"Here is an opportunity to do a big, basic work, such as comes to few in the course of a lifetime. The individual who fails to vision the importance of the task has no moral right to hold a position of authority in its performance."

- Thomas H. MacDonald, Chief, Bureau of Public Roads, December 1921

The federal-aid highway program, which was initiated by the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, got off to a slow start, with only $5 million available the first year. The biggest initial problem, however, occurred in April 1917, when America entered what is now known as World War I. Personnel shortages were compounded by shortages of road-building material and railroad cars to ship materials to project sites.

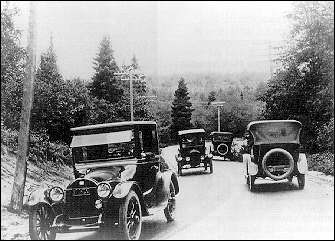

Furthermore, because the railroads were unable to keep up with military shipping, the fledgling trucking industry seized its opportunity to secure interstate shipping. As a result, the roads that the states did not have the resources to improve were deteriorating under the unexpected weight of the loaded trucks.

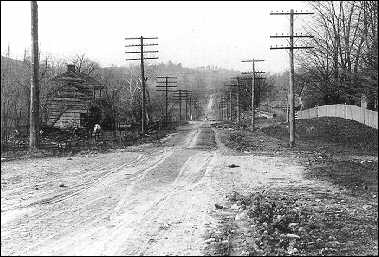

When the war ended in November 1918, the need for changes in the federal-aid highway program became evident. Some features of the program - for example, the definition of "rural post road" and the $10,000 per mile limitation - were a hindrance in many states. The decision to leave project selection in the hands of state highway officials resulted in widely dispersed improvements, spread among political subdivisions and not connected with each other or roads in adjoining states.

Logan Page, director of the Bureau of Public Roads, who was so instrumental in shaping the program, would not have time to address these and other problems with the program. On Dec. 9, 1918, while attending a meeting of the Executive Committee of the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO) in Chicago, Page became ill. He died that night.

Thomas H. MacDonald, who had played a key role in developing AASHO�s federal-aid highway bill, became the new chief in early 1919. With his technical background and his experience as a state highway official, he proved to be the ideal successor to Page in this new phase of highway development.

The most difficult problem facing MacDonald was the gap between advocates of long-distance roads and advocates of farm-to-market roads. The answer developed by MacDonald, in close cooperation with AASHO, was contained in the Federal Highway Act of 1921.

The 1921 act rejected the view of long-distance road advocates who wanted the federal government to build a national highway network. To satisfy them, the act limited federal aid to a system of federal-aid highways, not to exceed 7 percent of all roads in the state. Three-sevenths of this system must consist of roads that are "interstate in character." Up to 60 percent of federal-aid funds could be used on the interstate routes.

By retaining the federal-aid concept, the act also satisfied advocates of farm-to-market roads. The state highway agencies could be counted on to consider local concerns in deciding the mix of projects.

In cooperation with the state highway agencies, the Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) completed designation of the federal-aid system in November 1923. It totaled 272,000 kilometers (km) or 5.9 percent of all public roads. The federal-aid system would expand as states completed work on their original system.

The 1920s were a "golden age" for road building. In 1922 alone, federal-aid projects totaling 16,500 km were completed at a cost of $189 million, three times as much roadway as had been improved since the start of the federal-aid highway program in 1916. The projects usually involved providing graded earth, sand-clay, or gravel surfaces.

In the 1930s, the federal-aid highway program felt the impact of the Great Depression. Federal funds were diverted from projects that served transportation needs to projects that could provide work for the unemployed. At the same time, calls were increasingly heard, in and out of Congress, for transcontinental superhighways - often coupled with calls for toll financing - to accommodate the powerful new automobiles of the day.

The German "Reichsautobahnen" gave American highway officials an object lesson in superhighways after the first section opened in May 1935. Many officials and engineers visited Germany to see the autobahns in operation, and all came away impressed. MacDonald, for example, described the highways as "wonderful examples of the best modern road building." He was, however, less impressed from an economic standpoint. The autobahns were being built well in advance of traffic needs and before Germany was able to realize the likely economic benefits that he thought should justify such projects. Moreover, the autobahns bypassed the cities. MacDonald believed that the primary need for freeways in the United States was in the cities, where traffic jams were an increasing problem.

MacDonald, by this time, had concluded that the time had come for America to begin the next stage of highway development. The federal-aid system would be "completed" by the late 1930s. Although many segments of the rural network had not been paved, virtually all had received initial treatment. As MacDonald said in a 1935 article: �We have reached a point in our development where we can no longer ignore the needs of traffic flowing from the main highways into and through cities and from feeder roads to the main highways.�

To provide the data needed to plan the highway network of the future, MacDonald put his faith in the highway planning surveys conceived by Herbert S. Fairbank, chief of BPR's Division of Information. Fairbank�s goal was a comprehensive state-by-state accounting of traffic on the American highway.

Based on the statewide planning surveys and analysis, BPR prepared Toll Roads and Free Roads. This report became the basis of President Franklin Roosevelt�s master plan in 1939 for a system of interregional highways. This plan laid the groundwork for the future interstate highway system.

References

1. America�s Highways 1776-1976, Federal Highway Administration, Washington, D.C., 1976.

2. Bruce E. Seely. Building the American Highway System: Engineers as Policy Makers, Temple University Press, Philadelphia, Pa., 1987.

Richard F. Weingroff is an information liaison specialist in the Federal Highway Administration�s Office of the Associate Administrator for Program Development.

| Turner-Fairbank Home | FHWA Home | Feedback | Index |

Go to the Public

Roads Website