Throughout the blockade of San Juan, the U.S. Navy attempted to keep at least one cruiser in sight of San Juan harbor entrance at all times. To the people of Puerto Rico, these blockade ships came to be known as fantasmas, or phantoms, appearing at any moment at night or day to capture and, if necessary, sink any vessels attempting to enter or depart San Juan.

The impact of the blockade was soon felt. Puerto Rico's economy was then largely based on sugar production, with extensive importation of basic items, including tools, clothing, and food. Fernando Picó reported "hunger and insatisfaction" due to the blockade. However, the blockade was far from complete (usually a single vessel off San Juan), and the war too short to blame all island shortages on it (1987:46).

Around 1 PM, on 22 June, while San Juan regimental bands played inspiring martial music and a great crowd cheered, ISABEL II an old cruiser and a British built torpedo boat destroyer TERROR left San Juan Harbor to attack the sole blockading American ship, the ST. PAUL. It is possible that the attack may have been an attempt to provoke ST. PAUL into steaming within range of the San Juan shore batteries. The ST. PAUL a large and fast ocean liner made over as an armed auxiliary cruiser with eight 5-inch guns and eight 6-pounders was commanded by Captain Charles D. Sigsbee, previously commander of the MAINE (Nofi 1996:166; Rivero 1972:146, 161; Dyal 1996:287, 322).

As the ISABEL II could only make 10 knots she was soon forced to

retire from the action and return to San Juan for fear of being overhauled

by the ST. PAUL. On its own the TERROR attempted a torpedo attack

to cover the ISABEL II's retreat. The ST. PAUL commenced firing on

the TERROR at 5,400 yards. She was repeatedly hit by small caliber

rounds and 5-inch shells from the ST. PAUL.

The ST. PAUL struck the TERROR’s steering gear, jamming the rudder. As the Spanish ship turned, giving her starboard side to ST. PAUL, the latter fired a 5-inch shell that struck TERROR about 12 inches above the water line, wrecking the starboard engine and killing five men and wounding several others. The shell exited below the water line on the port side, and the TERROR began to sink. Running for port as fast as her other undamaged engine could take her, the ship was in serious danger of capsizing; so her commander beached her on Puntilla shoals [Dyal 1996:287].In San Juan, the bands kept playing, and the crowds began spreading the rumor that the two Spanish vessels had engaged the entire United States fleet offshore (Wilcox 1898:242). The TERROR, which had come up from Martinique on the 17th of June, after being left there by Admiral Cervera on the 14th because of mechanical problems would still be under repair in San Juan when the Spanish Government surrendered in August, and would eventually be the only ship of Admiral Cervera's fleet that would return to Spain.

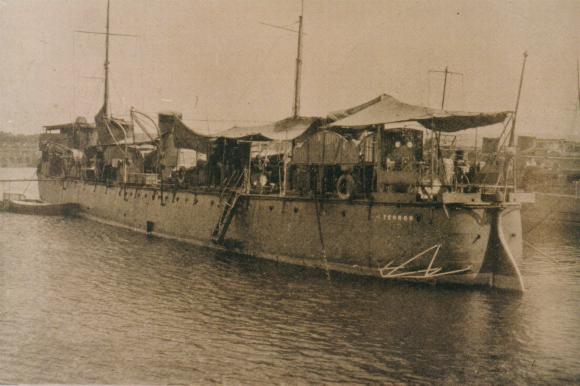

The TERROR in San Juan undergoing repairs after the fight with the ST. PAUL

On 25 June, ST. PAUL was relieved by the

auxiliary cruiser YOSEMITE, soon to become the

hunter of the Trasatlántica blockade runner SS

ANTONIO LOPEZ. Two days later, from Mole St. Nicholas, Haiti,

Sigsbee reported to the Secretary of the Navy:

I decided to come here instead (of proceeding to New York for coaling) in order to recommend to you promptly an increase of the blockading force off San Juan, where the Yosemite now remains alone. I beg to respectfully suggest that the difficulties of blockading the single port of San Juan are greater than those to be met in blockading Havana, where there are no Spanish war vessels and no torpedo--boat destroyers, and where ports are blockaded both to the eastward and westward. . .Sinking a Blockade Runner:

Vessels intending to run the blockade of San Juan can, owing to the short length of Porto Rico east and west, make telegraphic communications with San Juan for advice with reference to the disposition of the blockading force. And this they can do within a few hours of their expected arrival at that port. This can be done by visiting the east and west anchorages of that island or St. Thomas. San Juan being well to windward in the trade region, and having no land influences to windward of it, the seas off that port are naturally continuously rough day and night, making boarding both prolonged and difficult, especially for auxiliary crews . . .. . . blockading a well-fortified fort containing a force of enemy's vessels whose aggregate force is greater than her own, is an especially difficult one.

