(Missionary Ridge Railroad Tunnel)

(Chattanooga and Cleveland Railroad Tunnel)

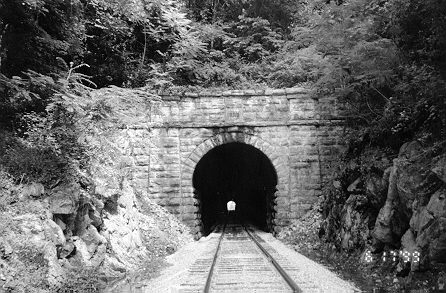

Western portal of tunnel (photograph by Peggy Nickell)

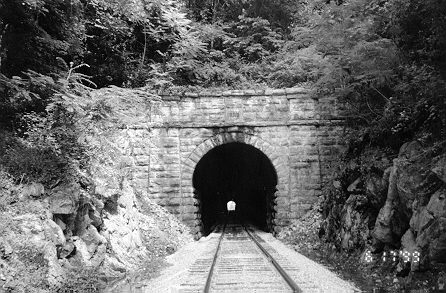

View of tunnel vicinity (photograph by Peggy Nickell)

Western portal of tunnel (photograph by Peggy Nickell)

View of tunnel vicinity (photograph by Peggy Nickell)

The Chattanooga, Harrison, Georgetown, and Charleston Railroad Tunnel was originally added to the National Register on August 24, 1978 (reference number 78002595). In November 1999, Abbey Christman and Peggy Nickell, under the guidance of Dr. Carroll Van West, at the MTSU Center for Historic Preservation, submitted additional documentation about this important structure, from which the following information has been extracted.

Location: Below North Crest Road, Chattanooga, Hamilton County

(code 056, zip code 37421)

Owner (private): Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum, 4119 Cromwell

Road, Chattanooga, TN 37421

Related multiple property listing: Chickamauga-Chattanooga

Civil War-Related Sites, 1863-1947

Number of resources: 1 contributing, 0 noncontributing (1

previously listed on National Register)

Historic functions: TRANSPORTATION=railroad; DEFENSE=battlefield

Current functions: RECREATION AND CULTURE=museum; TRANSPORTATION=railroad

Materials (walls): Brick, rock, limestone masonry

Narrative Description

The Chattanooga, Harrison, Georgetown, and Charleston Railroad Tunnel is located in eastern Chattanooga at the northern end of Missionary Ridge. It is also referred to as the Chattanooga and Cleveland Railroad Tunnel and the Missionary Ridge Railroad Tunnel. The Chattanooga, Harrison, Georgetown, and Charleston Railroad was formed to link Chattanooga to the East Tennessee and Georgia Railroad which ran through Cleveland, Tennessee. Construction on the tunnel began in 1856 and was completed in 1859. However, this date is controversial. According to Steve Freer of the Tennessee Railroad Museum, the tunnel was actually built between 1854 and 1856. The capstone located on the top western end of the railroad tunnel was misdated about 30 years ago. In 1859 the tunnel’s ownership was transferred to the East Tennessee and Georgia Railroad. In 1869 this line merged with the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad to become the East Tennessee, Virginia, and Georgia Railroad. In 1894 the East Tennessee, Virginia and Georgia Railroad became part of the Southern Railway. Currently the section of track that runs through the tunnel is used by the Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum.

The tunnel is cut through the northern end of Missionary Ridge. It is 980 feet long and its bore measures 12.5 feet (at its narrowest point) by 19 feet (at its lowest point, measured from roof to floor). The total volume of the tunnel is 210,000 feet. The tunnel portals were constructed in the shape of a horseshoe. Both portals are 17 feet high, 14 feet wide at the base, and 15.5 feet wide at the widest point.

The tunnel is composed of solid rock, brick, and masonry limestone from local quarries. The tunnel was originally hewn out of the rock and unlined. Brick and masonry stone lining was added to sections of the tunnel in c. 1870 as the East Tennessee, Virginia, and Georgia Railroad carried out needed repairs.

Starting at the western or Chattanooga end of the tunnel, there is a 98 foot lined section, 56 feet of solid rock, a 49 foot lined section, a 170 foot section of solid rock, and then a 611 foot lined section. The lined portions are mostly composed of limestone masonry sides with brick arched overheads. The stone was obtained from local quarries.

