|

|

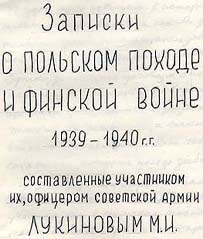

Notes on the Polish Campaign and the War with Finland in 1939-1940 Written by their participant, a Soviet Army officer, M. I. Lukinov |

The Polish and Finnish events of 1939-1940 are little covered in history and literature. It's as if they were eclipsed by the immensity of the Patriotic War, which followed them. Nevertheless, the signing of the non-aggression pact with Germany, temporary destruction and division of pan Poland (Pan is the Polish word for master/mister, in this way the communists declared that only the Polish ruling class, not the people, were the enemy. Other examples include: fascist Germany, samurai Japan, boyar Romania - trans.) and also the war with Finland were events which cannot be forgotten. The author of these lines had the honor to directly participate in both the Polish campaign and the fighting against the White Finns (this term comes from the Civil War, in which the Finns sided with the Whites against the Reds - trans.), and has taken upon himself to describe everything he lived through, experienced, and saw.

It was the uneasy 1939. There was war in Europe, which threatened to draw near our borders. I was only 32 and could, as a reserve officer, be mobilized into the army any day. But somehow I didn't want to believe that there would be war. I worked, as usual, as an engineer in my Rosspromproekt Institute designing construction materials factories. I had been promised a vacation in the end of the summer of 1939, which I was going to spend in the south, on the coast of the gentle Black Sea. But my plans were ruined by a military commissariat summons: "Come with personal belongings." That was a shock. I ran to our Bauman District Military Commissariat and started asking for permission to go on vacation first, and then "come with belongings." They told me strictly: "What vacation? You have been mobilized. Don't you know that the war is starting?!" What war? With whom? I couldn't understand. The next day I was already riding on the Moscow-Kiev train "with belongings."

Mikhail Lukinov, January 1939. |

In those times trains were comparatively slow and were pulled by steam locomotives. The cars were equipped with three rows of wooden bunks painted with green oil paint. At the stations, the passengers ran out for hot water with tin kettles and the train's departures were signaled by manually ringing a bell. Recent, but already archaic times.

The car was overcrowded and, in order to sleep, I had to climb up onto the third baggage shelf, and even tie myself to a heating pipe with a belt so that I wouldn't fall off because of rocking. A group of us officers was sent from Kiev to Belaya Tserkov', known to us from Pushkin's "Poltava". But we didn't find a "quiet Ukrainian night" there. On the contrary, there was a horrible bustle around us. A rifle (infantry) division was being hastily formed from reservist Ukrainian "uncles". As an artillery man, I was put into the regimental battery of the 306th Rifle Regiment. An artillery man, and into an infantry regiment! It was hard, but what could I do? I had to take the black tabs off my uniform, and saw the red ones on, even if with crossed cannons. There were nine officers in the battery, all of them, except me, a reservist, were regulars, and at first I didn't even have any defined duties. I was something like an aide-de-camp for the battery commander. In those times the junior officers in the army were not distinguished by high culture. Even people with secondary education were rare among them. They were men who remained to serve beyond their term, served for several years, who were taught direct and indirect fire in various schools and training classes. But they knew the general military order and discipline very well. Overall, they were nice sociable guys, mostly junior lieutenants. Having seen that even though I had two cubes on my tabs (a lieutenant), but wasn't a snob, they accepted me into their family. The battery commander was also from the same stock, but already with three cubes (a senior lieutenant). In order to make himself look like a commander, he gave himself airs and estranged himself from us. His physiognomy was impenetrable, horse-like, always stony, badly damaged by smallpox. He feared any kind of familiarity because he saw it as undermining discipline. He treated me with guarded reserve, seeing an "alien" in me, an educated one at that. We also had an artillery chief of the regiment, who was in charge of our artillery and a mortar battery. He was more favorably disposed toward me. We received 76mm guns, but short barreled ones, model 1927, which were pulled by two pairs of horses. We also received horses. I got a huge gray riding horse named Doll. We started forming platoons, rode out into the field, fired training shots, trained the soldiers. The regiment commander was pressing us to hurry, everything was being done hastily. We hadn't finished forming when we received the order to march. A familiar command sounded: "Form a marching column! Platoon HQ in the lead! Forward march!" And we set out. Where? Why? Only the superiors knew about that. Or maybe, even they didn't know? Soon we realized that we were being led westward, to the Polish border.

|

Meanwhile, the political developments continued. Germany attacked Poland and captured main Polish lands. Our government had signed a non-aggression pact with Germany. Molotov, in his well-known speech, called Poland an "ugly child of the Versailles Treaty." And it was decided to liberate Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia, seized by the pan Poland in the past. The Soviet forces had to be quickly thrown forward to the dividing demarcation line with Germany. By that time we had already been pulled close to the Polish territory; and now, raised by an alarm, we started crossing this, now former, border.

