A Philadelphia Story

by

Adam Levine

Historical Consultant

Philadelphia Water Department

Contents Copyright � 2002 by Adam Levine

All Rights Reserved

Permission must be received to reprint any of the following material in any form

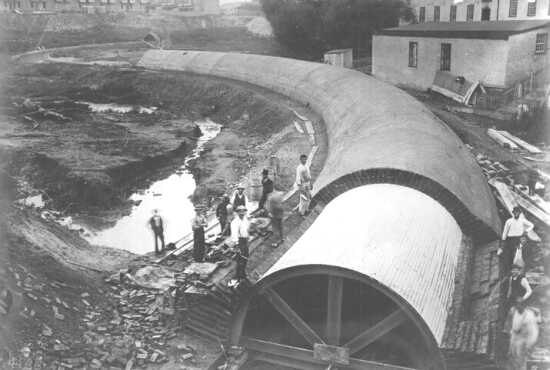

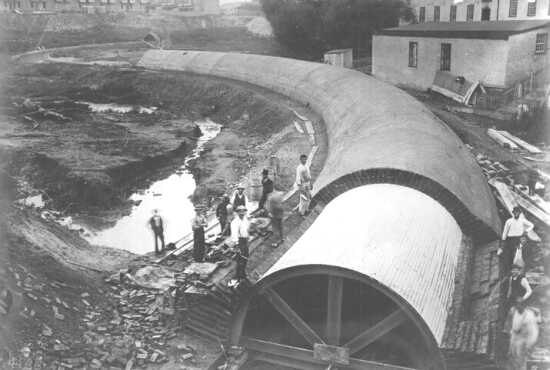

Mill Creek Sewer under construction, 1883

Mill Creek Sewer under construction, 1883

(SOURCE: Phila. Water Dept.)

“There have been great changes in the face of [Philadelphia], in its levels and contour, and in the direction and beds of its water-courses since the days of the Swedes and the early Quakers. Some streams have disappeared, some have changed their direction, nearly all have been reduced in volume and depth by the natural silt, the annual washing down of hills, by the demands of industry for water-power, the construction of mill-dams and mill-races and bridges, the emptying of manufacturing refuse from factories, saw-pits, and tan-yards, and by the grading and sewerage necessary in the building of a great city. In this process, old landmarks and ancient contours are not respected, the picturesque yields to utility, and the face of nature is transformed to meeting the exigencies of uniform grades, levels and drainage. The Board of Health, the Police Department, the City Commissioners, and the Department of Highways have no bowels of compassion for the antiquarian and the poet. They are the slaves of order, of hygiene, of transportation, of progress.” (SOURCE: J. Thomas Scharf and Thompson Westcott, History of Philadelphia 1609-1884. Philadelphia: L.H. Everts & Co., 1884, Vol. I, p. 5-6)

Unlike the 1884 history of Philadelphia cited above, many histories of human settlement often overlook the alterations in the landscape that made possible the patterns of settlement in a particular area. Partly this is because changes in topography and hydrology are usually hidden beneath the development that follows them, and therefore difficult to discern and document. Little evidence of obliterated landscape features exist in tangible form, unless one counts the infrastructure of sewers that underlies most cities and is accessible to only a select group of municipal employees.

As in many urban areas, most of Philadelphia's surface streams, encompassing many square miles of watershed, were systematically obliterated over the course of the city's development. Diverted into pipes--their valleys leveled with millions of yards of fill and overlaid with a grid of streets--these streams now flow in some of the largest sewers in the city's 3,000-mile drainage system. In most cases, these projects were designed as combined sewers, carrying raw sewage along with the stream flow and stormwater runoff. For this reason alone, it would be prohibitively expensive to “daylight” such streams, since it would mean building a completely separate system of pipes to carry the sewage.

