Originally published in the

Reproduced with permission.

Translated from the Dutch by Seamus Hamill-Keays, with a little help from his friends.

Belgium is one of the countries that

suffered greatly during the First World War. After the German invasion in 1914 most of the

country was taken over. Only a small

corner in the extreme south-west was not occupied. There, around Ypres, lay the scene of four long years of battle. There, one of

the greatest battles of history was fought. In 1917, the Allies launched a massive attack upon the German positions, and

the 3rd battle of Ypres commenced. British, Australians, New Zealanders, Canadians and two

Irish divisions;

the 36th Ulster Division and the 16th Irish Division. Whilst a serious conflict divided their homeland, the two Irish divisions were united side by side in the fight

against the Germans.

�Lone Tree Cemetery� announces a modern

green sign-board at the of the road. It has the shape of an arrow that points to the meadow of

the right. Nearby a gate in a wall allows entrance. The hinges grind loudly when the gate is

opened. With the help of a long rusty spring, it closes noisily. A grazing cow looks up,

startled. These days it's a coming and going to this small cemetery at

the back of a farm.

�Lone Tree Cemetery� announces a modern

green sign-board at the of the road. It has the shape of an arrow that points to the meadow of

the right. Nearby a gate in a wall allows entrance. The hinges grind loudly when the gate is

opened. With the help of a long rusty spring, it closes noisily. A grazing cow looks up,

startled. These days it's a coming and going to this small cemetery at

the back of a farm.

In fact there is no path to speak of through the pasture. It is lush, with trodden tracks.

The footprints are filled with water. For ten meters there is a muddy stone path. Next we

are guided by an untidy wooden fence. The way bends to the right and follows the edge of

an ink-black oval pond. Once formed by an explosion, it now only the harbour of a flotilla

of ducks , that lives here in serene peace.

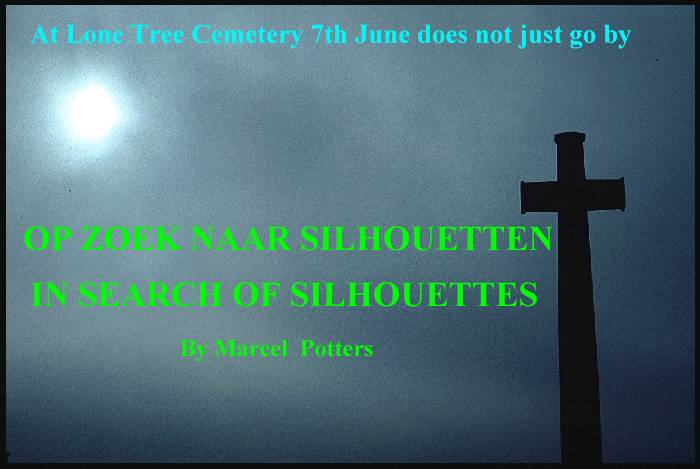

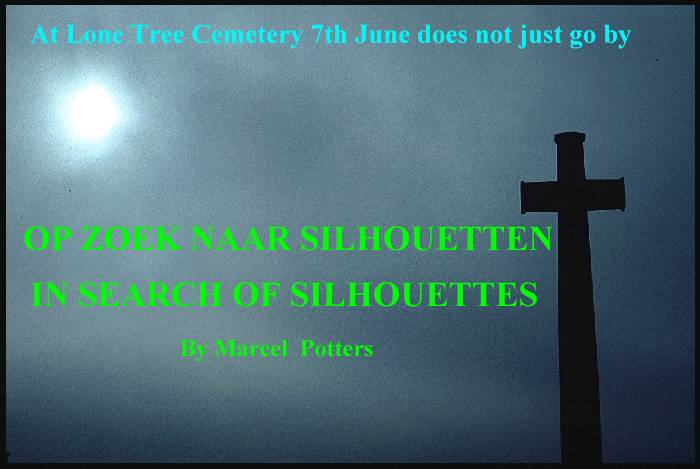

Lone Tree Cemetery. A green oasis in the middle of the West-Flemish scenery. It is still,

the only sound the wind that rustles the leaves of the willows around the water's edge. Round

about is a colourful patchwork quilt of fields -now lying fallow -with just here and there the

red of the roof of a farmhouse. In the distance the spire of the church in Wulverhem and the

stumpier one of the church in Nieuwkerke.

The cemetery is surrounded by a brick wall. Eighty-eight white stones stand on the closely-mown

grass. With a tall white cross standing several metres above the ground. There is a bronze

sword on the cross. The gravestones do not give much. The names, the unit, the day on which

they were killed, and the age. They were nearly all from the Royal Ulster Rifles, a

battalion of the 36th Ulster Division. The same date, 7 June 1917, is engraved on each stone.

