|

|

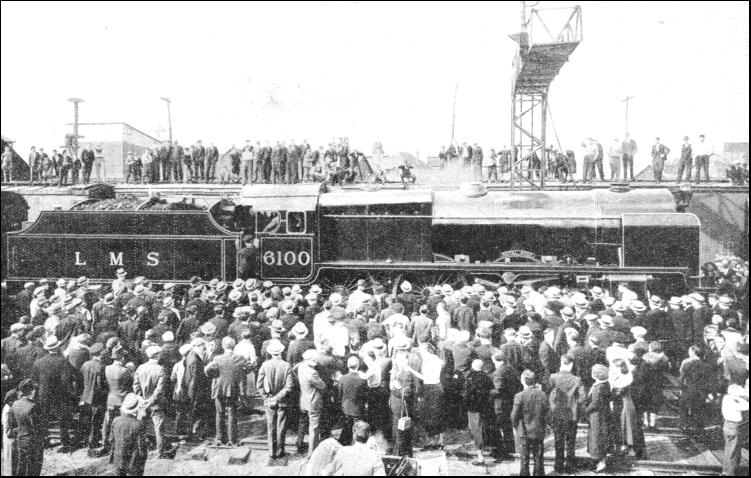

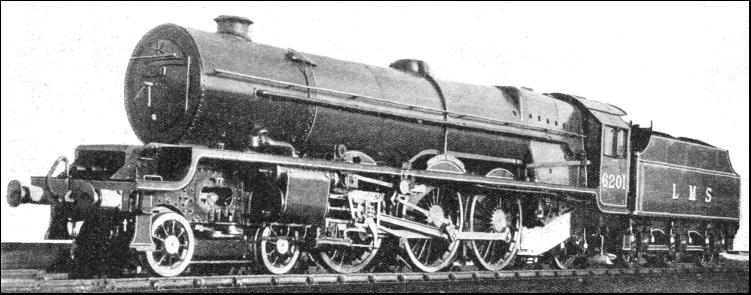

THE "Royal Scot" is a train with a tradition that began nearly seventy-three years ago. It was on June 1, 1862, at 10 a.m., that the great express first left its southern terminus for Scotland, and ever since it has drawn out of London at the same hour. In those seventy-three years there have been great changes on and around the railway ; the "Royal Scot" has survived them all. It has been developed in every detail, improved and speeded up again and again, but it still remains the train with a tradition. To-day, on the stroke of 10, it will pull out for its far-distant destination, with a weight of at least 450 tons behind the engine. Right across the Midlands, through the Lake District and over the Scottish Border it will go, the passengers comfortably unconscious of the difficulties of the route. And to-night it will slow gently to a standstill, on time, 400 miles away ! The first of the specially-designed engines to do this long-distance run, without change, from Euston to Glasgow was No. 6200, the " Princess Royal," built in 1933. At other times engines of the "Royal Scot" type are used, and are changed at Carlisle. It was No. 6100, "Royal Scot," that toured the Dominion of Canada and the United States of America in 1933, covering under her own steam over 11,000 miles on the railroads of the North American Continent—the first time that a complete express train had been sent across the Atlantic, to be welcomed, cheered and fâted by the English-speaking peoples of the New World.

