Henry Alexander Schimberg Goes to War

2nd Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry,

Co. G.,

(As told by his younger

brother, Albert Paul Schimberg)

Contributed by Carin Rhoden

Click here to read about the

history of the 2nd Wisconsin

Click here to read about

the 2nd Wisconsin on a forced march!

Click here to read

about the 2nd Wisconsin's departure for Puerto Rico!

Click here for the

roster of the 2nd Wisconsin

Click here for

information on the Battle of Coamo

Relatives of Mr. Schimberg can email Carin Rhoden by clicking

here!

General:

This is the account of Albert Paul Schimberg describing how his brother,

Henry Alexander Schimberg went off to war with the 2nd Wisconsin Volunteer

Infantry, Co. G.

The Acount:

From "Quiet Rebel" by Albert Paul Schimberg:

When one evening in April, soon after this country

declared war on Spain, the Appleton Crescent printed a list of the

soldiers who had left that day for war service, my brother's [Henry A.

Schimberg] name was missing. The next morning I marched into the

Crescent

office and told them so. That evening's paper contained a little

note giving Henry's name and other names "inadvertently" omitted from the

earlier list. I continued to be as patriotic as the dickens and intensely

proud of my soldier brother, but my ardor was dampened a little when, one

evening, I happened to go upstairs and there slumped against a window-sill

I saw my mother crying her heart out. This was something I had not

reckoned with, had not expected. This was something about war that

I didn't like at all. But I kept on being proud of my soldier brother,

Henry, who had enlisted in Co. G, the Appleton unit of the Wisconsin National

Guard. It was from him that letters came to 877 Lake Street from Camp Chickamauga,

Ga., and later from Puerto Rico. Those from

the Philippines came from a cousin of my mother's,

Eugene Pierrelee. Because Henry was with the troops invading island, we

were of course more interested in the Puerto Rican than in any of the other

campaigns of the war. Even before the Wisconsin troops were landed

on the island, while they were still in camp, in this as in all wars rumors

circulated in the Ward and throughout the city, as doubtless in all other

towns of the whole country. A martinet regular army general, fat

on a horse, compelled the raw volunteers to march interminable miles under

a blazing Southern sun. In camps, nothing was done to prevent flies

from visiting the outdoor eating places after having visited the camp latrines.

The summer uniforms so sorely needed by the troops did not reach them,

they were forced to wear heavy uniforms throughout the summer in tropical

latitudes. A persistent vaudville joke even sometime after the war

ended was this: "In the Middle Ages armor saved the lives of soldiers.

In this war (Armour food) killed soldiers." Some of the stay-at-homes

of military age, or older, called the whole affair a comic opera war. It

was a contest between the American giant and a diminuative Spain, and there

was such ineptitude, such bragging, such an avid desire for publicity as

had their comical aspects. But no war, no matter how brief, how unequal

the strength of the contestants, is a comic opera affair. It was

a serious matter for the soldiers who fought and bled, and died, and for

their loved ones. The rumormongers did not even spare the mothers

and fathers of the soldiers. A rumor that Henry had died in Puerto

Rico reached his mother's, his father's, his sweetheart's ears. Their agony

of waiting, of uncertainty was not relieved by catchwords, bombastic speeches,

the reports of glorious victories by Richard Harding Davis and the other

bright young men to whom the war was a romantically interesting adventure.

In our case, the rumor proved false. In many cases, reports of death

in battle or from disease were all too true. Before victory finally sat

on our standards.

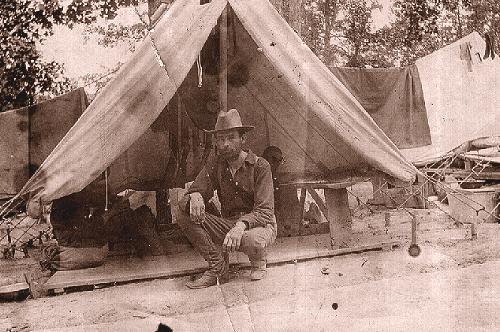

Henry Alexander Schimberg in camp

We followed the news of the Wisconsin regiment to

which Henry belonged. We did not know, then, how on one occasion, after

having been landed on Puerto Rico, the Americans were marched through a

valley between hills, from which, had they been alert, the Spaniards could

have directed a deadly fire on their enemies below. Nor did we know,

then, what havoc disease wrought among our troops and that Henry fell sick

with a tropical disease just as his regiment was about to embark for home

at the war's end. The sick, those who could not walk, were to be

left behind, to the mercy of inadequate sanitary personnel and provisions.

Then it was that my brother's knowledge of French served him well.

Determined not to be left behind, to a fate at best uncertain, he managed

to get a ride in a carriage with a number of officers, though he was no

more than a corporal. En route to the coast, where a ship was waiting,

the Americans were overtaken by nightfall and lost. After some time

they saw a light in the distance and came upon a plantation owner's home.

But the planter was not at all friendly; did not seem inclined to offer

hospitality to the tired, sick Americanos. Something in the man's speech

told Henry that he was French, or at least spoke with a French accent.

So my brother addressed him in the French language, and at once the man

grew friendly. He took the officers and corporal into his house,

dined them, opened bottles of splendid wine, and the next morning directed

them to the port and the waiting ship.

On the Sunday in September, 1898, on which the Appleton

soldiers were to be welcomed home, the Zouaves of St. Joseph's parish were

summoned to Mass, after which they would march to the railway station to

greet the returning heroes. Well, the sermon at that Mass was longer

than even the usual lengthy sermon at St. Joseph's. On and on droned

the preacher, while we Zouaves, especially those who had older brothers

in the army, fidgeted and wished he would finally bring his discourse to

a close. When we were finally released from church, it was too late.

No proud marching to the station for us. We were dismissed and each

ran to catch up with his soldier brother by this time nearing home.

I caught up to Henry on Brewery Hill, a few blocks from home. It has always

seemed to me that someone ought to have told the preacher that among his

supposed-to-be hearers were the parents and brothers and sisters, and

sweethearts of the soldiers. This once the sermon might have

been cut short, or omitted entirely, to give the excited people an opportunity

to be at the railway station when the troop train pulled in.

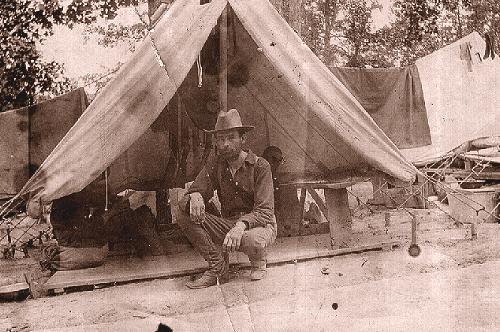

An image believed to be of Mary Schimberg, Henry's

sister, wearing his uniform and hamming it up for the camera. This version

was hand colored by computer by Carin Rhoden.

To visit the website bibliography, click

here. To visit the website video bibliography, click

here

.