The infantry units of our regiment marched in front, and we pulled our guns behind them. I remember a striped border post with a Polish eagle that had been knocked to the ground, a Polish border village of accurate white houses of some unfamiliar medieval architecture, with a cathedral. The Poles watched our invasion gloomily and apprehensively. Really, what were they thinking?

Dirt roads and poor Ukrainian villages with straw roofs and barefoot peasants laid beyond the immaculate Polish border village, obviously a window dressing. The Ukrainians lived badly under the pans' oppression. We found out about all of that later, when we were billeted in a Ukrainian village. And so, we were advancing over the former Polish land to the west. The first night stop. A poor Ukrainian house: dirt floor, filth, roaches, half-naked children. I started talking to one little girl of maybe 10 years, dug 20 kopecks out of my pocket and gave them to her as a keepsake. She was struck by such a rich gift and yelled: "Mommy, I have twenty kopecks!" Apparently, she held such an amount of money for the first time in her life.

Soon we received an order to load all the regiment's unmounted soldiers into trucks and hastily throw them to the demarcation line that cut Poland in half. The horse transport, supply trains, and guns were supposed to continue the march at their speed. We formed a detachment from unmounted battery men, which was supposed to ide with the infantry. Of course, I was put in charge of it. At night, on the highway, I was stopping the trucks with infantry and was fitting my soldiers in there with curses. I got on the last truck. We traveled for several days through the entire Western Ukraine in this manner. There were many meetings and impressions which are, unfortunately, gone from my memory.

I remember how we entered some town and stopped in the middle of the market. The vendors with trays ran to the trucks from all sides, offering us their wares. (It must be noted that during the entry of our troops into the former Polish territory a practical currency exchange rate was established: one zloty was made equal to one ruble.) One of the vendors brought a tray with pierogi to our truck. An infantryman sitting next to me asked about the price. "Three kopecks, pan, can't sell them cheaper, there is war now." The soldier took a green three ruble paper out his pocket and said: "Give me a hundred." "Why do you need so many?" I asked. "It's OK, comrade lieutenant, I'll find use for them." He really did use all of them. He ate the entire hundred, despite the envious glances and requests of his comrades. A real Ukrainian kulak.

The traders immediately understood the nature of the market and in fifteen minutes the pierogies already cost 15 kopecks. We were mainly fed wheat porridge, black bread, and tea from field kitchens. Some technical unit was following us, they had rice, white bread, and cocoa. Nothing you could do: we were infantry, first in advance and last in supply. Once, late in the day, we stopped for the night in some town. The trucks were driven into a schoolyard, and we settled until morning in the classrooms. I was very hungry. I took two of my soldiers (the officers were prohibited from walking alone) and went to look for some restaurant. We soon saw some small bar in a basement, where the windows were brightly lit and music was playing. When we entered the hall, the three of us in army coats, helmets, boots with spurs, and weapons, a slight commotion occurred. The band stopped playing. Some customers got up in fear. They saw Soviets for the first time in their lives. I greeted everyone politely and asked the musicians to continue playing. We were being examined with curiosity. The owner stood behind the bar, a fat man in an unbuttoned vest, with a cigarette in his mouth. I felt like I was in the middle of a shoot of some pre-revolutionary film. "Vodka, schnapps?" - the fat man asked me. "No, " - I replied - "three coffees and three sandwiches." "It was 12 at night according to my watch, but a large round clock behind the bar showed only 10. I didn't immediately realize the possible difference in time and told the owner with surprise that it was 12 now. He smiled, took his cigarette butt out of his mouth, and said proudly, gesturing in my direction: "We're on European time." It had to be seen the way he said it: "We are Europe!" In the miserable pan Poland the clock was on London time. "Now you'll have to move your clock to the Moscow time," - I replied. The owner of the bar shrugged, as if saying "We'll see." Having finished coffee and settled the tab, we left those "Europeans".