1914 plan of Philadelphia's sewers, showing the former Mill Creek

1914 plan of Philadelphia's sewers, showing the former Mill Creek

(SOURCE: Adam Levine)

As appalling as this wholesale destruction of the natural landscape might be to those with post-Earth Day environmental sensibilities, use of urban streams for sewage disposal--and, ultimately, as the beds of actual sewers--was standard practice for 19th and 20th century engineers. Initially, stream pollution and its deleterious affect on health was the main reason for undertaking such drastic measures. When a section of the Cohocksink Creek in Philadelphia was “culverted” in 1860, the Board of Health applauded the project as “one of the most valuable sanitary improvements ever to be undertaken by the corporate authorities.... For years this natural tributary of the Delaware...has been a prolific source of miasma. The entire length of its serpentine bed had become the receptacle of vile refuse and dead animals, while its sides were lined with privies, emptying their contents upon its filthy surface; added to these, the offal from cow-stables, dye houses, slaughter-houses, kitchens, and the impurities from various trades and factories, together with street-sewage--the whole forming a hotbed for the conversion of its contents, when exposed by the receding of the tide, and acted upon by heat and humidity, into poisonous gases,--thus predisposing to and causing the spread of low types and malignant forms of disease throughout the entire vicinity. The sanitary value of the change effected by the culverting of this creek is above price. Its influence upon the health of the population of the entire surroundings, it is impossible to define. Our bills of mortality for that district, will, no doubt, hereafter furnish an approximate answer.”

Wingohocking Creek Sewer under construction, 1909

Wingohocking Creek Sewer under construction, 1909

(SOURCE: City Archives of Phila.)

By the second half of the 19th century, as epidemic diseases such as typhoid fever killed thousands of Philadelphians, providing proper sewerage and drainage became a subject of great concern, and city engineers began planning the culverting of creeks in advance of development. As early as 1853, City Surveyor Samuel H. Kneass acknowledged that natural watersheds would have to be utilized to provide proper drainage for the city. In the 1880s, when the City engineers drew up their preliminary drainage maps for Philadelphia's 129 square miles, converting many of the city's smaller streams into sewers was an integral part of the plan.

By doing this work in advance of development, the engineers hoped to solve several problems. Since it was standard sewage disposal practice to direct branch sewers downhill into the nearest stream, they knew that even pristine surface streams would become polluted once the areas around them were developed. Culverting the streams before they became polluted was seen as a positive step to protect the public health. In undertaking these projects, the engineers also hoped to reduce the cost of the city's infrastructure in a number of ways. Sewage, being mostly liquid, flows most cheaply by gravity--pumping it up a slope is expensive in terms of fuel costs, and is only as reliable as the pumping equipment. By placing sewers in the natural stream valleys, the engineers got the gravity flow they needed, and in the process they managed to avoid the high cost of making extensive excavations. Once the valleys were filled in over the newly built pipes--in some stream valleys in Philadelphia, more than 40 feet of fill was used--the cost of building a bridge each time a main street crossed the stream was avoided as well.

1910 plan showing Torresdale Avenue overlaid on Little Tacony Creek

1910 plan showing Torresdale Avenue overlaid on Little Tacony Creek

(SOURCE: Phila. Water Dept.)

Building sewers in advance of development also gave engineers more freedom in their designs. Since most of the land the sewers traversed was open farmland or woodland, the cost of paying out land damages to property owners was less. Often, building a sewer in a creek bed was to the advantage of private landholders, especially in areas of the city where the rectangular grid system of streets prevailed. A piece of land with a creek cutting through it was impossible to subdivide into regular slices, but with the creek in a sewer, and the grid laid over the valley, real estate speculators could divide their property into the tightly fitted rectangular lots so common throughout Philadelphia. Since the streets were built on top of the new sewers, with water and gas lines put in as well, the developers had a ready-made infrastructure that tended to speed up the sales of these lots. The City, in return, could count on a quick return on its investment in infrastructure from the resulting increase in tax revenues from the new buildings.

In some watersheds, it took many years to completely obliterate the main stream and its tributaries. The Mill Creek conversion from creek to sewer took more than 25 years, and the city's largest such project, the burying of both branches of Wingohocking Creek, took about 40 years. Early in the 20th century, city planners realized the benefits of creating parks in stream valleys, but it was too late for most. The modern map of the city's surface streams is now disturbingly blank.

Aramingo Canal during its conversion into a sewer, April 1, 1901

Aramingo Canal during its conversion into a sewer, April 1, 1901

(SOURCE: Phila. Water Dept.)

RETURN TO HOME PAGE