. . . a considerable force of vessels is needed off that port (of San Juan), enough to detach some occasionally to cruise about the island. West of San Juan the coast, although bold, has outlying dangers, making it easy at present for blockade runners having local pilots to work in close to the port under the land during the night . . .

--Captain C. D. Sigsbee to the Secretary of the Navy, 27 June, USS ST. PAUL (U.S. Navy Department, 1898:220).

By 1898, the Trasatlántica Compania owned 32 liners in addition to the SS ANTONIO LOPEZ, and was the undisputed leader of Spanish shipping interests (Gómez Nuñez 1899:118). Prior to the war of 1898, the Trasatlántica had already played an enormous role in the transport of Spanish troops to-and-from the overseas colonies. Between 1868 and 1886, Trasatlántica steam liners had transported over 250,000 soldiers to the island of Cuba alone.

When the war broke out, some 213,000 soldiers were transported in 15 Trasatlántica voyages. The company's war effort also included hospital ships, contribution of personnel and vessels to the Spanish Navy, and blockade-running expeditions (Casasses and Riera 1987:8).

Blockade runners included vessels from Spain, Cuba, France, Great Britain, Honduras, Norway, Mexico, Germany, and possibly other nations. Most of these vessels were steamers. An extensive listing of blockade runners and Spanish warships captured by the U.S. North Atlantic Fleet was included in the Appendix to the Report of the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation (U.S. Navy Department 1898:316-325). Due to the numerous vessels in the listing, only those directly relevant to Puerto Rico's blockade are discussed.

On 8 May 1898, the Spanish cargo steamer RITA was captured with a coal shipment en route from St. Thomas to San Juan. The capture was made by U.S.S. YALE, Commander N. C. Wise, sending Rita with prize crew to Charleston, South Carolina (U.S. Navy Department, 1898:367). On 9 May, YALE was driven off by an armed transport out of San Juan. This was the auxiliary cruiser ALFONSO XII, an ocean liner armed with 4 Hontoria guns of 12 cm (Gómez Nuñez 1902:75). The maneuver allowed the approaching blockade runner PAULINA to enter San Juan Harbor from St. Thomas (Rivero 1972:72).

On 25 May, ST. PAUL captured the English steamer RESTORMEL, which had left San Juan with 2,400 tons of coal for Cervera's fleet in Santiago de Cuba. Upon questioning by Sigsbee, the British captain responded that there were two other cargo steamers (of the same British company as the RESTORMEL), both loaded with coal, still inside San Juan Harbor.

On 10 June, the British steamer TWICKENHAM, en route from Martinique to Jamaica, was captured near Puerto Rico, possibly its unofficial destination. The capture was made by the ST. LOUIS (U.S. Navy Department 1898:316).

Loss of SS ANTONIO LOPEZ:

SS ANTONIO LOPEZ was the most distinguished of the Puerto Rico blockade runners, not only by her luxurious prewar career, but more importantly, by her secret government cargo for the defense of San Juan, including six breech-loading, bronze cannon of 12 cm; four breech-loading, Mata bronze mortars of 15 cm; two breech-loading, Mata bronze howitzers of 15 cm; also 3,600 projectiles, 500,000 rations, an electric searchlight and fifty tons of gunpowder (Rivero 1972:173).

The arrival of this modern matériel was crucial for the Spanish defense of Puerto Rico. This is reflected in the secret telegram received by Captain Carreras from Don Claudio López Bru (1853- 1925), son of Antonio López and president of the Trasatlántica, "You must deliver the cargo to Puerto Rico, even if it means losing the ship" (Rivero 1972:176).