Here I'll allow myself a short digression and recall another anecdote, which happened many years after the Patriotic war, when the Polish state was reestablished and the Soviet Marshal Rokossovskiy, an ethnic Pole, was appointed the commander of the Polish Army. He arrived to Poland. In the beginning he was shown Warsaw, and one of the Polish generals asked: "Pan marshal, how do you like Europe?" The marshal replied: "Apparently, you don't know geography well."

We marched for the last stages of our journey. Again there were Ukrainian villages and small towns with Jewish and Polish population. Germans had already been there. But before pulling back, they pillaged. But they were a cultured nation, that's why they didn't burst into stores, threatening with their guns. They robbed in a "cultured" way. They entered stores, selected the best merchandise, ordered it to be packed ("Raskep, raskep"), and then took their "purchases" and left: "The Russians are coming behind us, they'll pay for everything."

I entered one of the stores to buy some small thing. The textiles were spread on the counter, they had been looked at by some infantry soldiers before me. I stroked the fabric and suddenly felt that there was some object under it on the counter. A rifle was lying under the fabric, it had been forgotten by these Ukrainian "uncles". I had to take this rifle with me.

Red Army soldiers. Luga, 1938

|

We finally reached the demarcation line, which followed the Bug River. We could see how the shovels flashed on the other side of the river. Those were Germans fortifying their positions and digging trenches. The river was not very wide in that spot, and temporary bridges were thrown over to the other side. Some silhouettes could be seen using them to cross the river: some to our side, others from us. It's strange that no one hindered that in the first days. One of our officers told us that he saw some man approach the German guard on the other side and point that he needed to get to the other, that is our, side. The guard simply kicked him in the ass, and the man ran to us over the bridge. That was during the day, running back and forth intensified after dark. Yells and shooting started.

They said that one of our guards, a Ukrainian "uncle", kept muttering while standing guard near the bridge: "Let a good man come to us, let a bad man leave."

In three-four days after our arrival, our border guards in green caps came, with dogs, and closed this temporary border tightly. We were pulled several kilometers back from the demarcation line, but we were often raised by an alarm at night even there. One night some two men were stealing through to the German side. There was a small lake not far from our disposition, where a local fisherman usually fished. There were remains of barbed wire barriers in front of that lake. Those two approached the lake in the dark, and thinking that it was Bug before them, they tore through the barbed wire and started swimming. And got lost. Started drowning. The fisherman heard their screams, came with his boat, and started pulling them out. One of them asked in Polish: "Is this the German side?" The fisherman said: "Yes." Hauled them in and brought them almost suffocated to his house. Because of them we were again raised by an alarm in the night, thinking that there were more than two of these defectors. In the morning I saw how these drowned men were loaded into a car to send them where they belonged. They turned out to be Polish officers who ran away from a POW camp.

It was unquiet on the border. During nighttime, someone from our side wrote intricate lines on the dark low clouds with a flashlight beam. They were replied to from the other side in the similar fashion. And we couldn't catch anyone. German officers came, supposedly to search for buried remains of their countrymen, but, in reality, to spy on our dispositions and what forces we had. But we also drove them so they wouldn't see anything they weren't supposed to.

Soon our division was pulled back far into the rear. The regiment was quartered in a small dirty town of Staryy Sambor. Mainly Jews lived there, traders and craftsmen, who serviced the Ukrainian villages. But there was no room for our battery with its guns, supply wagons, and horses even in Staryy Sambor. We were allocated a village of Blazhow, which was separated from Staryy Sambor by another 7-8 km of dirt roads. In order to decide on our quarters, the superiors ordered me to go into the village and make a schematic map of it location. Our sergeant major came with me on his supply business. We rode horses.

The village turned out to be a large, spread out one. It had a Uniate church and a folwark - a small landlord estate, whose owner, a Pole, ran away to the Germans. I made rough notes and, after returning to our battery, drafted the map cleanly with colored pencils, labeled everything, even showed some buildings in perspective. The superiors were happy, but didn't show it. They couldn't spoil their subordinates. That could make them conceited. But the sergeant major (as I was told), while sitting near a fire at night, in his company, told everyone with surprise that the lieutenant had simply passed through the village making some marks on a piece of paper, and then drew such a map: "This man, guys, was not a herder back home."