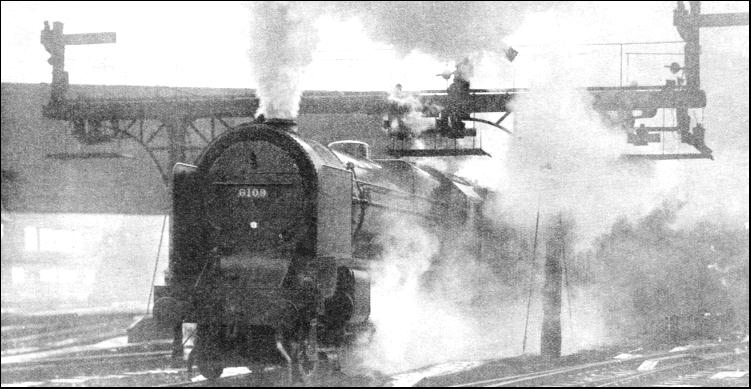

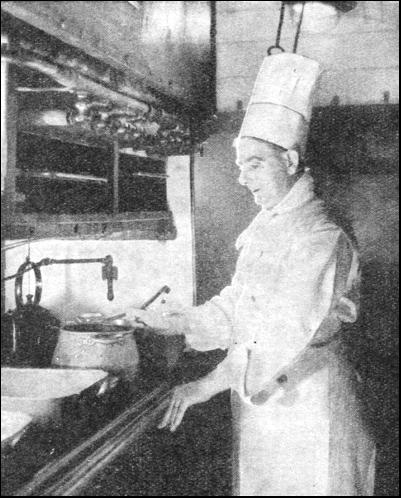

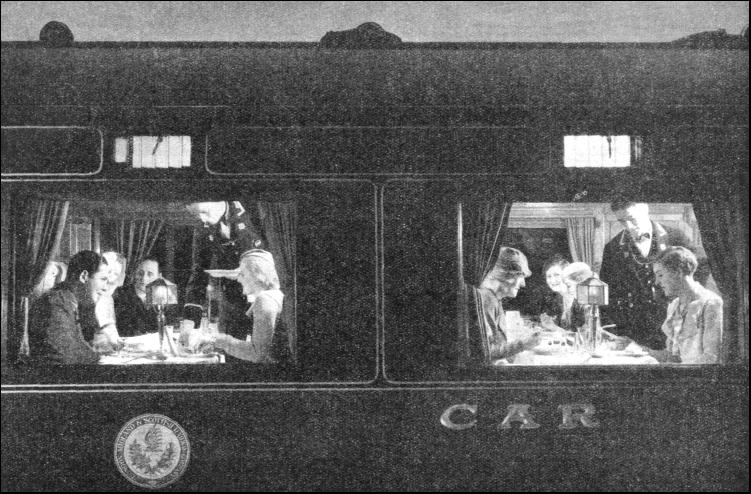

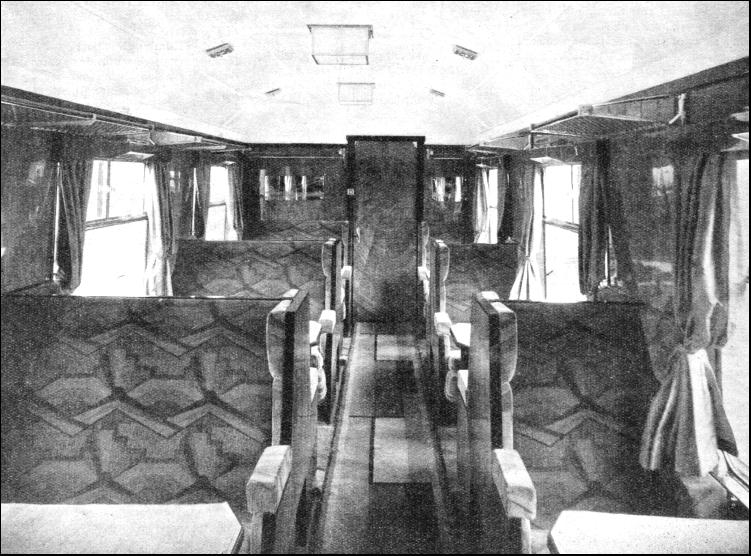

The engine makes an impressive sight as it stands at the Number 13 departure platform at Euston, ready for the run to Scotland. The engine crew, who will have been busy on their charge for an hour and a half or so before the train is due to leave, will be checking every detail of the locomotive's equipment, since theirs will be the responsibility until they hand over to a relief crew at Carlisle, almost 300 miles away. Before the train reaches this point the fireman will have to feed, single-handed, at least five tons of coal into the ravenous furnace ! This is highly-skilled work, too, since the coal from the tender must be laid evenly over the fire-grate—left, right, and centre—to maintain a fire without "holes" through which air would rush with a cooling effect on the firebox. In addition to the exacting physical feat of feeding tons of coal to a fire, the fireman watches the boiler water-supply. and when over the troughs between the rails he lowers the tender-scoop, to replenish the tank. There are some hundreds of signals between London and Carlisle, and the driver must be on the look-out for each in turn, ready to moderate his speed at a moment's notice should the signal indicate that the line ahead is not clear. Apart from the locomotive, the train itself lias many points of interest. It is made up into three sections, for Glasgow, Edinburgh and Aberdeen respectively, and a feature of special convenience is the design of the windows. They are unusually large, and set very low, so that the passenger has every opportunity of appreciating in comfort the magnificent scenery through which the train passes. Comfort, in fact, has been studied at every point, with such complete success that it is common to hear the alighting passengers remark that their long journey was not merely comfortable, but was also restful—a striking tribute to the train itself and to the well-laid permanent way. The train in normal circumstances, comprises 15 coaches of different types, the total length, including engine, being about 230 yards. It can accommodate approximately 290 passengers, who, with their luggage, represent a mere four per cent of the total weight of the train—say 25 tons of passengers and luggage, against the 585 tons of the locomotive and coaches. In a few hours it must be transported across a dozen counties, and be raised twice in succession to a height of about 1,000 ft. above sea level, both south and north of the Scottish border. The route is a continuously fascinating succession of changing scenes. Crossing the rivers, and driven through diverse countryside, it provides us not only with a panorama of life in Britain today, but also with unexpected glimpses of the lives of our forefathers. Natural beauty of scenery, engineering triumphs, historic castles, hamlets, cities, Roman remains—they fly past the windows in a pageant, displaying Britain and her history to the traveller. We cross the Roman roads and pass the old battlefields ; we see the very structure of our land laid bare in the marked changes of geological strata, as the train roars steadily along the great steel roads. Ours is the route that history has followed—a road of post-chaise and pack-horse riders, that in their distant day had found a way already trodden by medieval marchers, and founded upon the Roman roads.

