|

|

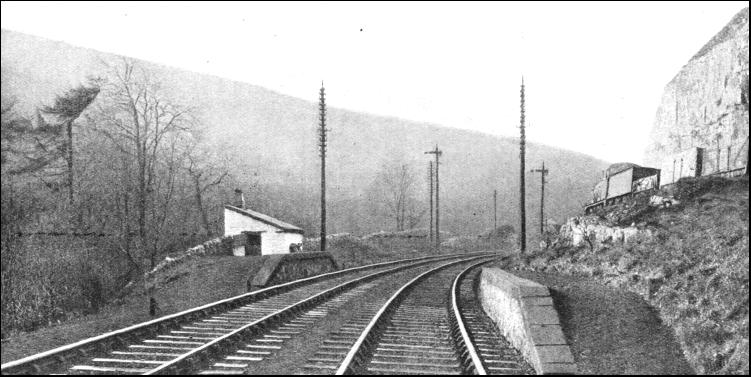

BECAUSE it sees so much of the drama, the comedy, the tragedy and happiness of life, a station—whether it is a mighty terminus, or a tiny country station—presents one of the most romantic aspects of railway working. There is romance in the sight of the train waiting at a platform, herald of a challenge to time and distance. There is romance behind the comings and goings of its passengers. And there is romance in the spectacle of the mail-bags as they are thrown into the vans to be sorted, while the night mail thunders through the darkness at sixty miles an hour. The railway station is the pivot of it all. But behind that is a smooth-working organization, the efficiency and ability of which to meet successfully all sorts of emergencies are based on long experience, personal supervision and faultless staff-work. There are in Great Britain something like 6,700 passenger stations of every conceivable type, size and importance. The smallest of them all is Blackwell Mill in Derbyshire, where the tiny platforms can accommodate only one coach apiece, and the service consists of two trains—one in either direction—on one day of the week only. The largest is Waterloo, the principal London terminus of the Southern Railway, which has 21 platforms, deals with 1,550 trains and 120,000 passengers each week-day, and covers 24-1/2 acres of ground. Through London's great termini there flow daily some 1,130,000 people. The provinces, too, have their great terminal stations—Glasgow (Central, St. Enoch and Queen Street), Liverpool (Lime Street, Central and Exchange) and many others. Yet it is probably at the great junction stations of the provinces—York, Crewe, Bristol and Carlisle—that the interest and problems of station operation are revealed to the maximum extent. For through these great clearinghouses trains pass to and from almost every part of the country. Stand for an hour or so on Crewe Station in the middle of the day and you will see something of the real wonders of railway working at close hand—see, too, something of this intricate organization and machinery that make possible the smooth, seemingly effortless interweaving of the close-laced pattern that is our railway system.

Crewe—the "Clapham Junction of the North"—is perhaps the most famous railway junction in the world. Situated 158 miles from London on the historic West Coast main line to the North, it is the natural radiating-point at which the north line is intersected by others connecting Liverpool, Manchester, Chester and North Wales (the route of the Irish Mail), Stoke-on-Trent and the Potteries, Shrewsbury, Hereford, South and Central Wales, and even Bristol and the West of England via the Severn Tunnel. A century ago Crewe consisted of a farmhouse standing in lush fields—for this is a famous "dairy" country. Then came the pioneer Grand Junction Railway that passed through Crewe on its route from Birmingham to Liverpool, forming ultimate connexion with Manchester, Chester, and so on—and the metamorphosis of Crewe had begun. Here, 95 years ago, was established a building for "the clerk of the station," as the station-master was called by a contemporary writer of the period. Here, too, was an engine-house with one spare engine. Evidently Crewe did not suggest itself to the writer of those early days as the potentially enormous railway nerve-centre which it has since become, with a station covering twenty-three acres. Where once stood the farmhouse now spreads a busy industrial town. It has a population of 46,000 people, 5,600 of whom are employed at the London Midland and Scottish Railway's great locomotive works. These works cover no less than 160 acres, but they and their wonders are a story in themselves. We are concerned now with the traffic that filters through this immensely important strategic centre. Assuming that we are travelling down to Crewe from London in winter, when the "Royal Scot" stops at Crewe, the first indication that we are approaching this great centre is a slackening of the train's speed as it descends the Whitmore "bank," and the appearance on the "down" or left-hand side of the train of an enormous expanse of goods sidings, known as the Basford Hall Yard. Here the various freight trains are broken up, sorted and re-assembled for dispatch to all parts of the system. Here also there is a big Tranship Depot, for transferring individual consignments, not sufficiently numerous to make up complete wagon-loads, from one wagon to another that is bound for the same ultimate destination. Running slowly past the Crewe South Junction signal box, where a gleaming array of electric levers controls all movements at the south end of the station, we notice lines coming in on the left and right from the Shrewsbury and Potteries lines respectively. Our train passes under the great Crewe south gantry with its forest of semaphores, and draws up in the station. If it were summer time, when the "Royal Scot" does not call at Crewe Station, we should run through on one of the middle tracks, independent of platform ; as it is, we use one of the six platforms that give through access from north to south, or vice versa. Four of these six platforms are arranged with a cross-over track about half-way down their great length, so that if necessary two trains can use one platform at the same time. The longest platform is over 1,500 ft. in length. In addition, there are ten "bays," or short terminal platforms ; these are used by trains of a more or less local character, which start or finish their journeys at Crewe. The aggregate length of Crewe's sixteen platforms is 11,394 ft. For the moment we shall not concern ourselves with the operations within the station itself ; let us walk to the north end of the platform, where, from the vantage-point of the great over-bridge that leads to the locomotive works (the longest overland suspension bridge in the country), we see that the main line forks three ways immediately beyond the station. The left-hand line goes to Chester and North Wales ; that immediately in front to Preston and Scotland (the Liverpool line leaving it at Weaver Junction, 16 miles or so to the North) ; while the right-hand line leads to Manchester.

