Advanced Wargames

In the 1970s I was becoming increasingly drawn to the kriegsspiel format, whereby each player is fed only limited information by an impartial umpire - thereby avoiding the complete overview of the battlefield which is intrinsic to conventional games (both boardgames and miniatures), at the same time as it eliminates 'gamesmanship'. Since only the umpire knows the rules (assuming there are any in the first place), the players are unable to cheat by playing to their letter rather than their spirit. The best website available for this at present is Rich Madder's -

http://home.freeuk.net/henridecat

|

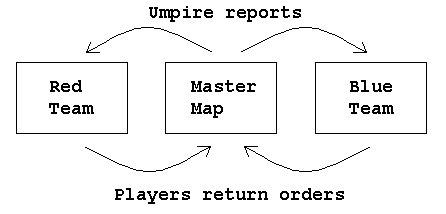

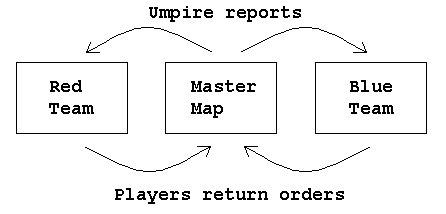

One of the main problems with this type of game is that the umpire has to keep dashing from one closed room to another, making sure that the Red team has had a chance to respond to anything it would know about, before the Blue team moves on to the turn after that, and that the Blue team is kept up to date on the effects of Red's latest decisions, and so on. Equally the master map must always be kept up to date - which sometimes means the umpire has to be in three places at the same time...

|

Beyond kriegsspiels, my varied experiences of wargaming at Sandhurst opened my eyes to still more different game formats - offering many innovative alternatives to the stultifying conventional type of 'equal points', competitive and low-history-content games which seemed to dominate club wargaming at that time. I therefore founded 'Wargame Developments' in 1980, in an attempt to pursue these alternatives further, and great progress was in fact made during the exciting first few years of hectic debates, activities and conferences. The 'Wargame Developments' website is: http://www.brazen.demon.co.uk/wd.html

Unfortunately, however, by 1983 I had come to the conclusion that the model troops themselves were the biggest obstacle to true reform, and they often came to have far more than their fair say in how games should be played. Apart from anything else, 'progress' in the toy soldier branch of the hobby often seemed to be a matter of re-inventing various wheels that had already been presented in the pages of 'Wargamer's Newsletter' during the 1960s. But because most members of 'Wargame Developments' remained wedded to 'laying lead' (a Freudian phrase indeed!), I was forced to accept that as an organisation it had completed only half its intended revolution.

Wargaming in the Media

A major turning point in my perceptions of all this had come when I wrote and ran a large-scale kriegsspiel for 'The Daily Telegraph Magazine' (No.497, May 17 1974) based on the projected 1940 German invasion of Britain, including a computerised 'Battle of Britain' phase (the computer filled a whole large room...). A number of senior officers from both sides of the 1940 firing line took part, and some were inevitably a trifle, er, 'surprised' to find that we first allowed the Germans to cross the Channel, and then actually defeated them on land! Nevertheless, the results of the game were turned into a Futura novel - 'Sealion' (ISBN 0 8600 7077 8) - written by Richard Cox.

Above: the back of my head as I direct 'Operation Sealion'. The admirals, generals and air marshals seem interested!

I know of no other novel written before Cox's 'Sealion' (itself well over a decade before the Clancy phenomenon) which drew its plot directly from a wargame (doubtless I will soon be given a list?), and in general I believe the media has largely failed to make the most of wargames. A lot more could be done, especially on radio and TV, although I have at least been involved in a few promising attempts to televise games. The first was the 1970s Tyne Tees 'Battleground' series with Edward Woodward and Peter Gilder, where six games were played with each on a single table with toy soldiers, 'open' for both players to see the whole picture.

By contrast my 'Operation Starcross' for Southern Television in 1979 was a map kriegsspiel of a possible future war between NATO and the Warsaw Pact - a subject that I also explored in a number of very large teaching games at Sandhurst. These big games led on in the 1980s to a whole series of equally large recreational games for hobby wargamers, which came to be called 'Megagames' (a name first used by Andy Callan, not me - honest!). Unfortunately neither 'Wargame Developments' nor my Sandhurst club could sustain them, so they passed to Jim Wallman's Chestnut Lodge club in South London. His 'Megagame Makers' may be found on the internet at:-

http://www.pastpers.co.uk/megagame/index.htm

The latest and most highly developed attempt to put wargames on TV was Channel 4's series 'Game of War', which was broadcast in August 1997. The series consisted of three kriegsspiels - on Naseby 1645, Waterloo 1815 and Balaklava 1854 - using playing committees of real generals, military historians and defence journalists &c. The umpiring was done by me and Arthur Harman, while the presenters were the broadcaster Angela Rippon and the editor of 'Miniature Wargames', Iain Dickie.

|

In 'Game of War' each of the two commanding generals was assisted by a team of staff officers, as they would be in real life. This concept opens yet another avenue for 'advanced' wargaming, which is to roleplay the tense debates which usually take place in a military HQ before key decisions are made. As a format it has been called a 'committee game', and it is (uniquely?) described in my 'How to Play Historical War Council Games' (Paddy Griffith Associates, Nuneaton 1991: no ISBN). In a committee game a number of players each take roles as members of a council of war or strategic planning group. Many variants are possible, with committee members being either on the same side of the argument, or violently opposed to each other (including the possibility of enemy spies sitting in on proceedings). A whole game might be devoted to one committee reaching a single decision, or there might be several committees interacting with each other, linked by umpires, each making a whole series of decisions. Conventional wargames might also be played out to see where each decision leads, so a new committee may have to be convened to react to the results...and so on.

|

The example games used in the book are the classic 'Chinese Committee 1927' where eight members of the Chinese Communist Party choose one out of eight possible party lines for the revolution (only one of them being the Maoist line that was in reality successful): 'Sidi Ferruch!', the French high command plans successive stages of the colonisation of Algeria, with a new session (and potentially a new Governor General) every year from 1830 onwards; and a 'Pentagon Committee 1991', where different US defence agencies discuss the merits of a new secret weapon, 'The Gopher'.