|

|

THE chief advantage of a train ferry lies in the fact that it saves any transference of goods. Wagons can be run on to it at one port and off it at the other, so working through from start to finish. Where fragile goods are concerned all risks of breakage by handling at the ports are avoided. Perishable goods also derive considerable benefit from a train ferry. Greater speed in transit has enabled more business to be done between Continental countries. Although it is becoming an increasingly vital factor in modern commerce, the train ferry is not a new idea. Long before the Forth Bridge had been built railway wagons were carried across the Firth of Forth from Granton pier at Leith to Burntisland, on the Fife coast, to avoid transhipment of their loads. The same thing happened south of Dundee, where the Firth of Tay was spanned by a ferry from Tayport to Broughty, until the Tay Bridge came into being. The train ferry system is seen at its best in the Baltic. Denmark consists, in the main, of Jutland, a peninsula physically joined by Schleswig-Holstein to the mainland of Europe ; the large island of Zealand on which the capital, Copenhagen, is situated ; and, between the two, the island of Funen. Between Jutland and Funen there lies the Little Belt, and between Funen and Zealand the Great Belt. But the railways in Zealand are linked with those in Jutland by two train ferries, which make through rail communication possible between the port of Esbjerg and other Jutland towns and Copenhagen. A journey from England to Copenhagen by the mail route across the North Sea from Harwich to Esbjerg necessitates a trip on a train ferry. At Esbjerg the traveller enters a through sleeping-car train for Copenhagen, and after a run of fifty-five miles across Jutland, Fredericia is reached. From here the two-miles crossing of the Little Belt is made. By smart working the train is run on to the ferry steamer in fifteen or twenty minutes ; the crossing itself takes fifteen to twenty minutes, and another fifteen minutes is needed at Strib to run the trains off on to land again and re-marshal. Next comes a run of fifty-two miles across Funen, which brings the train to Nyborg, at the west side of the Great Belt, where the same procedure must be repeated. But the Great Belt is sixteen miles wide, so that the train-ferry requires from seventy-five to eighty minutes for the crossing; and with the same time as before for the transfer from rail to ship and from ship to rail at the ports ; the total working out at not less than an hour and three-quarters. The two water crossings between them, therefore, consume about two and a half hours of the journey, though their combined length is only eighteen miles. Finally, a run of sixty-eight and a half miles takes the train from Korsoer, on the east side of the Great Belt, into Copenhagen. So efficiently are the trains run on and off the ferries that many travellers are unaware that they have made anything other than an ordinary railway journey.

