FRtR > Outlines > American Economy (1991) > A historical perspective on the American Economy > Colonial Economy

An Outline of the American Economy (1991)

3/12 A historical perspective on the American Economy

3/14 Colonial Economy

*** Index * < Previous * Next > ***

Whatever early colonial prosperity there was resulted from

trapping and trading in furs. In addition, the fishing industry

was a primary source of wealth in Massachusetts. But throughout

the colonies, people relied primarily on small farms and

self-sufficiency. Households produced their own candles and

soaps, preserved food, brewed beer and, in most cases, processed

their own yarn to make cloth. In the few small cities and among

the larger plantations of North and South Carolina and Virginia,

some necessities and virtually all luxuries were imported -- in

return for tobacco, rice and indigo exports, which produced large

profits in England's London, Bristol and Liverpool markets. In

these areas, trade and credit were essential to economic life.

Supportive industries developed as the colonies grew. A variety

of specialized operations, such as sawmills and gristmills, began

to appear. Shipyards were opened to build fishing fleets and, in

time, to build the basic merchant marine; oak, which had become

relatively rare in England, was easily available in New England.

Iron manufacturing also gradually began to develop in the

colonial era.

Supportive industries developed as the colonies grew. A variety

of specialized operations, such as sawmills and gristmills, began

to appear. Shipyards were opened to build fishing fleets and, in

time, to build the basic merchant marine; oak, which had become

relatively rare in England, was easily available in New England.

Iron manufacturing also gradually began to develop in the

colonial era.

By the 18th century, regional patterns of development had become

clear and reasonably stable: The New England colonies produced

large-scale ship builders and ship operators; plantations in

Maryland, Virginia and the Carolinas grew staple crops of

tobacco, rice and indigo; and the middle colonies of New York,

Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware were shippers of general

crops and furs. In all three regions standards of living were

very high -- higher for workers than in England itself. But

because the colonies were slow to show profits, many English

capital investors withdrew, leaving the field open to

entrepreneurs among the colonists.

As a result, by 1770 the North American colonies were

economically and politically ready to become part of the emerging

self-government movement, which had dominated English politics

since the time of James I (1603-25). Disputes developed over

taxation of colonies and other matters.  Yet few Americans thought

that the mounting quarrel with the English government would lead

to independence for the colonies. Rather, they hoped for a

modification of English taxes and regulations that would satisfy

their demand for a greater measure of self-government. Like the

English political turmoil of the 17th and 18th centuries, the

American Revolution was political and economic in motivation, led

by the emerging middle class with its rallying cry of

"unalienable rights to life, liberty and property" -- a phrase

openly borrowed from English philosopher John Locke's Second

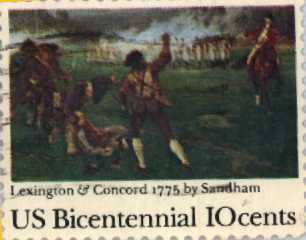

Treatise on Civil Government (1690). But in April 1775 an

event occurred that would lead to a total political separation.

British soldiers, intending to capture a colonial arms depot at

Concord, Massachusetts, and forestall a colonial rebellion,

clashed with colonial militiamen and someone-no one knows

who-fired a shot, beginning the American War of Independence. The

war lasted until the signing of a peace treaty in 1783 that

declared the independence of the new nation, the United States.

Yet few Americans thought

that the mounting quarrel with the English government would lead

to independence for the colonies. Rather, they hoped for a

modification of English taxes and regulations that would satisfy

their demand for a greater measure of self-government. Like the

English political turmoil of the 17th and 18th centuries, the

American Revolution was political and economic in motivation, led

by the emerging middle class with its rallying cry of

"unalienable rights to life, liberty and property" -- a phrase

openly borrowed from English philosopher John Locke's Second

Treatise on Civil Government (1690). But in April 1775 an

event occurred that would lead to a total political separation.

British soldiers, intending to capture a colonial arms depot at

Concord, Massachusetts, and forestall a colonial rebellion,

clashed with colonial militiamen and someone-no one knows

who-fired a shot, beginning the American War of Independence. The

war lasted until the signing of a peace treaty in 1783 that

declared the independence of the new nation, the United States.

*** Index * < Previous * Next > ***

Supportive industries developed as the colonies grew. A variety

of specialized operations, such as sawmills and gristmills, began

to appear. Shipyards were opened to build fishing fleets and, in

time, to build the basic merchant marine; oak, which had become

relatively rare in England, was easily available in New England.

Iron manufacturing also gradually began to develop in the

colonial era.

Supportive industries developed as the colonies grew. A variety

of specialized operations, such as sawmills and gristmills, began

to appear. Shipyards were opened to build fishing fleets and, in

time, to build the basic merchant marine; oak, which had become

relatively rare in England, was easily available in New England.

Iron manufacturing also gradually began to develop in the

colonial era.

Yet few Americans thought

that the mounting quarrel with the English government would lead

to independence for the colonies. Rather, they hoped for a

modification of English taxes and regulations that would satisfy

their demand for a greater measure of self-government. Like the

English political turmoil of the 17th and 18th centuries, the

American Revolution was political and economic in motivation, led

by the emerging middle class with its rallying cry of

"unalienable rights to life, liberty and property" -- a phrase

openly borrowed from English philosopher

Yet few Americans thought

that the mounting quarrel with the English government would lead

to independence for the colonies. Rather, they hoped for a

modification of English taxes and regulations that would satisfy

their demand for a greater measure of self-government. Like the

English political turmoil of the 17th and 18th centuries, the

American Revolution was political and economic in motivation, led

by the emerging middle class with its rallying cry of

"unalienable rights to life, liberty and property" -- a phrase

openly borrowed from English philosopher