|

HOME

BATTLE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

COPYRIGHT, 1905 From: Thomas J. Kirkland and Robert M. Kennedy, Historic Camden, Part One, Colonial and Revolutionary (Columbia, S.C.: The State Co., 1905). pp.146-179.

CHAPTER VI.THE BATTLE OF CAMDEN. This, to the Americans, the most disastrous field of the Revolution, bears the name of Camden, though situated eight miles north of the town. It has also, to distinguish its location more exactly, been termed the battle of "Sanders Creek," or more properly still "Gum Swamp."[1] It occurred, actually, about a mile north of Gum Swamp, a tributary of Sanders Creek, and some three miles north of the latter stream. The term "Swamp" might give a false impression to one not acquainted with the ground itself, which, though almost completely inclosed by marshy streams, is well elevated above them, and afforded an ample arena of high,, dry land for the troops engaged. The American forces in Charleston under Lincoln, closely beset by the British from February to May, 1780, sent urgent appeals to Congress for succor. In response to these calls, a detachment of Continentals, two Maryland brigades, by license so termed, and a Delaware regiment, on May 16th started to their relief from Morris- town, N. J., under command of Baron DeKalb, marched to Elk River, at head of Chesapeake Bay, and from there took passage by boat to Petersburg, Va. Thence they resumed the march overland for Charleston, via the Camden route. The numbers of this detachment have been stated by most American authorities as 1,400, and by the British

as 2,000, the latter being, as will be discussed hereafter, more likely correct. It was July 6th when they reached Wilcox's Mill, on Deep River, near the center of North Carolina. Their progress had been painfully slow, owing to the lack of supplies, and Charleston had fallen weeks before, on May 12th. Further advance seemed deterred by the prospect of starvation in the lower districts of North Carolina, where the conflicts of Whig, and Tory, nowhere else so bitter, had devastated the country. Old crops had been exhausted, the new still green and scanty enough, and the settlements sparse. At this point, therefore, about one hundred and twenty-five miles northeast of Camden, DeKalb halted and rested for three weeks, barely managing to subsist the troops. Here on July 25th Gen. Horatio Gates arrived in camp, having been sent by Congress to supersede DeKalb and assume chief command in the South, now the main theater of the war. The victor of Saratoga, still in high prestige, was hailed with welcome and salutes from the small park of artillery. Of handsome person, prepossessing address, and military experience, at the age of fifty-two it may well have been assumed that his was no mushroom reputation. With the halo of Stillwater, Behmus Heights and Saratoga about his name, he had come now to deliver the prostrate South. In him was none of the Fabius, and he proposed to meet the enemy at once and by the shortest route. Gen. Charles Lee, whom he had visited while on his way down through Virginia, doubtless detected in him symptoms of undue complacency, to be inferred from his parting monition: "Beware lest you exchange your Northern laurels for Southern willows." Prophetic words. Indeed, the fault of his character, vainglory, was

about to yield bitter fruit. On his journey south he had also visited in Winchester, Va., General Morgan, who had been his best officer at Saratoga. Col. Henry Lee informs us that General Gates tried in vain to induce Morgan to accompany him into the Southern campaign about to open. Morgan was still offended at Gates's ungenerous omission of his name from the report of Saratoga, and resentful of his machinations against Washington. He promised, however, to come on later. As it was he did not arrive until after the army had been routed at Camden. Had he been there we may well believe the result would have been glorious. He did come in time to win the brilliant victory at Cowpens, to which the British historian Stedman attributes the loss of America. The small force which greeted General Gates was in destitute condition. His advent, however, raised their spirits mightily. Dalliance may not be laid to his charge, but rather precipitancy, for he at once issued orders for the army to be ready to march on a moment's notice. He decided to proceed by the direct eastern route to Camden. It has been said that DeKalb protested in favor of the longer western circuit by way of Charlotte, where the country was more plentiful and friendly. The rejection of this advice is one of the long catalogue of errors laid to Gates by the critics. It may be remarked in extenuation, however, that General Greene, when similarly situated the following year after the Battle of Guilford, adopted the very same route, to Camden. Col. Otho Williams, who was Gates's adjutant, informs us, in his very interesting "Narrative," that he also presumed to expostulate with his general at the course he was about to adopt, and spoke in favor of that by way of Charlotte. Gates rebuffed him by saying he would

