When General Clinton and Admiral Arbuthnot departed from Charleston

on the 5th day of June, to return to New York, General Cornwallis was left

in command of the British expeditionary force in South Carolina. His headquarters

were in Camden, but the troops with him, being totally destitute of military

stores, clothing, nun, salt, and other articles necessary for troops in

the operations of the field, and provisions of all kinds being deficient,

almost approaching to a famine in North Carolina," it was impossible for

the Army to penetrate into the latter Province before the harvest. Cornwallis

therefore employed himself in establishing posts from the Peedee to the

Savannah Rivers for the purpose of awing the disaffected and encouraging

the loyal inhabitants, in raising some provincial corps, and in establishing

a militia both for the defense as well as for the internal government of

South Carolina.

Major Harrison was commissioned to raise a provincial corps between

the Peedee and Wateree. Another was to be raised in the district of Ninety

Six, for which Lieutenant Colonel Cunningham was commissioned. The First

South Carolina Regiment, composed of refugees who had returned to their

native country, was recruited. In the district of Ninety Six, by far the

most populous and powerful in the Province, Lieutenant Colonel Balfour,

by his great attention and diligence and by the active assistance of Major

Ferguson, who

had been appointed inspector general of the militia of South Carolina

by Clinton, had formed seven battalions of militia consisting of about

4,000 men, which were so regulated that they could with ease furnish 1,500

men at short notice for the defense of the frontier or for any other home

service.

Many other battalions of militia were formed along the very extensive

line from Broad River to the Cheraws—

In order to protect the raising of Harrison's corps and to awe a large

tract of disaffected country between the Peedee and Black Rivers, Major

McArthur, with the Seventy-first Regiment and a troop of dragoons, was

posted at Cheraw Hill on the Peedee, where his detachment was plentifully

supplied with provisions of all kinds. Other small posts were likewise

established in the front and on the left of Camden, where the people were

known to be ill, disposed, and the main body of the army—

The information which Cornwallis had at this time of the American forces

was that General de Kalb was entering North Carolina

at the head of 2,000 Maryland and Delaware Continentals and that he

meant to make Hillsboro his headquarters; that a corps of 300 Virginia

Light infantry under Lieutenant Colonel Porterfield was somewhere in North

Carolina, some militia at Salisbury and Charlotte Town under General Rutherford

and Colonel Sumter, and a large body at Cross Creek under General Caswell.

All of these corps being at a great distance from the British, Cornwallis

did not expect that any of his posts on the frontier would be much disturbed

for two months, as he believed the Americans would find it impossible to

march any considerable body of men across the Province of North Carolina

before the harvest.

There was much business to be attended to in Charleston by Cornwallis

in regulating the civil and commercial affairs of the town and country,

in organizing militia in the lower districts, and in forwarding supplies

to the army around Camden. He planned to begin active operations about

the beginning of September, at which time he expected that South Carolina

could be left in security, while he moved with the main body of the troops

into the back part of North Carolina—

north as far as the Catawba settlement, and that many disaffected South

Carolinians from the Waxhaws and other settlements on the frontier, whom

Lord Rawdon at Camden had put on parole, were availing themselves of the

general release of the 20th of June and joining Sumter. It was also reported

that De Kalb's army was continuing its movement south, followed by 2,500

Virginia Militia. Cornwallis informed Clinton of these developments in

a letter dated July 14, stating:

The work of supplying the base at Camden with salt, rum, regimental

stores, arms, and ammunition was under way, so that a more distant advance

of the army beyond that point would be safeguarded. Due to the distance

of transportation and the excessive heat of the season, the work was one

of infinite labor, requiring considerable time. Then, too, the several

actions in which his forces had been engaged made Cornwallis more and more

doubtful as to the value of his militia. He wrote to Clinton that dependence

upon these troops for protecting and holding in South Carolina, in case

of an advance of his army into North Carolina, was precarious, as their

want of subordination and confidence in themselves would make a considerable

force always necessary for the defense of the Province until North Carolina

was completely subjugated.

In the plan of campaign for the Crown forces to the north it was contemplated

using Ferguson's corps, augmented by militia of the Ninety Six district,

which was being trained by him, as a left covering force to advance to

the borders of Tryon County, now

Rutherford and Lincoln, paying particular attention to the mountain

regions, in securing protection for the advance of the main body from Camden.

Lieutenant Colonel Cruger, who succeeded Balfour in command of Ninety Six,

was to retain his post. Colonel Innes, with the remainder of the militia

of that district, was to guard the frontier, which would require careful

attention, as there were many disaffected and many constantly in arms.

