of diseases of animals, a wool exhibition, a vehicle containing specimens of soil and grasses, intended to demonstrate the value of top dressings and artificial fertilisers, and three cars carrying livestock. "Reso," or National Resources Development Trains, go on tour to give city men a knowledge of the State’s resources. These trains are self-contained, and include a staff car with typists. An average charge is fifteen guineas for a trip of seven days. Land cruises are a feature of the holiday season. One cruising train took fifty-nine tourists for a "cruise" of 383 miles by rail, and provided motor-car excursions covering 180 miles. There were two lounge coaches, "Norman" and "Goulburn." "Nornian" is a twelve-wheel observation car used by the Victoria Railway Commissioners, and has a speedometer, height recorder, barometer, wireless and roll-up maps, so that the tourists of a statistical turn of mind could thoroughly satiate their thirst for knowledge. After Melbourne, Geelong is the chief coastal city in the State, The "Geelong Flyer" is Victoria’s crack express. The distance is forty-five miles, and the "Geelong Flyer" runs non-stop in sixty minutes, speed not normally being allowed to exceed sixty miles an hour. The train goes on to Port Fairy, which is 187 miles from Melbourne. Beyond Geelong it passes through three tunnels and rises in nine miles to 333 ft. at Pettavel Road after several steep stretches of 1 in 50. There is a gradual ascent to Buckley, after which the line falls again and crosses the Barwon River, just outside Winchelsea. The journey to Port Fairy takes seven hours.

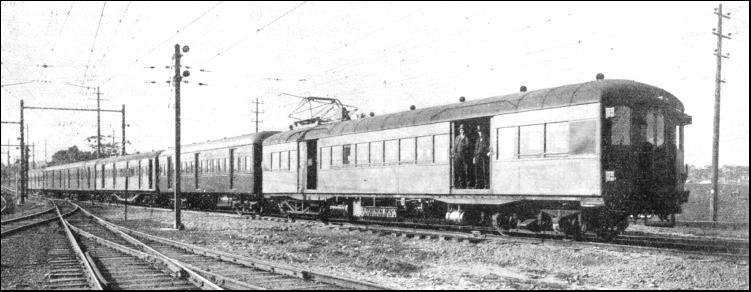

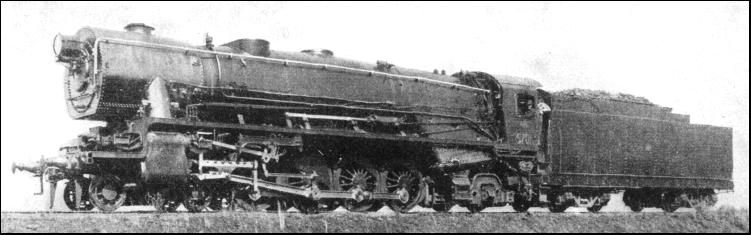

For the Melbourne-Sydney Limited Expresses three-cylinder locomotives of the "Pacific" type are used. The time allowed for the 191 miles from Melbourne to Albury, including one intermediate stop for refreshments, is four and a half hours. From eight to twelve cars are hauled by three-cylinder locomotives of the "S.300" 4-6-2 type. There is an all-steel dining-car, and the rear car is an observation car which carries the name of the express, illuminated at night, round the railing of the rear platform. The State Railway system comprises about 4,600 miles of 5 ft. 3 in. gauge track, over 173 miles of which are electrified. And there was, in 1935, 638 steam and twelve electric locomotives, 1,598 steam and 856 electric coaches, thirty-three electric trains, ninety-eight rail motor vehicles, 20,129 goods vehicles, and 794 service vehicles. The workshops are at Newport. Flinders Street Station, Melbourne, has at times been claimed, without complete justification, to have the heaviest passenger traffic in the world. It is certainly a busy spot, with its sixteen passenger platforms in constant use, especially on Melbourne Cup day. The race for the Melbourne Cup, at Flemington Race-course, is, perhaps, the principal sporting event in the Southern Hemisphere. There is a nursery in the station which in one year cared for nearly 9,000 children. Melbourne and Sydney are two of the most attractive cities in the world. To the visitor from the Old World they each convey a message of beauty and endeavour. Cleaner and, in many ways, more progressive than many European cities, which are rooted in the past, each represents a triumph of Anglo-Saxon organisation, especially when it is remembered that it is not long (rather more than a century ago with Melbourne) when the sites of both cities were merely unclaimed wilderness. The railways have, of course, played their part in the development of the two cities. Going westward into South Australia the traveller finds the sunlit city of Adelaide. For size, Adelaide cannot compare with her sisters, but she has a charm of her own. The railway station is one of the finest in the Commonwealth. The State operates about 1,450 miles of 5 ft. 3 in. gauge lines, and nearly 1,100 miles of 3 ft. 6 in. gauge. Figures for the broad gauge rolling-stock are 250 locomotives, 497 carriages, and 3,567 wagons; narrow gauge: 188 locomotives, 201 carriages and 5,628 wagons. The well-equipped locomotive workshops at Islington have turned out some very powerful locomotives. The standard gauge line, part of the Trans-Australian Railway, and the narrow gauge Central Australia Railway (Port Augusta to Alice Springs) are owned by the Commonwealth Government Railways. Alice Springs is the present railhead of the projected North-South Transcontinental Railway, which may one day link Adelaide with Darwin, the Australian settlement so well known to long-distance flyers. The principal train is the Adelaide-Melbourne Express (broad gauge). Until recent years Melbourne and Adelaide were the only two State capitals connected by lines of the same gauge. The express has stock belonging jointly to South Australia and to Victoria, with first and second-class compartments, and sleeping and day coaches. It is hauled by locomotives of the "Mountain" type, "500" class. "Mikado" type locomotives are used for goods traffic.