confer with the general officers when the army halted at noon. Williams adds: "Whether any conference took place or not, the writer does not know." Later in the journey, however, General Gates explained to Williams that he had felt compelled to take that line of march in order to form a junction with General Caswell, who, with the only other considerable body of troops, the North Carolina militia, was in the neighborhood of Cheraw, in danger of falling a prey to the corps of British regulars there posted. General Gates further said that Caswell "had evaded every order which had been sent him, as well by Baron DeKalb as by himself, to form a junction of the militia with the regular forces; that probably he contemplated some enterprise to distinguish himself and gratify his ambition, 'which,' said he, I should not be sorry to see checked by a rap over the knuckles, if it were not that the militia would disperse, and leave this handful of brave men without even nominal assistance.' " Williams adds, however, that Caswell's reputation stood high as a patriot and gentleman. Again Gates has been much blamed for neglecting an offer of Colonels Washington and White, to recruit a corps of cavalry from his ranks. He seemed to set no store by cavalry. In the rugged hills of Saratoga he had won without cavalry, where they could not operate, but would have no doubt been of great service in the sandy plains about to be traversed. His only force of that sort consisted of a small body of sixty horsemen, composed, Colonel Lee tells us, of foreigners and deserters, commanded by Colonel Armand, a Frenchman (Marquis de la Rouerie), whom, however, Washington has commended as a very gallant and excellent officer. The march from Wilcox's Mill began July 27th. On August 3d they crossed the Peedee in bateaux at Mask's Ferry. Here Colonel Porterfield, an officer of great

merit, joined them with a detachment of 100 Virginians. On August 6th the borders of South Carolina were reached, and here General Gates indited a proclamation, in rather turgid style, of which the following is a paragraph:

Moultrie says that this manifesto was placed in the hands of Francis Marion, who had come into Gates's camp with his "Ragged Regiment," to be disseminated through the State. This as yet unfamed hero, with his tattered troop, were so derided in the camp, that Gates concluded the best use of them was to send them back into their swamps, as distributors of his proclamation. We could wish he might have discerned the merits of this invincible little colonel. He might have saved the day on that fatal 16th. Williams in his "Narrative" says: "Colonel Marion had been with the army a few days, attended by a very

few followers, distinguished by their small leather caps and wretchedness of their attire. Their number did not exceed twenty men and boys, some white, some black, and all mounted, but most of them miserably equipped. Their appearance was in fact so burlesque that it was with difficulty the diversion of the regular soldiery was restrained by the officers, and the general himself was glad of an opportunity of detaching Colonel Marion, at his own instance, toward the interior of South Carolina." On August 7th the army came up with General Caswell and his brigade of North Carolinians, fifteen miles east of Lynches Creek. In his camp they found a welcome supply of provisions and some wine. In the march to this point they had suffered sore distress. The two weeks' tramp had been a severe ordeal, through pine barrens, "sufficient," in the picturesque words of Weems, "to have starved a forlorn hope of caterpillars. What had we to expect," he continues, "in such a miserable country, where many a family went without dinner, unless the father could knock down a squirrel in the woods, or pick up a terrapin in the swamps?" He tells how the army, when they chanced to strike a patch of "roasting-ear" corn or an orchard, would rush in and devour it like a herd of hungry boars. Of flour there was none in camp, and some of the officers would use hair powder (those were days of wigs and perukes) to thicken their soup. On such diet it is a marvel they could survive, not to say march. Colonel Williams says the General and officers shared the hardships to the full extent with the privates. With the united force Gates pushed right on to Lynches Creek, about twenty miles northeast of Camden, not far above Hough's Bridge. On the opposite side he found Lord Rawdon, strongly posted with three

