|

|

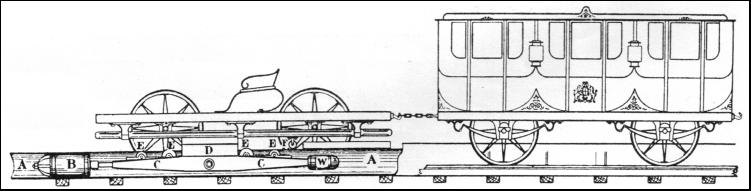

Although it was the locomotive that made the railway - hitherto represented by only a few colliery tramroads - a commercial success, there were among the pioneers men who wondered if trains could not be worked speedily and efficiently without the use of locomotives at all. In the first place, it was thought that locomotives would be unable to climb the hills. Brunel was quite prepared to find that he had to wind trains up the long bank through the Box Tunnel, although he hoped that his broad-gauge engines would develop great power. In the event, they proved equal to the climb, and cables were never used at Box, as they were on some other inclines in the country. The blow-holes which Brunel had sunk from the hill-top into the tunnel were necessary, after all, for ventilation; they helped to clear the smoke which pessimists had said would suffocate the passengers in what was then the longest tunnel in the world. Smoke was the second objection to the locomotive. It may not have been worse than dust on the road, and it certainly was not as bad as the mud, but it the impression that the railway was dirty. It told, to, of travelling fire. Farmers were afraid that their ricks would be set alight by sparks from the passing engines; folk in town feared a like danger to their houses. London sought to keep the locomotive at bay if the railway should come within her bounds. True, she used engines on her first line, the London and Greenwich Railway, part of which was opened late in 1830, but she worked her second line, the Blackwall Railway, which touched the City, by cable. It was even thought necessary, when the Birmingham line was opened for the locomotives to be taken off at Camden and the trains wound into and out of Euston. Winding was an old colliery practice and possibly rather clumsy; and so engineers were soon trying to think of a better way of running a line without locomotives. Although locomotives had shown that they were practicable, they were not altogether popular at a time when those who were interested in the old horse traffic on the road were ready to spread tales against them. There were powers other than steam; both water and air had been successfully employed by man for centuries. Water has never been used to work a railway except in the instance of some cliff lines, which are really lifts, where one car, weighted with a full tank, draws up another with an empty tank. But there was an early proposal to build an elevated line to Brighton, on which trains fitted with sails should be carried along by the wind. Because of the fitfulness of the wind, this would not have been a line on which any sort of timetable could have been kept, and it was never more than a picturesque dream. But the air was to play its part on the railway by providing power through what we should now think of as the third rail. The eighteen-forties, when lines were being built and extended everywhere, saw in London, South Devon, and Ireland, a gallant experiment which was rather grandly called the Atmospheric Railway. There was already the pneumatic tube along which, if the air were drawn out at one end, a piston or carrier was shot by the force of air coming in at the other end. A message in the carrier could be sent speedily by this method. Clegg and Samuda conceived the idea that, if some connexion could be made between the piston in the tube and a train outside it, the piston would draw the train along at least as fast as a locomotive could draw it. This meant that there had to be throughout the whole length of the tube a slot from which a bar could come up to make a coupling with the train. That raised the problem as to how the tube could be kept air-tight, as it should be if it were to work properly.

