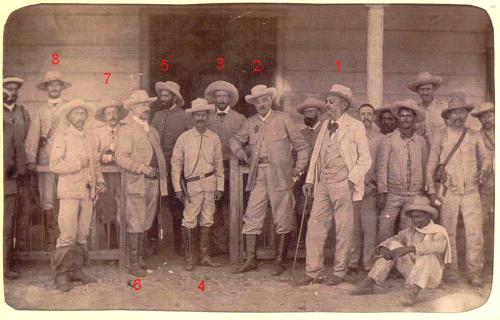

This photograph was taken in Cuba in 1896 at the occasion of the surrender of José Loreto, one of the Chiefs of Cuban Rebel leaders in the Province of Santa Clara. This was during the period when Martínez Campos was Captain General of Cuba. The surrender took place in a Spanish military camp at Las Cendrillas. Those pictured are as follows:

1.- D. Marcos García, Civil Governor of Santa

Clara

2.- General D. Ernesto de Aguirre, Commander in Chief

of 2nd Division

3.- Comandante (Major) D. Silverio Mantilla

4.- D. José Loreto, Chief of Cuban Rebels

5.- Colonel D. Luis Chacón

6.- Captain of artillery D. Luis Massats

7.- Captain of cavalry D. Carlos Escario

8.- Captain of enginners D. Antonio Gómez de

la Torre, Aide-de-Camp of General

Aguirre

(This photography is courtesy of José Gómez

de la Torre, great-grandson of

Captain Antonio Gómez de la Torre, provided

to us by Francisco Jose Diaz Diaz)

The landscape and people of Cuba has not changed greatly since the War of 1895. The island of Cuba lies some ninety miles south of the Florida coast. Its land consists of lush, green jungles and foliage covered hills and mountains. The coast contains beautiful beaches and small disease ridden swamps close-by. The harvested land mostly consists of sugar cane and tobacco fields. In the Nineteenth century, Cuba grew single crop food substitute exports with low elasticity of demand, and vulnerable to extrinsic and intrinsic influences. Cuba became the most important sugar producer after the fall of Haiti; Cuba produced 500,000 tons of sugar, almost a third of the worldís supply, by 1860. The indigenous people that Columbus found in Cuba have long died off since the Spanish settled the island in 1511. By the Nineteenth century, imported African slaves made up a growing segment of the Cuban population, until the complete end of slavery in 1886. The people under Spanish control consisted mostly of darker skin, revealing their African slave ancestry. Others, mostly criollos and peninsulares , have more fair skin, indicating their ties to Europe and colonial power. (Criollos refers to creoles, people born in Cuba of Spanish descent. Peninsulares refers to people born in Spain and they usually controlled the island.)

As with other New World countries, the people of Cuba desired to rid themselves of Spanish colonial rule. Spainís once vast colonial empire and mighty strength shriveled under the sunrise of independence in the early Nineteenth century. Cubaís location in the Gulf of Mexico once provided security of the Spanish territory. Several simultaneous revolts broke out, sparked by the American and French Revolutions, across Latin America. Spain used Cuba as a staging area for its activities, but could not deal with all of these rebellions against colonial rule at the same time. Spain possessed only two colonies in the New World by the end of this revolutionary time, Cuba and Puerto Rico. New nations, freed by their own internecine wars and revolutions, were protected by the [United States implementing the] Monroe Doctrine against further overseas encroachments. The United States feared that if Cuba fell into a European hand, that it would threaten America. This stemmed from the British using the Caribbean as a staging area during the American Revolution and the War of 1812.