regiments. Rawdon had moved up to this point from Camden, and was here joined by the Seventy-first Regiment from Cheraw, under Major McArthur. Here skirmishes ensued, but the creek banks being steep, muddy and slippery, and the swamp wide, Gates determined not to attack in front, remarking that to do so would be "taking the bull by the horns." After waiting a day or two he moved up the creek and crossed above, whereupon Rawdon fell back near Camden, camping in Log Town. It would have perhaps been the true policy for Gates to have pursued right on after him and forced a fight. But he considered it more prudent, his troops being probably still exhausted, to await a junction with General Sumter, who was in the direction of Charlotte, and with a body of Virginians in the same quarter. With this object in view he moved across to Colonel Rugeley's, then called Clermont,[2] thirteen miles due north of Camden. Here he took post on the morning of August 13th. Colonel Williams states that the army while at Lynches Creek was encumbered with a great multitude of women and children, with immense amount of baggage. To get rid of these an escort under Major Dean was formed, with wagons in which most of the women were sent off to Charlotte, but many remained behind to share the fate of the camp and witness the harrowing result of the battle. On the 14th General Stevens arrived at Rugeley with 700 Virginians. Shortly after General Sumter came up, and to him General Gates detached 100 of the Maryland regulars and 400 North Carolina militia under Colonel Woolford. These raised Sumter's force to 800,

with which he was ordered by Gates to proceed down the western bank of the Wateree, to capture the British fortified post opposite Camden, known as Cary's Fort,[3] commanded by Col. James Cary, and to cut off the enemy's supplies and reinforcements coming that way. This mission Sumter accomplished with great address and success. On the 15th he reports to General Gates that he had surprised the British post at Cary's Fort, killing seven and capturing thirty. He also intercepted a number of wagons coming in with supplies from Ninety-Six, and seventy recruits. The American force under Gates, after the detachment to Sumter, amounted (Allen's History of the Revolution, Vol. II, p. 319,) to 3,663, including officers. The British authors estimate their strength at 6,000, but as to this Col. H. Lee remarks: "Cornwallis rated Gates's forces at 6,000, in which estimation his lordship was much mistaken, as from official returns on the evening preceding the battle it appears our forces did not exceed 4,000, including the corps detached under Colonel Woolford. Yet there was great disparity of numbers in our favor, but we fell short in quality, our Continentals, horse, foot and artillery, being under two thousand, whereas the British regulars amounted to nearly sixteen hundred." Learning of Gates's approach, Cornwallis hurried up from Charleston, followed by a mounted detachment of the Sixty-third Regiment. He reached Camden the night of August 13th, the same evening Gates halted at Rugeley's. The British garrisons had been drawn in from Hanging Rock, Rugeley, Rocky Mount, and four companies from Ninety-Six. In the Camden hospital

were 800 sick, but his available force amounted in all to 2,331, including 237 officers and 40 drummers. Cornwallis resolved to force a battle. No commander was ever readier to resort to the sword for relief from difficulties. Of portly and imposing presence, vigilant,combative, resolute, his skill had been fully proven on the desperate fields of New Jersey, with Washington for antagonist. His troops had implicit confidence in him. Indeed Cornwallis was in a desperate predicament. Sumter had taken post in his rear, cutting off the main communications; swamps were all around him except on the north, and there was the American army. Says he: "Feeling little to lose by a defeat and much to gain by a victory, I resolved to take the first good opportunity to attack the rebel army." Cornwallis took every precaution to procure information as to his enemy. He sent an emissary, according to Simms, one Hughson, into the American camp, who succeeded in gaining Gates's confidence and escaping with his observations. Colonel Williams confirms this, saying: "An inhabitant of Camden came, as if by accident, into the American encampment, and was conducted to headquarters. He affected ignorance of the approach of the Americans, pretended very great friendship for his countrymen, the Marylanders, and promised the General to be out again in a few days with all the information the General wished to obtain. The information he then gave was the truth, but not all the truth, which events afterwards revealed; yet so plausible was his manner that General Gates dismissed him, with many promises if he would faithfully observe his engagements. Suspicions arose in the hearts of some of the officers about headquarters that this man's errand was easily accomplished; the credulity of the General was not arraigned, but it was conceived that it would

