|

CONTENTS

PART II

PART III

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The principal battle grounds of the first four years of the War for Independence, waged by the thirteen Colonies against the mother country, were located in the Northern States, following which period, in the latter part of 1779, predominance of military activities was transferred to the South, where it remained until hostilities between the United States and England were, in effect, terminated at Yorktown on the 19th day of October, 1781, by the surrender of Lord Cornwallis's army to General Washington. The military history of the Revolutionary War during these latter years is to be found almost entirely in the campaigns, battles, and partisan warfare which occurred in Virginia, the two Carolinas, and Georgia. The Province of Georgia was overrun by the British in 1779, and Savannah and Augusta fell into their hands. Early in September the French Comte d'Estaing, with 20 ships of the line and 11 frigates, having on board 6,000 soldiers, suddenly appeared of the southern coast. He had successfully battled the British admiral commanding in the West Indies and was now come to assist in driving the British troops from Georgia. A plan was soon arranged between D'Estaing and Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln, commanding the Southern Department, to besiege Savannah, but after protracted operations in the months of September and October the attempt met with ignominious failure. The French then sailed for the West Indies, and the American troops, under General Lincoln, returned to Charleston, S. C. The departure of the French from the coast, after being repulsed at Savannah, left Sir Henry Clinton, who commanded the British Army in America from Nova Scotia to West Florida, at liberty to attempt the long-projected reduction of the Southern Provinces. At his headquarters in New York he planned with Vice Admiral Mariot Arbuthnot, commanding the British Fleet in American waters, to lead an amphibious expedition against Charleston, with the intent of occupying both the Carolinas, thereby giving support to the Tories in the South and popularizing the Crown cause. The importance of this move was considerably augmented by the fact that Virginia tobacco, exported from the Chesapeake, contributed largely to the financial resources of the Americans, and the appearance of a hostile fleet in southern waters would curtail this traffic very materially. The expedition sailed from New York on the 26th day of December, 1779. The land forces consisted of about 8,500 men, well supplied with artillery, military stores, and provisions. The command of the King's troops left at New York devolved upon the Hessian general, Baron von Knyphausen. During the winter of 1779-80 the Continental Army was quartered in the jerseys and upon the Hudson River. Washington's headquarters was at Morristown, about 25 miles west of the town of New York. The seat of government was at Philadelphia, sufficiently near to Washington's headquarters for his friends in Congress to lean heavily upon him and his enemies to harass him with their nefarious machinations to effect his downfall. There was little that could be done, either by Washington or Congress, to sustain the South in the struggle about to be precipitated upon its territory, for the all-important concern of each was for the maintenance and preservation of the Army which protected the Northern States. Events transpiring south of the Chesapeake merely presented collateral issues, to which only limited thought and assistance could be given by the Central Government; the salvation of the Southern States was left largely to themselves for accomplishment. England was complete mistress of the Atlantic seaboard, her fleet holding the harbors of Halifax, Penobscot, New York, and Savannah. The army left by Clinton in the North was more than a match for the 10,000 American troops under arms during these winter months. Until the draft of militia joined in the late spring of 1780, and its numbers were known, no plan of campaign for the following summer could be decided upon. Washington wrote to the President of Congress on the 3d day of April: The Commander in Chief at once determined to aid the South with such Continental troops as might be spared, despite the fact that every man under arms was needed in the North, where progress of the enemy and save the Carolinas." There was every reason to believe that should the British succeed in capturing Charleston the Southern States would become the principal theater of war.

