|

|

CANADIAN travel at the beginning of the last century was undertaken mainly by water, since streams and rivers were the only practicable routes. Highways on land led into unmapped swamps and wildernesses and often trailed off into mere forest paths. The traders and the missionaries, like the Indians, journeyed in canoes and other light craft. Long after this primitive method of travel had been superseded by coaches and sledges, there was still no sign of the railway in Canada. Travel by coach was a risky affair in several ways. Hotel keepers and drivers allied to cheat and rob their luckless guests and passengers. Their charges bordered on the fantastic, while freight rates both on land and water were exorbitant. A cannon weighing twenty pounds shipped from Montreal to Kingston cost a thousand dollars to transport, while the rate on a half-ton anchor came to something over eight thousand dollars. No nation with such obstacles could hope to expand. It was inevitable that a railway would have to come and solve the problem. In 1829, Peter McGill, of Montreal, and his associates formed the Company of the Champlain and St. Lawrence Railway. The line was to run from Laprairie on the St. Lawrence River to St. Johns on the Richelieu, and was to make connexions with New York boats plying on the Richelieu, Lake Champlain and the Hudson. Between Montreal and Laprairie the passengers were to be transported by steamboat. In 1836 Canada's first railway was opened to the public, but nobody dreamed that the tiny portage road of some fourteen miles would one day expand into a vast system of 24,000 miles, spreading across the entire continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific, extending away south and serving also the far cities of the north. The construction began in 1835, and a locomotive was ordered in September from the famous George Stephenson at Liverpool, and had to be ready for shipping in the following March. On Sunday, July 24, 1836, the first locomotive in Canada travelled from Laprairie to St. Johns—fourteen miles in forty-five minutes, hauling four passenger carriages and two loaded freight cars. The next day the regular timetable was inaugurated, the train making two journeys daily. For ten years or more this little railway played its part as the sole railway in Canada. There were difficulties attendant upon this pioneer line. The rails were of wood, to which iron strips were spiked, earning the nickname "snake rails," because the iron frequently broke loose and curled upwards, hitting the underneath part of the passing carriages. By 1852, however, the railway had thrust out its tentacles to the extent of forty-three miles and had joined the United States railways. Eventually it became the Montreal Champlain Railroad, and later was incorporated in the Grand Trunk system. The rapid expansion of Canadian Railways after their inception is one of the most remarkable occurrences in railway history. The Canadian Northern and the Grand Trunk Pacific railways opened up Western Canada for the settlers. The Grand Trunk Pacific trans-continental line was begun under government auspices, for the Government, on being approached for assistance, immediately seized the opportunity of taking a step towards the nationalization of railways.

The plan of construction was divided, the eastern section from Moncton to Winnipeg being built solely by the Government, while the western half from the coast was undertaken by the Grand Trunk Pacific, a new branch of the Grand Trunk Railway. Then the Government agreed that its nationally built system should afterwards be linked to the Grand Trunk, thus giving the private company direct communication across the continent. Until the Canadian Pacific Railway had begun, the Grand Trunk Railway enjoyed a monopoly, but the rival appeared and the original company decided that it, too, should have a trans-Canada route. After the surveys had been carried out, the constructors were faced, before a single rail could be laid, with building usable roads to carry materials. The rivers, flowing at right angles to the alignment, necessitated the construction of two hundred odd steel bridges in the course of a run of l,800 miles. The gradients were easy across the prairies. The low maximum gradient is still an outstanding feature of the Grand Trunk Pacific. One of the largest steel structures is the Battle River Viaduct ; and among the highest is the Pembina River Bridge, 213 ft. above the water. The railway entered the Rockies through a gap formed by the Athabasca River. It then followed the Fraser River, and met the Skeena River at Hazelton. The most impressive engineering feat was the conquest of the Cascade Mountains. Farther south these mountains presented the pioneers of the C.P.R. with tremendous problems which had to be solved by the introduction of steep gradients. But the Grand Trunk Pacific found a pass through which flows the Skeena River and negotiated the barrier on far flatter gradients than the rival route. The Pacific terminus chosen was Prince Rupert.