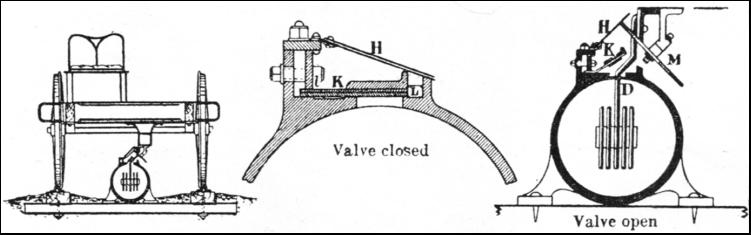

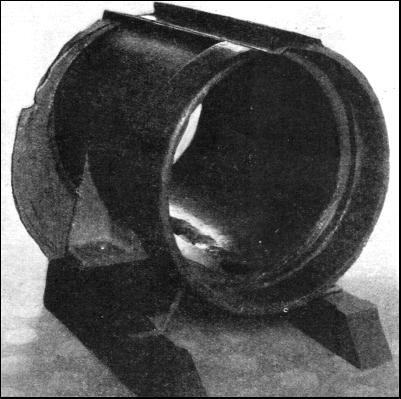

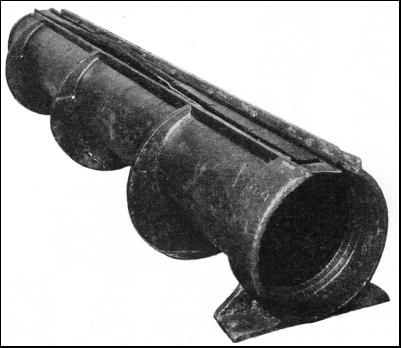

The plan adopted was, perhaps, the only possible one. A leather flap was laid over the slot, and, as the coupling came by, two little wheels running before it raised the flap and so gave passage. Behind the coupling the flap fell back over the slot and closed it. Theoretically, there should have been no leakage; in practice, as was proved later, there was a good deal; and it was that which caused the system to fail. Clegg and Samuda tried out their pipe on a track at Wormwood Scrubbs, which is now part of the West London Railway (London, Midland and Scottish and Great Western Joint) that runs through Addison Road. The trials were made there, perhaps, because at the time there was no other use for the line. They were successful enough to impress Brunel. He had finished the Great Western and the Bristol and Exeter, and was now pushing on with the South Devon Railway. So far he had built an easy line which, although it might give a few long climbs, did not give a really severe one. But beyond Newton Abbot he was faced with difficult country. He had to go up and down over the spurs of Dartmoor to get to Plymouth. There was nothing for it but to make a switchback. Once more he doubted if locomotives could climb the hills. So he decided to use the atmospheric system between Exeter and Plymouth and, perhaps, even in Cornwall. That should give him in each train, as it came to a stiff climb, a reserve of power from a stationary engine which there was no need to build within the narrow limits that had to be considered on a locomotive. While he was building the first section of the South Devon from Exeter to Newton Abbot he laid down the pipeline with the rest of the track. The equipment was not ready when the railway was opened in May, 1846, and locomotives had to be used; but the work was pushed forward, for the public was impatient to see the atmospheric trains. Maybe much had been promised of the smoothness and cleanliness of the system; at any rate, a train without an engine would be a wonder to see and travel in. Trials were begun in February, 1847, but it was not until November that there was a public service, and the locomotives did not disappear altogether until the beginning of 1848. During the trials high speeds had been touched - as much as 70 miles an hour with light trains; and later, when there was full working, it was reported that of 884 trains run 790 had kept time or gained it. But the test of the pipeline on the almost level track beside the estuary of the Exe and under the cliffs of the coast was not the test that Brunel hoped to give it later over the hills when he had to turn inland.