On the 2d of April Washington informed the President of Congress that the Maryland line and the Delaware regiment, which acted with the Maryland line, a total force of about 2,000 men, would be put under marching orders immediately if Congress acquiesced in his views as to the propriety of taking such action. The expedition was to be led by Major General Baron de Kalb, who commanded the Maryland division. Anticipating that Congress would assent to his plans, Washington, on the 4th of April, ordered De Kalb to proceed immediately to Philadelphia and there learn from Congress whether or not the troops were to move. If so, he was directed to make all necessary arrangements with the Board of War, the Quartermaster General, and the Commissary to transport, equip, and ration his command. General de Kalb arrived in Philadelphia on the 8th day of April and learned that Congress had adopted Washington's recommendations concerning the expedition and was making the necessary preparations for it. The troops, to the number of 1,400, broke camp at Morristown on the 16th of April and after several days' march reached Philadelphia, where the force was divided, the artillery, ammunition, and baggage proceeding south by land and the Infantry marching to the head of Elk River, where it embarked on the 3d of May. The Board of War fixed upon Richmond as the place of rendezvous for the whole. De Kalb was detained in Philadelphia by the Board of War until the 13th of May to complete his affairs, and on that day he set out to join his command. Two days were spent at Annapolis waiting for funds, for the Maryland troops, to be paid by the State of Maryland, and on the 22d of May Richmond was reached. There it was found that Governor Jefferson had removed the rendezvous of the troops to Petersburg, 27 miles farther south. The troops now under De Kalb's command were the Maryland and Delaware Continentals and a Virginia regiment of 12 pieces of artillery, which had previously departed from Petersburg on its march south. He was promised further reenforcements of militia from Virginia and North Carolina� Orders were at once dispatched to the first brigade and the regiment of Artillery, which on the 6th of June crossed into North Carolina, to halt where they were until De Kalb could join them with the second brigade, at which time he would consider what steps to take, determine whether or not a junction could be effected with Governor Rutledge, of South Carolina, and the troops under his command, and weigh the prospects of obtaining additional militia from Virginia and North Carolina. Fearful that the strength of the British troops in South Carolina was far superior to his own numbers, De Kalb determined to hold his command on the defensive until reenforced, and on the 6th of June, before leaving Petersburg, wrote the Board of War to that effect, adding that he would expect� Although Charleston had capitulated and its garrison made prisoners, the British had not yet gained any considerable foothold elsewhere in the Province, and it was presumed that the presence of a body of regular troops would do much to sustain the fortitude of the militia. The State of Virginia now awoke to its own interests sufficiently to make increased efforts to facilitate the movement of De Kalb's force, but on the whole the assistance rendered was so meager that his advance was very slow. It was not until the 20th of June that he reached Goshen, 15 miles inside the border of North Carolina. At Hillsboro the troops were retted a few days; then they continued on to the settlement which is now Greensboro and on the 6th of July reached Wilcox's iron works on Deep River, where they were again brought to a halt for want of provisions. The difficulties attendant upon the march, lack of food, limited transportation, long stretches of barren and unsettled country, the pestilential voraciousness of insects, violence of thunderstorms, the indifference of the inhabitants to the Revolutionary cause, all these things were strange to De Kalb, who was accustomed to warfare only in Europe, and he feared that he might be compelled to retreat, for want of provisions, without striking a blow. In writing to a friend regarding the difference between warfare in Europe and in the southern part of the United States De Kalb said that Europeans did not know what warfare was, that they "know not what it is to contend against obstacles." The State of North Carolina had made no provision for the troops of the Union; it was solely occupied with its own militia, which could be maintained only with difficulty, as the Tory sympathizers outnumbered those who were loyal to the Revolutionary cause. De Kalb's applications and protestations to the governor produced but little effect. It was necessary to send small detachments throughout the surrounding country to collect provisions from the inhabitants, who at this season of the year had but little to spare. In this dilemma the troops remained several days; but the resources failing in the vicinity of the camp, it became necessary to draw supplies from a greater distance or march to where there