The Gun - Smoothbore Era 1550-1860: ProjectilesAs the arrow was the principal projectile in use prior to the advent of the gun, so it continued to be used with early 14th century ordnance which were of light calibre.

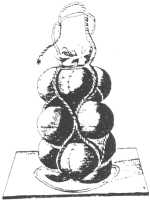

Known as 'darts', 'quarrels', 'carreaux', 'garros', etc, gun arrows were short, with heavy oak shafts, iron points or 'heads' and metal 'wings' in place of feathers. Wings were mounted on three or four sides to ensure the projectile was centred in the bore and stabilised in flight, while the shaft was wrapped with leather to assist in centring and at the same time to provide a gas-tight fit. Round ShotGun arrows were expensive to make and soon gave way to lead balls. The latter, being made slightly oversize in calibre to ensure a gas-tight fit, had to be forced into the bore, for which purpose each gun was supplied with a 'drivell' (drift) and a hammer. Of course this method of loading was suitable only for the small-calibre breech-loading bombards then in use. Neither gun arrows nor lead shot were suitable for the larger pieces which began to appear during the last quarter of the 14th century. It was still possible to use lead - with windage - but lead was expensive. Gunmakers thus turned to other materials. History records that the Italians, then a step ahead of other nations in the development of artillery, used small quantities of bronze and iron shot early in the second half of the 14th century. However, use of these materials appears to have been short-lived, probably because bronze was expensive and the iron shot - probably of wrought iron - were expensive also. By 1364 the Italians, closely followed by other countries, were using stone shot. Stone was plentiful as well as cheap. In addition the spate of church building then taking place ensured there were always stone masons ready to turn their skills to the conversion of blocks of stone to spherical shot. The projectiles thus formed were called 'gun stones', a term which survived for some years after stone was superseded by cast iron! Although cheap stone had its disadvantages. The shaping of shot by hand was a slow process. It was light compared to iron; to be effective a shot had to be heavy, and to be heavy it necessarily had to be large, hence the 'think big' bombards. Furthermore, stone shot fired at a solid target often broke up on impact without causing appreciable damage. Something better was needed. As the technique of casting iron in Europe developed during the 15th century, so iron roundshot began to supersede gun stones. Italy was using cast iron shot during the early 1400s, closely followed by Germany. When England commenced is not clear, but records show she was producing large quantities of iron roundshot by 1512. But stone shot died hard; one English authority mentions its use as late as 1578. Cast iron roundshot was to be the chief projectile for the whole of the smooth-bore era, ie to the middle of the 19th century. Hot ShotGunners soon found that the ideal projectiles for the destruction of wooden targets, eg ships, buildings, etc, were cast iron roundshot heated to redness. Loading, of course, had to be smartly carried out, and to prevent the hot shot from igniting the propellant charge, a wad of turf was inserted in front of it. Stephen Batory, King of Poland, is credited with having pioneered the use of red-hot shot in 1579. Note that the Royal Navy usually avoided the destruction of enemy ships by sinking or setting on fire, preferring to capture them, put prize crews aboard, bring them back to England, and there sell them. The prize money was distributed among the crew, of which the Captain got the lion's share, other Officers the bulk of the remainder, while the ordinary seaman got enough to get drunk on. Grape was the preferred weapon; it cut through rigging and killed the crew, thus putting the enemy ship out of action without damaging it too much. Grape ShotGrape was so-called because in its original form a round resembled a bunch of grapes. Termed 'quilted grape', it comprised a number of heavy iron balls. A later form was 'tier grape'. The balls in each type, known as 'sand shot' varied in weight from a few ounces up to 4 lbs (1.8 kg) each, according to the calibre of the gun. Grape was never fired from bronze guns as it damaged the bores, nor was it used in the field. Grape was superseded by case toward the end of the smooth-bore era. Its maximum effective range was 600 yards (549 m). | |||||||||

Quilted Grape |

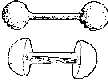

Tier Grape | ||||||||

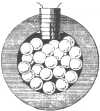

Case ShotThe ancient forerunner to case was 'langridge', a quantity of junk such as bits of scrap metal, old nails etc, even gravel, loaded loose into the gun and used against troops in the open. Then Gunners put the junk into containers and called it 'canister' or 'case'. Further improvement followed; the container or case of sheet iron or tin in cylindrical form was filled with cast iron balls each varying in weight from 2 ounces (57 grams) to 8 ounces (227 grams) for the smaller guns, and from 8 ounces to a pound for the heavier. Case was fired from all natures of ordnance against troops in the open, at ships' rigging and boats, effective range being about 350 yards (320 m). On being fired the metal canister burst open at the muzzle, the contents producing a shotgun effect. Case proper was first used at the siege of Constantinople in 1453 and was still being used in World War 2, eg in the American QF 37-mm anti-tank gun. In the latter projectile the canister was filled with lead balls of about 12-mm diameter set in rosin and was said to be effective against troops in the jungle warfare of the Pacific Islands. Carcass

Bar, Chain and Expanding ShotThere were innumerable examples of these projectiles. All were designed to damage ships' rigging, small boats or any unfortunate sailor who happened to get in the way. They date from the 17th century. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