On 16 June 1898, SS ANTONIO LOPEZ departed from Cádiz with a total of 79 men, including officers, medic, priest, etc. She had no guns above deck, as Captain Carreras had removed her four Hontoria cannon of 12 cm in Cádiz (Vega 1992). She was convoyed as far as Gibraltar by a large part of the Spanish fleet. SS ANTONIO LOPEZ and ALFONSO XII separated there to dash across the Atlantic to deliver government supplies and armaments.

The Transport and blockade-runner, ANTONIO LOPEZ

After eleven days at sea, on the night of 27 June 1898, SS ANTONIO LOPEZ reached the north coast of Puerto Rico. The previous week, on 20 June, the Spanish Governor of Puerto Rico had received a coded cable message of the ship’s arrival date. While El Morro's lighthouse and the city itself were to remain in blackout as a safety measure against possible bombardments at night, the Madrid Government had ordered that the entry buoys to San Juan Harbor be lighted for the nocturnal arrival of SS ANTONIO LOPEZ.

But there were no lighted buoys awaiting the blockade runner on the night of 27 June. Instead, the entrance to San Juan Harbor was invisible. From previous experience, Carreras knew that the waters off San Juan were burdened with deadly reefs. Even in daylight, the narrow channel into the harbor had to be negotiated slowly.

According to Rivero (1972:180), whileSS ANTONIO LOPEZ was lost in the dark, Governor General Macías and General Vallarino drank brandy and played cards at La Fortaleza the official residence of the Governor General of Puerto Rico. When the socializing was over, instead of giving orders to light the buoys, General Vallarino went to sleep.

By dawn of 28 June, SS ANTONIO LOPEZ found itself a few miles off Dorado, well west of the entrance of San Juan. To the east, beyond a morning rain, was San Juan. At that moment, YOSEMITE patrolled off Isla Verde, unable to see SS ANTONIO LOPEZ behind the contoured coast and the heavy rain. YOSEMITE was an unprotected, auxiliary cruiser of 389 ft., armed with four 5-inch guns and six 6-pounders, under Commander William Emory, with a crew largely composed of Michigan Naval Reservists, and university students and graduates (Dyal 1996:358).

The USS YOSEMITE on blockade duty off San Juan

In the light of dawn, YOSEMITE's lookouts noticed the hoisting of signal flags at Fort San Cristóbal. Incredibly, a signal man was announcing the liner's arrival from the west (Rivero 1972:173). Now, with both vessels speeding at full steam towards San Juan, shells from YOSEMITE rained on the ocean liner. Aboard SS ANTONIO LOPEZ, taking hit after hit, Carreras was painfully aware that a good shot could ignite the 50 tons of gunpowder he carried.

Eager to stop the Spanish liner, Commander Emory brought Yosemite well within firing range of Morro Castle and Fort San Cristóbal. But the Spanish guns remained silent. The commanders of both strongholds had explicit orders not to fire until given permission by the high command. With Admiral Cervera's fleet expected anytime, as well as the arrival of blockade runners from neutral nations, fear of firing at their own ships had locked the Spanish forces into an embarrassing inertia.

With YOSEMITE coming closer and always

firing, Carreras followed his last orders: to deliver the cargo in Puerto

Rico, even if it kills the ship. At this point, that could only mean

one thing: to ground the ship on the beach. At first, it seemed like

a good idea, until a loud screech came out of the sea. The ship had

grounded! Suddenly, Carreras had the distinct sensation of wanting

to be elsewhere, anywhere but stuck on a reef with shells raining from

YOSEMITE and enough gunpowder to explode SS

ANTONIO LOPEZ in a million pieces (Vega 1997).

"Abandon ship!" cried Carreras. "Every man for himself!"Boats were lowered into the sea, departing quickly from SS ANTONIO LOPEZ. Undaunted by the distance of over half a mile to shore, some sailors dove into the sea and swam. Carreras himself abandoned the ship, leaving behind his first officer, eight wounded sailors and the ship's priest.

"Abandon ship!" the command echoed in every room [Vega 1992:69].