Soon we moved to Blazhow. We chose the folwark as the center of our disposition and placed the guns in its yard. The officers were quartered in the landlord's house, and soldiers - in surrounding peasant villages. We put the horses in the folwark's farm structures. The landlord's house had been completely pillaged by the Germans, and then peasants, so that only naked walls remained there. Only the former office contained a large desk with empty drawers. The desk wasn't carried away because it didn't fit through the narrow doors of the office. At first we had to make do with straw instead of furniture, which replaced both chairs and beds for us. We put our field phone on the only desk, its line was laid to the regiment HQ, in Staryy Sambor.

It was unquiet. Some bandits would sometimes shoot during the night. Someone would cut our communications wire, and then the battery was raised by an alarm in the night. We took up all-round defense in the dark around the folwark, waiting for a possible attack. But dawn came, and our apprehensions evaporated.

But we were warned from the regiment's HQ that we had to be vigilant, that there were cases when Soviet soldiers were killed in dark alleys, stabbed in barber shops, and so on. Being quartered in a Ukrainian village, we saw for ourselves how poorly the western Ukrainians lived in pan Poland. Only Poles had all the rights in that country. Only they could work in government service. A Ukrainian couldn't even be a simple laborer on road construction - that was government work. A Ukrainian could become a Pole, but for that he had to change faith and become a Catholic. The measures had been taken for gradual transfer of Ukrainians into Catholicism. The Orthodox faith was substituted by Uniate, something in the middle between Orthodoxy and Catholicism. Ukrainians were pressed by taxes. There was even a tax from each chimney, and after crossing the border we were surprised that houses stood without chimneys. The smoke from stoves was released straight into the attic under the roof. Fires were frequent.

We were sometimes asked if it was allowed to build chimneys now. We replied that not only was it allowed, it was necessary. In the late autumn the peasants would walk to church barefoot. They cleaned their dirty feet on the grass in front of the church, put their boots on, and entered. When leaving, they took their boots off and hung them around their necks. One pair of boots served a peasant all his life, and when dying, he passed them on to his son. There was a post office with a telegraph in the village, which now stood idle. But there still remained a telegraphist - a Pole, a very beautiful and proud girl. There was always a line of suitors around her. Not only our soldiers and sergeants ran there, but some of our single officers as well. Trouble was brewing among suitors. They said that someone even asked the superiors to marry that beauty. But all that abruptly came to an end in a most unexpected way.

One night, while on duty near the field phone, one of our signalers noticed that one of the desk's drawers was shorter than the others. Why? It turned out that there was a secret drawer on the back side of the desk, the one turned to the wall. There was worthless Polish money and a photo album in it. The photographs showed how the beautiful telegraphist had merrily spent her time with the folwark's owner. In some pictures, she danced naked on a table full of bottles, in others, she laid embraced by some moustached men, and so on. The album started being passed around between soldiers. Some soldier in love started a row with the girl, and she quickly disappeared from the village. The battery commander took the album away from the soldiers and lost it somewhere. I didn't see the album.

A night of bonding with the local population was organized. The entire village of Blazhow assembled in some large and spacious house. Our politruk (political officer) made a speech about the end of pan Poland, about the Red Army's mission of liberation. The local priest replied in the name of the population, he thanked us for liberating them and noted that "we have same blood, same faith." Then the local band consisting of a violin, a bag pipe, and a drum started playing, dances began. The people started asking us questions about life in the Soviet Union, about which they had only had wild rumors in Poland. Our sergeant major distinguished himself there. In those times, we officers were dressed very modestly, in the same camouflage tunics as the soldiers, the only difference was that our collar tabs had cubes on them and red cloth "angles" were sawed to our sleeves. But our sergeant major wore a cloth uniform encircled with yellow squeaky belts. And he pinned, besides the rectangles, golden "angles" which had been removed from the uniform long ago, to his collar tabs. In the eyes of the population he was the chief commander, they asked him the questions. Girls asked him if it was true that we didn't have weddings in Russia anymore, that they were abolished, and everyone lived with whoever they liked. The sergeant major replied pompously: "People speak of different things, but lice infested ones always speak about a bath." Of course, there was laughter and embarrassment.