On the 9th of August two expresses reached Cornwallis from Camden, wherein

Rawdon informed him that General Gates was advancing toward Lynches Creek

with his whole army, supposed to amount to 6,000 men, exclusive of a detachment

of 1,000 men under Colonel Sumter. It was thought that the latter, following

his attack on the posts at Rocky Mount and Hanging Rock, was trying to

get around to the left of the British Army and cut off its communications

with the Congarees and Charleston. The disaffected country between the

Peedee and Black Rivers was reported as having actually revolted, and as

a result of these menaces Rawdon was contracting his post and preparing

to assemble his force at Camden. A hurried message had been sent to Lieutenant

Colonel Cruger to forward to Camden, without loss of time, the four companies

of light infantry stationed at Ninety Six.

On the evening of the 10th of August Lord Cornwallis, with a small escort,

set out from Charleston and hastened to Camden. The journey of 140 miles

was completed in three days, Cornwallis crossing the Wateree Ferry at Camden

the night of the 13th. On this same day the four companies of light infantry

arrived from Ninety Six. The British at this time knew that the American

Army had marched up Little Lynches Creek to Hanging Rock Creek, thence

to Rugeley's, where it arrived on the 13th, and that later in the day it

advanced its light Infantry across Granneys Quarter Creek, on the road

to Camden.

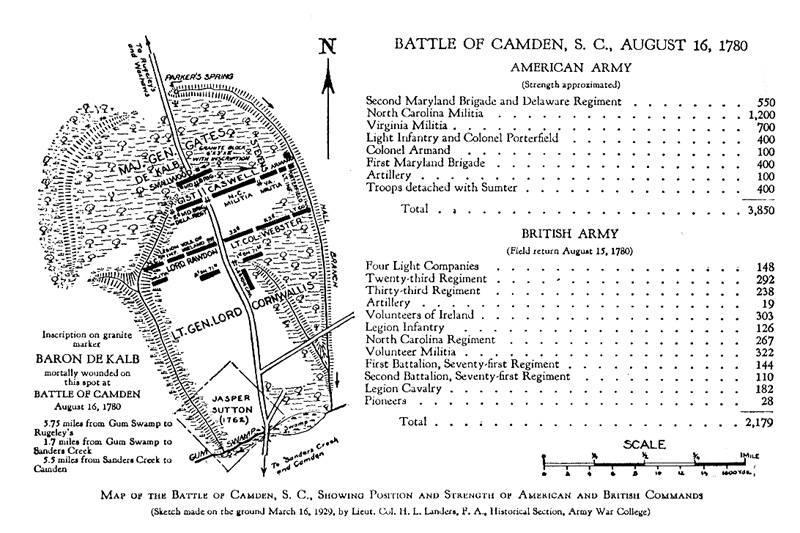

Map of the Battle of Camden, S. C., Showing Position and Strength of

American and British Commands. (Sketch made on the ground March 16,

1929, by Lieut. Col. H. L. Landers. F. A., Historical Section, Army War

College)

[40]

nothing on their front more alarming than a raiding or reconnoitering

party. Not one, in those silent columns of more than 5,000 men, knew that

the foe was approaching in full strength and with sinister purpose.

THE BATTLE OF CAMDEN, AUGUST

16,1780

Suddenly out of the quiet came a sharp challenge, an interchange of

scattered shots, and then loud huzzas of challenging troops. The van of

both armies came together at 2.30 o'clock in the morning on the Sutton

farm, which was about 8 miles from Camden, just north of the ford over

Gum Swamp. The British Legion cavalry dashed ahead to overcome by surprise

and shock whatever might block their path. Armand's cavalry stood the charge

for only a moment. The flanking columns of Infantry, under Armstrong and

Porterfield, were prompt to get into position, from which their fire took

the Legion cavalry in the flank, causing its precipitous retreat and the

wounding of its commander. Meanwhile Colonel Webster was moving the British

front division into position, and it was not long before the four companies

of light infantry and the Twenty-third and Thirty-third Regiments were

posted across the road, forming a wall behind which the Legion cavalry

could rally and the remainder of the army halt in safety and recover from

the surprise of the rencounter.

In the first clash between the two advance parties the wounded in Armand's

legion retreated and threw the whole of his corps into confusion. The corps

recoiled suddenly against the front of the column of Infantry behind, creating

disorder in the leading brigade, the First Maryland, and occasioning a

general consternation throughout the whole extent of the Army. But this

confusion in the main body was of no consequence, as the advance guard

of light Infantry bravely and effectively held the ground in front, thereby

providing time for the various organizations in rear to reestablish their

poise. Lieutenant Colonel Porterfield, in whose bravery and judicious conduct

great dependence was placed,

[41]

received a mortal wound in the first rencounter and was obliged to retire,

but his Infantry continued to hold their ground. Musketry fire was exchanged

for nearly a quarter of an hour, when the two armies, finding themselves

opposed to each other, ceased firing as though by mutual consent to determine

upon the next move.