The United States has regarded Cuba with want and concern. Thomas Jefferson envisioned Cuba as an American possession. In 1825, Cubaís proximity to the United States caused Secretary of State Henry Clay to state that he feared freed Cuban slaves would come to America and spark slave uprisings. Other politicians viewed Cuba as too weak to maintain any independence from European powers if freed from Spain. Before the Civil War, different segments of the American population saw their own role for Cubaís future. The Northern states wanted the sugar but did not want to admit a slave holding territory, while the Southern states saw Cuba as a leverage against their northern brethren. After the war, the Southern elite did not want the large non-white population admitted to the United States in any capacity that would affect the existing power and social structure. However, the American capitalist saw the exploitative value of Cubaís agriculture, sugar and tobacco, and imperialists saw Cuba fitting into their plans. Secretary of State Richard Olney, under President Cleveland, reassert[ed] the Monroe Doctrine in a diplomatic dispute between England and Venezuela over the boundary of British Guinea in 1895. This pleased the war hawks in the East who wanted to flex American might between Spain and Cuba during this period as well. Spainís actions in handling the several uprisings in Cuba typically raised concerns and territorial ambitions in America. This culminated in the Spanish-American War in 1898, with America stepping between Cuba and Spain after the War of 1895.

Several conflicts between Spain and Cuba preceded the War of 1895. Independence movements in 1825 created the Spanish need to invoke Martial Law in Cuba, restricting the ability to assemble, associate, and operate a press. This set the stage for future uprisings and eventually the War of 1895. The wealthy Cuban elite, criollos and peninsulares, feared the large slave population enough to delay any push for independence by the 1840ís, when forty-five percent of the population consisted of slaves. From 1849 to 1851, a former Spanish General, Narciso Lopez, led Cuban refugees in America on three expeditions of revolution in their native Cuba. The first expedition failed on 11 August 1849 due to intervention of American federal authorities. Southern volunteers joined the second group which landed at Cárdenas and were driven off on 19 May 1850. The third group, including more Americans, left New Orleans and landed near Havana from 11 to 21 August 1851. Lopez failed to incite a revolt from the people. The Spanish captured, tried, and hanged Lopez and fifty-one Americans at Havana. The Cuban people continued to endure the hardship of colonial rule.

A brief interlude without fighting gave way in 1868 when Cuban rebels attacked the Spaniards, the start of the Ten Yearsí War. Carlos Manuel de Céspesdes freed his slaves on 10 October 1868 and began the liberation wave. A Spanish military defector and an intrepid mulatto, Máximo Gómez and Antonio Maceo, respectively, conducted a campaign that failed when their criollos supporters capitulated in 1878 out of fear of the lower classes, skepticism of the strength of the rural worker and the black rebel army. The Cuban insurgents requested help from the United States. They wanted Washington to put pressure on Spain and to use the United States as a staging area, but the United States turned away and remained neutral. The American people, however, felt compassion for the revolutionaries and supported their efforts. A group of Cuban supporters bought VIRGINIUS, a former Confederate blockade runner. A Spanish warship, TORNADO, captured the VIRGINIUS on 1 October 1873 near Morant Bay, Jamaica (to read more about the VIRGINIUS Affair, click here). During the struggle of the Ten Yearsí War, mid-size farms went under to banks and American businesses gobbled up the small ones in an effort to consolidate land holdings. Years of brutality and atrocities, committed by both sides, lasted until 1878, when Spain eventually defeated the rebels. An armistice ended the fighting, yet this did not satisfy the Cuban people who would rise up again in the War of 1895.

The Ten Yearsí War obliterated the sugar industry, dashed hopes for independence, and claimed the lives of 250,000 Cubans. Spain allowed Cuba to send representatives to the Spanish Parliament and greater local autonomy; however, blacks and poor whites could not vote and Spaniards comprised half of the voters. Slavery ended in Cuba in 1886. Researcher Louis A. Pérez wrote: Cuban dependency on the United States grew significantly after the Ten Yearsí War, 1868-1878. A depression in the mid-1880ís led to a few productive system based on corporate latifundia and large centrales. Much credit and investment capital came from the United States. Trade shifted heavily to the United States. The termination of US tariff concessions in 1894 damaged the economy, leading Cuban elites to challenge Spanish economic policy. These developments almost assured that Cuban independence would be followed by Cuban dependency upon the United States.