One time in Staryy Sambor I went to a small private metal workshop to order a cleaning rod for my handgun and met the shop owner's sisters, two Jewish girls. They had graduated from a Polish school in Novyy Sambor and were very interested in the Soviet Union. They dreamed of going to the Union to attend a university, "where, they say, it's free." When I was in Staryy Sambor, I would visit these two sisters and teach them Russian, which seemed easy and understandable to them. But once, to prove that it was far from truth, I read the opening of "Yevgeniy Onegin" to them, which they, of course, couldn't understand. These poor girls probably perished in 1941, when Western Ukraine was captured by Germans, who killed all Jews there.

Sometimes I needed to visit Novyy Sambor on business. It was a pretty decent Polish town, which had a restaurant and good stores. Once I went into a haberdashery and asked them to show me some ties. The store's owner, winking at a Polish woman behind me, as if saying "what would this barbarian in a gray greatcoat understand about ties", gave me a box with some cheap stuff for peasants. I pushed the box away and asked her to show me something better. The owner's face registered surprise when this barbarian picked out and bought a dozen of the most elegant and beautiful ties, which served me a long time after that.

Mikhail Lukinov, 1939

|

The streets were full of some men who offered to sell watches, razors, chocolate, socks, and other merchandise to the Soviet military personnel. One of these hustlers glued himself to me, offering suit lengths. I kept waving him away, but he wouldn't leave me alone. At that time blue Boston suits were popular in Moscow. I finally asked that man if he had blue Boston. "I have it, pan comrade, I have it." And offered to follow him. He led me through some intercommunicating yards, from one to another, so that I lost direction, didn't know where the main street of the town was. He descended into some basement in one of the yards, from that basement he led me to another one, and asked me to wait. I looked around. It was some concrete bunker without windows. A light bulb near the ceiling was barely lit. Suddenly, beyond the door through which that man had disappeared, I heard slight metallic clanking, as if someone was loading a rifle, opening and closing the bolt. I unbuttoned my holster and hurried outside into the yard. I stopped there to wait for further developments. But everything was quiet, and the seller of Boston didn't appear. I had to get out of the labyrinth of the yards to the main street, where it was safer. I still don't know if I avoided mortal danger or simply left myself without a blue Boston suit.

The pan Poland was falling apart. Polish currency was living its last days. The locals aimed to sell everything for Soviet rubles, and to give change in Polish currency. Pretty Polish girls walked in the streets of Novyy Sambor and, with charming smiles, asked Soviet officers to break large Polish banknotes into Soviet money. But there were hardly any fools, even though the suppliants were very charming. One girl simply hanged herself on me, asking me to break a hundred zlotys. I replied that I wasn't rich enough to make her a hundred ruble gift.

Polish banknotes were decorated with portraits of countless Polish kings and queens. Once I heard how our soldier, buying cheap cigarettes from a street vendor, started yelling: "I'm giving you good Soviet money, and you foist (such and such) Polish queen on me as change?!"

I had a complicated relationship with the regiment's chief of staff Captain Severin. He was haughty, demanded that everyone follow regulations to the letter; he didn't like us, reservists. Once I was called on the phone from Staryy Sambor to come to Severin. I reported that to the battery commander, took another soldier with me, we saddled our horses and rode the muddy roads through the rain. We arrived wet outside, sweaty inside. The HQ was located in a former school. It was hot in the large room, kerosene lamps were burning; Severin was pacing the room, dictating something to the clerks, who were writing. Water was pouring off my cap, so I took it off and held it horizontally on my bent left arm. When the captain finally turned to me, I reported my arrival. Severin suddenly fell on me: "Where have you come to? A pub or a land office? How do you behave yourself?" and so on. I stood there without understanding anything. The clerks were giggling behind Severin's back, pointing at me. The captain went on yelling. Everything was coming to a boil in me. Finally, Severin revealed the reason for his wrath: "Why did you, when you entered, remove your cap? What were you trying to say by that? Don't you see that your superiors are wearing their head dress? Why do you report without your cap?!" I couldn't hold it and blurted out: "Just a cultured person's habit, to remove the head dress when entering a room." "Is that so?!" - the captain thundered. "Yes, it's so," - I replied. "About face! Forward march!" - he commanded. I turned around according to all the regulations, clinked with my spurs, and exited onto the porch. I stood there, waited for a rather long time - nothing. Then we tightened saddle-girths and rode back. And so I didn't find out why Severin called me. Possibly, he liked the colorful maps which I drew for our battery and wanted to entrust me with all cartographic work in the regiment's HQ, or maybe, transfer me completely to work in the HQ. Of course, it would've been easier and safer there than in the ranks. But being under a boss like Severin wouldn't have been like chocolate either. This episode didn't pass without consequences. Severin didn't forget our encounter and paid me back any way he could later.