was greater plenty. The former was impracticable, as the means of transportation were not in De Kalb's power, so the alternative of marching to where there was a greater plenty was decided upon. A small magazine of supplies was gathered together at Coxe's mill, on Deep River, where the troops arrived on the 19th day of July and encamped near Buffalo Ford. In the new camp it was soon found that shortage of supplies still continued. There was scarcely sufficient grain even for the immediate subsistence of the troops, and the only meat ration that could be procured was lean beef, driven daily out of the woods and cane, brakes, where the cattle had wintered. Inaction, bad fare, and the difficulty of preserving discipline when there was no apprehension of danger were circumvented only by the activity of the officers and the enthusiasm of the entire command to hasten the time when they would encounter the foe. The situation in which this expeditionary force found itself was brought to the attention of Congress by De Kalb, and he repeatedly remonstrated to the Governor of the State of North Carolina because of his delay in furnishing aid. Promises were made that a plentiful supply of provisions would be provided and that the Continentals would be joined by a considerable force of militia, under Maj. Gen. Richard Caswell, of North Carolina. It was in vain that De Kalb called repeatedly upon Caswell to join his command, and it was equally fruitless to expect much longer to find subsistence for his soldiers in a country where marauding parties of militia swept all before them. He was therefore undecided whether to march his force to join the militia, with the hope of finding that General Caswell's complaint of a want of provisions for himself was fictitious or to move up the country and gain the fertile banks of the Yadkin. Before any decision was made, however, the approach of Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates to take command of the expeditionary force was announced by the arrival of his aide-de-camp, Major Armstrong. When the campaign of 1779 terminated in the North and the troops went into winter quarters, General Gates left his command and returned to his home at Travellers Rest, in Berkeley County, Va., where he passed the winter and spring months and awaited recall to duty in the 1780 campaign. This recall came on the 4th day of June in a letter from General Washington, written when the summer campaign was fast approaching. Just three days before writing this letter Washington received the first definite information of the capitulation of Charleston. This information, although disheartening, was in no wise a surprise, as such a termination of the siege operations being conducted by the British against that city had been anticipated. General Lincoln being taken prisoner at the surrender, it became necessary for Congress to designate a new Commanding general for the Southern Department. It was not deemed advisable to intrust the command to Baron de Kalb, and on the 13th of June Congress appointed General Gates to the position. It was Gates who commanded the army to which General Burgoyne surrendered at Saratoga in 1777, and this success made him one of the most popular of the American leaders. Later the glory which attached to his name was dimmed, in the minds of some, by his machinations against Washington, but despite the exposure of his participation in the Conway cabal Gates had more friends in Congress during the year 1780 than did the Commander in Chief His appointment to the Southern Department was made without consulting Washington. His acceptance of the honor and responsibility was contained in a modest declaration, addressed to the President of Congress, to do his utmost to serve his country under conditions in the field which, he knew, would try to the utmost his patience and ability. He asked for no indulgence for errors of the heart; for those of the head alone did he expect compassion. General Gates set out from Travellers Rest on the 26th day of June to join his command, tarrying several days in Fredericksburg, Va., to answer dispatches from Congress and write numerous letters. One of these letters was to General Lincoln, dated July 4, wherein Gates expressed a soldierly sympathy for that officer, requested advice on any matter which might be useful to him, and stated his wish to restore Lincoln to his former command. The difficulties which Gates knew confronted him were tersely expressed in the statement that he was succeeding Lincoln� After reporting conditions as he found them to the President of Congress and the Board of War, in letters written on the 20th of July, and sending orders to Brig. Gen. Edward Stevens, of the Virginia Militia, and Colonel Buford to join with their commands without unnecessary delay, Gates cleared up a voluminous correspondence while at Hillsboro and departed from thence on the 23d, taking a direct route to Coxe's mill, where the Army lay in camp awaiting the new commander. His arrival on the night of the 24th was a great relief to De Kalb, who was finding the campaign attended with