To a lesser, degree oppression remained initially and new capitalists found their way into Cuba; Pope Leo XIIís 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum, an indictment of early capitalismís exploitation of workers, portrayed the decadence of corporations running unchecked. José Martí, a Cuban exile who led the early efforts of the War of 1895, founded the Partido Revolucionario in 1892 aimed to unify in a single party all those favoring independence. Economically, Cuba aligned closer to America than their Spanish colonial masters as the century entered the last decade. The Panic of 1893 in the United States damaged the Cuban sugar prices. This allowed the American corporations to take over failed farms to secure Cubaís dependency on the United States. Seventy-five percent of Latin Americaís exports to the United States came from Cuba and half of the Latin American imports from the United States went to Cuba in 1894. The United States had well entrenched itself in the Cuban economy and did not want to lose a valuable market so close by. Spain clung to its remaining claim. Cuba was caught in the middle in the mid-1890ís when the United States reduced sugar imports with the Wilson-Gorman tariff and Spain restricted United States imports to Cuba. Proponents of annexation and independence divided Cubaís population. However, the Cubans wanted to rid themselves of Spainís colonial rule and Spainís economic policies. The dam of Spanish rule holding back Cuba started to crumble from the force of Cubaís desires.

The War of 1895, sometimes called the Cuban Insurrection, began in 1895 after Spain suspended constitutional guarantees on 23 February. The next day, independence factions under Máximo Goméz, Antonio Maceo, and exile José Martí started military action near Santiago. Charismatic leaders united this cross cultural, Cuban movement toward a goal of eliminating Spanish control. However, a split developed between the goals of Maceo, who believed in a military faction to control efforts until victory, and Martí, who favored a democratic form. Martí encouraged Maceo and Gómez to conduct military action. Martí aimed for an independence with racial equality, democracy, self-rule, and social justice. He found support among the working-class and middle-class, who donated to the Partido Revolucionario regularly. He realized that the wealthy exiles were too dependent on Spanish control. The war for liberation concerned itself with a social revolt to dislodge the planter class and to fight for colonial independence. Martí died in a skirmish on 19 May 1895 with Spanish Colonel Ximénez de Sandoval, after which, the insurrection began to go badly. Many historians believe that if Martí survived the war Cuba's history would be completely different. Martí, who wrote extensively, exhibited repugnance for America and malice towards capitalism, as evident in his unfinished letter to Manuel Mercado: It is my duty . . . to prevent, through the independence of Cuba, the U.S.A. from spreading over the West Indies and falling with added weight upon other lands of Our America. All I have done up to now and shall do hereafter is to that end. . . . I know the monster because I have lived in its lair - and my weapon is the slingshot of David.

One Cuban junta even helped start and feed the rebellion while operating in the United States, and the American people supported Cuban insurrectionists, especially after tighter control answered the rebellion. By June 1895, the six or eight thousand rebels faced fifty-two thousand Spanish soldiers and nineteen warships. The rebels operated mostly in the elevated countrysides of eastern Cuba. The Spanish, without mobility to bring needed reinforcements, stayed on the roads and in towns to avoid the rebelís wrath. After the start of the War of 1895, Spanish Captain General Martínez Campos, who commanded and controlled the island for the Spanish empire, wrote in June: We are gambling with the destiny of Spain. . . . The insurrection today is more serious and more powerful than early 1876. The leaders know more and their manor of waging war is different from what it was then. . . . Even if we win in the field and suppress the rebels, since the country wishes to have neither an amnesty for our enemies nor an extermination of them, my loyal and sincere opinion is that, with reforms or without reforms, before twelve years we shall have another war.