Meanwhile, things in Europe continued heating up. We obviously started being put into a state of battle readiness. Intensified training started, firing of live ammo. I was ordered to lecture the soldiers of the entire battery on patriotism, our duty to defend the Motherland. I didn't have any materials available, I had to talk about Russian history from memory, starting with the Tatar invasion. They said I wasn't bad, although the judges weren't very competent. They started replacing our weapons by more modern ones. But when we were given warm clothes, started making skis for guns, limbers, and caissons, we realized that we were being prepared for action in Finland, where the war had been going by then. But those were only suppositions, because they didn't tell anything even to us, officers.

The things were uneasy on the threshold of the new year, 1940. We, junior officers, decided to celebrate the New Year. We bought a little wine, hors-d'oeuvres. Our politruk found out about that and called us all to him several hours before the New Year for the latest political session. First he told us about the current political events, then he said that the New Year celebration was a bourgeois custom, which did not suit Soviet people, much less Red Army officers. He fed us hot milk with black bread and let us go practically in the morning, when the new year was there for a while.

Winter came, snows fell, and we started getting ready to march. I was put in charge of the signals platoon, telephone and radio operators. There was a lot of equipment, and the men were mostly willful. We re-shoed the horses, changed the oil in guns' recoil systems, loaded equipment onto the carts.

Once, during the latest roll-call of my platoon, I approached a soldier standing in the formation, and pointed out the poor condition of his boots. He quickly bent down, and the bayonet of his rifle, which he held on his shoulder, scratched my forehead and cheek. If I stood at least one-two centimeters closer to the soldier, I could've been left without an eye.

The situation was uneasy and sad not only in our battery. Things were also uneasy around us. Agitation for the creation of collective farms started in the villages. "Purges" began in the cities. Anyone who fit the category of bourgeoisie, store owners, traders, were arrested and deported. But the majority of the Jewish population lived by trade.

In the middle of January 1940 we got an order to march to the nearest railroad station for loading into trains. We formed a marching column. It was a freezing snow covered road. We set out in the morning, we were planning to reach the station by night and start loading. The winter day was short, it became dark early. We were passing through some town. Apparently, there was some local celebration there. Music played in many houses, the windows were lit. One of our mounted soldiers, cold and hungry, looked into an open window from the top of his horse and yelled: "Having a feast, scum, just wait until they come for you." Probably, those were prophetic words.

Sudden misfortune struck me. Two of my radio operators disappeared. I reported that to the battery commander. He grew angry, told me that I should've ridden at the rear of my platoon, not at the front. Then there wouldn't have been any stragglers. He ordered me to ride back and look for them, by myself. I rode my tired horse back, but those stragglers weren't to be found anywhere. I visited the HQ of some unit, but they didn't know anything there. I stopped in some village. The tired horse was thirsty. I gave her water from a pool with a tarpaulin bucket, which I had in my saddle bag. The frost was strong, and it was getting late. I turned back. The horse slipped on a turn, and I, tired and sitting carelessly, flew out of the saddle into the snow. The horse ran on. I got up from the snowdrift, all covered in snow, thinking that I was finished. I had lost my horse. But no, my darling Doll, having run about 10 meters, stopped and started looking back at me. I ran to her, stroked her, pressed my cheek against her neck. Took out some chocolate from a field bag, and we started eating it together. Doll was snorting and taking the treat from my hand with her wet lips. I started leading her along the snow covered road. It was a dark frosty night. I was alone, my strength was leaving me. I saw a solitary, apparently, a "kulak", farm, on a hill off to the side of the deserted forest road. I had no choice. I approached the gate and started knocking. No one replied for a long time. Finally, some voice asked in Polish about what I needed. I said I was a Russian officer and asked them to let me in for the night. The windows lit. Some shadows were walking there. Apparently, they deliberated, consulted on whether they should've let me in or not. Or maybe, let me in and then kill me... Finally, a man with a lantern opened the gate. I led my horse into a warm barn, where cows were mooing, put Doll into a free stall. I barely managed to take the heavy saddle off her, replaced the bridle by a tether, rubbed her with a wisp of straw, poured some oats from the bag for her, put some straw at her legs.