The Southern Railway inspected the tunnel in 1954 and noted the following structural problems: 1. The west portal has separated from the lining, leaving a gap of 1.5 inches which extends from the north spring line to a point halfway between the crown and the south spring line 2. There is a bulge in the lining, which measures three to four feet wide and projects one-half inch. The bulge is located fifty feet east of the west portal and extends from the spring line to the crown. Water seeps through this defect, but this condition appears to have stabilized. Except for these defects and the fact that a few portal stones have fallen, the tunnel appears to be in good condition.

In March 1960, it was proposed that the railroad tunnel now abandoned be used as bomb shelter. The railroad tunnel was denoted as being a “natural” location for a bomb shelter. No other evidence has been found to solidify if this proposal was accepted.

Statement of Significance

Applicable National Register Criteria: A, C

Areas of Significance: TRANSPORTATION, MILITARY, ENGINEERING

Period of Significance: 1856-1859, 1863

Significant dates: November 23-25, 1863

Narrative Statement of Significance

The Chattanooga, Harrison, Georgetown, and Charleston Railroad Tunnel was listed in the National Register of Historic Places on August 24, 1978, for its local significance to the engineering, military, and transportation history of Chattanooga and Hamilton County. This nomination contains additional documentation of the property’s significance in the engineering history of Chattanooga and Hamilton County as well as its military significance during the American Civil War. In that conflict, Chattanooga’s railroad network made the city strategically vital, with both sides vying for control of railroads. The tunnel not only was a significant component of the eastern railroad corridor, but also was a site of significant military action during the Battle of Missionary Ridge in November, 1863. The railroad tunnel is located on the site of a battle at the north end of Missionary Ridge, where Confederate forces under General Patrick Cleburne repulsed repeated attacks by Union forces under General William T. Sherman on November 25th. The original nomination stated that Cleburne’s Confederates actually entered the tunnel and used it during the fighting for concealment and fighting, but a careful reading of the official records of the battle do not offer confirmation that the tunnel was used in this manner. However, Confederate artillery took up a position on top of the tunnel during the fighting and used this position to good advantage in its defense of the Confederate line. The tunnel meets the registration requirements for Transportation-related properties listed in the Chickamauga-Chattanooga Civil War-Related Sites, 1863-1947 Multiple Property Nomination.

Engineering and transportation significance

African-American slaves, hired under contract for the project or owned outright by the railroad company, in tandem with white laborers constructed the tunnel between 1854 and 1856. It has been identified as one of the earliest, if not the earliest, railroad tunnel constructed in Tennessee. The laborers cut the bore by hand-drilling boles into the rock face. Then they filled these holes with black powder, ignited them and raced for safety. It was extremely dangerous and difficult work. The limestone they used in the construction came from local quarries and was set by hand. The tunnel portals were constructed in the shape of a horseshoe, and this is believed to be the only tunnel with a horseshoe portal in the state. When the tunnel was first constructed, the profession of engineering in the United States was still in its infancy, with the American Society of Civil Engineers having been founded just four years before in 1852. As a hard-rock tunnel of almost one thousand feet in length, the Missionary Ridge Tunnel was an engineering landmark when it opened to rail traffic and an important example of the use of slave labor in a southern industrial venture.

Once opened, the tunnel played a significant role in local transportation history by allowing Chattanooga to be tied to eastern railroad lines. The first railroad to arrive in Chattanooga came from the south, the State of Georgia’s Western & Atlantic Railroad in 1850. It was followed by a railroad from the north, the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad in 1854 and a railroad from the west, the Memphis and Charleston in 1857. The East Tennessee & Georgia, organized in 1847 and completed in 1855, ran from Knoxville, Tennessee to Dalton, Georgia, where it connected with the Western & Atlantic. This was soon linked to the East Tennessee & Virginia Railroad, the first railroad to cross the Appalachian Mountains. The railroad, however, did not pass through Chattanooga due to the difficult terrain. Goods and passengers bound for Chattanooga had to travel south to Dalton, Georgia and then transfer to the Western & Atlantic Railroad which took them north to Chattanooga. A shortcut was proposed between Chattanooga and Cleveland, Tennessee, on the East Tennessee & Georgia line. The Chattanooga, Harrison, and Cleveland Railroad was organized for this purpose in 1850 and was succeeded by the Chattanooga, Harrison, Georgetown, and Charleston Railroad. The first project was the construction of the line’s railroad tunnel between 1854 and 1856. Once the tunnel was completed, the construction of the rail line, “complicated and impeded by the many ridges which stood in the way,” began in 1856. It was completed in 1859 and taken over by the East Tennessee and Georgia Railroad. Chattanooga finally had its eastern railroad link. Together, the four major lines into the city brought commerce and industrial development to Chattanooga and made it an important transportation hub.