So varied are the associations of the route that to comment upon them all would be to write a history. But a few notes on chance-chosen points of interest seen from the windows of the "Royal Scot" will serve to show the romance that still lingers along this historic highway. Even as we pull out from Euston, powerfully breasting the steep bank up to Camden, we have a reminder of railway history, for in the early days of steam locomotion that slope was considered quite impassable, and the trains were hauled up to Camden by cable. Soon after leaving London we see Harrow (on the left as we face northwards to the engine), rising picturesquely from the Middlesex meadows, surmounted by two spires. The smaller of these spires belongs to tlie famous Harrow School Chapel. The other spire is that of Harrow's Parish Church, the history of which goes back to the days of William the Conqueror, when it was founded by Archbishop Lanfranc. There is a curious railway relic in Harrow churchyard, in the form of an epitaph to one Thomas. Port. He was probably the first engine-driver to lose his life on the railway, and a portentous poem still records the details of this tragedy of nearly one hundred years ago. Soon after passing Harrow the train leaves Middlesex for Hertfordshire, the boundary lying between the Hatch End and the Carpenders Park stations. A white stone pillar will be seen on the left-hand side, at this spot, but even those with full leisure to examine it are generally unaware of its significance. It bears a cryptic inscription, "Act 24 & 25 Vict. Cap. 42," and refers to an old Act of Parliament which decreed that any wine, coal or cinders imported across the boundary were subject to a duty by the Corporation of London. The proceeds, which were considerable, were allocated to the Bridge-Building Fund, from which the money was derived for the construction of the Tower Bridge, London. Soon after passing Watford Station the train enters a tunnel over a mile long. This tunnel affords a striking instance of the difficulties of the railway pioneers. They had to face opposition from the influential landowners, who feared that the railway would adversely affect their properties. North of Watford the railway had to pass the great adjoining estates of the Earls of Essex and of Clarendon. To overcome the objections raised, the Watford Tunnel was designed to carry the railway line out of sight of the great parks, and although it involved the company in heavy expense it served its purpose and solved the problem of access from London to the industrial areas of the north-west. Many difficulties now almost forgotten must have confronted those pioneers of the railway, and it is said that when Robert Stephenson was surveying the line he walked along it the whole distance from Birmingham to London more than twenty times—a good example of the early fortitude that enabled the traveller of to-day to be transported so swiftly and comfortably. After emerging from the Watford Tunnel the railway line runs into a valley of the Chilterns through which flows the Grand Junction Canal—at one time a serious rival of the railway. This canal runs more or less alongside the railway almost as far as Rugby King's Langley is the next station, and then we come to Boxmoor, approaching it through a cutting and by an embankment, under which the road goes, near Boxmoor Station. As this road winds round to the left of the line it passes in about a quarter of a mile an old farmhouse, and between this and the line is an interesting memorial of the bad old days of travel, when highway robbery was rife.