The South Australian railway system has been reorganised in recent years. Before reorganisation some veteran locomotives were in use. On the broad gauge lines a Disabilities Commission found a locomotive sixty-five years old, another aged sixty-three, a third aged sixty, two aged fifty, and a considerable number in the forties. What shocked the Commission more was the fact that these veterans were shown in the accounts at full capital value, nothing having been allowed for depreciation even after as long as sixty-five years wear and tear. Matters have altered since then. Not only has a policy of running new and powerful locomotives been adopted, but, in the Mount Lofty Ranges, steep gradients and acute curves have also been reduced and freight trains in this district now load up to nearly 600 tons as compared with ninety-five tons in the year 1883. Petrol rail-cars are used to augment passenger services. They are of two types, 66 and 186 horse-power, and in general operation usually consist of the car with one or more trailers. Three hundred miles a day is an ordinary performance for many of these cars. The State has specialised in freight cars. A weatherproof thirty-ton box car is extensively used for handling merchandise in small consignments between terminals. The box car renders tarpaulins unnecessary, and there is no delay in sheeting and un-sheeting, while loading and unloading are expedited. The "Poison Train" is interesting. Weeds and other vegetation growing in the ballast and alongside the track are destroyed by an arsenical compound solution sprayed on to the permanent way by travelling tanks. The total capacity of the tanks which form the "Poison Train" is 13,500 gallons, or sufficient for ten miles of track. The tracks are poisoned every third year, or more often if weed growth interferes with ballast drainage, or the weeds grow over the rails and cause the wheels of engines to slip. Formerly, trolleys were sent out which, with a capacity of 400 gallons of weed-killer, could handle only a quarter of a mile of track at a time; modern methods deal with ten miles of track in one operation. Other vehicles made in South Australia include a refrigerator milk car (capacity 8,000 gallons), a sheep car (capacity 120 sheep), a cattle car (capacity eighteen cattle), glass-lined refrigerator milk vans (capacity 2,400 gallons), and cheese containers or flat cars carrying 2,500 cheeses. Cattle trains of ninety-four cars, net tonnage of 500 tons of mallee roots, 240 net tons of firewood, 1,349 tons of wayside freight, eight cars containing 5,500 bags of wheat - such are the loads locomotives have to haul. The cost of hauling water for locomotive purposes in one year was nearly £100,000. Before the "Mountain" type locomotive was built to haul passengers and freight trains over the Mount Lofty Ranges, where the ruling grade is 1 in 37, with ten chains curvature, the Melbourne Express, with a load of 375 tons, was hauled by three "Rx" engines (two hauling and one pushing) to the summit. Nowadays one "Mountain" type locomotive can take 430 tons. This feat is accomplished unaided. The "Pacific" locomotive is a powerful passenger engine capable of high speeds if required, and is used for hauling fast heavy passenger trains (Trans-Continental and Broken Hill Expresses) on the main northern line, and the Melbourne Express between the River Murray and the Victorian Border on the main southern line, the "Pacific" can haul twice the load which the "S" engine, previously used, could manage. Some "Mountain" locomotives are equipped with a "booster." The "booster," the low-power gear necessary to assist an engine in starting heavy trains, and when negotiating stiff gradients, is supplied by a simple two-cylinder steam engine fitted to the trailer truck of the locomotive. It turns trailing wheels into driving wheels and increases the schedule load from eighteen to twenty-five per cent. The maximum efficiency of the unit is obtained when the speed of the train is below twelve miles an hour. The schedule freight load for a "Mountain" locomotive up the 1 in 37 grades through the Mount Lofty Ranges has been increased from 500 to 570 tons. Mechanical stoking is used on some of the larger locomotives. The coal is crushed in the tender to the requisite size, brought forward by worm drive, and later spread fan wise over the grate area by steam pressure. The even distribution ensures economy in coal consumption and an increase in engine efficiency.