Rifleman S. Parkinson, 7th June 1917, age 19

Rifleman R. Colvin , 7th June 1917, age 18

Rifleman Edmund Rooney, 7th June 1917, age 22

Rifleman F.T. Boulding, 7th June 1917, age 27

Rifleman S. Matier, 7th June 1917, age 21

It is said that the underground explosion tinkled the crystal chandeliers in Buckingham Palace

in London. In Lille, some tens of kilometers behind the front, the series of explosions caused panic.

An earthquake?

The earth leapt to the skies, the morning of the Big Bang, 7 June 1917. What came out of the

higher ground situated south of Ypres, was an inferno of stone, steel and above all, mud.

The unsuspecting Germans, for years lords and masters of the strategically situated Messines

Ridge, were pulverised in one mighty thunderclap.

Observers on the Allied side could scarcely believe their eyes. One of the British

tunnelers said, "The earth seemed to open and rise into the air. Flames shot upwards,

everywhere was dust and smoke. And everything that went up eventually fell back to earth."

Momentarily the forward troops stood rooted to the ground. "None of us'" said one later on,

"had ever seen anything like it. It was a mass of fire. The whole world seemed to explode."

The next moment, the whole front, static since November 1914, burst in movement. The men

of the 36th Ulster Division stormed out of their trenches. This was a tableau they had so

often performed in the previous three years during the First World War, since the first day,

when the Germans invaded France and Belgium, until the summer of 1917, the eve of the Third

Battle of Ypres. A throng of young fellows, many not yet 20 years old and many with a family,

fired, like politicians and commanders, with the conviction that one decisive trick might

bring the Great War to an end.

When the Irishmen conquered the Messines Ridge, they gained

an outstanding advantage. For months, work had progressed on the Allied side on tunnels,

varying in length from 65 to 700 metres. They reached right under the German emplacements,

which caused death and destruction in this sector. Through their positions above the flat Flemish

landscape, they could follow every detail of movements of the British army around Ypres.

With field-guns, howitzers and mortars they bombarded strong points. The British did not even

try to storm the ridge- the Germans, with barbed-wire, machine-gun

nests and concrete, had turned it into a fortress.

Perilious

The digging of tunnels was a perilious occupation although the heavy clay subsoil was ideal

for this sort of work. When this work was completed the explosive could be laid. Only one of

the tunnels was discovered by the Germans and destroyed; two others in the southern sector of

this front did not explode.

The Ulstermen went forwards, in the direction of Spanbroekmolen, a short distance beyond.

On the left flank the 16th Irish Division was also moving up. It was about 3 a.m. on 7th June

and pitch dark. Machine-guns rattled. Although the mines, in total a half million

kilogrammes of explosive, had made the area resemble a moonscape, there were certainly Germans

still alive. They fired on the advancing Irish. Many fell wounded or fatally injured.

Some say it was half a minute, others maintain that it happened 15 seconds

late, but anyhow fate struck on that moment. One of the underground mines, that near

Spanbroekmolen, exploded a bit later than the others. The consequences were horrific.

The foremost Irish troops, that at that moment who at that point had made steady progress,

disappeared there and then. Others would be buried under the earth and the debris that came down from

the explosion.

Mass of Fire

Lieutenant T Witherow, of the Royal Irish Rifles, : "We�d made it through the machine-gun fire

and had almost got to the German positions, when a terrible thing happened that nearly put an

end to my fighting days. All of a sudden the earth seemed to open and belch forth a great mass

of flame. There was a deafening noise and the whole thing went up in the air, a huge mass of

earth and stone. We were all thrown violently to the ground and debris began to rain down on

us. Luckily only soft earth fell on me, but the Lance-Corporal, one of my best section

commanders, was killed by a brick. It struck him square on the head as he lay by my side.

A few more seconds and we would have gone up with the mine."

The Times, Friday 8th June 1917

The following telegraphic dispatches were

received from General Headquarters in France yesterday:We attacked at 03.10 this morning the

German positions on the Messines-Wystschaete Ridge on a front of over nine miles. We have

everywhere captured our first objectives and further progress is reported to be satisfactory

along the whole front of the attack. Numbers of prisoners are reported to be already reaching

collecting stations.

On the left of the track, right opposite

Lone Tree Cemetery, is a substantial and overgrown unnatural hillock. From the road you can

only see a tangled maze of brushwood, of wild roses and brambles. Trees also , mainly willow,

stand close together. A slippery path leads up behind the undergrowth. There is no hilltop, but

the surface of a lake, one hundred and thirty meters wide, and doubtless very deep.