The prisoners taken by each side during this scrimmage soon informed

their captors of the true condition of affairs. Cornwallis was assured

by both prisoners and deserters that the whole of Gates's army was marching

with the intention of attacking the British at Camden. From them Cornwallis

learned that the force confronting him was far greater than his own. From

one of the British who had been made a prisoner Colonel Williams obtained

the startling information that five or six hundred yards in front lay the

whole British Army, represented as consisting of about 3,000 regular troops,

commanded by Lord Cornwallis in person. Each side was as much surprised

at the astounding information as was the other. The situation least expected

to arise—that is, to encounter the opposing army on the march and in the

dark—had become a fearful reality, requiring the exercise of prompt and

heroic qualities of leadership on the part of each commander were he to

save his command from destruction and turn surprise into victory. Day,

light was fast approaching; by half past 4 o'clock the dawn of the coming

day would bring the armies within view of each other. But little more than

an hour was left in which to deploy the troops into battle formation.

Confiding in the discipline and courage of the King's troops, and well

apprised by several inhabitants that the ground on which both armies stood,

being narrowed by swamps on the right and left, was extremely favorable

for his numbers, Cornwallis did not choose to hazard the great stake for

which he was going to fight to the uncertainty and confusion to which an

action in the dark is so peculiarly liable. His command, composed largely

of highly trained troops, could be maneuvered into line of battle before

day broke, but he resolved to defer the attack until dawn. A byway which

[42]

led to Camden, beyond the morass on the left, gave him some uneasiness

for a short time, lest the Americans should pass his flank, but the vigilance

of a small party in that quarter soon dispelled his anxiety.

The British battle line was formed with Webster's division on the right,

the four light companies, 148 strong, being on the flank and reaching to

the swamp. Next came the Twenty-third Regiment, of 292 officers and men;

then the Thirty-third Regiment, 238 strong, with its left resting on the

road over which it had marched from Camden. On the left of this road the

division commanded by Lord Rawdon was formed. His own regiment, the Volunteers

of Ireland, with a total strength of 303, joined the left of the Thirty-third

Regiment. Then came 126 men of the Legion infantry, and beyond them were

267 of Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton's North Carolina regiment, protected

by a morass on their left flank. Some of Colonel Bryan's regiment, who

had been brought together following their defeat at Hanging Rock on the

6th, formed in rear of the North Carolinians. There was a total of 322

volunteer militia present.

In the line of battle were two 6-pounders, and two 3-pounders under

Lieutenant McLeod, posted to the left of the road and in front of the right

of the Irish Volunteers. The Seventy-first Regiment, with two 6-pounders,

was formed as a reserve, the First Battalion of 144 officers and men being

posted about 200 yards in rear of the Thirty-third Regiment, and the Second

Battalion, with a strength of 110, the same distance in rear of the Volunteers

of Ireland. The cavalry of the Legion, with a total strength of 182, was

in rear to the right of the road, and, the country being wooded, it was

drawn up close to the Seventy-first Regiment, with orders to seize any

opportunity that might offer to break the enemy's line and be ready to

protect its own in case any corps should meet with a check.

The British soon recovered from the disorder occasioned by the first

alarm, but for a long time the American Army was gripped

[43]

by fear. Order was finally restored in the corps of Infantry, and the

officers became engaged in forming line of battle, when the deputy adjutant

general communicated to General Gates the information he had received from

the prisoner. The astonishment of the commanding general upon learning

that the entire British Army was but musket shot away could not be concealed.

He ordered Colonel Williams to call a council of war with all possible

celerity. The general officers immediately assembled in rear of the line,

and the unwelcome news of the enemy was communicated to them. General Gates

then asked:

Gentlemen, what is best to be done?

All were mute for a few moments, when General Stevens exclaimed:

Is it not too late now to do anything but fight?

No other advice was offered, and Gates directed his generals to repair

to their respective commands and continue the deployment of the troops

into formation for battle. When Colonel William went to call General de

Kalb to the council, he told him what had been discovered. The latter facetiously

remarked:

Well, and has the general given you orders to retreat

the Army?

Not that De Kalb expected such an order would be given, for he had learned

to respect the determination of the man who succeeded him to the command

and knew that without a fight the Army could not withdraw, except at the

risk of being cut to pieces.