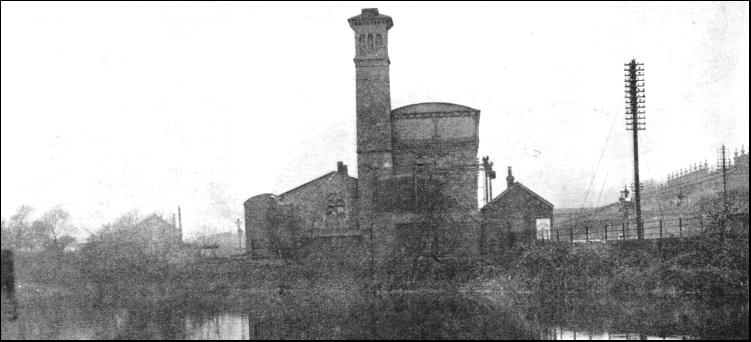

The pumping stations on the South Devon stood three miles apart, and worked in relays. When a train was due in a section the station of that section began to pump out the air, and then ceased to pump when the train had passed. That, at any rate, was how it should have been, but there was no telegraphic communication between the stations; the coming of a train had to be calculated according to the time-table, and sometimes a station began to pump too soon. This lack of co-ordination naturally added to the cost of working, and it seems strange that the South Devon Railway had no telegraph, for the parent line, the Great Western, had it practically from the beginning. What was, perhaps, the first line in use was laid between Paddington and West Drayton and later extended to Slough. Over this line went some now historic telegrams. One in 1844 was a royal message, telling London of the birth of a prince at Windsor. Another in the same year was the first ever sent by the police in the hope of preventing or detecting crime. That was when a large crowd, with many known pickpockets in it, went by train from Paddington to Slough for Montem Day at Eton. The names and descriptions were telegraphed down to Slough, where some of the pickpockets were warned and others arrested as they stepped out of the trains. But the lack of co-ordination was not the only trouble to beset the South Devon Railway. Soon the flap which should have kept the pipe air-tight began to show its weakness. The leather did not stand up to the wear and tear brought about by the passage of the coupling, and the gap had to be freely coated with tallow to keep it pliant and make it fit closely over slot. The tallow had its enemies; the sun melted it and rats ate it. The difficulty of maintaining the flap in good order caused the pipe to become leaky and the running of the trains to be uncertain.

Brunel was loth to abandon the system until he had seen how it would work on the line that he was building, with this in view, beyond Newton Abbot; but, as no better flap than the one in use could be devised, he had to go back to locomotives in the autumn of 1848. He had estimated that there would be a saving of £67,000 in outlay and a yearly saving of £8,000 in working. The South Devon lost between £300,000 and £400,000 on the atmospheric system, and the company, now merged in the Great Western, was left with a line, between Newton Abbot and Plymouth, which was not planned for locomotives. It could not have been made an easy line, but it probably would not have been as heavy as it is if it had not been built before Brunel had lost faith in the project. It was on the line between London Bridge and Croydon that Londoners had whatever thrill there might be in riding on the Atmospheric. On this line the system was adopted mainly because of the prejudice against locomotives in or near London. The inspiration came to the Croydon directors, as it had to Brunel, from the seeming success of the Atmospheric on the little Dublin and Dalkey line in Ireland; but the Croydon line was ready for equipment long before the South Devon. The trains began to run in 1845, but here, as elsewhere, the flap or valve failed, the pipe became leaky, and the trains lost speed and sometimes stopped through lack of power. They could not climb to the summit, and tales are told of how passengers got out to push, and sometimes pushed so hard that the train ran away and left them behind. The Croydon pipe was fifteen inches, in diameter, and the South Devon twenty inches. The flap was the same on both lines, and on both it proved neither weather-proof nor rat-proof. In hot weather the tallow ran, and at all times the rats came for a feast. The atmospheric system was abandoned between London and Croydon in July ,1846, when the Croydon line became the property of the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway. It was a pity that Brunel did not take a lesson from this picture, but he was still wondering how he was to get trains over the Devonshire hills without the assistance of power stations. Little is remembered now of the Atmospheric, but it is interesting to look back upon it as having given the railway its first third rail, or, at least, the equivalent of it. It was the first system that allowed of the transmission of power, otherwise than by a winding drum, to places far away from the engine; and so its power stations were the first in the world. We talk familiarly now of power stations; and the third rail as we think of it, giving electric current to trains, is a commonplace on suburban lines and no longer a novelty on runs to the coast. We did not see the third rail until 1890, when the first section of the City and South London Tube was opened, and that was forty-two years after the Atmospheric was scrapped. Yet, if London had ever made an Underground for goods only, on the lines of the Post Office Tube Railway, it could have been worked pneumatically, for such tubes could have been made airtight enough. What killed the Atmospheric, as Brunel and others sought to use it, was the difficulty of connecting the piston in the tube with the train outside and at the same time preventing leakage. If, however, the railway engineers of the period had not been able to fall back upon such a convenient alternative as the steam locomotive, these grave defects might have been surmounted.

Many thanks for your help

|

Share this page on Facebook - Share  [email protected] |