While YOSEMITE fired at the immobilized liner, out of San Juan Harbor rushed ISABEL II, a 2nd class, unprotected, auxiliary cruiser of 210 ft., followed by the smaller GENERAL CONCHA, variously described as a third-class auxiliary and a gunboat, and the fast gunboat PONCE DE LEON. In San Juan, men, women, and children rushed to the city walls to see the spectacle. Soon the three Spanish vessels opened fire, with YOSEMITE firing back at all three (Vega 1997).

Under heavy fire, shooting its Nordenfelt 75 mm. rifle, PONCE DE LEON sped towards the grounded liner. Circling around SS ANTONIO LOPEZ, the fast gunboat bounced against the liner with such force that the gunboat's mizzen mast dropped like felled timber. Soon the wounded began stepping down into PONCE DE LEON.

At Morro Castle, Commander Iriarte finally received orders to open fire on YOSEMITE. For more than half an hour he had waited for the high command, watching the unprotected American vessel cruise within range of El Morro's big guns. Now, just as the coastal guns were allowed to fire, Yosemite was retreating out of range. Out went the first shell, splashing water about 300 ft. ahead of YOSEMITE. The second shot was already short. Not daring another attack on the grounded liner, YOSEMITE sped towards the horizon.

At 1:30 p.m., the tug IVO BOSCH left San Juan Harbor, followed by the steamboats CARMELITA, CATALINA, and ESPERANZA. For three days and nights the boats unloaded the precious and deadly cargo. Meanwhile, Yosemite watched from a distance, with ISABEL II, GENERAL CONCHA, and PONCE DE LEON guarding the salvage boats.

The operation was commanded by Captain Ramón Acha, a Puerto Rican military engineer later promoted to general in the Spanish army. On the night of 29 June, Acha attempted to free the grounded liner by towing with the auxiliary JUAN MANTILLA. But it was an impossible mission.

Day and night, the salvage continued. Virtually everything was rescued, including the grand piano, the coal, and personal items of the crew. Only a bronze cannon was lost to the sea, when the boat carrying it foundered at night. The following day, the salvors returned with divers and a larger boat, but they were unable to relocate the lost cannon.

By dawn of 15 July, NEW ORLEANS arrived at the scene. A protected cruiser of 354.5 ft., NEW ORLEANS was armed with 23 guns, including ten 50-caliber guns. She had already seen combat at Santiago de Cuba. Exchanging signals with YOSEMITE, NEW ORLEANS closed to three miles of SS ANTONIO LOPEZ. In the morning of 16 July, NEW ORLEANS fired twenty incendiary shells at SS ANTONIO LOPEZ. On the third hit, the liner caught fire, continuing to burn into the following night. Weeks later, the once luxurious Spanish liner disappeared beneath the sea (Vega 1997).

The burned-out hulk of the ANTONIO LOPEZ

Upon reaching Danish St. Thomas, Commander Emory wired a report on SS ANTONIO LOPEZ to the Secretary of the Navy. As told by Mortimer E. Cooley, ex-Chief Engineer of YOSEMITE, to Rivero (1972:188), this was the only U.S. vessel to engage in combat in 1898 and not receive the standard double pay. Years later, Truman H. Newberry, who had served as lieutenant aboard YOSEMITE, became Secretary of the Navy. It was only then, through an Act of Congress, that Sampson's medal was awarded to the men of YOSEMITE for their bravery in detaining SS ANTONIO LOPEZ in enemy waters, without support from other vessels.

Blunders notwithstanding, the secret mission of SS ANTONIO LOPEZZ was a Spanish victory, which may explain the belated recognition of YOSEMITE's crew, and the omission of Spanish salvage operations in diverse official reports and publications (U.S. Department of the Navy 1898 and 1966). The success of the salvage was reported in U.S. newspapers, including New York's Evening Journal of 23 August, doubting the official naval press release regarding the liner's destruction by YOSEMITE (Rivero 1972:185-186).

What is significant about SS ANTONIO LOPEZ as a blockade runner, is the fact that San Juan was empowered by the influx of artillery, projectiles, gunpowder, rations and other cargo salvaged from the stranded liner. After the battle for SS ANTONIO LOPEZ, there were no more attempts to capture or bombard San Juan. Although the U.S Atlantic Fleet had the firepower to destroy the city, now a direct attack would have been costly for both sides (Vega 1997).