The second great Canadian railway, later amalgamated with the Grand Trunk, was the Canadian Northern. This railway, beginning with eighteen coaches, three engines and a hundred odd miles of rail, grew into a vast network of lines embracing 5,000 miles. The third great railway system forming to-day a part of the Canadian National Railways was the Intercolonial, opened in 1876, linking Montreal and Halifax in Nova Scotia. This was a Government-owned line built as a pledge on the Confederation of the Dominion of Canada. In the early part of the twentieth century the railway companies confidently expected that, in accordance with former experience, the influx of capital and the immigration of people from Europe would rapidly develop the lands in Central and Western Canada already opened up by the new lines, and result in an abundant and lucrative traffic. Immigration did increase, but the Great War came and the stream of immigrants stopped ; labour and materials became both scarce and expensive, and the cost of maintenance and operation of the trains steadily grew. The Canadian Government found itself obliged to make loans to the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway and to the Northern Railway. The Grand Trunk Railway was unable to continue the working of its new trans-continental line, and finally the Government was compelled to appoint the Minister of Railways as receiver. The stock of the Northern had been acquired two years earlier ; Steps were taken to consolidate the two railways, together with the Intercolonial Railway, under Government control, and the group to-day is known as the famous Canadian National system.

Since this amalgamation in 1922, the Canadian National Railway Company has made great progress. All-steel coaches have been standardized, and experiments have been made extensively with oil-electric locomotives. The company has also lent its support to a vigorous colonization policy. The C.N.R. now owns close on 24,000 miles of track. The railway operates a telegraph system of more than 160,000 miles of wire, and is responsible for a fleet of steamships linking Canada with Alaska, British West Indies, Australia and New Zealand.

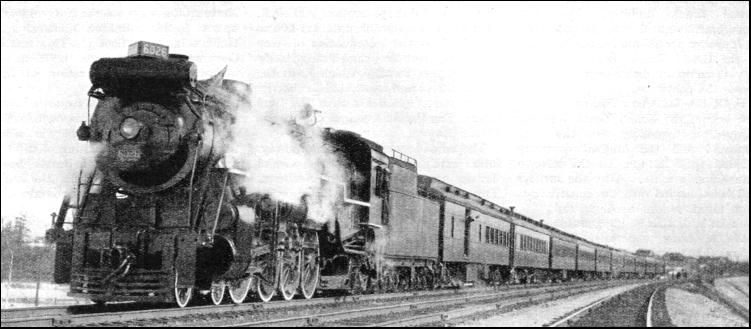

On a system of such a vast extent as this the express services naturally form one of the most important considerations. After the nationalization of the three groups the famous train, "The International Limited," continued to uphold its prestige under the new flag. The "International Limited," the king of the Canadian National's super-expresses, is one of the fastest services in North America. Including the many stops on its route, the express covers the journey from Montreal to Chicago via Toronto, a distance of 849 miles, in seventeen and a half hours, and the 334 miles between Montreal and Toronto take six and a half hours only. For a year or so the time was cut to six hours, bringing the average speed between these two cities up to 55.7 miles an hour, but owing to a pooling agreement between the C.N.R. and the C.P.R., the rival C.P.R. express ceased to run, and the increased weight of the "International Limited" necessitated an increase in journey time. This train has sped between the two great cities for over a third of a century. The "International Limited" leaves Montreal each day throughout the year on Canada's great double track route connecting Toronto, Hamilton, and Windsor with Chicago, where a connexion can be made with various United States services. At Toronto the traveller can change into the National express, which proceeds via Edmonton and Jasper to Vancouver on the Pacific coast. Comfort is the keynote of travel on these express trains. Among the varied types of sleeping accommodation is the modern luxury of the "chambrette," a small private bedroom. The dining cars are excellently served, and special menus are provided for children. In the colonist coaches, equivalent to third-class travel in Europe, the seats are convertible into sleeping accommodation, and passengers can prepare their own meals at a cooking range.

