FRtR > Documents > Brown v. Board of Education (1954) - background

Background information

Brown v. Board of Education (1954)

1954

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

(NAACP), the leading civil rights organization in the country, had never accepted the legitimacy of the "separate but equal" rule, and in the 1940s and 1950s had brought a series of cases designed to show that separate facilities did not meet the equality criterion. In McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents (1950), a unanimous Supreme Court had struck down University of Oklahoma rules that had permitted a black man to attend classes, but fenced him off from other students. That same day, the Court ruled in Sweatt v. Painter that a makeshift law school the state of Texas had created to avoid admitting blacks into the prestigious University of Texas Law School did not come anywhere close to being equal. Whatever else the justices knew about segregated facilities, they did know what made a good law school, and for the first time the Court ordered a black student admitted into a previously all-white school.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

(NAACP), the leading civil rights organization in the country, had never accepted the legitimacy of the "separate but equal" rule, and in the 1940s and 1950s had brought a series of cases designed to show that separate facilities did not meet the equality criterion. In McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents (1950), a unanimous Supreme Court had struck down University of Oklahoma rules that had permitted a black man to attend classes, but fenced him off from other students. That same day, the Court ruled in Sweatt v. Painter that a makeshift law school the state of Texas had created to avoid admitting blacks into the prestigious University of Texas Law School did not come anywhere close to being equal. Whatever else the justices knew about segregated facilities, they did know what made a good law school, and for the first time the Court ordered a black student admitted into a previously all-white school.

The opinion gave the NAACP and its chief legal counsel, Thurgood Marshall, the hope that the justices were finally ready to tackle the basic question of whether segregated facilities could ever in fact be equal. In 1952 the NAACP brought five cases before the Court specifically challenging the doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson. The issue that had hung fire ever since the Civil War now had to be faced

directly: what place would African Americans enjoy in the American polity?

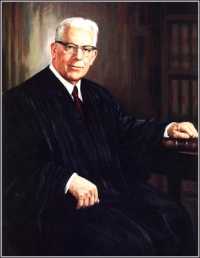

A number of reports indicate that the justices, while agreed that segregation was wrong, were divided over whether the Court had the power to overrule Plessy. They therefore set the cases down for reargument in 1953, specifically asking both sides to address particular issues. Then Chief Justice Vinson, who reportedly opposed reversing Plessy, unexpectedly died a few weeks before the reargument, and the new chief justice, Earl Warren, skillfully steered the Court to its unanimous and historic ruling on May 17, 1954.

A number of reports indicate that the justices, while agreed that segregation was wrong, were divided over whether the Court had the power to overrule Plessy. They therefore set the cases down for reargument in 1953, specifically asking both sides to address particular issues. Then Chief Justice Vinson, who reportedly opposed reversing Plessy, unexpectedly died a few weeks before the reargument, and the new chief justice, Earl Warren, skillfully steered the Court to its unanimous and historic ruling on May 17, 1954.

There is no question that the ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, which struck down racially enforced school segregation, is one of the

most important in American history. No nation committed to democracy could hope to achieve those ideals while keeping people of color in a legally imposed position of inferiority. But the decision also raised a number of questions about the authority of the Court and whether this opinion represents a judicial activism that, despite its inherently moral and democratic ruling, is nonetheless an abuse of judicial authority. Other critics have pointed to what they claim is

a lack of judicial neutrality or an overreliance on allegedly flawed social science findings.

But J. Harvie Wilkinson, who is now a federal circuit court judge, dismisses much of this criticism when he reminds us that Brown

But J. Harvie Wilkinson, who is now a federal circuit court judge, dismisses much of this criticism when he reminds us that Brown

"was humane, among the most humane moments in all our history. It was...a great political achievement, both in its uniting of the Court and in

the steady way it addressed the nation."

With this decision, the nation picked up where it had left the cause of equal protection more than eighty years earlier, and began its efforts to integrate fully the black minority into full partnership in the American polity.

For further reading:

- Richard Kluger, Simple Justice: The History of

Brown v. Board of Education and Black America's Struggle for Equality

(1976)

- Mark Tushnet, The NAACP's Strategy against Segregated

Education, 1925-1950 (1987)

- Daniel M. Berman, It Is So Ordered:

The Supreme Court Rules on School Segregation (1966).

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

(NAACP), the leading civil rights organization in the country, had never accepted the legitimacy of the "separate but equal" rule, and in the 1940s and 1950s had brought a series of cases designed to show that separate facilities did not meet the equality criterion. In McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents (1950), a unanimous Supreme Court had struck down University of Oklahoma rules that had permitted a black man to attend classes, but fenced him off from other students. That same day, the Court ruled in Sweatt v. Painter that a makeshift law school the state of Texas had created to avoid admitting blacks into the prestigious University of Texas Law School did not come anywhere close to being equal. Whatever else the justices knew about segregated facilities, they did know what made a good law school, and for the first time the Court ordered a black student admitted into a previously all-white school.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

(NAACP), the leading civil rights organization in the country, had never accepted the legitimacy of the "separate but equal" rule, and in the 1940s and 1950s had brought a series of cases designed to show that separate facilities did not meet the equality criterion. In McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents (1950), a unanimous Supreme Court had struck down University of Oklahoma rules that had permitted a black man to attend classes, but fenced him off from other students. That same day, the Court ruled in Sweatt v. Painter that a makeshift law school the state of Texas had created to avoid admitting blacks into the prestigious University of Texas Law School did not come anywhere close to being equal. Whatever else the justices knew about segregated facilities, they did know what made a good law school, and for the first time the Court ordered a black student admitted into a previously all-white school.

A number of reports indicate that the justices, while agreed that segregation was wrong, were divided over whether the Court had the power to overrule Plessy. They therefore set the cases down for reargument in 1953, specifically asking both sides to address particular issues. Then Chief Justice Vinson, who reportedly opposed reversing Plessy, unexpectedly died a few weeks before the reargument, and the new chief justice, Earl Warren, skillfully steered the Court to its unanimous and historic ruling on May 17, 1954.

A number of reports indicate that the justices, while agreed that segregation was wrong, were divided over whether the Court had the power to overrule Plessy. They therefore set the cases down for reargument in 1953, specifically asking both sides to address particular issues. Then Chief Justice Vinson, who reportedly opposed reversing Plessy, unexpectedly died a few weeks before the reargument, and the new chief justice, Earl Warren, skillfully steered the Court to its unanimous and historic ruling on May 17, 1954.

But J. Harvie Wilkinson, who is now a federal circuit court judge, dismisses much of this criticism when he reminds us that Brown

But J. Harvie Wilkinson, who is now a federal circuit court judge, dismisses much of this criticism when he reminds us that Brown