I entered the house. A kerosene lamp with the wick turned down was barely lit. The silent hosts watched me. I said that I needed to rest a little until morning, asked for something to eat. They brought a tin cup of milk and a few boiled potatoes. I ate this modest supper, put three rubles on the table, and again went out to my horse. Now I could water her. Having drunk her fill, Doll laid down on the straw. I wanted to sleep badly, but was there a certainty that I would wake up? There were many cases when Soviets were killed quietly. No one knew that I was here. How easy would it have been for these people, who sooner saw an enemy than a friend in me, to kill me while I was asleep? The horse, the saddle, handguns, field glasses, boots, clothes - all that was valuable, and easy to take. And who would start looking for me? The battery was being loaded and would depart, considering me a straggler. I took my greatcoat and boots off, transferred the equipment to my uniform, and fell flat on the bed, having pushed the handgun in its holster under my stomach. And fell dead asleep. Several hours passed. It started getting a little lighter. I had to go, because I could be late for loading, and where would I go then with my horse? How would I catch up to the train with it?

I dressed, saddled Doll, and set out. The sun rose. Some people were clearing the road from snow. There was the railroad, and the station. But, alas, all was empty. My heart froze. Was I really late and the battery gone? I found the railroad manager and the military commandant. It turned out that my battery hadn't arrived yet and stopped for the night in a neighboring village. The loading only started in the afternoon. And my disappeared radio men came. It turned out that these scoundrels, instead of marching with everyone, decided to get to the station in a truck going the same way. I would've put them under arrest for maybe ten days on bread and water another time. But we were in the middle of loading, and there was not time for that. And so, their base trick went unpunished.

We loaded into "teplushkas" - freight cars with bunks and small iron stoves, every commander with his platoon. When the stoves were stoked, it was hot on top and cold below. Then we set out northward. And so, all doubts disappeared, we were being taken to fight in Finland. The time of year was cold, and the further our train went, the stronger were the frosts. My place was on the second bunk, near a small window whose glass was covered by ice. One night, when I was a sleep, a lock of my hair froze to the ice on the glass. The train moved slowly, which did not make us especially sad. We didn't particularly want to hurry to the meeting with war. I conducted training sessions with soldiers about the communications equipment, lectured on the topics of current politics. At the various stations we were often asked to sell makhorka (very strong and cheap Russian tobacco - trans.) that we were given out. I, as a nonsmoker, usually gave my makhorka to the soldiers. But once, at a station, an old railroad worker approached me wanting to buy makhorka. I had a pack, which I gave to him, but refused to take his money. Then that old man told me, somehow with a heartfelt conviction: "God grant you remain alive." Honestly, I later recalled this wish, because you become superstitious during a war. So when I came out unharmed from dangerous situations, I involuntarily thought that I had bought my life with a pack of makhorka.

Bologoye is halfway between Moscow and Leningrad. We arrived

there in the early morning. The men were still sleeping in the cars. All tracks

were stuffed with trains of military equipment. We came to a stop hear a train

loaded with disassembled aircraft. I was the duty officer, so I had to go to

the military commandant and report our arrival. Looking at the cannons on my

tabs, the commandant thought that a unit of some artillery regiment had arrived,

smiled cordially and told me: "Just arrived? Well, now you'll have to stay

with us for a while. We will put you into a siding now. Give me your papers."

I handed them. Having seen our train number, in which the fateful word "infantry"

was encrypted, the commandant frowned. The smile disappeared from his face and

he said in a different, stern, voice: "Tell the men not to get out of the

cars. We'll send you along immediately." And we rolled on to Leningrad

at once. We suspected that in the woods and swamps of Finland infantry must've

been the main striking force and must've suffered the biggest casualties. That's

why we weren't surprised when we were hurried forward along the main track leading

to the front. Infantry was need there, ahead. Infantry - that was us.

| Translated

by: Oleg Sheremet Photos from the archive of M. Lukinov |

|

|

|

|