have been prudent to have detained the man for further acquaintance." Tarleton relates that on the afternoon of the 15th he, with a scout of cavalry, ten miles above Camden, captured three American soldiers on the road to Rugeley's, making their way from Lynches Creek. These prisoners were placed behind dragoons and hurried full speed to Cornwallis, who learned from them that they were to have joined Gates that night on his march to Camden. Cornwallis, however, in his very full account of his plans and operations, does not intimate that he had any expectation of meeting Gates upon the road that night, but rather the contrary. He says: "I determined to march at ten o'clock on the night of the 15th and to attack at daybreak, pointing my principal force against their Continentals, who, from good intelligence, I knew to be badly posted, close to Colonel Rugeley's house." At the appointed hour (10 p. m.) the British army set out on the road to Rugeley. The same day General Gates issued orders for march of his army on the same road towards Camden. The column was to be headed by Armand's legion, flanked on each side by Porterfield's and Armstrong's infantry, marching Indian file. Behind these were to follow the Maryland and Delaware regulars, the militia and baggage in the rear. The possibility of meeting the enemy on the way seems to have been contemplated, as appears from the following portion of Gen. Gates's orders:

These orders were submitted to a council of the gen- eral officers called to meet in Colonel Ruoeley's barn. Colonel Williams says that he busied himself, while the council was in session, making up a return of the number of available troops. This estimate he presented to General Gates as he emerged from the barn. The General cast his eye upon the paper, which showed just 3,052 rank and file present for duty. He expressed surprise at the small number, saying there had been no less than thirteen general officers in the council. "But," said be, "these are enough for our purpose." This purpose, Williams states, was not disclosed to him, the General only adding: "There was no dissenting voice in the council, where the orders have just been read." Some authors have stated the object of General Gates in moving his army to have been to attack and surprise Cornwallis at Camden. But there seems no doubt that the real purpose was to occupy a new and stronger position, just six miles north of Camden, on Sanders Creek, selected by the engineer of the army, Colonel Senf, and Colonel Porterfield.[5] This is confirmed by the fact that the baggage was being moved with the army.[6]

ILLUSTRATION E.

The British and Americans thus set out on the same road at the same hour, moving towards each other. The advance guard of the British column of march consisted of forty cavalry, following them in order the Twenty-third and Thirty-third Regiments, Volunteers of Ireland, Hamilton's and Bryan's North Carolina Royalist corps, the Seventy-first Regiment and Tarleton's legion bringing up the rear. They proceeded in strict silence. In crossing Sanders Creek at twelve o'clock some disorder occurred, which was soon adjusted, and the march resumed. A little past two, about one mile north of Gum Swamp, a tributary of Sanders Creek, the vans of the two armies met. Shots were exchanged at once, and flashing guns lit the night. Armand's horsemen reeled and fled, carrying confusion into the ranks behind. Porterfield's and Armstrong's light infantry, strung along the roadside, behaved well, and, according to the orders, volleyed into the British, wounded their officer, and drove them back. Musketry continued for a quarter of an hour. Colonel Porterfield was severely wounded, dying a few weeks later, probably in Camden. Prisoners were taken on either side, and from these it was ascertained the two armies were face to face. The British had marched eight miles, while in the same time the Americans had traveled five. The difference was due no doubt to the fact that the British were hastening to reach Rugeley for the daybreak attack, unencumbered, while the Americans moved leisurely, with

baggage, for a new encampment. Was the night moonless? No witness of the event has testified on this point. But astronomy has answered the question. There was a full moon on the 17th August, 1780.[7] So there was strong moonlight on the night of the 15th, but much shaded, we may suppose, by the pine forest then and there abounding. Both armies had recoiled, and as by mutual consent ceased firing and proceeded to form line. Cornwallis in his report says that he was "well apprized by several intelligent inhabitants that the ground on which both armies stood, being narrowed by swamps on the right and left, was extremely favorable to my numbers. I did not chuse to hazard the great stake for which I was going to fight to the uncertainty and confusion of an action in the dark. But having taken measures that the enemy should not avoid an engagement on that ground, I resolved to defer the attack till day." The measure taken by Cornwallis to force an action consisted, probably, in advancing his line so near the Americans that they could not risk a retreat, but must needs stand to their ground. Gates called a council of war. "What is now to be done, gentlemen?" said he to the assembled officers. There was silence for some moments, when General Stevens spoke: "Is it not too late now, gentlemen, to do anything but fight?" Silence again ensued, which implied assent. "Then," said Gates, "we must fight. Gentlemen, resume your posts." An apocryphal incident, connected with this council, has been widely accepted, upon the authority, no doubt, of the romantic Weems, in his life of Marion. He