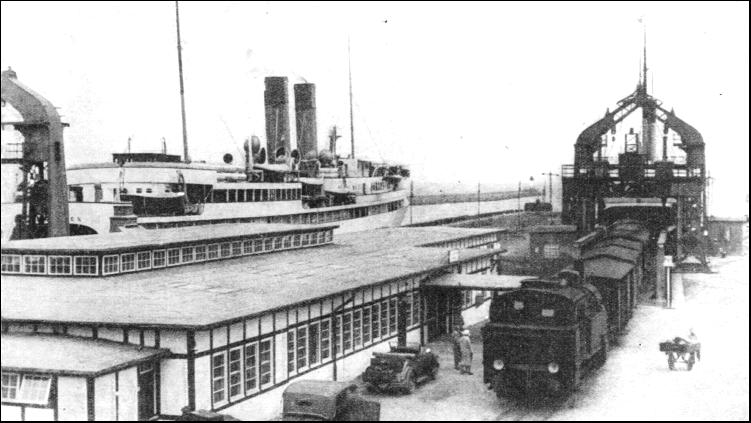

Similar conditions prevail in approaching Copenhagen from the south. Through sleeping cars are run daily between Berlin, Hamburg and Copenhagen, but there is a wider crossing over the Baltic. The German train brings the passenger as far as Warnemünde, 145 miles north of Berlin on the Baltic coast. From here a large and powerful ferry-steamer takes the coaches twenty-five miles across the water to Gjedser, where the train is transferred to Danish metals. But not for a lengthy railway journey, for twenty-eight miles of railway suffice to cross this small island, after which another three miles of water, from Orehoved to Masnedo, intervene before the train is on the main island of Zealand. Two hours are needed for the main train ferry crossing, from Warnemünde to Gjedser. Twenty minutes or so can be added for the short crossing and more than an hour for the four movements of the vehicles on and off the ships, so that from reaching Warnemünde to leaving Masnedo, only fifty-eight miles away, from four to four and a half hours must be spent. Finally, there comes a seventy-six miles run by rail from Masnedo across Zealand to Copenhagen.

In order to curtail these journeys and speed up these through services, the Danish Government decided to embark on two ambitious projects, the first of which has already materialised. An immense steel bridge has been thrown across the Little Belt, and the trains will be able to run through from Esbjerg, Aarhus and other Jutland towns to Nyborg, so that only the Great Belt crossing by water will remain. By this means it will be possible to accelerate the service by forty minutes. The famous British firm, Dorman Long, which built the Sydney Harbour Bridge, undertook the bridging of the strait between Orehoved and Masnedo, by an enormous cantilever structure ; a splendid work to vie with the biggest bridges in the world. It is a matter of no small pride that this contract was secured in the teeth of strenuous competition from bridge-builders abroad. The object is to enable fast through running by rail from Gjedser to Copenhagen, and an acceleration by fully an hour of the journey from Hamburg or Berlin to Copenhagen may be confidently expected. But the longest of all the Baltic train ferry crossings is the direct service between Germany and Sweden, which crosses from Sassnitz, on the German island of Rügen, direct to Trelleborg, near Malmö in Sweden, a distance of fifty-eight miles. This service, operating at night, was brought into operation jointly by the German and Swedish Governments, each contributing two vessels to the fleet ; the total outlay on the scheme was approximately £1,000,000. The Germans built their own two vessels ; of the two Swedish ships, one was built in Sweden and the other in Great Britain.