Near a clump of chestnut trees are two stones in a field, which mark the grave of a desperado named Bob Snooks, who carried out a daring and successful mail robbery in 1800. He was captured and sentenced to hang in chains for his crime, and at the execution he made a pitiable appeal that his body should be buried decently in a coffin, instead of being exposed on the highway. He died vainly offering his gold watch to any spectator who would undertake the task, but eventually the request was posthumously acceeded to, and the mortal remains of Bob Snooks now rest in a coffin paid for by local subscription. Just before we reach the next station, Berkhamsted, on the other side of the route we see traces of tlie spacious Middle Ages, for within a few yards of the line is all that is left of Berkhamsted Castle. It was a great fortress in William the Conqueror's day, and was closely associated with the boyhood of the Black Prince. The observant traveller may have noticed that the line has for some miles been gradually climbing, and there have been occasional indications of the chalky nature of the Chiltern Hills across which it is passing. The summit of the grade is reached at Tring Station, and the descent from there is notable for the quick change of scenery which takes place when the gentle slopes of the southern approach give place to the more wild and weather-beaten northern side of the hills. Soon after leaving Tring we pass under three bridges in quick succession, and then we come to a fourth, which lies on the boundary between Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire. Over this bridge runs the Icknield Way, a direct link with Roman Britain, for undoubtedly the old road was greatly used by Caesar's legionaries. The road itself, however, existed long before Caesar's hosts came to conquer Britain, and still winds across the downs towards Oxford.

As we pass into Buckinghamshire it is interesting to note that although we have travelled only a little more than thirty miles from London, the historical associations evoked along the route have already extended to pre-Roman times. They are but fleeting glimpses we can obtain, but they serve to show that the way along which we are travelling is a well-trodden one, and the traces of our forefathers are far more closely distributed along it than is generally known. When the railway engineers surveyed the lines, and overcame the obstacles, they took from the traveller a burden he had borne throughout history. In the past, to breast the hills and cross the valleys meant a succession of adventures, which no wayfarer could escape, until the railway came. But once this revolutionary change had been wrought, the gradients scientifically surmounted, and the line fenced off from the surrounding countryside, it became possible for the first time in history to travel across wide stretches of land in speed, in safety and in comfort. After passing Tring and descending the northern slope of the Chiltern Hills, the first considerable town on the route of the "Royal Scot" is Leighton Buzzard. The town itself (though not the station) is in Bedfordshire, and half a mile beyond it is Linslade Tunnel, from which the traveller emerges to view an interestingly changed scene. To his right is a pine-and-heather-clad hill, of red sandstone, noteworthy to the student of geology because the sandstone is an older formation than the chalk of the Chilterns. There are many historic relics along this part of the line. One of them is Bradwell Priory, the remains of which are to be seen on the left just before we cross the Grand Junction Canal at the approach to Wolverton Station. This priory once belonged to Cardinal Wolsey—a present from his royal master, Henry VIII. The next station is Castlethorpe, so called from a Norman edifice, on the site of which the station now stands. Three or four miles farther on we cross the county border and leave Buckinghamshire for Northamptonshire.

