< Previous Page * Next Page >

Lincoln had early sensed the coming struggle between the executive and the legislature over the policy of reconstruction. But solving the problems fell to the lot of his successor, Andrew Johnson. Long experienced in public life, he had intellectual courage and inflexible purpose, but unfortunately, the situation before him called also for tact and patience, and these qualities were utterly foreign to his makeup.

|

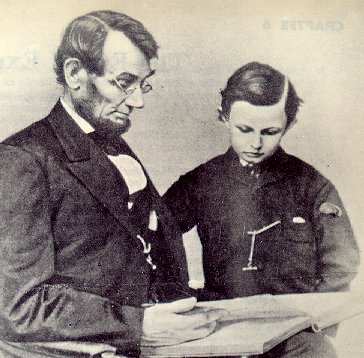

| The warmth and humanity of Abraham Lincoln's personality, together with his rare ability of statesmanship, have been the subject of innumerable literary works - stories, plays, biographies. In the picture (above) he is shown wiht his son, Tad. |

Throughout the summer of 1865, without consulting Congress, for that body was not in session, Johnson proceeded to carry out, except for minor differences, Lincoln's plan of reconstruction. By presidential proclamation, he appointed a governor for each of the various southern states and freely restored political rights to large numbers of Confederates through the use of his pardoning power. Conventions were held in the southern states which repealed the ordinances of secession,repudiated the war debt, and drafted new constitutions. In time, the people of each state elected a governor and a state legislature, and when the legislature of a state approved the Thirteenth Amendment, Johnson recognized the re-establishment of the civil government and considered the state back in the Union. With few exceptions this process had been completed when Congress convened in December 1865. But the southern states were not yet fully restored to their rightful places within the Union, because Congress had not yet seated their Senators and Representatives who now came to Washington, once again to take part in the enactment of laws for the United States.

Both Lincoln and Johnson recognized that Congress would have the right to deny the southern Representatives a seat in Congress under that clause of the Constitution which says that "Each house shall be the judge of the ... qualifications of its own members." Under the leadership of Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, those who sought to punish the south refused to seat the southern delegates, and in the next few months they proceeded to work out a plan of Congressional reconstruction quite different from that which Lincoln had started and Johnson completed.

A mixture of motives caused Congress to reject the Johnson plan. During a war, the power and prestige of the President is, because of the very nature of things, likely to be enhanced, but after the war Congress seeks to reassert its authority. In 1865, there was a feeling that the time had come for Congress to curb the executive's exercise of powers which, under the necessities of war, it had tolerated. Furthermore, there was some feeling in the north that the south should be punished with severity. This feeling was encouraged by the radicals in Congress. They first took advantage of the fact that many southerners who now sought office had ten months before taken an active part in the war to destroy the Union. The vice-president of the Confederacy, for instance, presented himself now as Senator from Georgia. From the southern point of view, the election of their leaders to office was natural, but it was a particularly bitter pill for northerners to swallow.

In addition, it was claimed that the Negro needed protection. As time passed, the idea gained currency that the Negro be given the right to vote and hold office and that he be given complete social and political equality with white citizens. Others, including Lincoln, favored a more gradual enfranchisement with full citizenship rights being first extended to educated Negroes and those who had served in the Union army. But the southern legislatures, created under the Johnson plan, enacted a variety of laws designed to regulate the privileges and rights of the freedmen. To the southerner, confronted with the problem of 3,500,000 Negroes but recently emancipated from slavery, it seemed necessary that the states regulate their activities closely, and they enacted "black codes" of a restrictive nature. To many in the north, this seemed as if the gains of the war were being undone, and northern radicals seized upon the most obnoxious features of these codes to prove that the south was bent on re-establishing slavery.

< Previous Page * Next Page >