|

|

THE light railways of Great Britain are among the most interesting of all systems, although, tucked away in odd corners of the country, they are seldom, seen by the majority of the travelling public. Such lines are not only remarkable for the diversity in design of their locomotives and rolling stock, but they also have histories that arc well worth investigation. One of the most interesting of these lines is the Festiniog Railway, the history of which is closely related to that of the slate industry of Wales. The construction of the railway was, in fact, the outcome of a desire on the part of the slate quarry owners to find a reliable way to transport their product to the sea for shipment. Slate had been systematically mined in the district since the middle of the eighteenth century. The carts and horses of the farmers in the neighbourhood were hired for the purpose of taking the slates to boats at tidewater about ten miles distant. Festiniog being at an elevation of 700 ft. above sea-level, and the roads difficult, this method of transport proved inconvenient when the slate quarries increased their output. The point of shipment, being in a shallow estuary, was accessible to boats at spring tides only, and cargoes could be sent but once a fortnight. This drawback, combined with difficulties encountered in securing sufficient horses and carts, rendered it imperative to find some more trustworthy means to reach a harbour available for regular daily shipments. In the year 1810 Mr. William Alexander Madocks had completed, at a cost of £100,000, an extensive land reclamation scheme by building an embankment over a mile long, 100 ft. high, and 30 ft. wide at the top, across what was then a bay near the present town of Portmadoc, which is named after him. This and another embankment two miles long on the west side of the bay, reclaimed thousands of acres of land as far inland as the Pass of Aberglaslyn. This pass is one of the beauty spots of Wales. Through the picturesque narrow defile the Glaslyn torrent rushes on its way to the sea. A modern highway runs side by side with the stream between steep fir-clad cliffs. Mr. Madocks. who was assisted in his work of reclamation by the poet Shelley, had the foresight also to construct docks at Portmadoc, and he improved the port for the accommodation of shipping, to deal with the slate traffic from Festiniog and to ship copper from mines in the neighbourhood of the port.

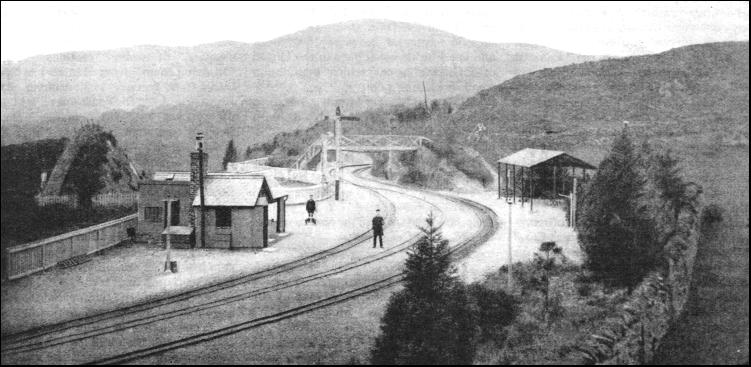

The former residence of Mr. Madocks—Tan-yr-Allt—stands near the village of Tremadoc, where the buildings are arranged in the form of a quadrangle and represent an early attempt at town planning. At the western end of the grounds of Tan-yr-Allt there formerly stood the house occupied by Shelley, and it was here that the poet wrote much of his immortal "Queen Mab." One night in February, 1813, Shelley stated that an attempt had been made on his life at Tan-yr-Allt and he left the neighbourhood. It is said, however, that the supposed attempt to murder the poet was a ruse adopted by local shepherds to drive him away because Shelley, it appears, was in the habit, when walking the mountain-sides, of putting sick or injured sheep out of pain by shooting them with a pistol. Railways were, as yet, not projected, and a turnpike road was built along the embankment to form means of communication between the counties of Merioneth and Caernarvon. With such facilities available, it was only natural that the slate quarry owners should decide to abandon their old methods of shipment. Many plans and suggestions were put forward, but nothing tangible was done until 1831, when Mr. James Spooner surveyed a route for a railway from Festiniog to Portmadoc. The project was adopted, but was turned down by Parliament. As happened on other pioneer railways, strong opposition was encountered from local vested interests, but the Bill was passed in 1832, and the company was incorporated under an Act of William IV, supplemented in 1869 by an Act of Victoria. Construction of a narrow-gauge railway was begun in the early part of 1833, and the line was opened to traffic three years later, being confined to goods only until 1863. Tourists from all over the world go out of their way to travel through the romantic and beautiful scenery traversed by the line. Hundreds of thousands of tons of slates have been and are being carried by it to Portmadoc for shipment to all parts of the world. The length of the railway is 13 miles 62 chains ; in that distance there is a difference of level amounting to 700 ft., the gradients being continuous but varying from 1 in 186 to 1 in 69. The gauge is only 1 ft. 11-1/2 in. The construction of the line was not an easy matter, as it had to be cut for many miles in the form of a ledge out of solid rock some hundreds of feet above the valley. Many ravines had also to be crossed on narrow stone embankments, some as high as 60 ft., and only 10 ft. wide at the top—a seemingly precarious perch even for a light railway. These embankments have, however, stood up to their work for many decades past. Most of the cuttings had to be made through the solid rock and, in addition to these, there are two tunnels, one just above Tan-y-Grisiau, 60 yards long, and the other 750 yards long, between Dduallt and Tan-y-Grisiau. The tunnels are 8 ft. wide and 9 ft. 6 in. high, just large enough to accommodate trains on the single track. The longer tunnel is driven through syenite and the shorter through slate.