To the left are the locomotive running sheds, where something like 150 engines arc housed. This is the north shed ; we should have noticed, as we ran into the station from the south, another huge depot where there are about 100 engines stationed. The north shed houses principally passenger engines, and the south shed those for freight traffic ; 250 engine in all—a striking contrast with the solitary "spare engine" commented upon by our historian of 1840. While we have been waiting at Crewe strange things have been happening to the "Royal Scot" in which we arrived from Euston. While the driver has been "going round" his engine, to make sure that all is well for the non-stop run of 150 miles or so to the Border, a busy little shunting engine—or "station pilot "—has unobtrusively backed on to the three rear coaches and shunted them away to another platform, where they have been added to an express for Perth, Aberdeen, and Dundee, which is to follow the "Royal Scot" after a few minutes' interval. When we consider that this train in turn will have to be broken up again at Perth, and formed into a series of new trains, we get some idea of the complexity of station working. Meanwhile, on another platform, two south-bound trains have run in from Liverpool and Manchester respectively, and have been marshalled together to form a complete train, which, in a few minutes, will leave for Shrewsbury and Hereford—eventually to be re-formed into still more trains for South Wales, Bristol, and so on. If we want to find a really striking instance of many trains in one, let us consider the 7.30 p.m. sleeping-car express from Euston to Scotland—the "Royal Highlander"—which sets out from London pulling through-carriages for such diverse destinations as Oban, Turnberry, Dundee, Aberdeen and Inverness ; or the 5.20 p.m. from Euston, which conveys through portions for Holyhead, Birkenhead, Blackpool and Barrow-in-Furness, all of which are sorted out at Crewe, Chester and Preston. "Composite" trains frequently include not only through coaches for different destinations, but also through portions of from five to six coaches, with two or more self-contained catering units. These are the passenger-carrying aristocrats of the railway. With the less conspicuous but none the less important "night flying squad"—the mail and parcel trains—the work of re-marshalling at such important centres as Crewe, Bristol, Carlisle and York is even more intricate and intensive. Passengers are animate, and if there is no through coach and they do have to change trains, they can walk across a platform. But mails and parcels are inanimate, and have to be carried or trolleyed from one train to another. That is why these big junction stations are such hives of humming industry when the average person is asleep.