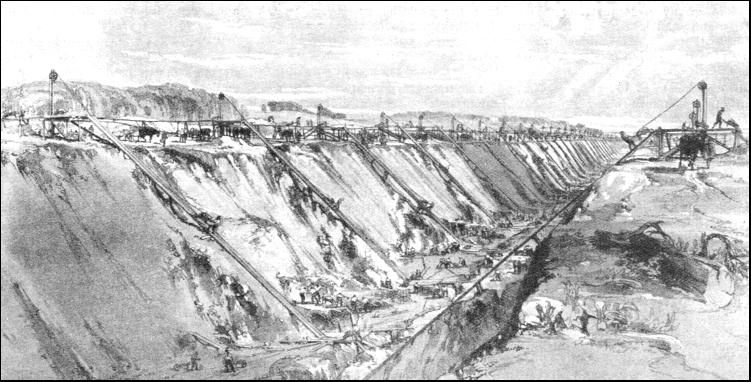

The first station here is Roade, sixty miles from London, and the "Royal Scot" has taken but little more than an hour to reach it, despite the climb over the Chilterns. Just after passing the station the train enters a cutting, one and a half miles long, and with a depth in one place of 70 feet. To construct it was a very considerable engineering feat, which ruined the contractor who first undertook the task, and gave the railway pioneers long anxiety and enormous expense. The cutting had to be made at first through rock (which at this point is rich in fossils) resting upon a layer of clay, supported in turn by a waterlogged bed of shale. Grave problems of drainage were involved, and were eventually solved by powerful steam pumps, while huge brick walls had to be constructed to keep the sides of the cutting from falling in. After leaving this cutting the line passes through Blisworth Station, and on to Weedon. Just before reaching Weedon Station the tall wireless masts of the Daventry broadcasting station come into view. This is the centre of the British Empire radio service, and Daventry is engaged almost continuously in broadcasting to South Africa, India, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and other parts of the Empire. Soon after passing the next station, Welton, the line enters the famous Kilsby Tunnel, which is 1 mile 666 yards long. It is memorable because of the enormous difficulty it gave to George Stephenson and other pioneers who drove the railway through it. This tunnel, although estimated to cost £100,000, required more than three times that amount to finish it. Water was the cause of the trouble, the workmen having tapped an unsuspected quicksand when the work was well advanced. It was thought that the whole project would have to be abandoned, but George Stephenson decided on pumping, and powerful engines for the purpose were installed. For eight months they worked continuously, removing two thousand gallons of water a minute. Huge round towers at the tops of the shafts still bear witness to the gigantic labours undertaken by the pioneers at this spot to cleave a way for the railroad.

Their tunnelling may be said to have been carried out through the very backbone of England, since the limestone ridge at Kilsby is a watershed, separating by a narrow strip of land the water which drains westward, into the Severn system, from that which flows eastward into the North Sea. Emerging from the Kilsby Tunnel we leave Northamptonshire (after the second bridge across the line) and enter Warwickshire. To the right can soon be seen a cluster of wireless masts, specially noteworthy because they are part of the world's most powerful wireless transmitting station, at Rugby. Here is the European end of the transatlantic telephone system, and through Rugby it is possible for any telephone subscriber in this country to speak to almost any other telephone subscriber in the world. Rugby is of great importance as a junction, since lines radiate east and west from this point, affording connexion with all parts of England. For this reason the "Royal Scot" is scheduled to call here, except in the height of summer. Between Rugby and Nuneaton, nearly fifteen miles away, the line passes right through the heart of the country made famous by George Eliot's novels. Within a few miles stands the original "Mill on the Floss," and, from the panorama of the train windows lovers of literature will be able to appreciate how well the character of this countryside was described by the novelist. Warwickshire, as seen from the "Royal Scot," is an interesting county, and there are many evidences that we are passing from the southern into more industrialized areas. Just past Nuneaton we have a glimpse of Hartshill, where there are extensive granite quarries, and the next station, Atherstone, is a centre of the felt-hat industry. Along this part of the route we get our first glimpses of coal-mines, but the predominant note of the countryside remains a pleasantly rural one—beautiful park-like open country, with old houses and ancient churches tucked away among the trees. We enter Staffordshire at Tamworth ; and Lichfield, 116-1/4 miles from London, is passed just after 12 o'clock. It has many interesting associations, not the least among them being that it was the birthplace of Dr. Johnson, the great man of letters. After passing Stafford, of which town a good general view is afforded, the railway runs through Great Bridgeford Station. Just past it a half-timbered old-world cottage stands close to the line (on the right), with a stream meandering past. This cottage was Izaak Walton's home, and the stream is his beloved Shawford Brook, which he made known to every "complete angler."

