|

|

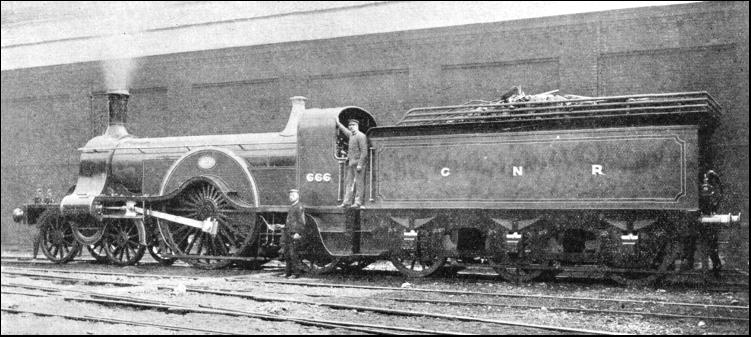

There are many strange ideas abroad as to what the steam locomotive has done and can do in the way of speed. From early railway days many "records" have been claimed for steam locomotives which prove, on examination, to have no foundation in fact. The most accurate of apparatus, handled by the most competent observers, is used to establish record speeds in the air or on the motor-racing track; and without some such corroboration many so-called railway records must be dismissed, however regretfully, as lacking proper authentication; others are so clearly impossible as to be no more than myths. Fortunately, however, the railway records which have been made in recent years are fully authenticated, and may be accepted without reserve. British appetite for high speed was first whetted, probably, by the famous "races" to Scotland which took place in 1888 and 1895. Competition in those days was keen between the West Coast and the East Coast companies for the traffic between London and Scotland. The 1888 race to Edinburgh was precipitated by the fact that the Great Northern, North Eastern, and North British Railways, forming the East Coast route, decided to admit third-class passengers to the "Flying Scotsman," whereas up till then the principal trains by both routes bad been first and second class only. The race of 1895 was far the more exciting of the two - was to Aberdeen, and followed on the accelerations which the opening of the Forth and Tay Bridges had made possible on the East Coast route. The culmination of the 1895 race occurred during the month of August The two trains concerned were the night expresses leaving Euston and King’s Cross at eight o’clock. Provisional time-table had followed provisional time-table, each quicker than the last, until finally time-tables were dispensed with altogether, and the trains left to make the best time they could. A piquant feature of the contest was that the East Coast flyer had to use West Coast metals for the last 38 miles of the journey, from Kinnaber Junction, near Montrose, to its goal at Aberdeen. Finally, on August 20, the East Coast express, drawn by Patrick Stirling’s famous "8-footers" from King’s Cross to York, and from there to Edinburgh by North Eastern 4-4-0's Nos. 1620 and 1621 - engines were changed at Grantham, York, and Newcastle - reached Edinburgh in 6 hours 19 minutes from London ( in 1935, a time which had not been equalled ), and Aberdeen, 523¼ miles from London, in 8 hours 40 minutes. This worked out at just over sixty miles an hour for the whole distance, notwithstanding the extremely difficult section of the route between Edinburgh and Aberdeen. Determined not to be outdone, the London and North Western and the Caledonian Railways, which together formed the West Coast route, put forth their supreme effort on the following night, and brought the Granite City within 8 hours 42 minutes of London over a route nearly seventeen miles longer. A Webb compound engine hauled the train from Euston to Crewe from there the noted 2-4-0 locomotive "Hardwicke" took the train over the 141 miles to Carlisle - Shap Summit included, with its 915 ft. of altitude - in 120 minutes; at Carlisle a Caledonian locomotive took charge; and a further change of engine was made at Perth.

