|

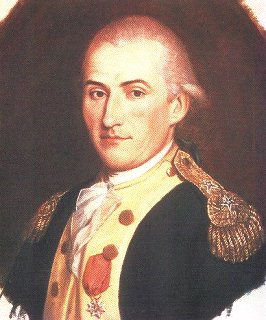

Louis Le Bègue de Presle du Duportail was born in Pithiviers in 1743. His father was a lawyer in the king's service. In 1762, Louis entered engineering school in Mézières as a lieutenant. He rose quickly to the rank of engineer in 1765, and captain in 1773.

What brought him to America?

In September 1775, Foreign Minister Vergennes gave the young secret agent, Julien Achard de Bonvouloir, the mission to sound out the newly formed government of the insurgent American colonies. De Bonvouloir met secretly with Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia and advised Vergennes that Congress would like to have "two skilled and well-recommended military engineers." That request would increase to four engineers in 1776 when Franklin arrived in Paris to represent the insurgent colonies.

The French War Minister, the Count de Saint Germain, contacted Duportail, promoted him to the rank of lieutenant-colonel and gave him leave in February 1777 to "attend to his personal affairs". In fact, his secret mission was to put together the team of military engineers requested by Congress. Wary of spies in Franklin's entourage (only 60 years later was it discovered that Franklin's secretary, Bancroft, was a British spy), Duportail gave Franklin only the background of his men, without identifying them.

Difficult Beginnings

The four engineers — Duportail, des Hays de la Radière, Laumoy, Gouvion (Gouvion Saint Cyr's cousin) — set sail from Nantes on March 5, 1777 using their noms de guerre. When they arrived at Cap Français in Saint-Domingue, they found no boats to take them to the American coast. Fortunately, a colorful character named Monsieur Carabas, who was working with Beaumarchais, found them a boat that took them to New River, North Carolina. Governor Casswell then provided them with horses and carriages to take them to Philadelphia where they presented themselves to Congress on July 5th.

When one follows these men as well as other French volunteers who had arrived in a rather disorderly fashion, one is surprised by Congress' meddling attitude and the wrangling and squabbling that these men had to endure. George Washington, was unable to obtain from Congress either the commissions promised to the military engineers or the reimbursement of their expenses for the trip to America. Duportail estimated that he paid 17,000 pounds out of his own pocket in five years, double the amount that Congress had offered to pay him.

Silas Deane, sent to Paris by Congress, encouraged young Frenchmen to volunteer for service in America and promised them high ranks for their services. One of these young men, Troncon du Coudray, presented himself to Congress on June 2nd. — even before the arrival of Duportail — and said that Deane had promised him the rank of Artillery Commander. Du Coudray's unexpected death on September 16 1777 did not resolve the problem. Astride his horse on a boat crossing the Schuylkill River, he drowned when his horse jumped into the water.1

Then it was LaFayette's turn to arrive in Philadelphia with 11 more volunteers. He, too, was surprised not to receive his commission from a Congress that was split into factions — many of its members still favored the English. An angry LaFayette wrote to Washington, whom he thought of as his father: "I thought that all these good Americans were united and that you had the unlimited trust of Congress. Put aside your great modesty for a moment — excuse me, dear General, if I take the liberty to say this to you — and you would see that if you were not here for America, no one would maintain the army and the revolution would be lost in six months. The dissension that exists in Congress is well-known: the factions that divide it detest each other as much as they detest their common enemy. Men without military experience try to judge you and make ridiculous comparisons. They are infatuated with Gates and think that it is enough to attack in order to be victorious ...... I must give credit to General Duportail and to the other French officers who have spoken with me, for being as worthy as I could hope for on this occasion." 2

In this difficult environment, Duportail fought five campaigns in America.

First Campaign (1777-1778)

Duportail joined Washington at Coryells Ferry. Given the rank of colonel, then brigadier general, he took command of the American Sapper Regiment. He also played an important role as advisor to George Washington for overall planning of the war.

It was Washington's custom to call meetings with the some ten generals under his command. Among them were several Europeans in addition to Duportail: the Marquis de LaFayette, Baron de Kalb, and Baron de Steuben. He asked each one to draft a written memorandum before the meeting. Many of these notes have been saved and bear witness to Duportail's military competence and sound war strategy — as well as his progress in English.

When Duportail joined Washington, the War for Independence was at its lowest ebb. No money for the troops, many deserters, the terrible winter at Valley Forge — and the English had occupied Philadelphia, the young Nation's capital.