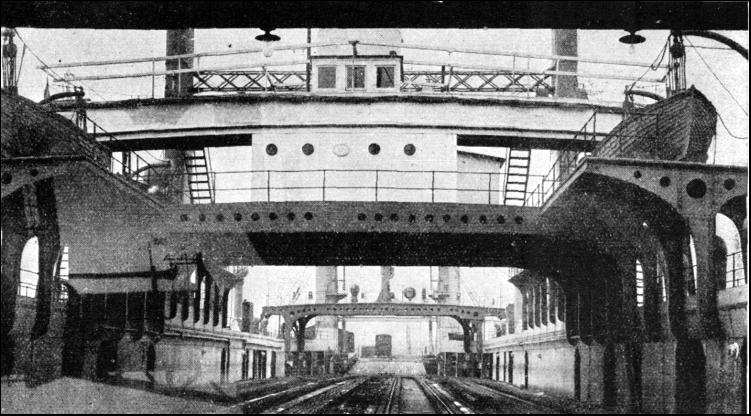

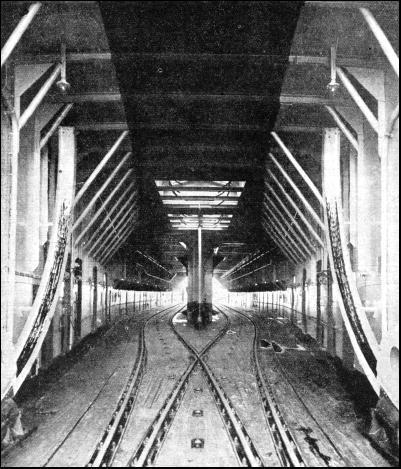

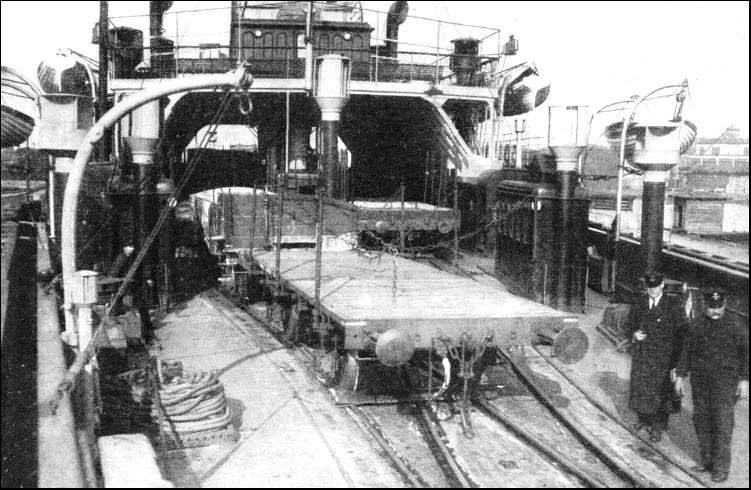

The Swedish train-ferry "Drottning Victoria" may be taken as typical of the four, all of which have similar dimensions. She is 370 ft. in length and 54 ft. in the beam ; her draught when loaded is 16-1/2 ft., and her displacement 4,270 tons. To complete the sea journey of fifty-eight miles across the Baltic in four hours, a maximum, service speed of 16-1/2 knots is needed. The main deck, entered from the stern, carries two tracks, each 295 ft. in length, and is capable of accommodating eight passenger coaches, in two rows of four each. The size of coach permissible may reach a total height of 15-1/4 ft., with a width of just over 11 ft., which are the maximum dimensions allowed on the railways of Germany and Sweden. A system of trimming tanks on the vessel enables her to accommodate herself to the level of the rails at the terminals, according to the state of the tide. To secure the coaches during their sea journey, heavy shackles are fitted, both inside and outside the track, the former 4 ft. 4 in. and the latter 8 ft. 8 in. apart. Corresponding shackles are provided on the coach-frames, and by means of specially-designed screws the shackles on the ship and those on the cars are secured tightly together. To prevent the coaches from swaying in heavy weather, similar screws are used to connect the roofs of the cars with the deck girders on both sides. In addition to these precautions, jacks are placed beneath the coaches, and are extended to take the compression off the coach springs.

Some passengers, especially those travelling in the sleeping-cars, prefer to remain in their coaches, and for their benefit the steam-heating connexions on the train are coupled with the heating system of the ship during the voyage ; electric bell communication between the cars and the ship's stewards is similarly established. But excellent accommodation is provided on board, including dining-saloons, lounge, and smoking-rooms on the promenade deck, as well as cabin accommodation below the car deck for 140 passengers. Two large searchlights are fitted, one forward and one aft, to assist in berthing the vessel. To facilitate entry into the ferry terminals, there is a bow rudder, in addition to the usual stern rudder ; the former is locked by a bolt in the neutral position during the voyage. Accommodation is provided on board for a postal staff, who sort the mails on the steamer, as well as for the customs officials, who also do their work on the trip. Through sleeping-cars are run by the Sassnitz-Trelleborg route between Berlin and Stockholm, twice daily in each direction, the through journey taking from nineteen and a quarter to twenty-one hours, and also between Berlin and Oslo, Swedish coaches being used in both directions. Through coaches and sleepers are also run between Hamburg, Stockholm, and Oslo. Another way in which through coaches cross from the German mainland to Sweden is by the Warnemünde-Gjedser ferry already described, then across from Orehoved to Masnedo, and last of all from Copenhagen to Malmö in Sweden—three ferry crossings in all. The total number of train-ferries in and around the Baltic, therefore, in which passenger trains are carried, is six ; three of these, which ultimately will be reduced to one (across the Great Belt), are exclusively Danish ; one joins Denmark with Germany, one joins Germany with Sweden, and the remaining one joins Sweden with Denmark.