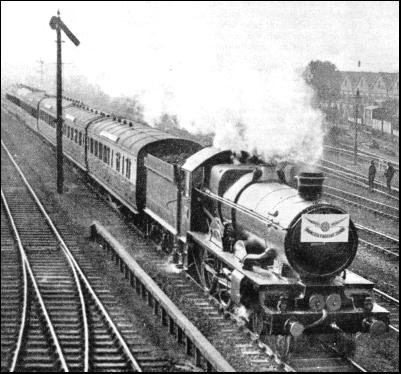

Thus an average of 63.3 miles an hour, including three stops and both Shap and Beattock summits (the latter 1,015 ft. above the sea), was maintained over the whole distance of 540 miles. But the train was a very light one of three coaches only, weighing seventy tons, while the East Coast train was but little over 100 tons in weight, corresponding to only two or three corridor coaches respectively of modern British stock. The next similar contests took place in 1903 and 1904. when certain of the Transatlantic shipping companies, the American Line in particular, began the practice of making a call on the east-bound voyage at Plymouth. Rivalry broke not between the Great Western and London and South Western Companies as to which of them could make the fastest journeys from Plymouth to London, the former with the mails and the latter with the passengers. It was on May 9. 1904, that the most startling speed achievement was staged, and the Great Western Railway was responsible. The Westbury route had not then been brought into use, so that the journey was over the original route of 245¾ miles, via Bristol, where a stop of 3¾ minutes was made to detach the mails for the North of England. Notwithstanding the exceptionally heavy gradients west of Newton Abbot, the whole journey was completed in 3 hours 46¾ minutes. It was on this occasion that the engine, "City of Truro," is claimed to have touched 102.3 miles an hour in the descent of Wellington bank, near Taunton; the 118½ miles from Bristol to Paddington were run by the old Dean single-driver locomotive, "Duke of Connaught" which maintained an average speed of 80 miles an hour for 74½ miles on end, in 99¾ minutes. Nearly thirty years then elapsed before any further record-breaking of note was attempted. On June 6, 1932, however, the Great Western Railway established a record which still stands supreme. It was a run from Swindon to Paddington, with the "Cheltenham Flyer," in which the 77.3 miles from Swindon to Paddington were covered from start to stop in 56 minutes 47 seconds, at an average speed of 81.68 miles an hour. No other steam train has ever run from start to stop at over 80 miles an hour either before or since. And until 1935 no Diesel-driven train had ever done so either. "Tregenna Castle" was the engine, with a six-coach train, weighing with passengers and luggage, 195 tons. For 70 miles continuously the amazing average speed of 87.5 miles an hour was maintained; for 28 miles of level track speed was 90 miles an hour or over; and the maximum attained was 92.3 miles an hour. Not content with this the Great Western Railway then took the recorders of the times straight back to Swindon on the 5 pm express, with "Manorbier Castle" and a 210-ton train, in one second over the even hour - covering 77.3 miles against the rising tendency of the road ( for Swindon lies 270 ft. higher than Paddington ), and, last of all, stopped the 5.15 pm express from Bristol at Swindon specially to pick them up and return them to London, which was done in 66½ minutes more. Thus the recorders of the times made three journeys over this 77¼-mile course between the limits of 3.50 and 7.12½ pm, covering a total of 220 miles out of 231¾ miles at an average of 80 miles an hour.