represents that the Baron DeKalb protested against the proposal to give battle, and counseled retirement to Rugeley. Gates curtly suggested that the Baron was overprudent and overrated the danger. Stung by the innuendo DeKalb retorted: "Daylight will show us the brave," and with that indignantly returned to his command. This fable is disposed of by Colonel Williams, who tells that when he, "the deputy adjutant-general, went to call him (DeKalb) to council, he said: 'Has the general given you orders to retreat the army?'" He adds, however, "The Baron did not oppose the suggestion of General Stevens," which was to fight. As Gordon, the historian, has pertinently remarked, those officers who did not have the judgment or courage in council to oppose the proposition were not warranted, after the event, in condemning it. The imaginative Weems has also fabricated for us two other dramatic and contrasting scenes on that fateful night, the one comic, the other pathietic. At headquarters, says he, an aide familiarly asked General Gates: "General, where shall we dine tomorrow?" quite a serious question with the army at that time. "Dine, sir," replied Gates, "why at Camden, sir, begad, and Lord Cornwallis at my table. I will make pilau of him in three hours, sir." The other canvas of Artist Weems represents the veteran DeKalb in his camp conversing with his ardent young military disciples, Marion and Horry. The Baron recounts to them his life in France and his last visit to his aged parents before leaving for America; how he found his old father gathering fuel in the woods and his mother of eighty-three at the spinning wheel. He forebodes defeat. "Here are we, feeble and faint with fasting, they from high keeping strong and fierce as

butchers' bulldogs. Our army is lost as surely as ever it comes into contact with the British." Their discourse is broken by an order from Gates that Marion and Horry, with their swamp regiment of fifteen, set out at once, to go below Camden and smash all the boats on the river, thus cutting off British means of es- cape after their coming defeat. They part with the Baron in tears, who, "observing their eyes waterv2" took them by the hand, exclaiming, "NO, no, gentlemen, DO emotion for me. I will gladly meet the British tomor- row at any odds." The author adds that Horry, in his old age, declared to him: "With sorrowful hearts we left him, and with feelings which I shall never forget while memory maintains her place in this my aged brain." The veracity of which scene may be estimated by com- paring the statements of Moultrie and Williams that Marion had left the army, at his own request, two weeks before, and was probably a hundred miles away. But to return to the more certain grounds of history. The armies, formed in lines of battle through the woods throbbing with expectancy, await the morning. Shots were being constantly exchanged as parties met in the night. The British lay upon the ground, but it is not recorded that any slept. Cornwallis describes the. ground as "woody," and so it is today, except some small clearings. The situation is an elevated sandy plateau, about two miles long and one wide, sloping steadily from north to south, and rising to quite an eminence on the northwest. Streams, with boggy swamps, inclose it on the south, east, and west, and nearly so on the north. The road runs through the midst. Washington, passing over the locality on his visit South, in 1791, has recorded his opinion that neither army had any advantage of position, which should absolve Gates from having made any worse choice of ground than Cornwallis.