difficulties beyond the power of a commander of foreign birth and training to overcome. The following day the troops were paraded and a salute fired to General Gates from the little park of artillery. Besides the Maryland division and the Delaware regiment, there were present a small legionary corps under the command of Colonel Armand, Marquis de la Rouerie, consisting of about 60 Cavalry and as many Infantry, and a detachment of three companies of Artillery, which had joined in Virginia. The Virginia Militia and such Continental corps of Cavalry and Infantry from that State as Congress had allotted to serve in the Southern Department were on the march and were expected to join shortly. A meeting of all general officers who were to serve under Gates was called for the 27th of July for the purpose of determining upon a plan of campaign. A letter was sent to General Caswell to attend this meeting and to bring with him Brigadier Generals Rutherford and Harrington. The first order issued by General Gates upon assuming command was to pay General de Kalb the compliment of confirming his standing orders. Then, much to the surprise of everyone, he ordered the troops to hold themselves in readiness to march at an hour's warning. To those who knew the precarious wants of the troops this order was a matter of great astonishment. The march of the Army from Petersburg to Coxe's mill had stretched the nervous energy of De Kalb and his staff to the breaking point; further advance, in their minds, should be attended with delay and circumspection. It needed the appearance of a commander not already exhausted by his efforts in bringing the Army to this point to lead them onward. Some satisfaction was derived from the paragraph of the order which read: On the 26th of July a comprehensive order of march was published to the troops, and early the following morning, without waiting for Generals Caswell, Rutherford, and Harrington to join at Coxe's mill for conference, the "Grand Army", as General Gates designated his command, resumed its march, crossing Buffalo Ford and following the most direct route leading toward the enemy's advanced post at Lynches Creek, on the road to Camden. Two brass field pieces were abandoned for want of horses. De Kalb had previously left behind nine pieces of artillery, keeping ten, which he considered sufficient for the small army. With the further reduction of two pieces there were left eight with the Army. Col. Otho H. Williams, of the Maryland line, who on the 9th of July had been appointed adjutant general of the Southern Army by De Kalb, presuming upon the friendship of General Gates, ventured to expostulate with him because of the seeming precipitate and inconsiderate step he was taking in marching so soon and in the direction adopted. He represented that the country to the south, through which the general proposed to march, was barren, abounding in sandy plains, intersected by swamps, sparsely inhabited, and capable of furnishing but little provisions and forage. A more desirable route, in Williams's opinion, lay to the westward, through the higher ground of the Yadkin, thence to the town of Salisbury, located in the midst of a fertile valley, where many of the inhabitants were zealous in the cause of freedom. Williams and other officers had contemplated this route with pleasure, not only as it promised a more plentiful supply of provisions, but because the sick, the women and children, and the wounded might have an asylum provided for them at Salisbury or Charlotte Town, where they could remain in security in case of disaster to the Army. The militia of the counties of Mecklenburg and Rowan, in which these villages were located, were staunch friends. Among other considerations suggested was the advantage of turning the left of the enemy's outposts, even though the route were circuitous, and thus approach the main post at Camden by marching down the east bank of the Wateree, with the friendly settlement of Charlotte Town directly to the rear. General Gates told Colonel William he would confer with his general officers on these matters when the troops halted at noon. Whether or not such a conference occurred is not known; but if it did, it occasioned no change in the celerity and directness with which Gates moved toward his objective. That night the Army camped at Spink's, 12 miles west of Deep River. The following day, the 28th of July, Cotton's was the halting place, 15 miles from Spink's, and on the 29th Kimborough's was reached. At this time General Stevens, with the Virginia Militia, was two days' march in rear. From Kimborough's Gates sent letters to Generals Caswell and Rutherford, asking for their opinion regarding the intentions of the British commanders and urging close and immediate cooperation in aggressive action against the enemy. The three days' march from Coxe's mill to Kimborough's had developed numerous matters of discipline highly unsatisfactory to the commanding general. The loads of the overburdened wagons were increased by many of the foot troops and even the sentinels throwing their guns and equipment into them; wagons