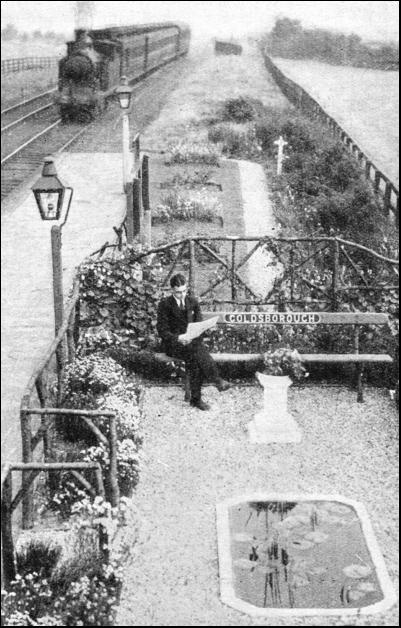

Armies of railway and postal workers are busy transferring mails and parcels—the latter term embracing everything from boxes of butter to crates of poultry—while the little "station pilot" engines descend on a train as soon as it arrives, split it up into an assortment of individual vehicles, and bustle these off to attach them to other trains ; meanwhile other pilot engines arrive and attach to the skeleton trains other vehicles which have, in turn, been taken from other trains. The controlling organization behind this system at Crewe is in the divisional control office for the Western Division of the L.M.S. Railway. This department controls, surveys and adjusts the whole of the passenger and freight operations between Euston in the South, Carlisle in the North, Holyhead and Liverpool in the West, and Swansea and Abergavenny in South Whales. Some 40,000 miles of telephone wires connect it with every station, every engine shed, and the score or so local district control offices throughout the division. No train can move anywhere in this vast area without "Control" knowing of the movements within a few seconds, and the information which the department collects and dispenses is of inestimable assistance to station-masters and other local officials in the solution of their own immediate problems. This, then, is the unseen but all-seeing brain. What of the man on the spot, who is responsible for his own station ? His duties vary widely according to the size of the station of which he is in charge. The country station-master often has the care of two or even three small stations. He is responsible for the staff of the booking-office, platform and signal-box, and has to pass a strict examination in the intricacies of the block signalling system. Not only is he responsible for the actual working of both passenger and freight trains while at his station, but he must also sec that the signalmen are at their posts and carrying out their duties efficiently, scrutinize the booking-office accounts (and sometimes issue the tickets himself) ; he must see that goods wagons in his station yard are properly in position and that no wagon-sheets are insecurely fastened, and must fulfil many other duties of an operating nature. The station-master must be something of a salesman ; he must keep a watchful eye on the development of traffic in his small district, must visit factories and farms, organizers of outings and school-treats for canvassing purposes—must, in fact, be a jack-of-all-trades and master of them all ! The responsibilities of a station-master at a larger station, such as Birmingham or Sheffield, are less diffuse but more onerous. He is concerned almost solely with the working and management of the station itself. The canvassing and development of traffic is the responsibility of separate officials known as passenger agent and goods agent respectively. The staff of a station-master at one of the main-line termini may be so large that a separate section of his establishment, termed the Station Staff Office, will be required to supervise staff matters alone. Men as well as machines must be organized, and arrangements have to be made for adequate staffing of all platforms, exits, ticket-barriers, concourses and cab-entrances, at which the requirements will vary considerably from one period of the day or night to another.

The station-master must be fully acquainted with his trains and his timetables. This means more than a mere knowledge of the arrival and departure times and appropriate platforms of, perhaps, two hundred trains a day. He must know which train detaches some of its vehicles, which train changes engines, and which train must draw down to the end of its platform so that the engine may take water from the water-crane. Some trains either give or receive a heavy parcels transfer traffic, and men must be ready with their platform barrows when these trains come in—not only on the platform, but also with each barrow, loaded with traffic for separate destinations, positioned at the exact spot at which the parcels van conveying traffic for that destination will stop. Individual trains have their own peculiarities. Some trains, for instance, can attach extra passenger coaches only at the rear, as there are four through fish vans from elsewhere marshalled next to (or "inside") the engine ; the 11.55 p.m. to London must load passengers for the metropolis only in the first eight coaches, since the last four go only to a certain destination—except on Saturdays, when the portion for that destination does not run. All this is day-to-day routine work. But the station-master must always have his mind fixed on the possibility of exceptional circumstances arising. The busy Saturdays in the summer, for instance, when many extra and relief trains will be running. Platforms must be found for these trains, not haphazardly but on a previously determined plan. Such and such a train will change engines (that means that the siding at which the station-master used to hold empty milk vans for a night train will be required by the waiting engine, and that the milk vans will have to go elsewhere) ; such and such a train must be worked for ticket examination while it is at the platform, and inspectors must be provided for this purpose. Coaches have to be found for all extra trains run during the summer and on special occasions—when, for example, there is a big football match at a nearby town. These coaches cannot be taken haphazard from sidings. The working of every coach on the system is governed by daily diagrams ; these must be consulted, and definite arrangements made as to which spare coaches will be utilized for which trains; where they will be serviced, and by which service they will return. All this has to be arranged in consultation with the responsible officials, and everything connected with the train, from the engine-crew down to the tail-lamp, fixed to the last detail. Nor can the extra train be released on the line when a suitable interval occurs ; a proper "path" must be found in which it will run, with the principal passing times shown. Printed lists giving these details are circulated to the staff concerned. Not all these problems are the immediate responsibility of the station-master, but he is concerned with their ultimate success. At all large stations printed pamphlets are circulated to the staff giving particulars of all the passenger trains that run regularly (including standard and conditional relief trains in tlie summer) ; the times at which they will stop at the station ; the platforms they will use ; and any work that requires to be done with them in the way of attaching or detaching through vehicles. A similar pamphlet is used for the locomotives, showing which trains change engines, and what happens to the engines after they have been detached—whether they go to the engine-sheds or whether they take up another train-working almost immediately. Over and above all this, the station-master has to legislate for arrangements that are made almost at the last minute in respect of special vehicles conveying racehorses, private motor-cars, and other traffic. Finally, the station-master has also to spend part of his time attending meetings in connexion with impending events, or discussing alterations and other matters with the company's officials either at headquarters or on the spot.