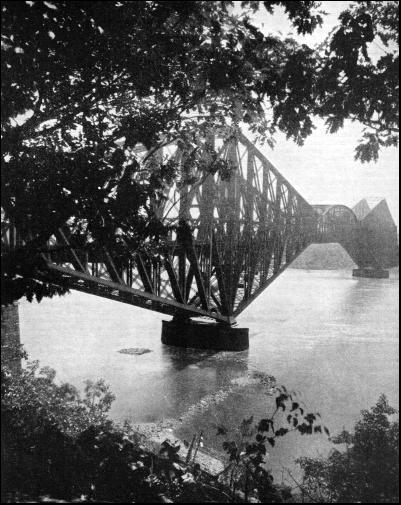

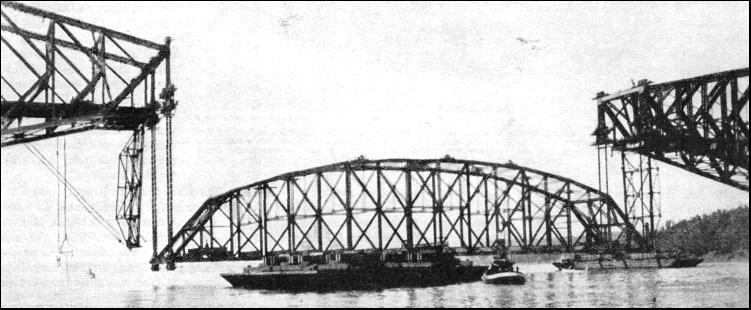

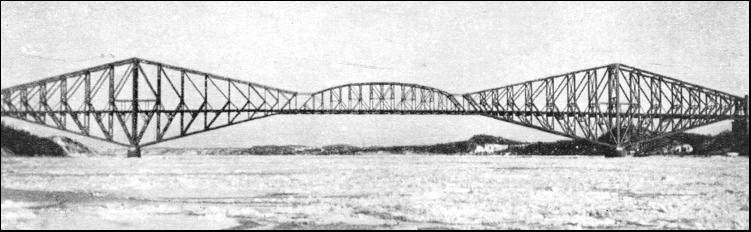

The crack trans-continental express of the line is the "Continental Limited," which operates daily between Montreal and the Pacific coast, doing the 2,929 mile journey to Vancouver in three days and seventeen hours, arriving there in the morning at 9.10 a.m., its route being via Ottawa, Winnipeg, Edmonton and Jasper. On the westward run the "Continental Limited" crosses a vast stretch of territory. From Ontario the expresses speed through the country north of the Great Lakes on to Winnipeg. In the Rocky Mountains, there is the world-famous Jasper National Park, close to Jasper Station. Jasper Park is the biggest game preserve in the world, having an area of 4,200 square miles. Many of the mountains in this vicinity top 7,000 ft., while Mount Edith Cavell, named in memory of the nurse who was one of the heroines of the Great War, soars up to 11,033 ft. above sea-level. When the express has left Jasper a marvellous panorama unfolds as the train thunders through the valleys of the Athabasca and Miette Rivers before approaching the Yellow Head Pass, at the summit of which is the Continental Divide. (Yellow Head Pass was the route originally proposed by Sandford Fleming for the Canadian Pacific Railway, but afterwards abandoned for the route via Kicking Horse Pass.) The third famous express of the Canadian National Railways is the "Maritime Express," which runs between Halifax in Nova Scotia and Montreal via Quebec, with a connecting line to Prince Edward Island, served by a train ferry across the Straits of Tormentina. The route follows, for part of the way, the southern bank of the St. Lawrence River. A few miles above the City of Quebec is the famous Quebec Bridge. This bridge is of the cantilever type and has a total length of 3,240 ft. The centre span, raised 150 ft. above the waters of the St. Lawrence, allows ample room for the passing of ocean steamers. It has a width of 1,800 ft., and is the longest cantilever bridge span in any part of the world ; the nearest rivals are the two 1,710-ft. spans of the Forth Bridge. Quebec is one of the most fascinating cities on the North American continent. In 1608 it became the capital of a country called New France, a position held, with one brief exception, until it was captured by Wolfe in 1759. For the fastest train services, such as the "International Limited" expresses between Montreal and Chicago, the Canadian National Railways use locomotives of the "Hudson," or 5700 type. With their six-coupled driving wheels and leading and trailing bogies, together making the "4-6-4" wheel arrangement, these engines are capable of maintaining eighty miles an hour, when necessary, with trains weighing 1,000 tons.

No. 5700 measures 92 ft. from the tip of the cowcatcher to the end of the tender. This tender can carry 20 tons of coal and 14,000 imperial gallons of water. The driving wheels are 6 ft. 8 in. diameter, developing a tractive effort of 43,300 lb. and an additional 10,000 lb. with a "booster." The "booster" is an auxiliary steam engine driving the trailing or rear bogie wheels under the locomotive cab, and is used principally to give the locomotive extra assistance when starting away. To attain the simplicity of line similar to that associated with British engines, practically all piping has been concealed and the sand dome, hitherto carried on top of the boiler, has been eliminated in favour of a sand chamber inside the smoke-box. This ensures perfect dryness of the sand, which is used on steep gradients or wet and greasy rails when the driving wheels develop a tendency to spin round without gripping. The sand effectively increases the necessary adhesion between the wheel tread and the metals. For the haulage of heavier loads a larger and still more powerful type, known as the 6100 class, is used, and provides a remarkable illustration of the progress in Canadian locomotive building during the last seventy years. If No. 6100 is compared with, say, a Grand Trunk locomotive built at Montreal in 1867, it would dwarf this veteran, for the boiler alone of the modern engine is practically equal in size to the complete engine of 1867, and its empty tender is also six times the weight of the old engine. The top of the smoke stack of the 1867 locomotive towered 14 ft. 10 in. above the track, flaring at the top like a blast furnace. This smoke-stack was half full of water, which served as a spark-arrester, a necessary precaution since wood was used as fuel. The sparks in shooting upwards hit a lid inside the chimney and dropped harmlessly into the water. On the modern locomotive, however, the size of the boiler leaves room for only a low squat chimney, in front of which, astride the smoke-box, is the cylinder of the feed-water heater, in the only position in which it could comfortably be stowed.