halted for frivolous reasons; the Artillery stretched along the road, unduly elongating the column; kind-hearted teamsters added to the burdens of their jaded teams by permitting women camp followers to ride, "sometimes two in one wagon." Measures were taken to correct these evils, and after a rest of two days the march was resumed on the 1st day of August. Masks Ferry on the Peedee was reached that evening. There Gates was again delayed, this time by high water in the river making the crossing a hazardous undertaking. Much of the time was occupied in writing letters to the Governors of Virginia and North Carolina and to the commanders of State troops who were supposed to be marching to join him. Gates wrote Governor Jefferson: Through information conveyed by a deserter and from his own intelligence service Gates was advised that the British had evacuated the Cheraws, and all the distant outposts covering Camden. It was believed that Cornwallis had gone to Savannah and had weakened his main army at Camden, where Lord Rawdon commanded temporarily. Gates, in his regret that the enemy was not standing to give battle, felt that want of provisions had The impatience of General Gates to push ahead determined him not to wait at Masks Ferry for General Stevens to come up with the Virginia Militia, which on the 3d was still halted at Buffalo Ford on Deep River, 50 miles in rear, unable to move for want of provisions. General Caswell continued his evasive, independent role, despite the many demands made, first by De Kalb and then by Gates, that he unite his troops with the main Army. It was now hoped by Gates that a junction would be effected at Anderson's, toward which the march from Masks Ferry was to be directed. He wrote to Caswell on the 3d of August: Green corn was cooked with lean, stringy beef from the swamps and woods, the result being a repast somewhat palatable but attended with painful effects. Green peaches were substituted for bread, with equally distressing consequences. It occurred to some of the officers that the hair powder which they carried would thicken the soup of corn and beef, and it was actually used for this purpose. Rum, which Gates declared as necessary to the health of a soldier as good food, was lacking and molasses used as a substitute. The intestinal troubles from which the troops suffered as a result of this diet produced a very enervating condition and one not conducive to bold, aggressive, and sustained fighting when time for action came. Due to the heavy rains, passage of the Peedee by the Artillery, stores and baggage was not accomplished until the 3d of August, and at daybreak the following morning the Southern Army resumed its march. The Army was joined south of the Peedee by Lieutenant Colonel Porterfield, who had retired with a small detachment of Virginians following the disaster at Charleston and had found means of subsisting his men in the Carolinas until this time. Eighteen miles were covered this day and camp made at May's mill. Another day's march of 17 miles would bring the Army to Anderson's, where Gates had ordered Generals Caswell and Rutherford to join with their commands. Shortly after midnight Gates received a letter from Caswell to the effect that he meditated an attack upon a fortified post of the British at Lynches Creek, about 14 miles from where he was then camped. A reply was returned to Caswell at once, informing him that orders would be sent to Colonel Porterfield's command of Virginians, which was 10 miles in advance of the Army, to join Caswell immediately and that Gates would march at 4 a. m. on the 5th with the First Maryland Brigade and join him with the utmost expedition. The march order of the Army for the 5th of August had been issued prior to this exchange of letters. In it the hope was expressed that the� The attack on the British post at Lynches Creek, contemplated by General Caswell, was not made, as Caswell himself later apprehended an attack on his own camp from these same troops and requested General Gates to reenforce him with all possible dispatch. determined General Gates to reach General Caswell's camp in person that same day. Colonel Williams accompanied him on this visit and in his narrative says: On the 5th of August the Army marched 17 miles to Anderson's on Deep Creek. The following day Colonel William was made deputy adjutant general of the department, replacing Major Armstrong, who had been appointed to this position on the 3d of August and was now relieved on account of illness. The long wished for junction of General Caswell's troops occurred on the 7th at Deep Creek Cross Roads. After the junction, which happened about noon, the Army marched a few miles toward the enemy's post at Lynches Creek and camped on Little Black Creek. Baron de Kalb was placed in command of the right wing, composed of regular troops, and General Caswell of the left wing, made up of militia. morning. That night Colonel William, feeling much anxiety as to whether or not the militia guards were alert, accompanied the officer of the day on an inspection of all the lines. Early the next morning before