At length the Americans were ranged in line of battle in the following

order: General de Kalb's corps, composed of the two brigades of the Maryland

division and the Delaware regiment, was going into position on the right.

In the center was the North Carolina Militia, commanded by General Caswell.

The left wing was made up of the Virginia Militia under General Stevens,

the light Infantry, and Porterfield's corps. Both flanks of the line were

protected by the swamps which covered the enemy's deployment.

[44]

The swamp on the west side approached the road in the vicinity of the

American line, and it was found that the Second Brigade of about 400 men,

commanded by General Gist, and the Delaware regiment of about 150 men would

fill the ground from the road to the creek which bordered the swamp. The

Army reserve consisted of the First Maryland Brigade of approximately 400

men, under General Smallwood. The first position of the reserve was across

the road and about 200 yards in rear of the front fine.

The North Carolina troops were organized into three brigades, each consisting

of about 400 men and commanded by Brigadier Generals Gregory, Butler, and

Rutherford. One of Gregory's regiments was in charge of Colonel Dixon,

a Continental officer. This regiment was next to the Second Maryland Brigade.

The Virginia Militia numbered 700 and the fight Infantry and Porterfield's

corps about 400. The few men still left in Armand's legion were ordered

to the left to support the militia on that flank and oppose the enemy's

cavalry. Six pieces of artillery were assigned to the front line, two on

the road, two between the Second Maryland Brigade and the swamp, and two

between the North Carolina and Virginia troops. The remaining two pieces

were on the road with the reserve brigade. The total strength of the American

Army at this time was about 3,300 officers and men, as the detachment which

had been sent to join Colonel Sumter numbered somewhat more than 400.

As the night gave way to the coming day out of the darkness appeared

the dim visage of the ghostly armies. Every eye was strained to catch a

movement of the enemy; every heart beat with fear of the unknown and hope

of some advantage in troops and position. Cornwallis advanced his line

of columns preparatory to forming battle front and while doing this was

able to perceive the two lines of the Americans, now very close to him.

At the same instant his movement was detected by Captain Singleton, who

commanded two pieces of the artillery and who remarked to Colonel Williams

that he could detect the British uniform at about 200 yards in front.

[45]

The deputy adjutant general immediately ordered Captain Singleton to

open fire with his battery and then hastened to join the commanding general,

who was in rear of the reserve brigade, and informed him that the enemy

seemed to be deploying their column by the right. The suggestion was made

by this staff officer that if the enemy, while deploying from parallel

columns into line, were briskly attacked by General Stevens's brigade,

which was already in line of battle, the effect might be fortunate. The

order that this be done was given by General Gates, and Colonel Williams

hastened to deliver it to General Stevens. At the same time orders were

given to General Smallwood, commanding the reserve brigade, to advance

to the left front and support the left wing on the ground about to be vacated

by the Virginia Militia. General Gates then rode up to General Gist and

ordered the Second Brigade to advance slowly, reserving its fire until

close to the enemy, when it was to fire and charge with the bayonet.

General Stevens meanwhile advanced his brigade in compliance with the

order given him to attack, all the men apparently in fine spirits, but

it was soon discovered that the right wing of the enemy was now in line

and that it was too late to make a surprise attack upon them while they

were still deploying. Seeing this, Colonel Williams requested General Stevens

to let him have 40 or 50 volunteers, who would run ahead of the brigade

and commence the fight. They were led forward to within about 50 yards

of the British and ordered to take to trees and keep up as brisk a fire

as possible. Colonel Williams hoped, by this expedient, to draw the enemy's

fire at some distance, thereby rendering it less terrible to the militia

at the outset.

This stratagem, however, was doomed to failure, for Cornwallis, observing

the movement which had taken place in front of his right wing and supposing

that it indicated an intention on the part of the Americans to make some

alterations in their order of battle, directed Colonel Webster to begin

the attack, and the latter was now moving up with this object in view.

There was a dead calm

[46]

at the time, preventing the smoke of battle from rising, which added

to the haziness in the air. Due to the obscured atmosphere, it became difficult

to seethe effect of the very heavy fire which ensued. The British line

continued to advance in good order with the cool intrepidity of experienced

soldiers. General Stevens, observing the steady approach of the enemy,

told his men to use their bayonets, but the impetuosity with which the

British continued on, firing and huzzaing—

threw the whole body of the militia into such a panic,

that they generally threw down their loaded arms and fled, in the utmost

consternation. The unworthy example of the Virginians was almost instantly

followed by the North Carolinians; only a small part of the brigade commanded

by Brigadier General Gregory, made a short pause.