Common ShellThese were merely hollow cast iron spheres filled with gunpowder and fitted with a time fuze. They were fired from mortars and howitzers only until the introduction of shell guns during the 19th century. Shell have been with us almost as long as shot, the earliest reference to their use being by the Italians in 1376. Early time fuzes were simply pieces of quickmatch cut to length by questimation, inserted into a hole in the shell, and ignited by a linstock or portefire thrust down the barrel of the piece. The howitzer was then fired quickly - the Gunner in the meantime praying to St Barbara that it would not backfire! Both mortar and howitzer barrels were very short in the early days. It is said that at the siege of Limerick in 1639 a Gunner accidentally discovered that the flash of the propellant charge would ignite the fuze by way of the windage allowed in those days. He had forgotten to light the fuze before firing his mortar! The invention of the watch in 1674 made more precise fuzes possible. We shall examine their development later in this paper. Shrapnel

Despite its success the original projectile suffered prematures caused by ignition of the burster brought about by friction with the balls. In 1849 Colonel EM Boxer RA put the The field guns in use during the decade preceding World War 1 fired only shrapnel. However, its failure to deal effectively with barbed wire entanglements, its high cost of production, plus the time taken to train officers how to employ it, led in 1915 to the introduction of high explosive (HE) for QF 13 and 18-prs. Shrapnel was officially declared obsolete in the British service in 1935, but continued to be used in obsolete ordnance, eg 18-prs Mk 1 and 2 still in use in New Zealand until 1941.

WL Ruffell, 1996

previous | index | next | |||||||||

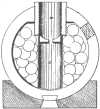

Centuries before the coming of the gun, incendiary missiles fired with Greek fire or similar compositions were hurled at enemy buildings by mechanical engines. Incendiary missiles designed to be fired from guns were termed 'carcasses'. The early carcass was oval in shape. Inside the frame of metal bands was a container of canvas, paper or other suitable material into which was poured a molten mixture of gunpowder, saltpetre and tallow which was allowed to harden. In order that the flash from the propellant charge would easily ignite the filling, the walls of the container were pierced with two or three holes into which priming composition and quickmatch were inserted. Later carcasses were made spherical and in the 19th century were hollow cast iron spheres. Carcasses were fired from mortars and howitzers only. The image on the right is an early form of carcass frame.

Centuries before the coming of the gun, incendiary missiles fired with Greek fire or similar compositions were hurled at enemy buildings by mechanical engines. Incendiary missiles designed to be fired from guns were termed 'carcasses'. The early carcass was oval in shape. Inside the frame of metal bands was a container of canvas, paper or other suitable material into which was poured a molten mixture of gunpowder, saltpetre and tallow which was allowed to harden. In order that the flash from the propellant charge would easily ignite the filling, the walls of the container were pierced with two or three holes into which priming composition and quickmatch were inserted. Later carcasses were made spherical and in the 19th century were hollow cast iron spheres. Carcasses were fired from mortars and howitzers only. The image on the right is an early form of carcass frame.

The term 'shrapnel' was often wrongly used during and after World War 2 to describe shell splinters or fragments. In all shrapnel projectiles lead balls were the killers. Case shot was very effective against troops in the open, but only up to about 300 metres. A weapon to produce a similar effect at greater ranges was therefore highly desirable. To this end in 1784 Lieutenant Henry Shrapnel RA (1761-1842) invented what he called 'spherical case', the original version of which was a common shell with a filling of musket balls and powder. Note that the bursting charge was sufficient merely to break open the shell; the musket balls relied for their killing power solely on the velocity imparted to them by the remaining velocity of the shell at the point of burst. Probably because he was only a Lieutenant when he invented spherical case, the authorities did not deem it worthy of development. However, in 1803, by which time he had risen to the rank of Major, they were prepared to put it into production. Shrapnel proved quite successful during the Napoleonic wars; the French had no answer to it. In 1814 Shrapnel was given a pension of 1200 pounds a year for life for his service to the Crown.

The term 'shrapnel' was often wrongly used during and after World War 2 to describe shell splinters or fragments. In all shrapnel projectiles lead balls were the killers. Case shot was very effective against troops in the open, but only up to about 300 metres. A weapon to produce a similar effect at greater ranges was therefore highly desirable. To this end in 1784 Lieutenant Henry Shrapnel RA (1761-1842) invented what he called 'spherical case', the original version of which was a common shell with a filling of musket balls and powder. Note that the bursting charge was sufficient merely to break open the shell; the musket balls relied for their killing power solely on the velocity imparted to them by the remaining velocity of the shell at the point of burst. Probably because he was only a Lieutenant when he invented spherical case, the authorities did not deem it worthy of development. However, in 1803, by which time he had risen to the rank of Major, they were prepared to put it into production. Shrapnel proved quite successful during the Napoleonic wars; the French had no answer to it. In 1814 Shrapnel was given a pension of 1200 pounds a year for life for his service to the Crown.

burster in a separate metal container while at the same time fitting a wooden bottom to the shell to protect the fuze. In a second modification in 1853 he separated balls and bursting charge by a diaphragm, a principle employed in later cylindrical projectiles. In 1852, ten years after Shrapnel's death, his family petitioned the Government to have spherical case re-designated 'shrapnel', and were successful.

burster in a separate metal container while at the same time fitting a wooden bottom to the shell to protect the fuze. In a second modification in 1853 he separated balls and bursting charge by a diaphragm, a principle employed in later cylindrical projectiles. In 1852, ten years after Shrapnel's death, his family petitioned the Government to have spherical case re-designated 'shrapnel', and were successful.