the break of dawn the "General" was sounded, followed by the "March," as soon as the troops were paraded. The Army moved of by the left, which put the North Carolina Militia in the lead. Contact with the enemy's outpost at Lynches Creek, 14 miles away, was expected to be made by General Gates about 9 o'clock. The commands of Armand and Porterfield had marched through the night and reached Lynches Creek before daybreak, but when dawn came no appearance of the enemy was revealed to them. It was learned that the British outpost had been withdrawn during the night, and a deserter from the command gave intelligence to the Americans that the detachment fell back to an eminence 4 miles beyond Little Lynches Creek and took up a position which it was proposed to hold until the cool of the evening. Not to be denied the spoil of the chase, Gates, from his camp at Lynches Creek, ordered Porterfield with the Virginia troops, the light Infantry of Caswell's division, and a detachment of Cavalry to hasten in pursuit of the fleeing enemy, hang upon his rear with pertinacity, and bring him to a stand. An additional body of 600 men was to march early the same evening to support Porterfield's detachment; but there was delay in effecting an organization of this force, and it did not get away from camp until the following morning, the 9th. The commander, Colonel Hall, was ordered to proceed 6 miles on the road leading to Camden by Little Lynches Creek, where he was to select an advantageous position and remain until receipt of further orders from Gates unless he found it necessary, meanwhile, to advance in support of Porterfield. The parole for the 9th of August was "Saratoga", meant as a harbinger of good luck. With the near approach to the enemy it was again necessary for General Gates to endeavor to rid his column of excess baggage, both animate and inanimate. The Army was still encumbered with an enormous train of heavy luggage, a multitude of women, and not a few children. An escort was therefore formed under Major Dean of the Maryland line to convoy a wagon train to Charlotte Town. All the sick and the heavy baggage were sent to the rear and as many of the women as could be driven from the line. Many of the latter, however, preferred to share every toil and danger with the soldiers to accepting the security and provisions promised at some rendezvous in the rear. The Army left its camp at Lynches Creek at 4 o'clock in the morning of the 10th of August. The right wing, made up of the Continentals, was in front, General Smallwood's brigade of Marylanders leading. Upon approaching Little Lynches Creek it was learned that the British were holding a commanding position on Robertson's place south of the stream, that the way leading to it was over a causeway on the north side to a wooden bridge, which stood on very steep banks, and that the creek lay in a deep, muddy channel, bounded on the north by an extensive swamp and passable nowhere within miles but in the face of the enemy's work. To attempt to force a passage by the bridge was unwarrantedly hazardous, and it became necessary, for once, that General Gates depart from the shortest route to his objective and march by a devious path. It was well that no attempt was made to force this crossing, as the position was held by Lord Rawdon with the Twenty-third, Thirty-third, and Seventy-first Regiments, the Volunteers of Ireland, Hamilton's corps, about 40 dragoons of the Legion, and four pieces of cannon. The infantry of the Legion and part of Colonel Browne's regiment were posted at Rugeley's. The American Army bivouacked that night at Lynches Heights. Rum was issued, and the troops were held in readiness to assemble at their alarm posts upon every alarm. Early the next morning, the 11th, the Army marched by the right flank up the north bank of Little Lynches Creek, cover for the rear of the column in this flank movement being provided by General Butler's North Carolina Militia and the Cavalry and Infantry under Colonel Armand and Lieutenant Colonel Porterfield. On the 12th the march was continued to Marshall's plantation on Little Lynches Creek. On the 13th of August Clermont was reached, the home of Lieutenant Colonel Rugeley, 13 miles north of Camden. Clermont was beautifully situated on gently rolling ground, which sloped to the southeast 700 yards to Granneys Quarter Creek and to the southwest 400 yards to Big Flat Rock Creek. Seventy-five yards southwest of the house was a well-constructed log barn, which was used at various times as sleeping quarters, council chamber, and fort. A mill on Granneys Quarter Creek, about 400 yards northeast of the highway, ground grain for the community. Lieutenant Colonel Rugeley was an ardent loyalist and Clermont was used habitually as a rendezvous for Tory militia. This flank march of the Americans from Little Lynches Creek induced the British detachment south of the creek to retire to Camden, as did the garrison which had occupied Clermont. The Southern Army had its numbers greatly increased on the 14th of August, when General Stevens reported with 700 militia from Virginia. At this time Colonel Sumter was at Waxhaws in