This terrible havoc in the militia troops was being wrought by the companies

of fight infantry and the Twenty-third Regiment. The advantage which they

gained they judiciously followed, not by pursuing the fugitives, but by

wheeling on the left flank of the Continentals, who were now abandoned

by all their militia except the North Carolina regiment under Colonel Dixon.

The contest at this time was supported by the two Maryland brigades, the

Delaware regiment, Dixon's regiment, and the artillery. Almost the entire

militia, constituting two-thirds of the Southern Army, had fled without

firing a shot. Colonel Williams in writing of these events said:

He who has never seen the effect of a panic upon a multitude

can have but an imperfect idea of such a thing. The best disciplined troops

have been enervated and made cowards by it. Armies have been routed by

it, even where no enemy appeared to furnish an excuse. Like electricity,

it operates instantly; like sympathy, it is irresistible where it touches.

The regular troops, who had the keen edge of sensibility and fear rubbed

of by strict discipline and hard service, saw the confusion with but little

emotion. Some irregularity was created by the militia breaking pell-mell

through the First Maryland Brigade, but order was restored in time to give

the British a severe check,

[47]

which abated the fury of their assault and obliged them to assume a

more deliberate manner of acting. The most severe part of the action occurred

on the front of the Thirty-third Regiment, which advanced on the right

of the road, and on the front of the Volunteers of Ireland, who went forward

on the left of the road. The latter regiment, together with the Legion

infantry and the militia and supported by the Second Battalion of the Seventy-first

Regiment, engaged the Second Maryland Brigade and the Delaware regiment,

which at the time were advancing to meet them. At the same time the right

division, composed of the Thirty-third and Twenty-third Regiments and the

light companies and supported by the First Battalion of the Seventy-first,

having cleared the militia from its front, was now encountering Smallwood's

brigade of Marylanders, which had moved up east of the road in line with

Gist's brigade.

The disparagement in numbers of the two armies at this phase of the

action was not so great, there being about 1,300 regular infantry of the

British opposed to about 1,000 Continentals, but there was no way of checking

the flanking movement which the British were making against the First Maryland

Brigade. There were no more reserves, and the brigade was compelled to

give ground. It fell back reluctantly and collectedly, and then a moment

later, under the rallying cry of some of its officers, it bravely returned

to the fray. It was obliged to give way a second time and was again rallied

and renewed the contest. Meanwhile the Second Brigade, fighting under the

immediate leadership of De Kalb and Gist, was more than holding its own,

inflicting heavy losses upon the Volunteers of Ireland.

There was now a distance of nearly 200 yards between the two Maryland

brigades, and owing to the thickness of the air dependence had to be placed

upon the hearing, and not upon the eyesight, to learn what was occurring

on a different part of the battle field. At this critical moment the deputy

adjutant general, anxious that communication between the brigades should

be preserved and hoping,

[48]

in the almost certain event of a retreat, that some order might be sustained,

hastened from the First to the Second Brigade and begged his own regiment,

the Sixth Maryland, not to fly. He was answered by its commander, Lieutenant

Colonel Ford, who said:

They have done all that can be expected of them; we

are outnumbered and outflanked; see the enemy charge with bayonets!

General Cornwallis now had all of his regiments concentrated against these

two gallant brigades. A tremendous fire of musketry on both sides was kept

up for some time, with equal perseverance and obstinacy, until Cornwallis

pushed forward a part of his cavalry under Major Hanger to charge the American

left flank, while Lieutenant Colonel Tarleton led forward the remainder.

The infantry, charging at the same time with fixed bayonets, put an end

to the contest. The battle was terminated in less than an hour. The British

victory was complete. All the artillery and a great number of prisoners

fell into their hands. The dead and wounded lay where they fell and the

rout of the remainder was thorough. General Gist moved from the battle

field with about 100 Continentals in a body by wading through the swamp

on the right of the American position. Other than this not even a company

retired in any order; everyone escaped as he could. The brave De Kalb had

his horse killed under him and continued to fight on foot with the Second

Brigade until he fell into the hands of the enemy mortally wounded, pierced

with eight bayonet wounds and stricken with three musket balls. This brigade

had fought with such a great measure of success, and the thickness of the

air preventing observation of other parts of the battle field, De Kalb,

when wounded and taken, could not believe that General Gates had been defeated.