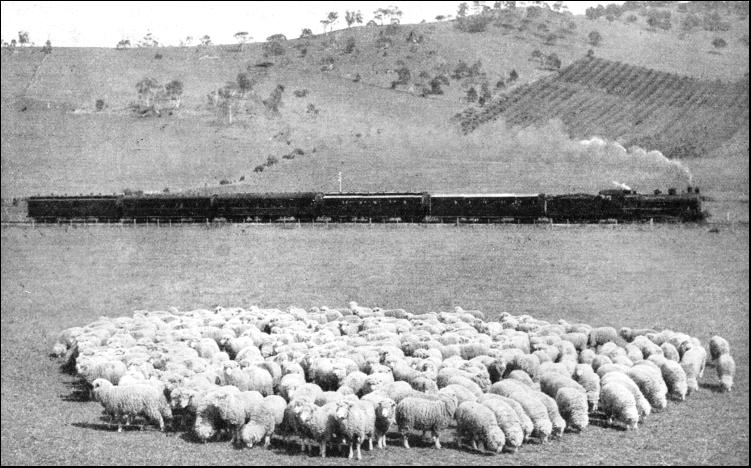

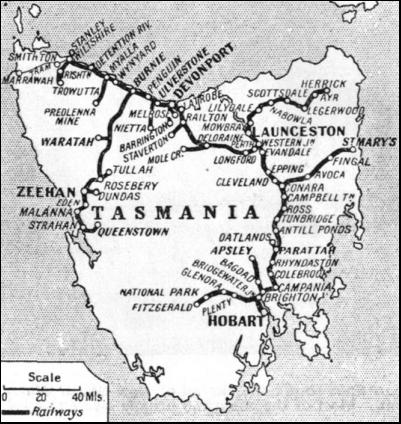

Beautiful mountain scenery, steep gradients, and sharp curves are features of the railways of Tasmania, the island State of the Australian Commonwealth. Tasmania is called "The Playground of Australia,” and attracts holiday-makers and sportsmen. The railway gauge is 3 ft. 6 in., except for a short stretch of 2 ft. gauge. The first railway was opened in 1871 between Launceston, in the north of the island, and Deloraine, to the west, and was forty-five miles in length. The line was owned by the Launceston and Western Railway Company, which soon experienced financial difficulties, and the Government acquired the railway in 1873. The main line between Hobart, the capital, and Launceston was also built by a company which operated it until 1890, when it was purchased by the Government. Extensions of the Western Line and the construction of branch lines were carried out, and the total mileage of Government railways is now 645; 634 miles of 3 ft. 6 in. gauge; 11 of 2 ft. gauge. The Emu Bay Railway Company owns 104 miles, and the Mount Lyell Company twenty-one and a half miles. Owing to the mountainous interior and the number of ports, particularly on the Northern Coast Line, and also the number of good roads, the railways have had to face severe competition by sea and road transport. Recently the passenger traffic problem has been partly solved by the introduction of rail-cars. Experiments were made with petrol-driven cars, but steam-driven cars proved more suitable. These are now used not only for regular passenger services but also for special trips at ordinary times. Personally conducted parties are arranged to tour the greater part of the island, places not on the railway being reached by motor-car. The first two "Sentinel-Cammell" rail-cars supplied in 1931 were of 100-150 h.p., fitted with a vertical water-tube boiler at one end of the car, and a six-cylinder engine driving on to one pair of wheels of the forward bogie through a cardan shaft and a gear-box mounted on the axle. These cars were 58 ft. long, and weighed, fully loaded, about thirty-five tons. They had seating accommodation for eighteen first and twenty-one second class passengers. A larger type now in service is of 250-300 h.p. The power unit consists of a three-drum water-tube boiler placed at one end of the car. This supplies steam to twin-cylinder engines suspended under the frame. Each engine drives one pair of wheels of each bogie. These larger cars are sixty-four feet long and weigh, fully loaded, about fifty-two tons. The seating accommodation is about the same as the smaller type, but these cars are able to negotiate the heavy gradients at higher speeds. A driving compartment at either end enables the car to he driven in both directions. When a liner calls at Hobart, a rail-car or a train, according to the number of passengers, is waiting at the quay to take passengers to the Derwent Valley and the National Park. The line follows the banks of the River Derwent for nearly forty miles, crossing and recrossing the river several times. Orchards and hop gardens are on either sidle. In springtime, when tile fruit trees are blossoming and the river banks are fringed with wattles and blackwoods, the scene is a blaze of colour. Autumn is lovely also with the splendour of the hop gardens, with apple trees thrusting red and yellow arms almost into the carriage windows, and with the poplars and willows reflected in the clear waters of the placid Derwent. The train halts at the gates of the 40,000 acres National Park, with the Russell Falls, which are 120 ft. high, near by. The main line is 133 miles in length and connects the cities of Hobart and Launceston, the greatest altitude being 1,500 ft. The boat express covers the distance in about five hours and a quarter. For the first twelve miles the railway runs alongside the River Derwent, crossing the river at Bridgewater over a long causeway and bridge. Farming country is traversed through hills and valleys, with a tunnel forty-five miles from Hobart. The train goes on through the "Midlands" sheep-raising country, and then takes a course midway between the Western Tiers and the Ben Lomond Range, crossing the rivers Macquarie and South Esk. The approach to Launceston through the White Hills farming district is very attractive.