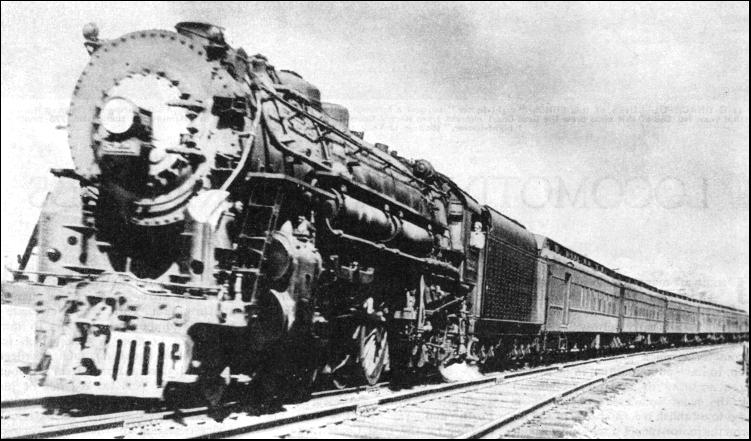

Next, the London, Midland and Scottish Railway comes into the field, with a remarkable series of runs made on two consecutive days, September, 19 and 20, 1933, between Euston and Coventry. These trains were chartered by a motor firm to convey parties to and from their Coventry works, and the railway authorities determined that they should have a demonstration of railway speed possibilities at the same time. The engines participating were of the 3-cylinder 4-6-0 "Royal Scot" type; "Comet" gave the most distinguished performance On the first day "Comet" ran from Coventry to a signal stop just outside Euston, a distance of 93½ miles, in 74 minutes 20 seconds, inclusive of several checks; four times in succession it reached or exceeded 90 miles an hour; the absolute maximum was 92. On the two consecutive days this one engine, in four trips, with an average load of 275 tons and over an undulating road, covered a total of 235 miles at an average speed of 79.1 miles an hour. Another important speed trial was made on April 6, 1934, when the L.M.S. "Pacific" engine "The Princess Royal" was attached to the 5.25 pm express from Liverpool to Euston, and made the run of 152.7 miles from Crewe to Willesden Junction in 134 minutes 37 seconds. The feature of this journey was that. although the maximum speed did not exceed 85 miles an hour, the engine maintained an average of 70.5 miles an hour, with a heavy twelve-coach train weighing 380 tons all found, for 140 miles continuously, inclusive of the usual slowings through Stafford and Rugby. Meanwhile the Americans had not been idle. One of the fastest railway runs in the history of American railways was made in 1905 by the express service of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad. For many years this service was booked to make the run of 55½ miles from Camden to Atlantic City in 55 minutes - at that time the fastest booked run in the world. In order to recover late starts - caused by the late arrival of the ferry from Philadelphia at Camden - runs in less than schedule time were common. The fastest of these ever known was in May, 1905, when the journey was completed in 42 minutes 33 seconds, at an average start-to-stop speed of 78.3 miles an hour. This run held the world’s start-to-stop record until the Great Western Railway took the lead, in June, 1932, with the record of 81.68 miles an hour from Swindon to Paddington. The next American achievement of note was the the return of Colonel Lindbergh from his historic solo flight across the Atlantic in 1927. It was desired to get the films of his reception at Washington, on his arrival home, to New York in the minimum possible time, and a special was therefore chartered over the Pennsylvania lines. With two coaches only, the run of 224½ miles from Washington to New York was completed in 3 hours 4 minutes, notwithstanding the fact that two stops were made on the way. Four stretches of line, 38, 61, 23, and 66½ miles in length successively, were covered at an average of 80 miles an hour or over; the 66½-mile section, from Holmesburg Junction to Newark, New Jersey, was covered at an average of 85 miles an hour. Since then a competition in schedules has been developing between the railways which compete for the traffic between Chicago, Milwaukee, and the "Twin Cities" of St. Paul and Minneapolis. Diesel-driven high-speed trains have been built but the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad determined to give a demonstration of the exploits of which steam is still capable. In the summer of 1934, therefore, a five-coach train of heavy American stock was made up, weighing with passengers and luggage about 380 tons, and drawn by a large and powerful 4-6-4 locomotive, No. 6,402, with the intention of making the fastest possible time from Chicago to Milwaukee.