After climbing up a gradual gradient to the summit at Whitmore, the railway descends slowly to the level of the Cheshire Plain, that county being entered between Madeley and Betley Road. To the right after passing the latter is a distant view of the Potteries, and three or four miles farther on, just before entering Crewe, are the famous Basford Hall goods sidings containing over 100 miles of track. Crewe is reached before 1 p.m., and as the distance from London is 158 miles, our average speed from first start to stop has been well over 50 miles per hour. At Crewe we may be said to leave the Midlands and enter the North Country, and there are soon to be seen evidences of the Cheshire salt fields and of the many other industries centred in the county. The Manchester Ship Canal is crossed by the line at a height sufficient to allow ships' masts to clear the bridge, and soon after passing over the canal we cross the River Mersey into Lancashire, and run through Warrington. Between here and Wigan there are many signs of the Lancashire coalfield, and in general the county is obviously a highly industrialized one, though it also has an abundance of historical associations. Lancaster itself has a fine church and castle. A dramatic change of scenery is next afforded by our coming out on to the seashore of Morecambe Bay. Across the waters, in the distance, is seen the great rampart of the mountains of Westmorland, through which the railway has now to find its way. The climb begins beyond Carnforth, and in the course of the next 32 miles the line has to climb to an altitude of 915 ft. on Shap Summit. Americans who travel in the "Royal Scot" will be specially interested in Warton Church tower, which is to be seen on the left almost immediately after passing Carnforth Station. It was built by one of George Washington's ancestors in the year 1483. Between Carnforth and the next station (Burton and Holme) we cross the Lancashire boundary into Westmorland, and soon after come within sight of the first of the Borderland fortresses. Beautiful panoramic views of the Lakeland hills are now obtained from the train, and after passing Tebay Station the line enters upon the final stage of the climb to Shap—a gradient of 1 in 75, four miles long, and well known to railwaymen on account of its effect on record-breaking runs. The line runs right through a Stone Age circle just before reaching Shap Station, and about ten miles farther is the old border stronghold, Yanwath Hall. We are now approaching Carlisle, where the "Royal Scot" is due at 3.44, and after a five-minutes halt at the Border City the train pushes on, to cross the Sark into Scotland just beyond Gretna Station. Twenty miles over the border is a station-name that will conjure up many literary associations—Ecclefechan, the birthplace of Thomas Carlyle. Once again high hills lie ahead. The gradient from Beattock Station to Beattock Summit, ten miles on end, averages between 1 in 69 and 1 in 88. Between Beattock and Elvanfoot the "Royal Scot" crosses the county border from Dumfriesshire into Lanarkshire, and we run over this historic county to Symington, where the "Royal Scot" stops in order that the Edinburgh portion may be detached from the rear. The Glasgow portion is the first away, and, running on through Carstairs, it follows the valley of the Clyde, through the coal-mining districts of Lanarkshire, and past the great steel works of Motherwell and Newton, until it crosses the Clyde for the last time by a bridge carrying a score of railway tracks, and enters the handsome Central Station in Glasgow. The time is 5.55 p.m., and the train has been on its journey for 7 hours 55 minutes. During the height of the summer season the Rugby and Crewe stops are omitted, and Carlisle, 299 miles from Euston, is the only stop made south of the Border. Throughout the year, however, the up "Royal Scot" runs without a stop from Carlisle to Euston, and for nine months in the year this is the longest regular non-stop railway run made in any part of the world. The Edinburgh portion, leaving Symington five minutes after the Glasgow portion, bears sharply to the right at Strawfrank Junction, immediately before Carstairs, and enters the county of Edinburgh between Auchengray and Cobbinshaw. All the way to the Scottish capital the country is endowed with beautiful scenery and interspersed with glimpses that recall the romance of the past. Finally we glide into Princes Street, Edinburgh, at 6 p.m., and fitly end our journey in one of Europe's most beautiful cities.

|