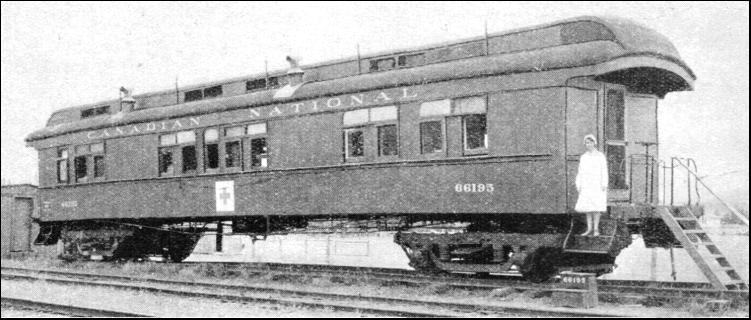

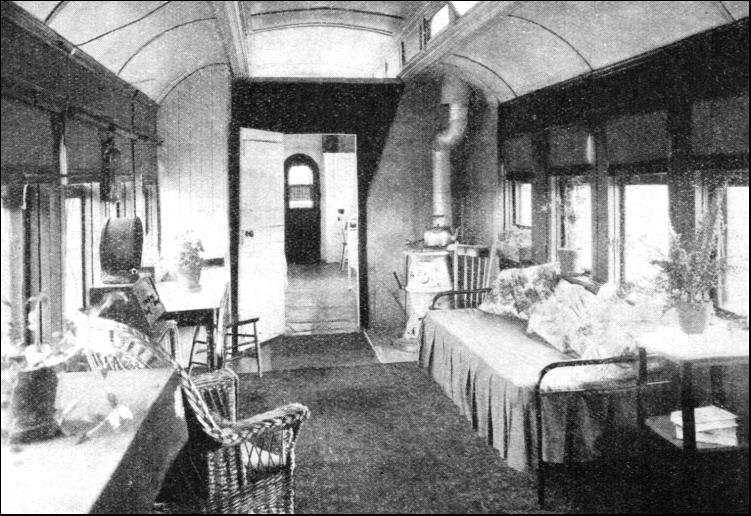

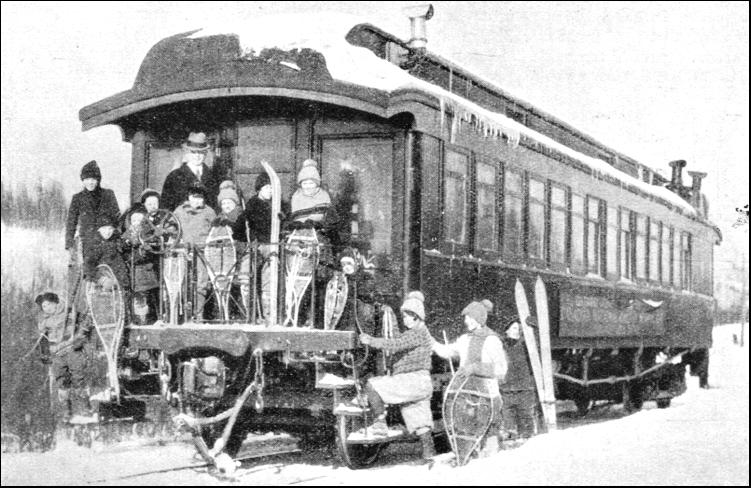

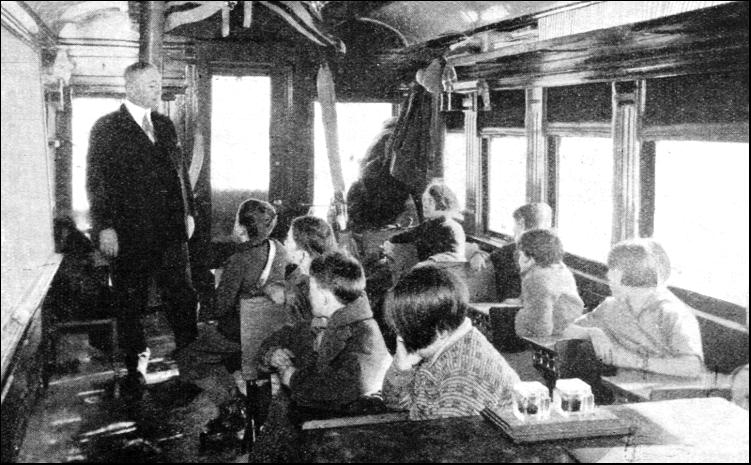

No. 6100, which has eight-coupled driving wheels 6 ft. 1 in. diameter, is of the 4-8-4 type, and weighs no less than 173 tons in running trim or, with her twelve-wheeled tender, 289 tons. The vast boiler has 5,246 sq. ft. of heating surface, and the firegrate, whose size, of course, demands mechanical firing, has an area of 84 sq. ft. ; the working pressure is 250 lb. per sq. in. The tractive effort of this monster is 56,785 lb., and by the use of the booster, similar to that of No. 5700, is increased to 67,700 lb., which is a pull of over 30 tons on the train. The Canadian National Railways also run Diesel oil-electric locomotives, and as far back as 1925 built an oil-electric car which made a record non-stop run of 2,937 miles between Montreal and Vancouver, completing the journey in sixty-seven hours and crossing the Rockies through the Yellow-head Pass at forty miles an hour. The cleaning of these giant modern locomotives is responsible for a considerable item in the overhead costs of any railway, but even if the advertising value of a smart appearance is disregarded, it is essential that the locomotives be kept clean, as an adequate inspection of the highly stressed working parts is quite impossible if they are smothered in dirt and dust. Quite recently the Canadian National Railways installed a locomotive washing plant at the Turcot engine house in Montreal, with the object of saving time and reducing cleaning expenses. The washing plant consists of an arrangement of pipes equipped with specially designed nozzles through which hot water at high pressure is sprayed on to the locomotive while it is slowly moving through the washing zone. The operation of the plant is purely automatic, and all that the driver has to do is to close the cab windows and ventilators and drive the engine forward very slowly. As the washing plant is approached, the front wheels close a low-voltage electrical circuit and the pipes swing into working position, an electrically operated valve opens and the water is automatically turned on. As the back of the tender leaves the spray-nozzles the electric circuit is broken, the valve closes, and the pipes swing back to their normal position. The area surrounding the plant is covered with a concrete floor with a low curbing, so that all waste water is drained off. The water used for washing is maintained at a pressure of 140 lb. per sq. in. by means of a motor-driven centrifugal pump which starts and stops automatically with the demand. The water is fed through a closed type heater in which