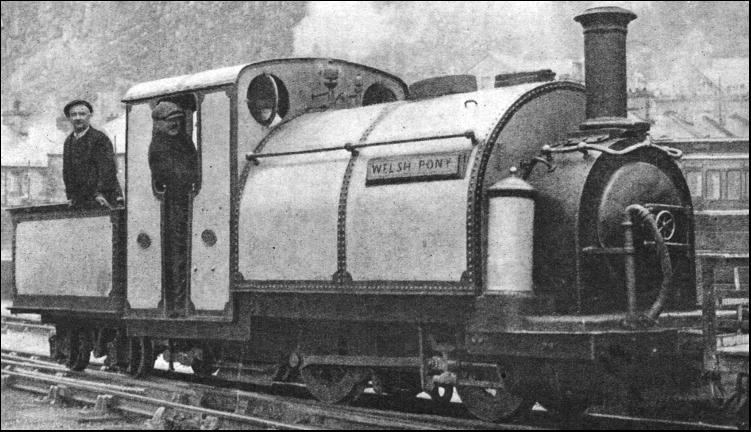

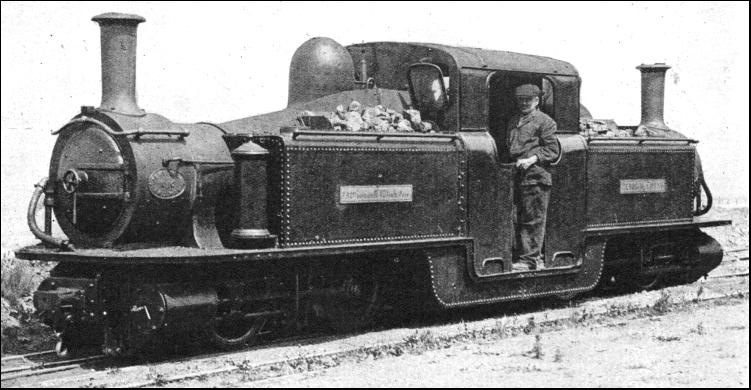

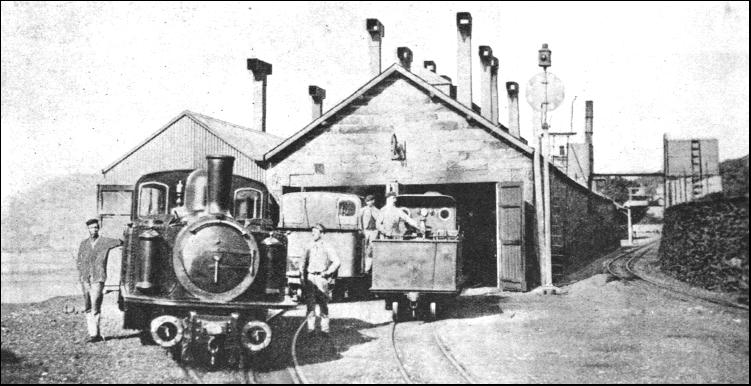

Practically the whole line consists of a series of curves, some of them having a radius of only one chain and three-quarters. The longest radius is eight chains. The experience of negotiating a lengthy curve of short radius, traversing a ledge high up the sheer mountain side, is one that is not easily forgotten, as the elevation of the rail gives the impression of hanging over the side of the abyss. In the early days, at one part of the line, trains were hauled up an incline by means of ropes actuated by a water-wheel fed from a reservoir built for the purpose. On the other side of this height there was another incline, down which the loaded trucks were lowered by gravity. As the loaded trucks went in one direction only, down the line, it was necessary to supply motive power for drawing them up only one incline. On either side the empty trucks were attached to the other ends of the ropes and drawn up as counter-weight. Later, a tunnel was driven underneath the height, and this interesting old part of the line was abandoned. At first, horses were used to draw the trucks, but it was soon discovered that, to cope with the traffic, some other means had to be employed. Because of the narrowness of the gauge and the short radius of the curves, eminent engineers, including Robert Stephenson, were of the opinion that locomotives could not be built to run on the line. But two locomotives were purchased at an early date by the railway company to work the trains. These engines were 0-4-0 tanks with outside cylinders, and weighed 7-1/2 tons each. They were named "The Princess" (No. 1) and "The Prince" (No. 2), and were followed by two similar engines by the same maker, George England. The third engine was named, appropriately enough, the "Mountaineer," and No. 4 was called "Palmerston," no doubt as a compliment to the famous statesman. The last two engines were designed by C. M. Holland. The railway began the carrying of passengers in 1864, but this was in the nature of an experiment, and travellers rode in the trains at their own risk—although they paid nothing for the privilege. The following year, however, regular passenger traffic was introduced on a section of the railway. Two more four-coupled tank engines were put into service in 1867, the "Welsh Pony" and. the "Little Giant," numbered 5 and 6 respectively on the company's locomotive list. A peculiarity of all engines on the Festiniog line is that the iron