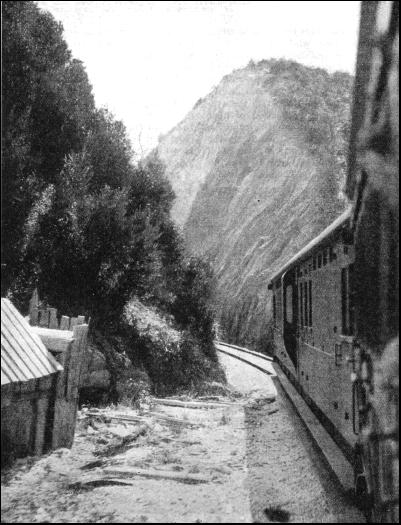

Launceston claims the honour of founding the State of Victoria. In 1834 two members of the Henty family left Launccston, then a village, crossed Bass Strait and occupied a portion of Portland Bay area with flocks of sheep. It was also from Launceston that John Batman sailed on May 12, 1835, for Victoria, and a month later steered a boat up the River Yarra and exclaimed, "This will be the place for a village" when he contemplated the site of Melbourne, Batman’s vessel was a thirty-ton schooner, "Rebecca." Batman was one of a syndicate of fifteen Launceston men who found the money to fit her out. The Fingal Line is a branch of forty-seven miles, leaving the main line at Conara Junction, running though fairly level country under the foothills of the Ben Lomond Range and following for a while the valley of the beautiful South Esk River. The line ends in a coal-mining area at St. Mary’s Station, from which a motor-car service connects with the North-Eastern Line at Herrick. The North Eastern Line extends eighty-five miles from Launceston, through forests and along hillsides to serve agricultural, dairying, timber, and mining areas. There is a large apple and pear orchard at Lilydale Station, and this and the Blidestowe Lavender Estate attract tourists. The line goes on through the town of Scottsdale and ends at Herrick. The Western Line runs from Launceston for 168 miles to Stanley, serving the principal agricultural area of Tasmania. It crosses a number of rivers and touches a score of towns, and reveals farming areas that are a delight to sightseers. Some of the towns passed in the first forty-five miles are particularly English in appearance, having rivers running through them, and streets planted with oaks and pines. A branch line runs off at Lemana to the Mole Creek Caves area, which is famous for its scenery. After crossing the River Mersey the line reaches the coast and runs within sight of the sea for about fifty miles, traversing an area of rich agricultural land between the mountains and the sea. Several short branch lines strike inland to serve farm, timber, and mineral areas. The Emu Bay Company’s Line runs from Burnie, on the north-west coast, southwards to Zeehan, for eighty-eight miles. From Zeehan a Government line of thirty miles links it with the port of Strahan, and bridges the gap between the Emu Bay Company’s Line and the Mount Lyell Line. From Burnie the railway climbs steadily, affording backward glimpses of the sea over a foreground of farms. Then the line plunges into the forests, and winds round mountain ranges crossing the Pieman River over a high bridge, the view of the Murchison Range from near Rosebery being especially fine. From Guildford Junction a branch line runs to the town of Waratah, the home of the Mount Bischoff Tin Mine. Another branch line runs off from Farrell to Tullah, a mining town in a picturesque setting among the mountains. Zeehan, the terminus, was once a rich silver-mining town, but its prosperity has declined. The Mount Lyell Mining Company’s Line, over twenty miles long, runs from the port of Strahan to Queenstown, where the mine known as Mount Lyell is situated. This mine produces copper, silver, and gold. The line is remarkable for the views its affords, as it follows the gorges of the Great King River, giving vistas of awesome canyons and magnificent forests of beech trees, with grass-trees, ferns, berries and wild flowers in profusion. Queenstown is hemmed in by mountains. Haulage lines in connection with the great mine run up the faces of mountains, giving wonderful panoramas. Although these private railways are little known, they are relatively of considerable importance. The Emu Bay Company’s Line, for instance, has 104 miles of track open, owning some dozen locomotives, and it is worth remembering that from such small lines the worlds railways grew up

Many thanks for your help

|

Share this page on Facebook - Share  [email protected] |