On the left of the track, right opposite

Lone Tree Cemetery, is a substantial and overgrown unnatural hillock. From the road you can

only see a tangled maze of brushwood, of wild roses and brambles. Trees also , mainly willow,

stand close together. A slippery path leads up behind the undergrowth. There is no hilltop, but

the surface of a lake, one hundred and thirty meters wide, and doubtless very deep.

This is Lone Tree Crater. In 1917 it was created by the mine that killed the Irish.

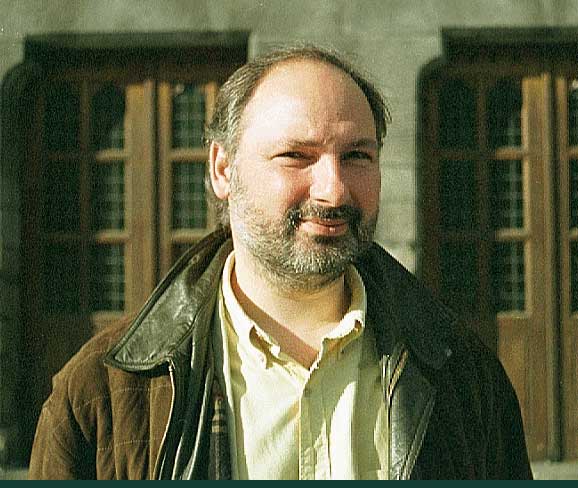

"Last year the little pond was all deep red, says Piet Chielens (42), co-ordinator of the

�In Flanders Fields� Museum.

He stands on the rim of the crater and gestures towards the water."It was a kind of duck-weed

that had become diseased. A weird sight. They removed it later."

"Last year the little pond was all deep red, says Piet Chielens (42), co-ordinator of the

�In Flanders Fields� Museum.

He stands on the rim of the crater and gestures towards the water."It was a kind of duck-weed

that had become diseased. A weird sight. They removed it later."

He knows the area like the back of his hand. A journey through it is to him like a journey

through time. That eighty years on, it completely tests his comprehension, brings him no

comfort. The Front is still in his head. " I don�t have to imagine things," is his philisophy,

" the reality was worse than all possible fantasies."

The crater rim offers a perfect view of the area over which the two Irish Divisions had

to advance. There, below, lay the divisional area of the 36th Ulster Division, created from the

Ulster Volunteers. Established in 1912 by Edward Carson, to defend Protestant interests

against the [zogheten] Home Rule, the introduction of Ireland's own parliament and government.

And, there, beyond, advanced the 16th Irish Division, a formation from the south of Ireland,

brought together by the leader of the Irish Party John Redmond. He was, in every respect,

the protagonist of Carson, and was the promoter of Home Rule. About 50000 Catholic Irishmen,

from north and south, responded upon hearing upon Redmond's call to arms and joined the

division. Before Ypres, Ulstermen and Irishmen had already suffered terribly in the Somme

offensive, during the summer of 1916.

Slaughter.

And whilst Ireland itself was sufering the fire and flame of conflict after the

Easter Uprising, Protestants and Catholics fought shoulder to shoulder. On 16th August,

during the 3rd Battle of Ypres, occured a slaughter one can scarcely believe.

Both Irish divisions struggled in a battlefield that, through incessant rain, had become a

stinking foul morass. Sustained bombardment and shelling had so churned up the earth that

the landscape had a ghostly and ghastly appearance. Deep shell-holes everywhere, overlapping one

another, filled with water and forming deadly traps for the soldiers of Erin who so

steadfastly advanced.

In the year 1998 these events are scarcely understandable. Some Westhoekers, as the

residents of this small part of West-Flanders are known, have shut themselves off from them.

They can hardly hide from them. In the surroundings of Ypres alone there are 140 cemeteries

of the Great War, last resting places of the half million soldiers, - Allied and German who

lost their lives in this area. The numbers defy imagination.

Chielens : "I have in my office at the museum an old photograph from 1921 or so, a farmer is

ploughing his field. At the back you can see a half-buried tank, to the front an isolated grave.

The farmer is leading his horse and plough around these �obstacles�. That picture says a lot.

The people who lived here had to go on, they had to make a living among these gruesome relicts.

This might be a reason why a good number of local people still seem a bit withdrawn,

just minding their own business."

The story of the Irish soldiers in the Ypres salient is first and foremost a story of

solidarity among brothers in arms. The quarrels at home were overtaken by this much

bigger worldwide struggle. "They were comrades in arms. When on June 7th 1917 William

Redmond was wounded, it seemed almost natural that he was taken back by stretcher bearers

from the Ulster Division. Major Redmond was the brother of John Redmond, a champion of

home rule for Ireland. Yet this catholic figure was brought back to an Aid Post of the

Ulstermen. They spared no effort to save his life, but unsuccessfully.

In the days after the sorrow among protestants was just as great as among catholics."