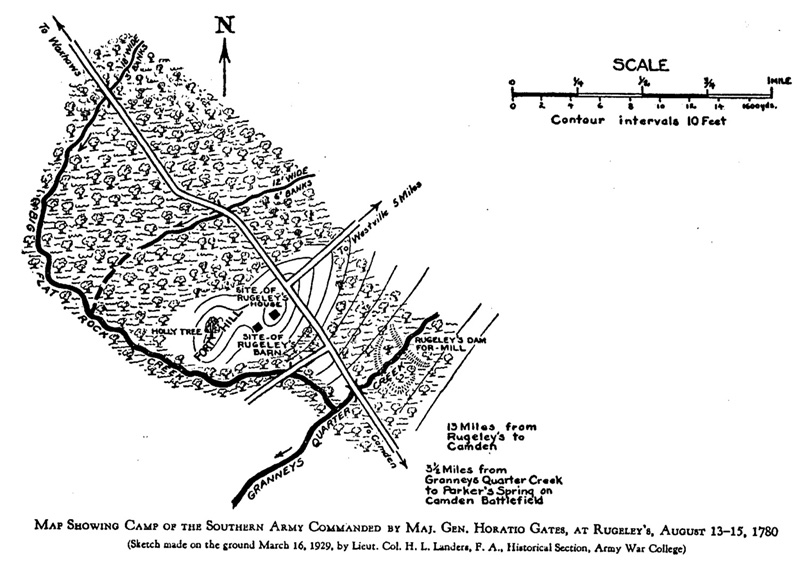

MAP SHOWING CAMP OF THE SOUTHERN ARMY COMMANDED BY MAJ. GEN. HORATIO GATES, AT RUGELEY'S, AUGUST 13-15, 1780 the Catawba settlement, at the head of a considerable body of South Carolina Militia. He had fallen back to this locality, following a sharp engagement on the 6th of August at Hanging Rock, to collect more men and recuperate. Upon the arrival of General Gates at Rugeley's he sent word to Sumter to march from the Waxhaws, and as soon as reenforcements, which Gates would provide, joined him to proceed down the Wateree opposite to Camden and intercept any stores coming to the enemy and capture reenforcements marching from Ninety Six to Camden. The intelligence received at the Southern Army headquarters at Clermont on the 13th and 14th made the commanding general very hopeful that within a brief period he could strike a blow that would cripple the enemy. An aggressive move by Sumter down the west bank of the Wateree, made in cooperation with the march of the Army directly on Camden, would do much to insure success. As General Gates considered his numbers more than twice those of the British, late at night on the 14th he sent the department engineer, Colonel Senf, with 300 North Carolina Militia, 100 of the Maryland line under Lieutenant Colonel Woolford, and two 3-pounders to reenforce Sumter. The junction was effected the morning of the 15th, west of Rugeley's, at which time Sumter was moving down the right bank of the Wateree in pursuance of his mission. Under cover of Armand's legion and Porterfield's corps, staff officers inspected the terrain in the direction of Camden for the purpose of selecting commanding ground to which General Gates might march his army and offer battle to Cornwallis. Being uncertain as to the extent of the works covering Camden, Gates did not propose attacking the British in position with an army composed largely of untried militia. There was no advantage, however, in remaining longer at Clermont, now that Sumter was moving down the Wateree, and much was to be gained by reducing the distance to Camden and from a well-selected defensive position await developments. If Sumter were able to hold the fords of the Wateree

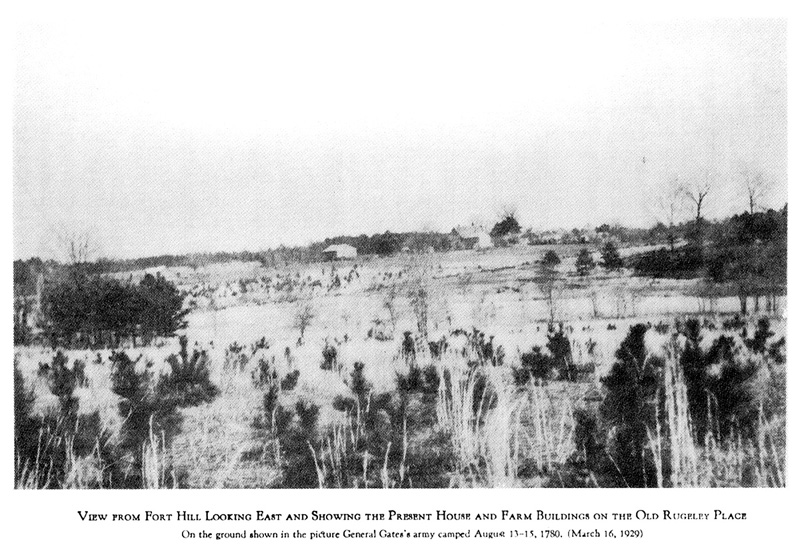

View from Fort Hill Looking East and Showing the Present House and Farm Buildings on the Old Rugeley Place. On the ground shown in the picture General Gates's army camped August 13-15.1780. (March 16,1929) across which passed the roads from Charleston and Ninety Six, the British in Camden would soon feel the pinch of hunger, and Cornwallis, would be compelled to attack Gates in position in order to relieve the pressure around him. An advantageous position was found by Colonel Senf and Lieutenant Colonel Porterfield on the north bank of Sanders Creek, about 7½ miles from Rugeley's and 5½ miles from Camden. The entire country from Clermont to Camden was wooded. From Granneys Quarter Creek to Gum Swamp, a distance of 5¼ miles, the road follows a low ridge. At frequent intervals on both sides of the road the ridge breaks into ravines, some shallow and others abrupt. The ravines head at varying distances from the road and have the common characteristic of spreading out into impassable swamps, all of which feed into Gum Swamp. This latter obstacle was passable only where the road forded it. After crossing Gum Swamp the road again follows a slight ridge, and at a distance of 3,000 yards Sanders Creek is reached. The north bank of this stream slopes upward to a hill about 60 feet high, and at a distance of about 300 yards from the stream was the site selected for the American Army to occupy. The report of the reconnoitering officers to General Gates showed that Sanders Creek was deep and passable only at the ford where the road from Camden to Clermont crossed, that there was a thick swamp on the right and thick low ground on the left; but this latter flank was not so well secured as was the right flank, and it was proposed to strengthen it with a redoubt and abatis. Orders were given the morning of the 15th for the immediate issue of 1 pound of flour and 1 gill of molasses to every officer and soldier in camp. A return of the sick, unable to march, was called for. General Rutherford was designated officer of the day for the 16th, when it was expected that the Army would be securely located on Sanders Creek. General Gates then drafted his "After

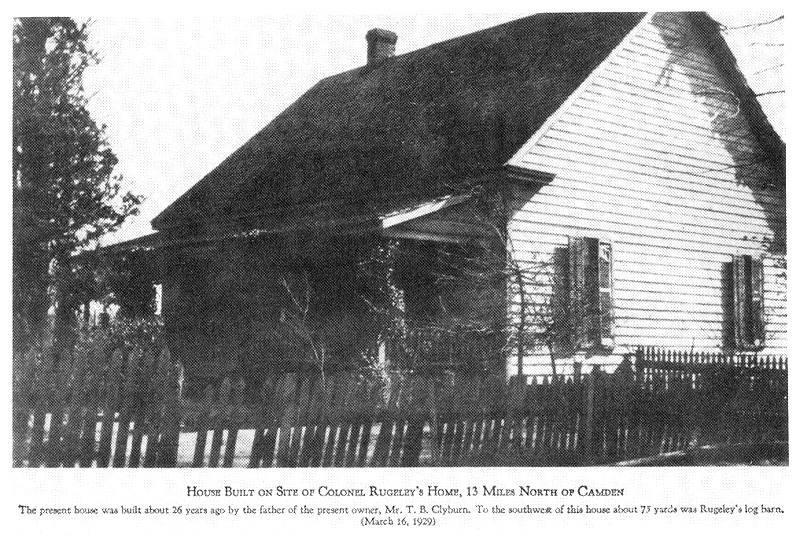

