< Previous Page * Next Page >

Political leaders of the south, the professional classes, and most of the clergy, as they fought the weight of northern opinion, now no longer apologized for the institution of slavery but became its ardent champions. It was held to shower benefits upon the Negro, and southern publicists insisted that the relations of capital and labor were more humane under the slavery system than under the wage system of the north. Prior to 1830, the old patriarchal system of plantation government, with its easygoing methods of management and personal supervision of the slaves by their master, was still characteristic. After 1830, however, a decided change began to be apparent. With the introduction of large-scale methods of cotton production in the lower south, the master often ceased to have close personal supervision over his slaves and employed professional overseers whose reputations depended upon their ability to exact from slaves a maximum amount of work.

While many planters continued to treat their Negroes with indulgence, there were instances of heartless cruelty, and the system inevitably involved the frequent breaking of family ties. The most trenchant criticism of slavery, however, was not the inhumanity of overseers, but the violation of the basic right of every man to be free and the potentialities for brutality and repression inherent in any system of human bondage. Furthermore, according to F. L. Olmsted, a keen contemporary northern student of southern conditions, slavery "withholds all encouragement from the laborer to improve his faculties and his skill, destroys his self-respect, misdirects and debases his ambition, and withholds- all the natural motives which lead men to endeavor to increase their capacity of usefulness to their country and the world."

With the passage of years, cotton culture and its labor system came to represent a vast investment of capital. From a crop of negligible importance, cotton production leaped in 1800 to about 35,000,000 pounds, rose to 160,000,000 pounds in 1820 and, by 1840, reached a total of more than 670,000,000 pounds. By 1850, seven-eighths of the world's supply of cotton was grown in the American south. Slavery increased concomitantly. The major purpose of southerners in national politics came to be the protection and enlargement of the interests represented by the cotton-slavery system. Thus one of their main objectives was to extend the cotton-growing area beyond its existing confines. Such expansion was a necessity because the wasteful system of cultivating a single crop, cotton, rapidly exhausted theland, and new fertile areas were needed. Further, in the interest of political power, the south needed new territory out of which additional slave states might be created to offset the admission of new free states. Antislavery northerners quickly became aware of this purpose in national affairs and began to conceive of it as a malevolent conspiracy for proslavery aggrandizement.

Antislavery agitation in the north became militant in the 1830's. An earlier antislavery movement, an offshoot of the American Revolution, won its last victory in 1808 when Congress abolished the African slave trade. After that, opposition was largely limited to the Quakers, who kept up a mild and ineffectual protest, all the while the cotton gin was creating an increased demand for slaves. In the 1820's came the beginning of a new phase of agitation, which owed much to the dynamic democratic idealism of the times and to the fierce new interest in social justice for all classes.

The abolition movement in America in the more extreme phases was combative and uncompromising, defying all the constitutional and legal guarantees protecting the slavery system and insisting upon its immediate end. The extremist movement found an inspired leader in William Lloyd Garrison, a young man of Massachusetts, who combined the fanatical heroism of a martyr with the crusading ability of a successful demagogue. On January 1, 1831, the first number of his newspaper, The Liberator, appeared bearing the announcement:

"I shall strenuously contend for the immediate enfranchisement of our slave population. . . . On this subject I do not wish to think, or speak, or write, with moderation. . . . I am in earnest - I will not equivocate - I will not excuse - I will not retreat a single inch - and I will be heard."Garrison's sensational methods awakened many northerners to the evil character of an institution which they had long since come to regard as established and unchangeable. His policy was to hold up the most repulsive and exceptional incidents of Negro slavery to the public gaze and to castigate the slaveholders and all who defended them as torturers and traffickers in human life. He would recognize no rights of the masters, acknowledge no compromise, tolerate no delay. Less violently inclined northerners, however, were unwilling to subscribe to his law-defying tactics. They held that reform should be accomplished by legal and peaceful means.