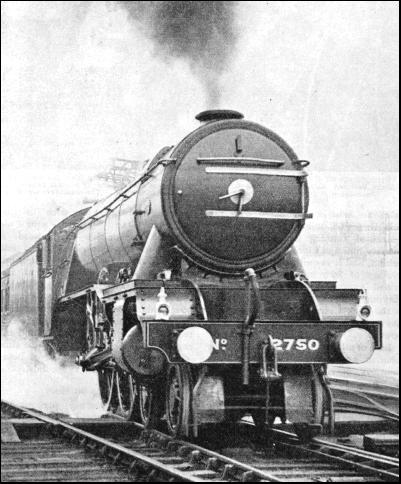

Although the Americans may have claimed to have beaten the Great Western Railway Swindon - Paddington record on this trip, they did not succeed in doing so on a start-to-stop basis, as their time for the 85 miles from Chicago to Milwaukee - 67 minutes 35 seconds - gives a start-to-stop speed of 75.5 miles an hour, as compared with the G.W.R.'s 81.68 miles an hour. But restrained running is necessary until the city limits of Chicago have been left behind, and it is quite possible that the average of 89.9 miles an hour maintained over the 68.7 miles between Mayfair, Illinois, and Lake Wisconsin is the fastest stretch of its length that has ever yet been accomplished by steam power. Last of all, there came the remarkable London and North Eastern Railway journeys of November 30, 1934, and March 5, 1935. These were deliberately arranged as the challenge of steam to Diesel propulsion which is being pressed on British railways, following on the successful running of the "Flying Hamburger" rail-car in Germany, as the best method of working high-speed services, but the L.N.E.R. claim that they can do equally well with steam, generated from Britain’s own native fuel - coal - and set out to prove it. For the Leeds run, on November 30, 1934, a four-coach train was made up, weighing 145 tons, with "Flying Scotsman" - an eleven-year-old "Pacific" locomotive - at the head. A provisional schedule of 2¾ hours had been laid down for the 185.8 miles, but this was found easily capable of improvement. The run was made in thirteen minutes less - 151 minutes 56 seconds, to be precise. For the return journey two more coaches were added, making a total of 208 tons behind the engine tender, but once again the time was improved on, King’s Cross being reached in 157 minutes 17 seconds. Of the round journey, perhaps the most amazing feature was that the engine climbed the whole of the last ten miles to Stoke Summit, partly at 1 in 200 and partly at 1 in 178, at an average of 82.5 miles an hour, and went over the top at 81 miles an hour. Down the same bank, in the reverse direction, a maximum of 100 miles an hour was reached. Of the return journey, all made by the one locomotive, no fewer than 250 miles in all were covered at the high average speed of 80 miles an hour. But these figures were eclipsed by those of March 5, 1935. King’s Cross - Newcastle was the course on the latter occasion, and No. 2750 "Papyrus" - a seven-year-old "Pacific" of the high-pressure series - was the engine. The test was devised to show the practicability of working a train of six coaches, weighing 217 tons, over the 268.3 miles between King’s Cross and Newcastle in four hours each way. Notwithstanding the fact that again the same engine was used in both directions, and that 11½ minutes were lost in consequence of some wagons being off the road at Arksey, the task was performed with triumphant case, and with eleven more minutes to spare. Sheaves of records were amassed on this amazing day. Allowing for the Arksey delays "Papyrus" did the round trip of 536.6 miles at an hour average of 70.4 miles an hour, and covered 500 miles at 72.7 miles an hour; 300 miles exactly out of the total distance covered were reeled off at 80 miles an hour and the climax, in the descent from Stoke Summit to Peterborough, was the feat of covering 12.3 miles at 100.6 miles an hour average, with a fully authenticated maximum of 108 miles an hour. Every one of these achievements. so far as is known, was a world’s record for steam traction. So far from this trip having been merely a speed "stunt," the lessons learned were of such value that it was decided to institute in October 1935, a daily four-hour service between King’s Cross and Newcastle, with specially built trains, each seating 194 passengers, and equipped within restaurant cars, fully streamlined throughout. From such records as these, it is clear that steam has still plenty of fight left. This multiplication of records suggests that even the wonderful runs described here may be improved upon in the near future. Both in this country and abroad considerable attention has been given to streamlining. As a footnote, L.N.E.R. class A4, "Mallard" attained a speed of 126 miles an hour, on the descent from Stoke Summit in 1938, a world record for a steam locomotive, which is held to this day.........

Many thanks for your help

|

Share this page on Facebook - Share  [email protected] |