Military significance

The Chattanooga, Harrison, Georgetown, and Charleston Railroad Tunnel is also significant for its association with the Civil War campaign at Chattanooga in 1863. Confederate and Union forces were engaged in a fierce contest for control of the strategically vital Chattanooga, which was considered the gateway to the Deep South. Union strategists considered the control of the city essential to successfully launching an invasion into the heart of the Confederacy.

Confederate General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee defeated Union General William Rosecrans’ Army of the Cumberland in the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1863. Rosecrans’ forces, however, were able to retreat to Chattanooga where they took up a defensive position. Bragg’s Confederates then undertook a siege of the city, cutting off the major supply routes by rail, river, and road with their occupation of Missionary Ridge, Lookout Mountain, and Raccoon Mountain. In late October, the Union forces in Chattanooga, now under the command of Ulysses S. Grant, were able to reopen the Tennessee River to their supply boats and began to plan an assault on the Confederate positions. On November 24, 1863, a force under Union General Joseph Hooker successfully pushed the Confederates from Lookout Mountain and Union General William T. Sherman began his assault on the northern end of Missionary Ridge.

From his position, Sherman threatened the tracks of the Western & Atlantic which passed to the north of Missionary Ridge and the East Tennessee & Georgia Railroad which passed through Missionary Ridge via the C, H, G, & C tunnel. It was essential for the Confederates to hold on to the East Tennessee & Georgia line because it was their only link to the Confederate forces under General James Longstreet campaigning against Union General Ambrose Burnside in East Tennessee. Sherman’s force did not meet much resistance on the 24th, and they entrenched in the evening, hoping to move quickly along Missionary Ridge the next day, rolling up Bragg’s army.

Sherman’s force would face much greater resistance on the 25th. The Union force had mistakenly taken up a position on Billy Goat Hill, adjacent to the north end of Missionary Ridge rather than on the ridge itself. And during the night a Confederate force under the command of General Patrick Cleburne, which had been at Chickamauga Station awaiting transfer to East Tennessee, was recalled and sent to the north end of Missionary Ridge to protect the right flank of the Confederate army. Cleburne established a strong defensive position on Tunnel Hill, a 250-foot hill at the north end of Missionary Ridge, named for the C, H, G & C Railroad tunnel which runs just south of it. Cleburne would use the ridge’s rugged terrain of ravines and steep slopes to his advantage. His forces’ location on the hill meant only a small number of Federals could advance on them at a time, and Cleburne skillfully rebuffed these attacks in one of the most skillful defenses carried out by a Confederate general during the battles for Chattanooga.

The C, H, G & C Railroad tunnel was an important feature during the battle for the northern end of Missionary Ridge. The railroad tunnel was referenced in Union General Grant’s orders, which stated that after Sherman had crossed the Tennessee River near the mouth of the Chickamauga, he was “to secure the heights from the northern extremity to about the railroad tunnel.” The tunnel was an important landmark during the battle that was repeatedly referenced in the official reports of both Confederate and Union officers.

The tunnel also became a part of the battlefield. Cleburne placed

some of his artillery atop the C, H, G, & C railroad tunnel. In the

afternoon, as some of Cleburne’s troops moved down the hill to try to dislodge

the Union attackers, a fold in the hill led the Union soldiers to mistakenly

believe that the Confederates had come out of the railroad tunnel. A Texas

regiment charged down the hill, catching the flank of an Iowa regiment

by surprise. Lieutenant Samuel Byers of the Fifth Iowa recounted the attack:

Some cried, “Look to the tunnel! They’re coming through the tunnel.”