One phase of the antislavery movement involved helping, under cover of night, to spirit away escaping slaves to safe refuges in the north or over the border into Canada. Known as the "Underground Railroad,", an elaborate network of secret routes for the fugitives was firmly established in the thirties in all parts of the north. The most successful operations were in the old Northwest territory. In Ohio alone, it is estimated that no fewer than 40,000 fugitive slaves were assisted to freedom during the years from 1830 to 1860. The number of local antislavery societies increased at such a rate that in 1840 there were about 2,000 of them with a membership of perhaps 200,000.

Despite the single objective of the active abolitionists to make slavery a question of conscience with every man and woman, the people of the north as a whole held aloof from participation in the antislavery movement. Busy with their own concerns, they thought of slavery as a problem for the southerners to solve through state action. The unbridled agitation of the antislavery zealots seemed to them to threaten the integrity of the Union, a matter more important to them than the destruction of slavery. However, in 1845, the acquisition of Texas and, soon after, the territorial gains in the southwest resulting from the Mexican War converted the moral question of slavery into a burning political issue. Up to this time, it had seemed likely that slavery would be limited to areas where it already existed. It had been given limits by the Missouri Compromise in 1820 and had had no opportunity to overstep them. Now with new territories supposedly suitable for a slave economy annexed to the Union, renewed expansion of the "peculiar institution" became a real likelihood.

Many northerners believed that, if kept within close bounds, the institution would ultimately decay and die. For justification of their opposition to adding new slave states, they pointed to the statements of Washington and Jefferson and to the Ordinance of 1787 which forbade the extension of slavery into the Northwest, as binding precedents. As Texas already had slavery, she naturally entered the Union as a slave state. But California, New Mexico, and Utah did not have slavery. When the United States prepared to take over those areas in 1846, conflicting suggestions about what to do with them were made by four main groups. The extreme southerners urged that all the lands acquired from Mexico be thrown open to slave-holders. Strong antislavery northerners demanded that all the new regions be closed to slavery. One group of moderate men suggested that the Missouri Compromise line be extended to the Pacific with free states north of it and slave states to the south. Another moderate group proposed that the question be left to "popular sovereignty" that is, the government should permit settlers to flock into the new country with or without slaves as they pleased and, when the time came to organize the region into states, the people themselves should determine the question. More and more, the weight of southern opinion leaned toward the view that slavery had a right to exist in all the territories. More and more, the opinion of the north inclined to the view that it had a right in none. In 1848, 'nearly 300,000 men voted for the candidates of a Free Soil Party which declared that the best policy was "to limit, localize, and discourage slavery."

|

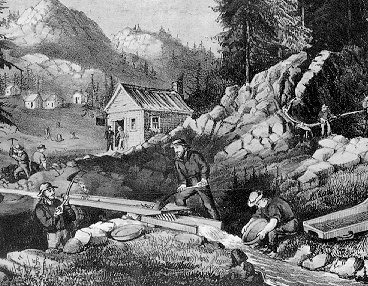

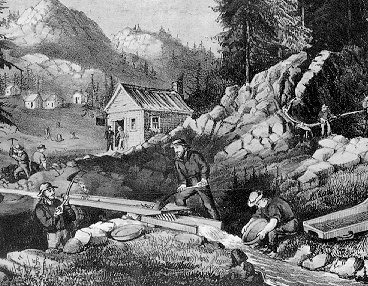

| The California "gold rush". In 1849, a year after the discovery of gold in the Sacramento Valley, more than 80,000 goldseekers arrived to transform a quiet ranching community into a region of bustling activity. |

For three short years, the compromise seemed to settle nearly all differences. Yet, beneath the surface, the tension remained and grew. The new Fugitive Slave Law deeply offended many northerners. They refused to have any part in catching slaves; instead, they helped fugitives to escape. The "Underground Railroad" became more efficient and unabashed in helping numbers to safety.

< Previous Page * Next Page >