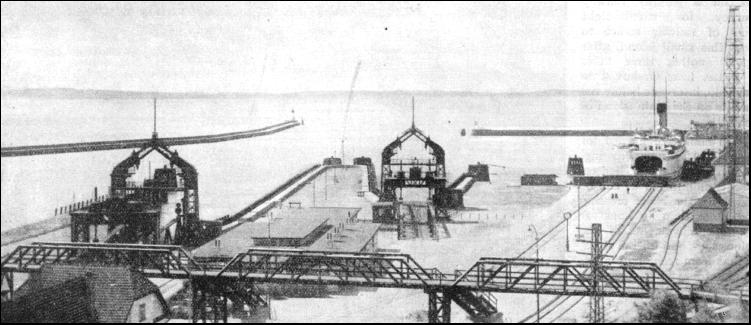

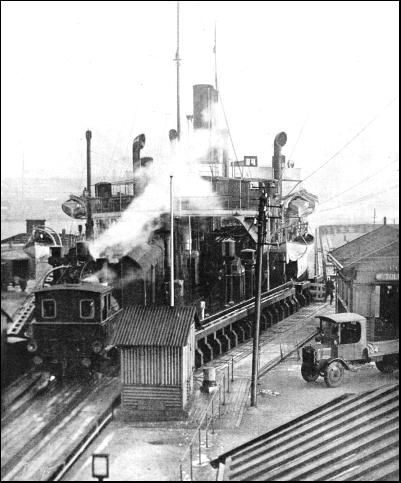

During the war it became evident that, if some method could be devised of running munitions and guns across the English Channel without having to load them on and off ships at the Channel ports, a great deal of time and labour would be saved. The simplest solution was a train ferry ; and this led to the establishment of an entirely new port, on an inlet of the Kent coast between Ramsgate and Sandwich, called Richborough. Here a train-ferry terminal was constructed, with a corresponding terminal on the French side at Dunkirk, and through all the later stages of the war both ports were kept busy. Another similar train-ferry service was run between Southampton and Havre. After the war these services, having fulfilled their valuable function, ceased to operate. But it was felt that the principle thus established ought to be perpetuated, and so a company was formed to take over the ferry-steamers which had operated during the war between England and France. After a good deal of thought and planning, Harwich was decided on as the terminal on this side of the water, and Zeebrugge, in Belgium, as the Continental port. The company began its services in 1924, and took the name of "Great Eastern Train Ferries, Ltd.," owing to the lengthy association of the late Great Eastern Railway and its Continental steamer services with Harwich and the adjacent port at Parkeston Quay. The train ferry service is now worked by the London and North Eastern Railway. Special wagons have been built for the ferry service. They are easily recognizable, when running on this side of the water, by their inscriptions, in various Continental languages. Rather longer than the average covered wagon in this country, and painted white, they form a prominent object in any freight train in which they may be marshalled. Each of the ferry-steamers on the service is provided with four tracks, and can accommodate a total of fifty-four of these wagons. Notwithstanding the North Sea gales, not a single one of the nightly trips of the Harwich-Zeebrugge service has been missed, nor has any casualty occurred to a wagon during the crossing.