As soon as the rout of the Americans became general the Legion dragoons

advanced with great rapidity toward Rugeley's. On the road General Rutherford

and many others were made prisoners. The charge and pursuit having greatly

dispersed the British, a halt was ordered on the south side of Granneys

Quarter Creek in order

[49]

to collect a sufficient body to dislodge a small party of Americans

that was employed in rallying the militia at that pass and in sending of

the baggage. The junction of Tarleton's cavalry soon caused this group

of Americans to continue the retreat. The chase again commenced and did

not terminate until the British cavalry reached Hanging Rock, 22 miles

from the battle field, by which time the Americans were dispersed and fatigue

overpowered the exertions of the British.

CONDUCT OF GENERAL GATES

DURING THE BATTLE

As soon as the firing in the night had commenced General Gates rode

to the head of the column to learn the cause and the extent of the threatened

danger. There he met some of Armand's legion retreating and was urged by

the commander to retire from the point of danger. Gates answered that it

was his duty to be wherever it was most necessary to give orders, and he

remained at the front until the firing grew slack and the troops were beginning

to form. When the conflict opened at dawn he was with the reserve brigade,

and it was there his deputy adjutant general found him and received the

order directing Colonel Stevens to attack at once. At the same time Gates

turned to one of his aides, Maj. Thomas Pinckney, of South Carolina, with

the order:

Now Sir! do you go to Baron de Kalb and desire him to

make an attack on the enemy's left to support that made by General Stevens

on the right.

When, to the great astonishment of General Gates, the left wing, composed

of Stevens's Virginians, gave way, followed immediately by almost all of

Caswell's North Carolinians, his world was shaken to its foundations. The

chance of battle, which is always a threatening factor on the battle field,

seemed about to strike him a deathblow. Were the laurels of Saratoga to

be snatched from his brow and strewn in the dust? Was his proud head to

be bowed down with humiliation, an army destroyed, and the Southern States

brought to the verge of ruin? Were the "southern willows" to be his future

[50]

decoration? These militia of North Carolina and Virginia, why should

they not be expected to fight in defense of their homeland? It is true

that the five years of war had brought much discontent with the militia

system. It was condemned by every military leader in the Revolutionary

cause, and it had not one supporter. But the cause of complaint was directed

more to the difficulty of getting the militia to stay with their organization

rather than to the question of their bravery when once cornered and forced

to face the enemy at close quarters.

Indifferent they might be to orders of their own officers, of camp restrictions,

injunctions against plundering, requirements of camp guard; ambitious their

general officers might be to retain independent commands and gain glory

through their own leadership; but who was there in all that number of high

ranking officers that fore, saw the terrifying effect upon these untried

troops when first they faced the fire of an enemy? There was no one. That

the Virginians and North Carolinians, a combined force of more than 2,000

officers and men, would be equal to the demands placed upon them was the

opinion held by all.

No deployment of the Southern Army other than the one made was possible.

The front to be covered was 1,200 yards long from swamp to swamp. The Continentals

were too few in number to cover this front; but even had it been possible

to so dispose of them, such a tactical arrangement would have been foolish.

The reserve of the Army should come from the best troops, and nothing less

than one brigade of the Continentals would serve this purpose. That left

a brigade and the Delaware regiment to constitute a wing of the battle

front. They were sufficient in number to occupy the ground from the right

of the road to the swamp, a distance some, what less than 400 yards. From

the left of the road to the swamp was a much greater distance, about 800

yards, room enough to form three brigades of North Carolina Militia in

the center, with the Virginians and other detachments in the left wing.

[51]

The American commander was not fighting from choice; in a rencounter

engagement the fighting is rarely ever from choice. It was the lesser of

two evils which General Gates chose, the greater being to retreat without

offering battle. He had planned to reach his proposed position north of

Sanders Creek as a surprise movement to Lord Rawdon in Camden. Now that

the plan could not be consummated, he would fight where he stood; he was

confident that his more than 3,000 men would give a good account of themselves.

There was no occasion to be concerned about the Continentals; they would

fight as courageously under their immediate commander, De Kalb, as under

the Army commander.

It was the militia therefore that was General Gates's chief concern.

When their line began to waver, break, and was then transformed into a

crazed mob, stampeded with fear, it was into their midst the commanding

general rode, and with indignation demanded of them that they stand and

show themselves men. He was assisted in his efforts by Generals Caswell

and Stevens and other officers. Everything in their power was done to rally

the broken troops, but to no purpose, for the British cavalry, coming around

the left flank of the Maryland division, completed the rout of the militia,

leaving the Continentals, Dixon's regiment, and the artillery to stand

alone, faced by the entire British Army.

A futile hope was entertained by General Gates that at Clermont he might

rally a sufficient number of the militia to cover the retreat of the Regulars.