He clearly understood the situation and foresaw fighting until Spain lost its hold on Cuba. Spanish Captain General Valeriano Weyler arrived in January 1896, replacing General Martínez Campos as governor and Commander-in-Chief. He possessed Machivellian qualities and quickly institutionalized concentration camps for noncombatants, where thousands would perish (though this was probably not his intention). On 21 October 1896, he issued the reconcentration order, stating: I order and command all the inhabitants of the country now outside of the line of fortification of the towns, shall, within the period of eight days, concentrate themselves in the town so occupied by the troops. Any individual who after the expiration of this period is found in the uninhabited parts will be considered a rebel and tried as such.

Cubans, mostly women and children, lived in famine and disease. This act alienated more American opinion. Furthermore, the American press sent reporters to Cuba, where the Journal and World published incendiary stories, and when the truth paled they invented atrocities to incite more public opinion. President McKinley told Spain in July 1897 to halt Weyler or the United States would intervene. When Spainís premier died in August 1897, a liberal government came in, which pulled Weyler and gave Cuba more autonomy by October 1897. General Rámon Blanco, more tolerant, replaced General Weyler and quickly ordered a reversal of the harsh policies by giving out aid and reorganizing rural industry.

At the political level, the War of 1895 consisted of the Spanish government in Spain and Cuba and the leaders of the Cuban independence movement. Each side established their own political objectives to define victory. Spain controlled only Cuba and Puerto Rico in Latin America as the Nineteenth Century came to a close and the Spanish crown did not want to lose Cuba. The brutal Spanish Captain General Valeriano Weylerís, known as devoid of political understanding, created domestic and international discord during his reign over Cuba. The Cuban independence movement sought freedom from its colonial master and faced political problems and legitimacy from a lack international recognition. Early on they desired a democracy during and at the end of the War of 1895, especially Martí, but the Spanish-American War derailed the effort.

At a strategic level, a power identifies security objectives and allocates the resources required for its accomplishment. Additionally, the power establishes risk limits and initiates plans to secure the political objective. A Spanish designated commander-in-chief acted with fairly free hand in Cuba. The Spaniards accepted the risk of international reprisals and condemnation. Spanish forces operated with far greater numbers of soldiers than the Cubans. The Cubans suffered limited manpower and equipment. Ideological differences, such as the one between Martí and Maceo, hindered the assignment of strategic objectives by the Cubans. Unable to achieve a set political goals, both the Cubans and Spaniards failed strategically in the War of 1895. This allowed the United States to enter Cuba in 1898.

On the operational level, a nation designs and sustains campaigns, moves its forces, and aims at the enemyís culminating point to achieve the strategic objectives. Operational objectives link strategy and tactics. Spanish forces moved on main roads and through towns on foot, avoiding the countryside. They established concentration camps to remove any possible guerrilla support in the countryside. By doing this, the Spanish could not attack the Cubanís center of gravity, the rebel forces themselves. The Cubans operated in the rural parts, hiding in the hills and forest. They predominately received logistical support from other sympathetic Cubans. The rebels also received smuggled arms from Florida and funds from New York. The Cubans guerrilla campaign style permitted them to move over distances without interference, but they did not threaten Spanish control of cities. The sedentary tactics of the Spanish never took the fight directly to the rebels to link it to their strategic objectives. The Americans would take the fight to the Spaniards in the next war. It was no wonder the Spaniards expected the United States annex Cuba. Jefferson had included it as part of his dream of expansion; John Quincy Adams considered it indispensable to the continuance and the integrity of the Union; the South coveted it; Polk tried to purchase it; and the Ostend Manifesto prepared to steal it.

The tactical level involves the actual soldiers and combat. The fighting accomplishes the military objectives through planning and execution. The Spanish leaders and soldiers received training, but acted without any professionalism. The Spanish operated with nearly 200,000 men. Their tactic of relying on heavy regiments instead of mobile forces, such as cavalry units, to sweep the countryside proved to be faux pas. As the fighting increased early on, the defensive minded Weyler instructed his forces to construct strong point block houses and erect barbed wire to section off the land. He intended to isolate the guerrilla forces operating in the country side. The Rebel and Spanish forces both [resorted] to scorched-earth tactics.