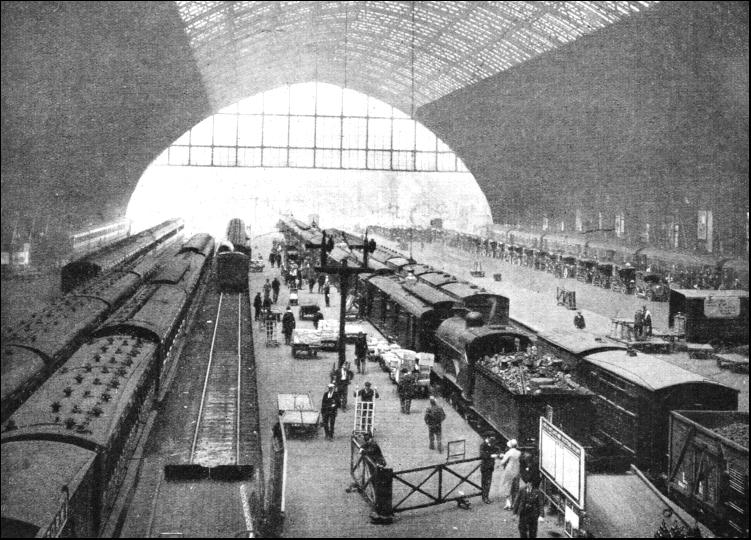

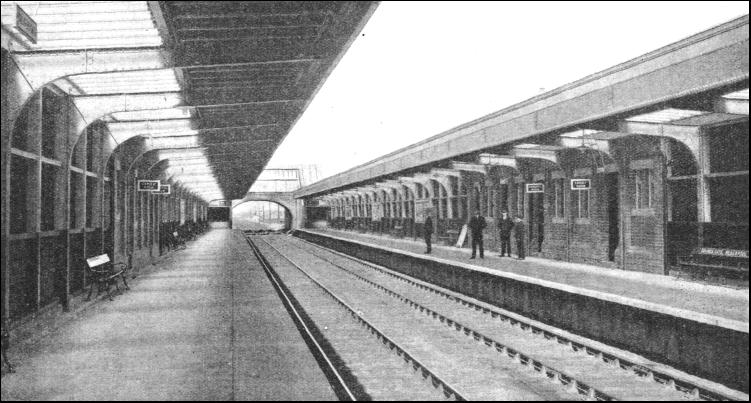

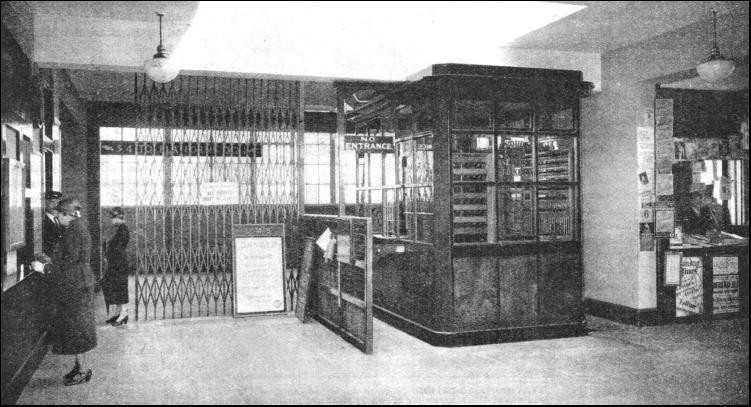

The working of a large terminal station is less varied than that of an important junction, but none the less interesting. Here the objective is not so much the maintenance of scheduled connexions, transference of through vehicles, and fulfilment of the functions of an efficient traffic "filter" ; but rather that of dealing with the maximum amount of traffic with the minimum amount of unprofitable platform occupation. Every movement, whether of a 15-coach train or of a light engine, costs time (and time is money to the railway), and the more efficient the movements are at a terminus, the less is the risk of delay on the line itself. An empty train backing out of a platform later than scheduled may, for instance, cause an incoming train to be stopped by signals outside the station while the tardy movement takes place, and this delay may have a repercussive effect on following trains. A train leaving a terminus five minutes late may miss its "path" at an important junction outside, and cause other trains to be delayed. Here are just a few examples of how movements are saved in terminal working. The engine that brings the empty train from the sidings into the platform to load would, in the ordinary way, wait for its train to leave and then follow it out. That means two signalling movements through the platform instead of one, so the engine pushes the train out to the platform end, thus giving the departing train a "leg-up" at the start as well as saving a movement. At some big stations, such as Euston, separate lines exist which not only enable empty trains to be brought into the station without interference with the main running lines, but also enable the empty coaches of arriving trains to be withdrawn in a similar manner. Innumerable other instances could be given of the way in which our great railways save time and money by the intensively efficient management of their stations. Everywhere stations are becoming more scientifically equipped and more decoratively attractive ; illuminated train indicators, mechanical conveyers for parcels, brighter waiting-rooms, and cosy cafeterias, electric devices for giving the right-away signal at long platforms, loud-speaker telephones for communication between the staff—these are signs of station progress. It is difficult now to realize what apparently insuperable obstacles confronted the railway companies when they sought to establish stations at the big cities. The building of the London & North Eastern's terminus at King's Cross, for example, presented many disturbing problems. Of necessity it had to be east of Euston, and the most favourable situation was found to be at King's Cross ; but as it was not immediately available, a provisional depot had to be established three-quarters