Further and further to the rear was he carried in his efforts, to find

some point of lodgment for at least a handful of the fleeing troops, where

they might recover from their panic and again be brought into a semblance

of order. Tarleton's cavalry, however, was hanging so persistently on their

heels that the road was cleared of all the fleeing Americans, they seeking

safety in the adjacent woods and swamps. General Gates therefore concluded

to retire toward Charlotte Town, 65 miles from the battle ground, which

place he and General Caswell reached late that night, abandoned by all

but their aides.

[52]

During the course of the retreat, Colonel Senf, who had been on the

expedition with Colonel Sumter, returned and overtook General Gates. He

brought the agreeable news that the expedition west of the Wateree had

met with complete success. The British redoubt opposite to Camden had been

reduced, a convoy of stores from Charleston captured, and upward of 100

prisoners and 40 loaded wagons were in the hands of Sumter's party, which

had sustained very little loss. Unfortunately it was not in General Gates's

power to take advantage of this success or to attempt at the time a junction

of the remnants of the Southern Army with Sumter's corps.

The Virginians, who knew nothing of the country they were in, involuntarily

reversed the route they came and fled to Hillsboro. The North Carolina

Militia fled in different directions, most of them taking the shortest

way home. The regular troops, it has been observed, were the last to quit

the field. Major Anderson, of the Maryland line, was the only officer who

rallied, as he retreated, a few men of different companies, and whose prudence

and firmness afforded protection to those who had joined his party. Colonel

Gunby, Lieutenant Colonel Howard, Captain Kirkwood, and Captain Dobson,

with a few other officers and 50 or 60 men, formed a junction and proceeded

together.

The general order for moving off the heavy baggage to Waxhaws the preceding

evening had not been carried out. The whole, of it consequently fell into

the hands of the British, as well as all the baggage that followed the

Army, except the wagons of Generals Gates and de Kalb. Other wagons succeeded

in getting out of danger, but the cries of the women and the wounded in

the rear and the consternation of the flying troops so alarmed some of

the wagoners that they cut out their teams, and each taking a horse left

the rest for the next that should come. Others were obliged to give up

their horses to assist in carrying off the wounded, and the whole road

for many miles was strewn with signals of distress,

[53]

confusion, and dismay. What added not a little to the calamitous scene

was the conduct of some of Armand's legion in plundering the baggage of

the Army.

The morning following the arrival of Generals Gates and Caswell in Charlotte

Town the former realized the uselessness of attempting to establish the

rendezvous of the scattered army at that place. There was neither munitions

of war nor food, and the probability that the successful British Army would

rapidly pursue loomed big. Gates therefore proceeded with all possible

dispatch to Hillsboro, 140 miles from Charlotte Town, where the General

Assembly of North Carolina was about to convene. Working in conjunction

with the governor and assembly, he hoped to devise some plan for the defense

of as much of the State as it might yet be possible to save from the enemy.

Hillsboro was reached on the 19th of August. The first duty devolving

upon the defeated general was the preparation of a report of the disaster

to his army for the President of Congress. The report was dated the 20th

of August and was carried to the Governor of Virginia, thence to Congress

in Philadelphia, by the department engineer officer, Colonel Senf, and

Major McGill, an aide to the commanding general. Both of these officers

had been careful observers of what transpired within the Army, and Colonel

Senf, upon rejoining the remnant of the Southern Army the night of its

defeat, made careful inquiries as to what had occurred and from the information

gathered prepared a plan of the battle and a narrative of events. Major

McGill, in a letter written shortly after the battle, said:

We owe all misfortune to the militia, had they not run

like dastardly cowards, our army was sufficient to cope with them, drawn

up as we were upon a rising and advantageous ground.

These staff officers were sent with General Gates's report because they

were loyal to the commanding general and could "answer any questions and

clear up every doubt" that might arise in a Congress

[54]

which would become unfriendly as soon as the result of the battle became

known.

ESTABLISHMENT OF THE ARMY

IN THE VICINITY OF HILLSBORO

In the summarization submitted to Congress of events which transpired

after July 25, the date when Gates assumed command of the Army, to the

time of writing his report he said that

most assuredly the small arms are gone, for those that

the enemy did not take are carried of by the militia;

that there were no intrenching tools; and that all the artillery with the

Army, eight pieces, was lost. He stated that the distresses of the campaign

almost exceeded description, that

Famine, want of tents for the militia, and of every

comfort necessary for the troops in this unwholesome climate, has no doubt,

in a degree, contributed to our ruin.