Sure enough, through a railway tunnel in the mountain the graycoats were

coming by the hundreds. They were flanking us completely.

“Stop them!” cried our colonel to those of us at the right. “Push

them back.” It was but the work of a few moments for four companies to

rise to their feet and run to the tunnel’s mouth, firing as they ran. Too

late! An enfilading fire was soon cutting them to pieces.

Byers was captured during the Confederate attack.

The railroad embankments of the East Tennessee and Georgia Railroad (outside the nominated boundaries) were held by Union Colonel John C. Loomis’s brigade in the afternoon and used for the limited shelter they provided.

Cleburne eventually abandoned his positions at and around the railroad tunnel as he pulled his troops southward to protect the rear of the Army of Tennessee as it was pushed off Missionary Ridge. In their retreat, the Confederates did not damage or block the tunnel and for the remainder of the war, Union commanders used the tunnel to ferry soldiers and supplies from the east to their campaign in Georgia.

After the war, ownership of the tunnel changed twice. In 1869 the East Tennessee & Georgia Railroad joined with the East Tennessee & Virginia Railroad to become the East Tennessee, Virginia & Georgia Railroad. In 1894 the East Tennessee, Virginia & Georgia Railroad became part of the Southern Railway Company, which operated the tunnel for the next sixty years.

The Southern Railway improved the track through the tunnel, but made no alterations in the tunnel itself, although it considered widening the tunnel in c. 1940. The Southern abandoned the tunnel in 1954 after the completion of the new Citico railroad yard meant that regular traffic would bypass the tunnel. In 1971, the Southern Railway donated the right-of-way through the tunnel to the Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum, a nonprofit organization dedicated to the preservation, restoration, and operation of locomotives and passenger equipment. The museum’s excursion trains currently use the line through the tunnel.

Major Bibliographic References

Abbazia, Patrick. The Chickamauga Campaign: December 1862- November 1863. New York: W. H. Smith Publishers, Inc., 1988.

Bowers, John. Chickamauga and Chattanooga: The Battles That Doomed the Confederacy. New York: Harper Collins, 1994.

Casteel, Bill. “Ridge Rail Tunnel Added To The National Register,” Chattanooga Times, 9 September 1978, Section C1.

Chattanooga Times. 18 September 1938, Section 6C

Chattanooga Times. “1850: Railroads Make Chattanooga Vital Junction,” 4 July 1976, p.9.

Chattanooga Times. “Col. Whiteside Led Legislative Efforts. 28 January 1957.

Collins, J.B. “Railway Tunnel, War Goal of 60’s, May Become Fall-Out Shelter Here,” Chattanooga Times, 14 March 1960.

Coniglio, John. “Tunnel Visions,” Chattanooga Times, 16 February 1999, Section D1.

Cozzens, Peter. The Shipwreck of Their Hopes: The Battles for Chattanooga. Urbana and Chicago: The University of Illinois Press, 1994.

________. This Terrible Sound: The Battle of Chickamauga. Urbana and Chicago: The University of Illinois Press, 1992.

Glass, Patrice Hobbs, “Actions and Engagements in McLemore’s Cove, September 1863,” Draft Report, Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park Civil War Sites Assessment.

Hattaway, Herman. Shades of Blue and Gray: An Introductory Military History of the Civil War. Columbia and London: University of Missouri Press, 1997.

Livingood, James W. A History of Hamilton County, Tennessee. Memphis: Memphis State University, 1981.

McDonough, James Lee. Chattanooga: A Death Grip on the Confederacy. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1984.

Pickenpaugh, Roger. Rescue By Rail: Troop Transfer and the Civil War in the West, 1863. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998.

Schmucker, LL.D., Samuel M. The History of the Civil War in the United

States: Its Cause, Origin, Progress and Conclusion. Chicago and

St. Louis: Zeigler, McCurdy & Company, 1865.

Sword, Wiley. Mountains Touched with Fire. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995.

Woodworth, Steven E. Six Armies in Tennessee: The Chickamauga and Chattanooga Campaigns. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998.

Geographical Data

Acreage of property: Appriximately 2 acres

UTM References:

1 16 660600 3881380

2 16 660260 3881500

![]() Return

to Surviving Engineered Structures

Return

to Surviving Engineered Structures

Last update: April 27, 2000