of a mile distant at York Road. What is now the metropolitan terminal of the London & North Eastern was originally a smallpox and fever hospital. the removal of which cost £60,000. Upon the space thus cleared rose an unpretentious structure with two platforms—that on the west side for the outgoing and that on the east side for the incoming trains. The original station was opened in 1852, two years after the railway was completed, and at that time it was one of the largest terminals in existence. Externally it has few attractions, but its arched roof is considered a fine example of engineering. The present building is 800 ft. in length, and the roof span is 105 ft., with the centre 71 ft. above rail level. In the first instance the ribs of the roof were of laminated timber planks, overlapping one another lengthways, but in the course of a few years the wood was found to be ravaged by decay. Accordingly reconstruction was taken in hand ; the eastern half was replaced by wrought iron in 1869-70 ; while the western half was rebuilt in 1887-8. Growth of traffic soon demanded the provision of additional platform accommodation, and this was supplied by turning the space in the centre of the station to this account. Subsequently the suburban business necessitated still further terminal facilities, and this requirement was satisfied by a local station. King's Cross terminus to-day covers 15-3/4 acres, and has sixteen platforms, in and out of which more than 500 trains move every day. Modern development and improvement in railway work have assisted the station-master and his staff in the performance of their duties. But, on the other hand, progress has added considerably to the work of the railwaymen. An example readily called to mind is the electrification of suburban lines round London which have resulted in enormous increases in passenger traffic. The number of trains in and out of such great London stations as London Bridge, Cannon Street, Waterloo and Victoria has multiplied again and again since the early days when trains were hauled by steam locomotives. The London termini have, however, overcome difficulties as they have arisen. Increases of area have in most instances been impossible, but the measures taken by officials to deal with the ceaseless flow of passengers have greatly eased the situation. Platforms have been lengthened, additional bridges built, and subways have been constructed. Colour-light signalling and power operation of points have also contributed to the rapid handling of the trains. So the railway station changes with the times. Yet it will always preserve its spirit of romance, inseparable from the trysting-places of those who travel. But to some people the greatest romance of all lies in the organization behind the working of a great station.

Many thanks for your help

|

Share this page on Facebook - Share  [email protected] |