In his despondency these difficult conditions loomed bigger in retrospect

than they did when being endured. Likewise in his statement—

It is considerable consolation to my mind that I never

made any movement of importance, or took any considerable measure, without

the consent and approbation of all the general officers,

was the desire to palliate results by a division of responsibility, which

had not occurred during the campaign. General Gates was 52 years old at

this time. His military training began in England in his early youth. As

a soldier his experience was varied. Temperamentally he was not disposed

to conduct war in accordance with the majority view of a council of officers.

That the failure of his army would be charged solely to him he was ready

to believe and expect. Writing to General Caswell on the 22d of August

he said:

While I continue in office will exert my utmost to serve

the public interest, but as unfortunate generals are most commonly recalled,

I expect that will be my case, and some other Continental general of rank

sent in my place to command. When he arrives I shall give him every advice

and information in my power; in

[55]

the meantime, I doubt not, Sir, that the candor and

friendship that has subsisted between us, will continue, and that you are

infinitely superior to the ungenerous custom of the many who, without benefiting

themselves, constantly hunt down the unfortunate.

A TRIBUTE TO GENERAL DE KALB

In recalling the heroes of Camden the American mind will dwell upon

Gist and Smallwood and the other brave leaders of the Continental troops,

but to none of those who survived the conflict will such honors be accorded

as are due General de Kalb. His memory is immortalized by the manner of

his death. He gained glory that General Gates would gladly have acquired

at the same cost. He survived his 11 wounds until the third day, dying

on the 19th of August, attended by his devoted aide-de-camp and friend,

Le Chevalier du Buysson. General de Kalb's dying command to his aide was

to deliver a message to Generals Smallwood and Gist, presenting his affectionate

compliments to all the officers and men of his division and expressing

the greatest satisfaction in the testimony given by the British Army of

the bravery of his troops. He was proud of the firm opposition to superior

force made by his division when abandoned by the rest of the Army. The

gallant behavior of the Delaware regiment and the companies of Artillery

attached to the brigades afforded him infinite pleasure—

and the exemplary conduct of the whole division gave

him an endearing sense of the merit of the troops he had the honor to command.

General Washington, in writing to Du Buysson in eulogy of De Kalb, said:

The manner in which he died fully justified the opinion

which I ever entertained of him, and will endear his memory to the country.

The death of Baron de Kalb was deeply lamented in Maryland, and his memory

is honored in that State. As a testimonial of their respect and gratitude

the legislature passed an act granting the right of citizenship to his

sons.

[56]

RESOLUTIONS PASSED

BY CONGRESS

Congress on the 14th day of October, 1780, passed the following resolutions:

Resolved, That a monument be erected to the memory

of the late Major General the Baron de Kalb, in the city of Annapolis,

in the State of Maryland, with the following inscription:

SACRED TO THE MEMORY OF THE BARON DE KALB

KNIGHT OF THE ROYAL ORDER OF

MILITARY MERIT,

BRIGADIER OF THE ARMY OF FRANCE

AND MAJOR GENERAL IN THE SERVICE

OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

HAVING SERVED WITH HONOR AND REPUTATION

FOR THREE YEARS,

HE GAVE A LAST & GLORIOUS PROOF OF HIS ATTACHMENT

TO THE LIBERTIES OF MANKIND

AND THE CAUSE OF AMERICA

IN THE ACTION NEAR CAMDEN IN THE STATE OF SO. CAROLINA

ON THE 16TH OF AUGUST 1780

WHERE LEADING ON THE TROOPS OF

THE DELAWARE & MARYLAND LINES AGAINST

SUPERIOR NUMBERS

AND ANIMATING THEM BY HIS EXAMPLE

TO DEEDS OF VALOUR

HE WAS PIERCED WITH MANY WOUNDS

AND ON THE 19 FOLLOWING EXPIRED

IN THE 48 YEAR OF HIS AGE,

THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

IN GRATITUDE TO HIS ZEAL, SERVICES AND MERIT

HAVE ERECTED THIS MONUMENT.

Resolved, That the thanks of Congress be given

to Generals Smallwood and Gist, and to the officers and soldiers of the

Maryland and Delaware lines; the different corps of artillery; Colonel

Porterfield's and Major Armstrong's corps of light infantry, and Colonel

Armand's cavalry; for their bravery and good conduct, displayed in the

action of the 16th of August last, near Camden, in the State of South Carolina.

Resolved, That the thanks of Congress be given

to such of the Militia officers and soldiers who distinguished themselves

by their valour on that occasion.

For more than a century no action was taken to erect the monument in De

Kalb's memory. It was not until February 19, 1883, that Congress appropriated

a sum of money for this purpose.

[57]