the temperature is raised to about 150 degrees Fahrenheit. Before reaching the spray-nozzles, a small amount of cleaning compound is added, averaging about one gallon per engine. washed. This cleaning compound is made to a special formula, and serves a double purpose ; it assists in dissolving oil and grease on the surfaces to be cleaned, and leaves a light film of wax on the washed surface, which acts as a renovator on paintwork and as a rust preventive on bright steel. Another recent development on the Canadian National system is the introduction of school coaches. Owing to the continually shifting positions of the lumber encampments in Ontario, the education of the backwoodsman's children presented an extremely difficult problem until it was solved by the adoption of the school coach. Instead of the pupils going to school the school comes to them. The school coaches are run into convenient sidings near the biggest lumber camps. They contain everything appertaining to classrooms : desks, blackboards, maps and bookshelves. Owing to the extremely low temperatures of the northerly regions into which these movable schools penetrate, great attention is paid to the problem of supplying adequate warmth, and the provision of large stoves is imperative. In these snow-clad regions it is no uncommon thing to see the children going to school on skis, sleighs or snowshoes. The part played by the railway in bringing the benefits of modern civilization to these desolate parts is also illustrated by the Red Cross coaches. These vehicles are fitted up as travelling hospitals and convey doctors and medical assistance to outlying districts. If the patients are too seriously ill to be treated on the spot they can be smoothly and swiftly transported to the nearest hospital. Another interesting and unusual sidelight on the Canadian National system is the fire-fighting appliance fixed to locomotives. This can be utilized to quell fires on the train itself, on other trains in goods yards, or on the track side. The water in the tender is directed on to the fire by means of a pump on the engine. Specially equipped fire-fighting trains are also in extensive use to combat the menace of forest fires along the sections of the route which run through heavily-wooded regions. In yet another way the Canadian National Railways' administration is unique, in that it owns its own chain of broadcasting stations, from Moncton in the east, right across Canada. These are used for the entertainment of passengers in the trains, the principal of which are all radio-equipped, and also for the instruction and amusement of Canada generally.

Many thanks for your help

|

Share this page on Facebook - Share  [email protected] |