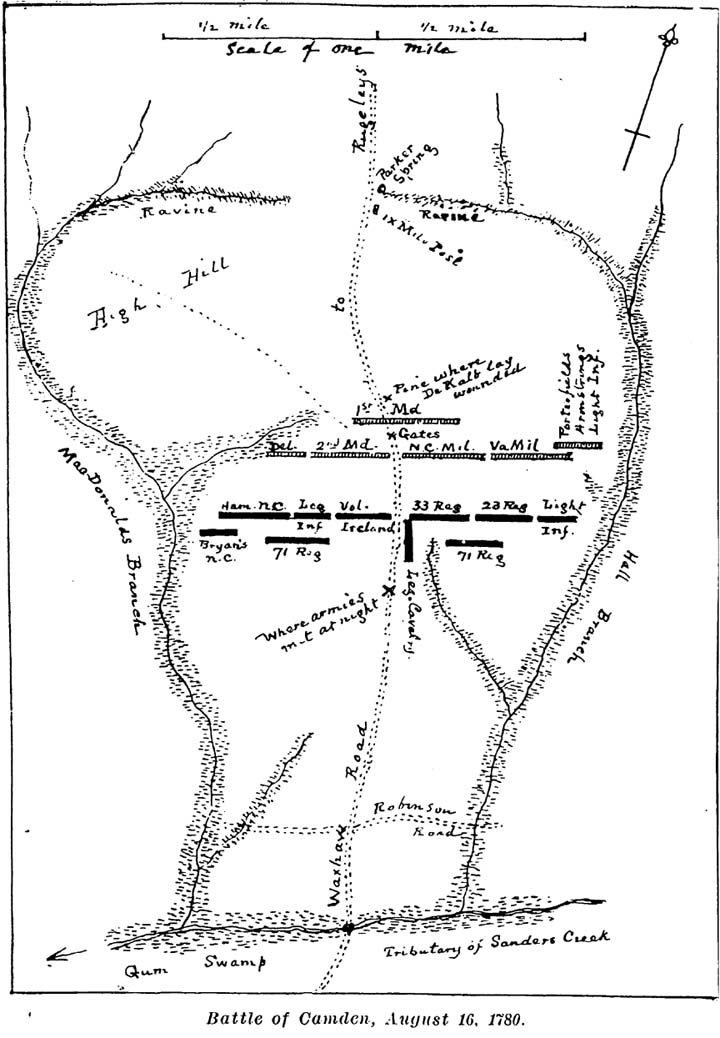

For the forces engaged, there seems to have been room enough for deployment. Colonel Williams has said: "Involved as Gates was in the necessity of fighting, the disposition which was made for the battle was, perhaps, unexceptionable, and as well adapted to the situation as if the ground had been recon- noitered and chosen by the ablest officer in the Army of the United States. It was afterwards approved by the judicious and gallant General Greene, to whom the writer had the solemn pleasure of showing the field of battle, and with whom he had the additional mortifica- tion of participating in the danger and disgrace of a repulse near the same place the very next campaign."[8] The forces on each side were aligned east and west, across the Waxhaw road, the Americans in the following order: RIGHT WING, commanded by DeKalb, composed of the Delaware Regiment, Colonel Vaughan, and Second Maryland Brigade, General Gist; CENTER, North Carolina Militia, General Caswell commanding; LEFT WING, General Stevens commanding, composed of Virginia Militia, Armstrong's and Porterfield's light infantry. RESERVE, First Maryland Brigade, General Smallwood commanding. The British were arranged thus: RIGHT, Webster commanding, the Twenty-third and Thirty-third Regiments and four companies of light infantry; LEFT, Lord Rawdon commanding, composed of Volunteers of Ireland, Tarleton's legion infantry, Hamilton's and Bryan's North Carolina Royalists; RESERVE, the Seventy-first Regiment and Tarleton's cavalry. The accompanying Diagram No. 13 will more clearly

indicate the relative positions.[9] It has been made from a careful inspection of the ground. The diagram contained in Tarleton's Memoirs, which seems to have been implicitly accepted and copied by many American historians, is very erroneous in its representation of the locality, made doubtless from memory and mere glimpses of the surroundings. Dawn was the signal for battle. The air was still and thick with haze.[10] In the early light Colonel Williams sighted some British redcoats a Short way down the road in front of the American artillery. He tells us that he ordered it to open upon them, and hurried back to General Gates, who was posted on the road between the front line and reserve, and suggested to him that the moment was favorable for an attack by the Virginians on the left. Gates approved, and Williams galloped over to convey the order. General Stevens promptly responded by giving the command to his men to advance, himself going to the front to lead them. Williams called out a band of fifty volunteers and with these went ahead of all, to draw the enemy's fire and give the militia an object lesson in courage. Cornwallis, ever vigilant, noticed the movement on the American left, and says, in his report of the battle, that he supposed it to be a change in formation taking place, affording him an opportune time to strike. So he ordered Webster to assail the American left, which was itself moving to attack. Webster with the best two British regiments went with a dash at the militia, shouting