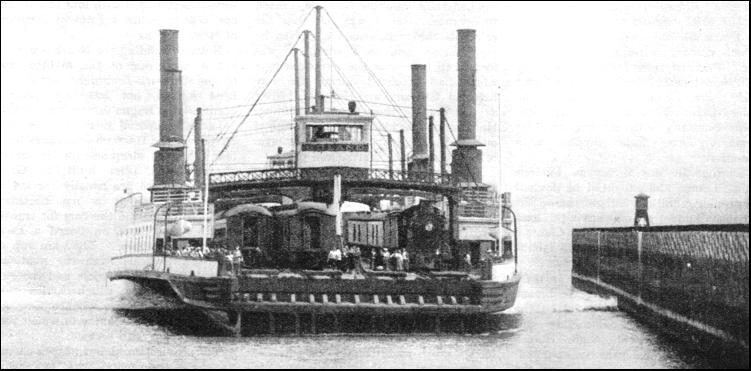

Loads of special interest have often crossed by the Harwich-Zeebrugge ferry. Many of the sleeping-cars in service abroad have been built in Great Britain. These are usually carried on train ferries, as it is not necessary either to dismantle the cars for transit, or to swing them on board a cargo ship and off again. They are run on their own wheels from the manufacturers' works to Harwich, and there on to the train-ferry, which carries them across to Zeebrugge, whence they are run direct to the country in which they are to be put into service. The heaviest consignment ever carried by this train-ferry was the giant London and North Eastern express locomotive "Cock o' the North," 165 tons in weight complete with tender, which travelled this way from England to Paris, when being taken to the research station of the French railways at Vitry for exhaustive testing. The engine returned by the same route. Communication between the ship and the shore, at the terminals, is made in the customary manner by means of a lifting bridge, which is hinged at the shore end, and coupled at the outward end to the vessel. In this way wagons can be run on and off the ship at all states of the tide. At high tide the vehicles run on an up-grade on to the rail deck, and at low tide they run downhill. Recent developments enable passenger services across the English Channel by train ferry to be considered. Many years ago there was a strong agitation for a tunnel to be bored under the English Channel, and work was begun on this vast project. The total length of such a tunnel would have been fully twenty-five miles, and the cost considerable ; it was doubtless the latter factor, rather than engineering difficulties—which were not expected to be serious—that brought the work to a standstill. Various other projects have been devised for bridging the Channel, but the simplest substitute—that of a ferry—has many advantages. It does not abolish the water-crossing, of course, but it does make possible the through transit of passengers, in comfortable sleeping-cars, from London to Paris. This is probably, only a beginning, and later we may expect to have through transit provided from London to places much farther afield in the heart of Europe. Three ferry-steamers have been built to ply between Dover and Dunkirk. The terminal on the French side is, of course, already in existence ; it is the one which was used throughout the war. But the terminal on the English side at Dover had to be specially constructed for the new service. One of the most remarkable train-ferry steamers in the world has, in the winter-time, to add the business of ice-breaking to that of transporting the trains. In the Gulf of St. Lawrence, at the mouth of the St. Lawrence River in Canada, there lies Prince Edward Island, on which some 261 miles of railway have been laid. This large island is separated from the mainland by Northumberland Strait, of which the narrowest portion, nine miles in width, lies between Cape Tormentin, at the extreme south-east corner of New Brunswick, and the port of Burden, in Prince Edward Island. Approximately an hour is needed for the steamer crossing when water conditions are normal. But during the winter months the crossing is reminiscent of a trip to the Arctic. The strait has become a mass of ice from one side to the other. It is, furthermore, a broken and irregular barrier, in confused masses, for pack ice comes drifting in from the Gull of St. Lawrence, in which there are present huge rugged hummocks of ice, intersected by stretches of open water, and areas of broken ice and water, known as "lolly," in which navigation requires a good deal of expert knowledge. For many years communication was maintained by the Government steamers "Stanley" and "Minto," specially designed for icebreaking. Now their place has been taken by the powerful icebreaking train ferry steamer Prince Edward Island, which makes the connexion, twice daily in each direction, between the main system of the Canadian National Railways at Cape Tormentin and the island railways, now also owned by the C.N.R., at Borden. Through coaches and wagons are run between the island and the mainland. The "Prince Edward Island" is 285 ft. in length, and has a moulded depth of 32 ft. ; her dead weight, on a draught of 18 ft., is 650 tons. The vessel is so designed as to offer the least possible resistance when forcing its way through ice ; the hull is abnormally strong, and the frames, which are of extra large section, are more closely spaced than usual. For a depth of 6 ft., extending above and below the waterline, the steel plating of the hull is 1 in. thick. and flush throughout ; every constructional detail has been worked out to withstand the ice-pressure.

Many thanks for your help

|

Share this page on Facebook - Share  [email protected] |