The Cubans functioned as a guerrilla force. They fought in small numbers, ambushed the enemy at opportune times, and used an irregular cavalry force at times. They probed the Spanish defenses for weak areas to hit. The rebels came down from the rugged mountains and scoured the countryside for Spanish soldiers and sympathizers. The rebels took what little was available from the local farmers. They extorted American companies and burned sugar cane fields as well. Facing a force five times its size, the liberation army pushed the enemy steadily until 1898 [when] Spain and its commanders were exhausted militarily and economically. With the Cubans on the brink of triumph, the United States snatched victory.

In the War of 1895, Cuba had lost one sixth of its population from combat and disease. The War of 1895 washed away many of Spainís reservoirs of assets and drive. Loyalists in Havana had rioted against home rule on 12 January 1898, and the United States consulís request for protection resulted in the battleship USS MAINE being sent to Cuba. Writer Philip Brenner wrote: The Cubans had nearly won the war by February when the United States battleship Maine - in Havana harbor to protect U.S. property and to signal the Cuban rebels that the United States was worried about the course the revolution would take - exploded.

When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, Cuban rebels achieved little success because the United States Army employed them as labor troops. This signaled the role that Cuba would endure under American control for the decades to come.

The United States viewed Cuba in the Nineteenth century as an island to economically exploit and a country needing American control. Spain shored up its last New World possessions to contain their last Latin American independence surge. Spanish colonial policies and conflicts, several insurgencies and Ten Yearís War, culminated in the War of 1895 for independence. The War of 1895 resulted in near victory for the Cubans because of Spanish inability to achieve their political, strategic, operational, and tactical objectives. The United States jumped in with its own agenda, which began a half century of direct American influence over Cuba. After the long, bitter fighting in the Nineteenth century, Cubans secured a moderately better life, but lost their dream of freedom.

Dupuy, R. Ernest and Trevor N. Dupuy, The Encyclopedia of Military History from 3500 B.C. to the Present, 2d ev. ed. New York: Harper & Row, 1986.

Gunn, Gillian, Cuba in Transition: Options for U.S. Policy, New York: Twentieth Century Fund, 1993.

Handelman, Howard, The Challenge of Third World Development, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pentice Hall, 1996.

Hatchwell, Emily and Simon Calder, In Focus Cuba: A Guide to the People, Politics and Culture, London: Latin America Bureau, 1995.

Hawthorne, Julian, United States, Vol. 3, From the Landing of Columbus to the signing of the Peace Protocol with Spain, New York: Peter Fenelon Collier, 1898.

Lande, Nathaniel, Dispatches from the Front: News Accounts of American Wars, 1776-1991, New York: Henry Holt & Company, 1995.

Manchester, William, Controversy: And Other Essays in Journalism 1950-1975, Boston: Little, Brown, & Company, 1976.

Musicant, Ivan, The Banana Wars: A History of United States Military Intervention in Latin America from the Spanish-American War to the Invasion of Panama, New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1990.

Olcott, Charles S., The Life of William McKinley, Vol. 4, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1916.

Pérez, Louis A., Jr., The Collapse of the Cuban Planter Class, 1868-1968, Inter-American Economic Affairs 36, no. 3 (1982), Historical Abstracts [CD-ROM], print entry no. 35A:8086.

Pérez, Louis A., Jr., Toward Dependency and Revolution: The Political Economy of Cuba Between Wars, 1878-1895, Latin American Research Review 18, no. 1 (1983), Historical Abstracts [CD-ROM], print entry no. 35A:4542.

Skidmore, Thomas E. and Peter H. Smith, Modern Latin America, 4 ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Thomas, Hugh, Cuba: The Pursuit of Freedom, New York: Harper & Row, 1971.