House Built on Site of Colonel Rugeley's Home, 13 Miles North of Camden. The present house was built about 26 years ago by the father of the present owner, Mr. T. B. Clyburn. To the southwest of this house about 75 yards was Rugeley's log barn. (March 16,1929) General Orders", which prescribed in detail how the troops were to march to the new camp. This order was shown to the deputy adjutant general by Gates, together with a rough estimate of the forces under his command prepared by himself, which gave a total in the neighborhood of 7,000. From his own observation Colonel Williams suspected that this calculation of the commanding general was exaggerated. Being instructed at the time to call all the general officers to assemble at Rugeley's barn, where General Gates proposed issuing his orders to them, Colonel Williams supplemented this call by directing all commanding officers of corps to bring with them a field return of their command. It was Williams's intention to check up on the actual strength in camp. The meeting in Rugeley's barn, at which General Gates communicated his plans to the general officers, occurred in the afternoon. It was not a council of war, merely an assembly of commanding officers to hear read the orders which the commanding general had prepared for their guidance and execution. The orders prescribed that the sick, extra artillery stores, heavy baggage, and such quartermaster stores as were not immediately wanted were to march that evening to Waxhaws. By this movement the line of communications of the Army was transferred from the route over which it had marched to a line running north through Charlotte Town. All tents were to be struck at tattoo and the troops ready to march that night precisely at 10 o'clock. The Cavalry of Armand's legion was to take the advance, supported on each flank by a column of foot troops marching in Indian file 200 yards from the road. The right flanking column consisted of Lieutenant Colonel Porterfield's Light Infantry, augmented by a detachment of 68 officers and men, experienced in woodcraft, selected from the Virginia division. Major Armstrong's light Infantry, increased by experienced woodsmen from the North Carolina division, formed the left flanking column. In case the enemy's cavalry were encountered on the march, mandatory orders were given the three commanders of the covering forces to brush aside all resistance. Upon discovering the enemy on the road Armand's Cavalry was to stand the first shock of the encounter, while the light Infantry on each flank instantly moved up and delivered a galling fire upon the enemy's horse. Under cover of this fire Armand was expected to rout the enemy's cavalry and drive it in disorder to the rear, "be their numbers what they may." His orders he was to consider "as positive." In rear of the covering force came the advance guard of foot, composed of the advance pickets, then the First Maryland Brigade with its artillery in front, the Second Maryland Brigade with its' artillery in front, the division of North Carolina Militia, and the division of Virginia Militia. The baggage of each brigade was in rear of the brigade. Lieutenant Colonel Edmonds, with the remaining guns of the park, marched with the Virginia troops. The train of heavy baggage followed the combatant troops and had assigned for its flank protection detachments of volunteer Cavalry, and as a rear guard a detachment of 68 supernumerary artillery officers and men. All troops were ordered to observe the most profound silence upon the march�

HOLLY TREE ON FORT HILL AT RUGELEY'S PLACE A few yards from the tree is an old well, and on the crest of the hill a brick foundation. This double tree is 32 inches across the base. It is more than 100 years old. (March 16, 1929)

duty. Gates was much surprised at the small showing, but said to Williams, "These are enough for our purpose." What that purpose was Williams did not know, but he supposed that it was to march and attack the enemy. Allowing for a due proportion of officers, noncommissioned officers, and others, the total strength fit for duty was about 3,700. The camp was soon astir with feverish activity. The two days' rest at Clermont, the accession of Stevens's Virginians, and the movement of Sumter down the west bank of the Wateree, all these things made the Southern Army keen to close in on the foe. There was some grumbling and unfavorable comment because of the orders, but that was to be expected in so diversified a command, which had not yet acquired the solidarity that comes from success on the battle field. Colonel Armand misinterpreted or misstated the tenor of the orders for his Cavalry and took exception to its being placed in the front line of battle in the dark. As a matter of fact the commanding general's orders for the conduct of the advance Cavalry were sound. He was not sending them into the "front line of battle in the dark", but was calling upon them to perform their legitimate duty of reconnaissance and delaying action. It will be seen when the march of the British column is discussed that Cavalry was at its head, ready to perform the same kind of duty that was expected of Armand's legion, which was: This implied criticism loses its value, as it was prompted by the outcome of the ensuing battle and not by an anterior evaluation of events and conditions. General Gates did not expect to meet any considerable body of the enemy on this march. He hoped to reach his goal on the north bank of Sanders Creek before daylight; nevertheless he wisely included in the order an injunction to the troops to be prepared to march in parallel columns, thereby facilitating deployment into line of battle, should the necessity arise. Return to CMH Online

|