The memorandum that Duportail sent to Washington at that time certainly represents a turning point in the war. He opposed the position of many of the American officers. Brave but inexperienced, they proposed to attack Philadelphia to liberate the capital. In a ten page report, Duportail demonstrated that it would be strategically better to remain near Philadelphia — even to retreat slightly. Brilliantly, he showed that the English could not remain at Philadelphia because their defenses were too weak. 3

In fact, that is exactly what happened. On June 18, 1778, the English evacuated the capital. They had also just learned that France had recognized the independence of the American colonies. Allied with the insurgents, France was sending a fleet and troops to America!

The English marched north towards New York. Washington pursued them. On June 28, he engaged the English at Monmouth, New Jersey. When the patriot troops were in full retreat under General Lee, Washington rode into battle and saved the day. The English pulled back to New York and Washington continued north to White Plains.

Washington then sent Duportail to a liberated Philadelphia with the mission to fortify the city while Congress went back to work. Duportail's mission was extremely important as Philadelphia was an easy target for the English navy.

Second Campaign: a fort on the Hudson River (1778-1779)

Late in 1777, Congress had ordered Washington to supervise the construction of a fort to control the Hudson River in order to prevent the English, who controlled New York, from cutting off American troops in New England from those south of New York. Washington sent LaRadière, under orders to General Putnam — a brave soldier, who, unfortunately, knew little about how to build a fort.

While everyone was talking about fortifying West Point, the conscientious La Radière wrote a report demonstrating that the best site for the fort was at Fort Clinton, and not at West Point. He added, however, that he would follow orders. The American generals as well as the governor of New York all disagreed with LaRadière. The fort would be built at West Point.

After several indecisive attempts to change commanding officers, Washington finally dispatched Duportail to inspect both forts. His report in September 1778, outlined all the improvements to be made on these forts and confirmed that LaRadiere had been right in the first place.4

By this time, the French officers were becoming discouraged and were thinking about returning to France as their two-year leave was about to end. It took all Washington's authority and the encouragement of Conrad-Alexandre Gérard (France's first ambassador to the United States who had signed the Treaty of Friendship) to convince Congress to ask King Louis XVI to prolong his officers' leave.

In his letter to Congress in November 1778, Washington spoke highly of these men: "Concerning General Duportail, it is only just to observe that I have a high opinion of his merit and his competence. I judge him to be, not only highly qualified in his specialty, but also a man of sound judgment and great knowledge in the art of war. I also have a very good opinion of his companions. I take the liberty to add that, in my opinion, they will be very helpful to us for our future campaigns whether they be defensive or offensive….." 5

Third Campaign: 1779

In March 1779, a Congressional decree created the Military Engineering Corps. Duportail was named its Commander-in-Chief. Washington then sent Duportail with a message to Congress in Philadelphia, asking that the fortification of the Delaware River estuary be undertaken immediately. After enduring much haggling between the Congressional Military Commission and the Governor of Pennsylvania, Duportail was finally given the means to accomplish his task — thanks, once again, to the intervention of General Washington. However, other duties called, and he had to leave the project in the hands of Genton, Chevalier de Villefranche.

The British were on the move again, and Duportail was called back to West Point where he commanded 5,000 men. In July 1779, the patriot troops had charged the fort at Stony Point on the Hudson, captured the British stocks of arms and munitions and destroyed the fort. However, the British returned and rebuilt the fort as well as the one at Verplank's Point. The patriots planned to re-take the forts.

Duportail's memorandum, dated July 27 1779, prepared for General Washington, was truly a masterpiece of military planning. Refusing to let his emotions get the better of common sense, he advised the Americans not to attack Stony and Verplank Points, thus weakening their position at West Point. He further demonstrated that the topography made it too dangerous to bring munitions and artillery into the two forts, and that the enemy could not hold their positions very long.6 Two months later, the British left the two forts without a fight. Once again, Duportail had been right!

Fourth Campaign: Duportail is taken prisonner (1780)

The year 1780 began once again with a terrible winter for the American army. There was nothing for them to eat. The soldiers' contracts expired and many just left for home. Morale was very low.