and firing, and with bayonets set, passed right on through Williams's advance skirmishers. Stevens exhorted his men and called to them, "Come on, my brave fellows, you have bayonets as well as they." But their hearts failed. The steel of British veterans was fast upon them. At the critical moment an uncontrollable panic seized the whole Virginia brigade, and they broke in wild disorder. The North Carolinians next to them in line followed suit at once, and took to their heels, with the notable exception of a part of Dixon's regiment, who stood firm next to the Maryland regulars.[11] Colonel Williams has assured us that: "A great majority of the militia, at least two-thirds of the army, fled without firing a shot. The writer avers it of his own knowledge, having seen and observed every part of the army, from left to right, during the action." What a deplorable spectacle to meet the eyes of the American commander! He states in his report that he was amazed at the sudden confusion. It was obvious that unless some of these militia could be induced to stand, his army must be beaten. With Caswell, Stevens and his staff, he strove desperately to stem the tide of fugitives. While thus engaged his aide, Maj. Thomas Pinckney, was dangerously wounded in the thigh and captured. Shortly behind and parallel with the American lines extended two marshy ravines, a narrow pass between, and just beyond some rising ground, favorable for a rally. Here he hoped to induce them to reform, and had probably reached this point with his aides. But Tarleton's terrible dragoons had fallen upon the panic-stricken

stricken mass. Throwing away their guns unfired, they went like a torrent, bearing all before them, and scattered abroad in the woods. Tarleton's cavalry could thus close up the pass, and cut off Gates and staff, who must fly or be taken. Gates, well mounted, gets away, and with him Caswell. They cannot now return or get a word back to the troops within the ravines. A crown of thorns settles upon the brow of the victor of Saratoga. Where were Armand's horse? At this moment they might have turned the scale. Simms has answered the question thus: "Swallowed by the woods." Colonel Williams says: "What added not a little to this calamitous scene was the conduct of Armand's legion. Whether it was owing to the disgust of the Colonel at general orders, or the cowardice of his men, is not with this writer to determine, but certain it is that the legion did not take any part in the action of the 16th. They retired early in disorder, and were seen plundering the baggage of the army on their retreat." The Continentals were thus left to their fate, surrounded by swamps and British troops. No orders came to them, what must they do? Gates and Caswell had hastened back to Rugeley, the camp of the night before, thinking here enough of the flying militia might be stopped and led back to relieve the desperate pressure which must fall upon the Continentals. Webster did not long follow the militia, who had melted before him, but leaving them to Tarleton's grace, wheeled to the left upon the exposed flanks of the Marylanders and Delawares. DeKalb, who was in command of this remnant, unaware of the utter rout of the militia,[12] was hotly engaged with Rawdon in his front. The

staunch old hero was in the thick of the fray afoot, his horse having been killed under him. His men were driving the British before them and taking prisoners. But a heavy pressure comes upon them from the left. The First Maryland Brigade, the reserve, greatly disordered by the rushing militia, had somewhat recovered, and was making a stubborn resistance to Webster.[13] The battle is not yet over, and the American artillery on the road is still dealing death in the British ranks. Cornwallis recalls Tarleton's cavalry from pursuit of the militia, and to deliver the final stroke, sends them in along with his reserve. These turn the scale and the weight of numbers prevail, but not without a desperate hand-to-hand struggle. Bayonets lock and blades meet. The woods ring with the clang of steel. The cry is raised: "Save the Baron DeKalb." The bayonets have reached him. DuBuysson, his aide, embraces him, to ward off the thrusts, some of which he receives in his own body. But no mercy is shown. DeKalb lies bleeding from eleven wounds. The battle is won and lost. There is now but one way of escape, right through the boggy swamps in the rear. The Continentals, broken and routed, plunge in. Cavalry cannot follow here. Scattered through the dense thickets they dodge away, to live for future triumphs. Major Anderson, grandfather of that fine soldier of the Confederacy, Gen. Richard Anderson, "fighting Dick Anderson," was the only officer, says Williams, who rallied, as he retreated,