wheels and tyres are cast in one piece. Usually a steel tyre is shrunk on to the cast iron wheel, but it was found that application of the brakes on descending to Portmadoc caused steel tyres to expand so much that they became loose on the wheels. Increasing traffic necessitated further additions to engine stock, and in 1869 the company purchased a "Fairlie" patent "double-ended" locomotive. This was the seventh engine acquired by the line, and was named "Little Wonder." Three years later another "Fairlie" locomotive. No. 8, "James Spooner," was built for the railway by the Avonside Engine Co.

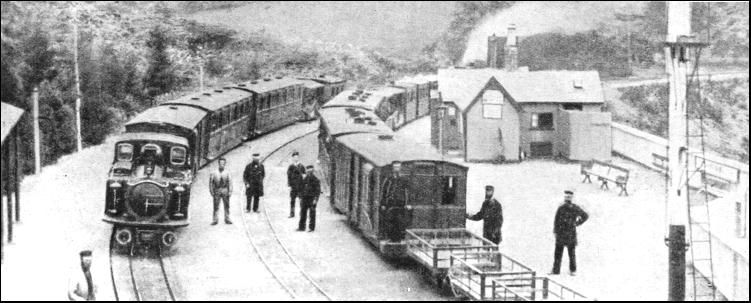

A tank engine. No. 9, "Taliesin," having the 0-4-4 wheel arrangement, was built at Boston Lodge Works in 1885, and was named "Livingston Thompson." Twenty years later, in 1905, this engine, No. 11, was renumbered 3 to fill the gap occasioned by the loss of the "Mountaineer" in 1879. The speed of the trains was originally limited to a maximum of twelve miles an hour, but after the advent of the "Fairlie" engines, this was increased to thirty miles an hour. The runs from the higher terminus at Blaenau Festiniog to Portmadoc on the sea, and vice versa, take about one hour in either direction, there being eight intermediate stops at stations and "halts" along the line, and many curves to be negotiated at low speed. The line, which is a single track, is worked on the staff and block system. It will be appreciated that where a single line is used by a number of trains running in either direction, special precautions have to be taken to obviate head-on collisions. Passing loops are, of course, provided to enable up and down trains to pass one another at convenient places on the line. These are similar to the loops used on single-line suburban tramways. A peculiar feature of the railway is that the trains keep to the left when passing at the loops. This claims to be the only line in Britain where the practice obtains. It is usual for trains to pass on the right. The "staff" system of train control provides that the driver of a train about to enter a section of single-line track must, before proceeding, possess himself of a "token," usually a wooden or metal staff about a foot long. Formerly, only one staff was provided for each section, so that no two engine drivers could receive authority to run on the single line at one time. The staff was usually fitted with a large wire ring at one end to facilitate exchange at speed between the respective drivers of up and down trains when passing at the loops.