To make matters worse, the British had already begun to make inroads in the South. Late in 1779, Admiral d'Estaing's fleet had come to help the American cause, but suffered a disastrous defeat in Savannah. The British General Clinton was on his way to take Charleston, S.C. when Washington sent Duportail to help General Lincoln defend the city.7 Washington wrote, from his Morristown headquarters, to Lincoln on 30 March 1780 as follows:

"Dr. Sir: This will be delivered to you by Brigadier General Du Portail, Chief Engineer; a Gentleman of whose abilities and merit I have the highest opinion and who, if he arrives in time will be of essential utility to you. The delay that will probably attend General Clinton's operations in consequence of the losses he has suffered on the voyage, makes me hope, his assistance will not come too late; and the critical situation of your affairs induces me to part with him, though in case of any active operations here I should sensibly feel the want of him. From the experience I have had of this Gentleman, I recommend him to your particular confidence. You will find him able in the branch he professes; of a clear and comprehensive judgment; of extensive military science, and of great zeal assiduity and bravery; in short I am persuaded you will find him a most valuable acquisition and will avail yourself effectually of his services. You cannot employ him too much on every important occasion.

"Every appearance indicates that the enemy will make a most vigorous effort to the Southward. My intelligence from New York announces a further embarkation. The moment it is ascertained I shall advise you of it, and of the corps that compose the detachment.

"I am with the warmest wishes for your success and with the truest esteem etc."8 [Bold font added by webpage editor.]

Duportail arrived in Charleston on April 25, 1780. Crossing enemy lines by night, he managed to reach General Lincoln in the beleaguered city. The situation was desperate, and Duportail proposed to evacuate. The American commander, concerned about possible British reprisals upon the city's citizens, elected to surrender. Duportail was taken prisoner but managed to send messages to Washington and La Luzerne, who had replaced Gérard as French ambassador. He could be released but only in exchange with a British officer of the same rank.

Duportail suffered through the summer heat in Charleston, its polluted water, and swarms of mosquitoes. Finally, he was released in an exchange of prisoners on November 7. His companions, Laumoy, Cambray, and L'Enfant were to remain captives until the end of the war.

Fifth Campaign: Towards Victory at Yorktown (1781)

In July of that same year, 1780, Chevalier de Terney's fleet arrived at Newport, R.I. with Rochambeau and some 4,000 soldiers. The people of Newport were, at first, wary of Rochambeau's men quartered in the town, but Rochambeau soon won their admiration as he was determined not to be a burden on the population. Even the young ladies in the town were charmed by the gallantry of the French officers who represented some of the finest noble families of France. President Stiles of Yale University overcame the language barrier while dining with Rochambeau by conversing in Latin!

Soon after Duportail's release in Charleston, Washington dispatched him to meet with Rochambeau in Newport. Duportail remained with Rochambeau three weeks to discuss war strategy. The French military Engineer's professional assessment of the conditions in America and his personal knowledge of capabilities – and weaknesses – in the American forces were extremely valuable to Rochambeau, who found Duportail to be an equally trusted staff officer as did Washington. Duportail accompanied Washington and Rochambeau to their meeting in Wethersfield, Connecticut, in May 1781. Wisely, it was decided that any attack on the British position in New York would be disastrous without the help of a naval fleet. Early in June, Rochambeau set out with his troops to join Washington's army on the Hudson River. In August, a message arrived announcing the arrival of the French fleet commanded by Admiral de Grasse who favored engaging the British in Chesapeake Bay. Reluctantly giving up his project of capturing New York, Washington recognized the wisdom of de Grasse and Rochambeau. After successfully feigning an attack on New York, Washington set out for Virginia with some 2000 soldiers, accompanied by Rochambeau's 4,000 troops in late August.

Washington sent his trusted Duportail galloping on ahead to Cape Henry at the mouth of the Chesapeake. There he boarded the Ville de Paris to confer with de Grasse and present to the French naval commander Washington's dispatch of 17 August which provided the Supreme Commander's critical assesment of the allied options in the Southern Theater. Washington's dispatch was personally carried south by Duportail and hand delivered to the admiral on 2 September. Washington's dispatch expressed his change of strategic direction from New York to the south, and gave his assessment of options as to specific courses of actions the allied commanders might have to decide.

" We are not sufficiently acquainted with the position of Charles town, neither is it necessary at this time, to enter into a detail of the proper mode of attacking it, or of the probability which we should have of succeeding. For these will refer your Excellency to Brigadier Genl. du Portail Commander of the Corps of Engineers in the service of the United States, who will have the honor of presenting this. That Gentleman having been in Charles town as principal Engineer during the greater part of the siege, and in the Environs of it as a prisoner of War a considerable time afterwards, had opportunity of making very full observations, which he judiciously improved.