The British official reports give their own loss as 324 killed and wounded, including eleven missing, about fourteen per cent. of their whole force. Cornwallis, Tarleton, Stedman, all British authorities, and on the scene, give the American loss in round numbers as 800 or 900 killed and 1,000 prisoners, many of whom were wounded, which would be sixty-five per cent. of those engaged. The booty captured is given as 150 baggage wagons, twenty ammunition wagons, 670 cannon shot, eight pieces of artillery, 2,000 muskets, 80,000 balls. Of the British estimate Colonel Lee says: "Although many militia were killed during the flight, this account must be exaggerated. While the Continentals kept the field, the loss in that quarter must have been about equal. The loss the Americans sustained could never be accurately ascertained, as no returns from the militia were received. Of the North Carolina militia between three and four hundred were made prisoners and between sixty and one hundred wounded. Of the Virginia militia only three were wounded, and as they were the first to fly, not many were taken. For the number engaged the loss sustained by the regulars was considerable. It amounted to between three and four hundred men, of whom a large part were officers. The British took such as were unable to retreat. This threw between two and three hundred Continental troops into their hands." General Gates, writing from Hillsboro, August 30, 1780, says: "The militia broke so early in the day, and scattered in so many directions upon their retreat, that very few have fallen into the hands of the enemy. Seven hundred noncommissioned officers and soldiers of the Maryland division have rejoined the army." All of these statements of the American loss are vague. But in regard to the Continentals something more

authentic is furnished by Colonel Williams, deputy adjutant, in his Narrative. He gives a return made up at Hillsboro, some time after the battle. His statement is not free from ambiguity, but as we construe it, may be reduced to the following summary:

This seems to confirm the British estimate of the strength of Continentals under DeKalb and Gates at the outset of the campaign. The number of them effective and present for battle may have been less. Certain it is that enough survived this terrible disaster to take an ample revenge at Guilford, Hobkirk, and Eutaw. It was this "noble six hundred" that drove the British from the Carolinas. All honor to the invincibles of Maryland and Delaware! If one today, in leafy August, were to visit the scene of battle, he would exclaim: "Here indeed was a veritable 'war of the woods'." It has always been known locally as the "Parker Old Field," because of its ownership in former days by one Parker, although there are none of those badges in the vicinity always indicative of old fields. The present adjacent clearings are undoubtedly comparatively recent. At the date of the battle the ground was occupied by a close array of tall and stately pines, limbless to a height of forty or fifty feet. These, by the process of turpentining, have been reduced to a scanty few, so that not many of those remain that witnessed the battle. Their thinning has allowed to come up a growth of scrub oaks, which in summer obscure the view much more than did the pines. The British and Americans probably had a pretty fair view of each other at two hundred yards, while by the present growth they would have been concealed at fifty feet. Those living in that neighborhood have found amongst the leaves of the woods many an old buckle, button, bayonet, bullet, cannon ball, flintlock, and to this day diligent search will reveal some such disjccta membra of the encounter. In the Camden Journal and Southern Whig of January 24, 1835, we find this curious item: "Revolutionary Relic. The musket belonging to Levi, a French negro,

who was brought over by Lafayette and fought during the entire Revolution, was found bedded in the mud in Gum Swamp, where Levi had hidden it, being wounded at Gates's defeat. The barrel is badly eaten with rust, the bayonet eaten and broken. The powder flashed on being fired. Levi lived in Camden District for a long while after the war. The musket is now in the possession of Dr. William Blanding." A citizen of Camden says that Levi became a servant of the Whitaker family. His gun would be a prize today, could it be rediscovered. Dr. William Blanding died in Rehoboth, Mass., though many years a resident of Camden. This historic field or woodland may now be conveniently reached by a railroad line which runs within a mile of it. The nearby station has been appropriately named DeKalb.

Footnotes in original

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||