A driver entering the section would lean from his cab and catch the ring of the staff extended to him by the driver of the train leaving the section of single line. This system is still used on some single-track railways, but an interesting development followed on the necessity on some lines of running a number of trains successively one way before the passage of a train in the opposite direction. The difficulty was overcome by providing at each passing loop an instrument containing a number of staffs locked in a frame by electrical means. The instruments are fitted with an indicator showing whether the line ahead is clear ; they are fitted also with a telephone. The driver of a train entering the single-line section glances at the indicator. If it is set to, "line clear" he is able to withdraw a staff from the locking frame and proceed. His action in withdrawing the staff sets his own, and the distant passing loop instrument, at "train on line," and prevents the withdrawal of a staff from either locking frame, as they are electrically interconnected. When the driver reaches the end of the section, he places the staff in the instrument at the passing loop. This action unlocks the frames at both ends of the section, ready for further use. It will be noted that only one staff can be used on the section at one time.

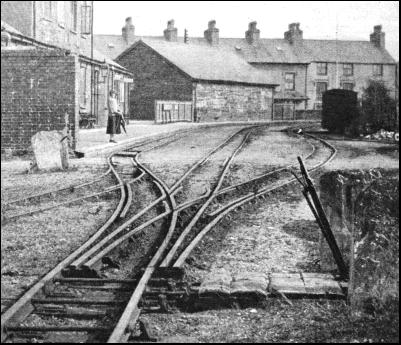

Telegraphic communication exists between all stations and signal boxes. Although on a small scale, the line has engine sheds, constructing and repairing shops, crossings, points, and signals in the same way as the standard gauge railways. There are many quaint and unusual sights on this railway, such as the old-type signals, now derelict, but still standing here and there along the line. The first train in either direction is styled the "Parliamentary." The waiting rooms once exhibited (and probably still do) interesting notices, one prohibiting smoking on the station premises, and another warning that tickets at intermediate stations would be issued only when the train was in sight. There are no platforms at the stations, and the carriage doors are always locked, a necessary precaution not only against possible accidents to passengers, but also against damage to rolling-stock, the clearance between the side of the train and the rock along the line and in tunnels being less than the width of a carriage door.

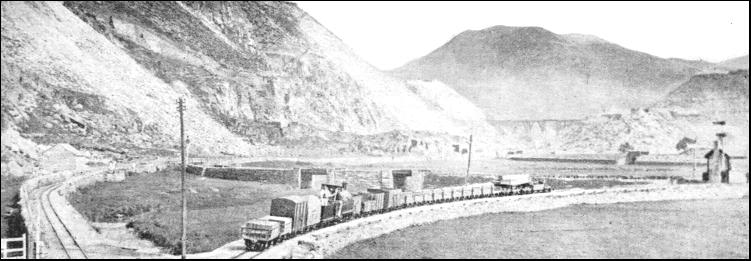

An interesting sight is a train of trucks loaded with slates, sometimes as many as fifty or sixty, travelling down the line without an engine. These trains are controlled by hand brakes on trucks at intervals along the train, which are operated by brakesmen who run along the tops of the trucks to put them on or take them off according to the gradient. A long line of empty trucks is brought up the line behind the coaches of passenger trains. Central buffer couplings are used throughout, and the maximum weight of a train is about 190 tons. Locomotives Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 were still in use in 1935 for goods traffic, not in their original form, but reconstructed with saddle tanks. Over seventy years of service is a remarkable achievement. The Festiniog Railway claims to be the first narrow-gauge railway in the world. It aroused such interest that in 1870 a Royal Commission, presided over by the Duke of Sutherland and attended by representatives of many foreign countries, inquired into its working and efficiency. So satisfactory was the report of this Commission that before ten years had elapsed well over 10,000 miles of narrow-gauge railways had been constructed in India and other countries. Portmadoc, the coastal terminus of the Festiniog Railway, is also on a branch, formerly of the Cambrian Railways and now of the Great Western Railway, which runs along the coast of Merionethshire and Caernarvonshire from Barmouth Junction to Afon Wen and Pwllheli. Another line, the narrow-gauge Welsh Highland Railway, used to serve Portmadoc regularly until quite recently. Its tracks extend from Portmadoc past the delightful village of Beddgelert to Dinas Junction, on a branch of the L.M.S. from Bangor to Afon Wen via Caernarvon. The Welsh Highland Railway has a mileage of twenty-seven, and owns three locomotives, ten carriages, and 104 wagons. The gauge is the same as that of the Festiniog Railway.

Many thanks for your help

|

Share this page on Facebook - Share  [email protected] |