Lone Tree Cemetery and its crater; Just a mere 15 seconds in a four year long war. " The

cemetery and the crater are one, as is this whole area. When you stand here there�s no way

that you can reduce this war to a map with frontlines and coloured arrows that indicate troop

movements. You can�t get much nearer to the reality of it all. In this sunset, you find

yourself looking out for human shapes and shadows, the silhouettes of those who fought

and died here."

The Times, Friday 8th June 1917

In the capture of the ridge, both north and south Irishmen have their share. Northerners and

Southerners, Protestant and Catholic troops, fought alongside of one another and, whatever may

be party feeling at home, it is as well to know that the feeling between the two bodies here is

most cordial. The Southern Irishmen recently presented a cup for competition between the various

companies of the Northern force, and of late there has been swearing of the utmost rivalry as to which

would get to the top of the Messines Ridge first. I do not yet know who did, but I have no doubt

that both were first in good Irish fashion

Eventually the 3rd Battle of Ypres ended on 6th November 1917 when the Canadians captured the

village of Passchendaele. And yet the war in this part was not at an end. In the Spring of 1918

the Germans made a last desperate effort to take Ypres, in vain although the ground so bloodily captured by the Irish was lost. In the autumn the Allies struck back and finally drove the enemy from this sphere of operations.

Afterwards remained the hundreds of thousands of dead, the many tonnes of steel and iron as

well as an enormous amount of munitions. After the war, farmers paid young men to dig two

spades depth in their fields. Many hundreds came into contact with explosive and were paid for

this work with death. A mine, that had not gone off in 1917, exploded at last in 1955, in a

heavy thunderstorm.

"There�s still one out there somewhere," says Piet Chielens,"in a not too precisely-known place.

They say they�re going to look for it shortly. "

The events in this region around Ypres have changed him fundamentally, his own words. " I guess

I�ve become a pacifist and even more an internationalist because of that war. In my tiny little

village, young people from 14 different nationalities are buried. As a child I always thought :

why did they only come here to die. Why didn�t they stay on to live, so that I could have

a chance to meet them ?"

Each grave in Lone Tree Cemetery has its own tragedy. "But there are almost 600,000 such

tragedies in this area. We have in the museum a picture of a soldier in the Leinsters, who

was shot in No Man�s Land.It happened just a few hundred yards back there. The bullet had

gone through his wallet. In the wallet were his letters; letters and cards from his wife

and daughter. �I�m quite well�-cards to his mother and other relatives, that he didn�t have

time to send off. Of each document the left top corner is torn by the bullet.

When we were installing the objects in the museum, I wanted this wallet on display. When

we arranged the letters, so that people could see well, it was almost too much. His grave is

just down the road. And so each grave, each name on a memorial represents the same tragedy

to families throughout the world. And it doesn�t really matter if this was Ieper 1917 or Kosovo

1998. "

He looks at the little Irish cemetery down the slope. " As long as this remains here, the war

remains here. In all its horror. And with that, the hope on a better future for all people."

Music:"Largo: Dvorak"

Return to 16th Irish Division Website

�Lone Tree Cemetery� announces a modern

green sign-board at the of the road. It has the shape of an arrow that points to the meadow of

the right. Nearby a gate in a wall allows entrance. The hinges grind loudly when the gate is

opened. With the help of a long rusty spring, it closes noisily. A grazing cow looks up,

startled. These days it's a coming and going to this small cemetery at

the back of a farm.

�Lone Tree Cemetery� announces a modern

green sign-board at the of the road. It has the shape of an arrow that points to the meadow of

the right. Nearby a gate in a wall allows entrance. The hinges grind loudly when the gate is

opened. With the help of a long rusty spring, it closes noisily. A grazing cow looks up,

startled. These days it's a coming and going to this small cemetery at

the back of a farm.

On the left of the track, right opposite

Lone Tree Cemetery, is a substantial and overgrown unnatural hillock. From the road you can

only see a tangled maze of brushwood, of wild roses and brambles. Trees also , mainly willow,

stand close together. A slippery path leads up behind the undergrowth. There is no hilltop, but

the surface of a lake, one hundred and thirty meters wide, and doubtless very deep.

On the left of the track, right opposite

Lone Tree Cemetery, is a substantial and overgrown unnatural hillock. From the road you can

only see a tangled maze of brushwood, of wild roses and brambles. Trees also , mainly willow,

stand close together. A slippery path leads up behind the undergrowth. There is no hilltop, but

the surface of a lake, one hundred and thirty meters wide, and doubtless very deep.

"Last year the little pond was all deep red, says Piet Chielens (42), co-ordinator of the

"Last year the little pond was all deep red, says Piet Chielens (42), co-ordinator of the