The Sugar Act and the Stamp Act had failed to gain revenue from the American colonists, but men were still in Parliament devising plans of how the Americans would be convinced to pay. William Pitthad a plan to get Parliament to forget about the colonists' refusal to pay taxes to them for the time being by introducing a new idea involving "The East India Company [whom] . . . British military forces had supported. . . . [William Pitt, the earl of] Chatham . . . proposed that the company should pay an annual rental to the government and that the dividend policy of the East India Company should be regulated by the government to prevent speculation in the company's stocks. [Furthermore], revenues from the East India Company could have made up the national deficit and averted the taxation issues with the American colonies"[23] . This bill, however, was refused. The bold refusal of the American colonists was a slap in the face for Parliament, and it was far from forgotten. A plan to repay the debt was not enough. Parliament wanted a plan that would convince the colonists to pay their taxes. This particular test became a challenge, and in 1767 Charles Townshend, a man seeking popularity, took that challenge.

Townshend was a man that had been around in Parliament to vote for the Stamp Act when it was popular, and then voted to repeal it when doing so was the popular thing [24]. No man in Parliament had been able to come up with a plan that would convince the colonists to pay their taxes since Parliament started paying attention to them after the Seven Years War. Townshend decided that the best way to increase his popularity was to get the American colonists to obey Parliament and pay their taxes peacefully. In order to do this, he took into consideration the speech that Franklin had delivered several years earlier. Franklin had said that internal taxes were too cumbersome, and that the people in the colonies would always oppose an internal tax. An external tax, however, would be treated with a bit more respect in the colonies -- or at least, that is what Parliament was led to believe. Townshend wanted to be the man who extracted the desired taxes from the colonies, so he devised a plan which would involve an external tax. "Charles Townshend . . . gambled an empire for the sake of popularity. . . ." He decided that in "expressing their aversion to the internal taxes such as the Stamp Act, [the Americans] had admitted the validity of Britain's right to impose duties"[25] .

The Townshend Acts first involved the old Navigation Laws. Burke did not oppose these laws, as he had the others introduced by Townshend, because he did not feel that the colonies would protest against the Navigation Laws. They were "traditional commercial regulations. They were the corner stone of British colonial policy; they protected and promoted imperial commerce, to the benefit of mother country and colonies alike. Therefore, Burke argued that the solution of the American controversy was easy. Let Britain . . . 'be content to bind America by laws of trade' because she had 'always done it'"[26] . The colonists had admitted many times that they did not mind paying a tariff that was meant to regulate trade. They thought that tariffs were necessary for the success of any country. Edmund Burke assumed that since the colonists had not objected to the external taxes used to regulate trade before that they would have no objection to them this time. He was partially correct. They were too upset about other things, such as the "creation of the Board of Customs Commissioners under British control, the sanction of searches by customs officials in homes as well as in stores and offices, and, most objectionable of all, the establishment of an American civil list from which money could be drawn for the payment of governors, judges, and other royal officials whose salaries had previously been in the hands of the colonial assemblies"[27] .

To placate the colonists as well as Parliament, Townshend said that the external "duties when collected would be applied to the support of civil government in the colonies and any residue would be sent to England"[28] . This was designed to halt any complaint that the money generated from these tariffs was going directly to the British Crown. There was, however, enough controversy in that promise alone to give rise to boycotts all over the colonies, but Townshend did not realize that, nor did anyone in Parliament. This idea was quite appealing to Parliament. If this plan worked, they were finally going to regain control over the British officials who had to live in the colonies, and the colonists would still be paying the salary of these men. Unfortunately, the colonists realized that if England was the one that was actually handing out the paychecks, so to speak, then they would loose to England what control they had over the officials.

The Townshend Acts that caused so much trouble in 1767 "proposed imposts on glass, paper, pasteboard, painters' supplies, and tea"[29] . They were imposed as the external taxes that Franklin had said would meet less opposition, but they were still opposed. The words of Lord Grenville several years before must have echoed in the minds of every man who had been present in Parliament at that time. He said, "I cannot understand the difference between external and internal taxes. They are the same in effect and differ only in name"[30] . How true those words were. This time, the colonists were so serious about not purchasing anything with any tax on it that went to the British government that they signed a pact amongst themselves stating that they would not purchase any goods coming to the colonies from England.

When these tariffs were protested in the colonies, Parliament began to feel as though "The colonial merchants demanded in effect free trade . . . or [at least] easy smuggling"[31] . Free trade was something that the mother country England did not even have. All Englishmen paid their taxes. There was no one on English soil, even on the Island of England, who was exempt from any of these taxes. Any sympathy in England for the colonists diminished significantly when they protested this set of laws along with all of the other ones as well. And the realization that they would never willingly pay their taxes to the British Crown turned out to be "the beginning of the end"[32] .

The people in England who had at first supported the stubbornness of the American colonists began to dislike them and their attempts to avoid their taxes at all costs. The reason for this could be blamed on the Townshend Acts as well. Through the Townshend Acts, the colonists were being pinched, and the English merchants were feeling the squeeze all the way across the Atlantic Ocean in a land 3000 miles away. "The boycott on British goods, particularly tea, threatened the livelihood of many English merchants. More and more sympathy for America was confined to those narrow circles of forward looking men or to professional politicians in opposition"[33] . But those "forward looking men and professional politicians" were beginning to get frustrated. The colonists were not allowing themselves to be taxed, the Townshend Acts were loosing support at home because of the economic impact in England, and Parliament was running out of ideas. The Townshend Acts were finally lifted, but the damage had already been done. It was just as Burke had feared when they were first introduced to Parliament. "He [had] prophesied correctly that the laws would" gain no revenue for England, but "only embitter the colonists"[34] .

One law did remain intact when the Townshend Acts were repealed, and that was the

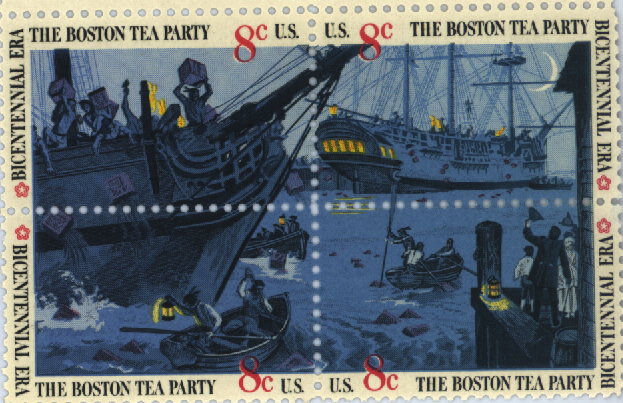

In an attempt to convince the colonists to adhere to the laws of Parliament yet again, the Tea Tax was lowered once more. Tea was now less expensive in the colonies that it was in England. "The tax on tea had been a continual irritant [in the colonies, and ] On December 16, 1773, the famous Boston Tea Party[36] expressed the dislike of British rule. All of the tea that had been left on the merchant ships was dumped into the Boston Harbor in response to this newly lowered tax on tea. Of course Parliament could not allow this type of rebellion, the destruction of property, to go unpunished, so a new set of laws was created.