" A variety of cases different from those we have stated may occur. It is for this reason that we have thought proper to send General du Portail to your Excellency. He is fully acquainted with every circumstance of our Affairs in this quarter, and we recommend him to your Excellency as an Officer upon whose Abilities and in whose integrity you may place the fullest confidence.9 [Bold font added by webpage editor.]

Duportail convinced de Grasse to wait until all the troops had arrived by land before engaging the siege of Yorktown. Duportail wrote to Washington: "I think that we have no choice. When there are 27 French ships of the line in the Chesapeake, and when the French and American forces come together, we must take Cornwallis. Otherwise, we will suffer dishonor."

Rochambeau's and Washington's troops gathered at Williamsburg where they found LaFayette and his men as well as 3000 men under St. Simon who had disembarked from the French fleet. DeGrasse, after defeating the British fleet in the battle of the Capes, then blocked the entrance to the Chesapeake, to prevent help from reaching Cornwallis trapped in Yorktown. The combined French and American forces with Duportail commanding the Corps of Engineers then besieged the Yorktown and forced Cornwallis to surrender.

On October 19th, General O'Hara, representing Cornwallis, rode out to present his sword to Rochambeau. Rochambeau gestured to Washington astride his horse and simply said: "Our Commander-in-Chief, Sir, is General Washington."

"At this moment what had only been a confrontation between two colonial powers in a foreign land became the birth of a new nation."10

After the War of Independence

On November 16, 1781, Congress promoted Duportail to the rank of Major General in the American Army, and gave him a six-month leave from duty. Upon his return to France, he was made Chevalier de Saint-Louis and promoted to the rank of Brigadier on June 13, 1783.

Back again in America, he organized the Army Corps of Engineers. His detailed training program included an officer training school with a three-year program including courses in chemistry and war-planning. He also organized how each unit of the corps would be set up in various regions of the country. Finally, he gave the corps its motto, which it has kept for more than 200 years: "Essayons".

Epilogue

Upon his return to France, Duportail held different posts, including that of instructor for the royal army in Naples.

During the French Revolution, he was named Minister of War from November 1790 to December 1791. Considered as a 'suspect', he was obliged to hide and fled to America where he lived on a farm near Philadelphia. In 1801, Bonaparte called him back to France. Sadly, he died at sea and was buried in the Atlantic Ocean.

Some viewers of this page might note that the year of DuPortail death has been changed [corrected to '1801' from '1802' that was posted in 2005]. The incorrect year of his death appears to be stated in all known current biographical summaries about him. This correction is due to interestingly new detail covering DuPortail's death uncovered by the research of Serge Le Pottier, retired colonel in the Engineer branch of the French Army and former French liaison officer to the US Military Academy at West Point. Colonel Le Pottier has found in the French archives evidence that Duportail embarked from New York Harbor on a small American ship, Sophie to go to France. The morning 11 August 1801, the ship's captain, Isaac Handconstate, recorded that one of the passengers – known to have been a former French Minister of the War -- died during the night of 10/11 August. An inventory -- now in the French archives -- of DuPortail's effects was made by four French witnesses. However, before the Sophie reached its French port, it was intercepted by an English frigate Tartare and escorted to England. The French passengers eventually reached France, where the four witnesses reported DuPortail death to the mayor of Le Havre on 8 septembre 1801. Unfortunately the report contained an error in DuPortail's name which was not cleared by his heirs until 1840. We must await further clarification in a new biography of DuPortail to be published by Colonel La Pottier.

One cannot help but wish that a talented movie producer, either in France or in the United States, could bring Duportail's story to life as one of the unsung heroes of Franco-American friendship!

|

|

Notes

1. Responding to the request for military engineers by the Congress, Silas Deane had dispatched, with discrete assent of the French Government, Du Coudray in November 1776, before Franklin's arrival in Paris. Du Coudray had traveled on a Beaumarchais ship (as was the case of most volunteers from France, including Steuben). Du Courdray's departure was briefly delayed due to French authorities superficially acquiescing to British protests of such French support to the American rebels. The French military engineer managed to set sail all the same. [See on French Volunteers webpage.]

2. Lafayette's 30 December 1777 letter to Washington is indirectly referenced in The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745-1799 Edited by John C. Fitzpatrick (1931-44) Preface to the Electronic Edition [volume 10 under http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/washington/fitzpatrick/ ], wherein Washington's 31 December 1777 reply is ammended as follows:

[Note: This letter, dated Dec. 30, 1777, is not now found in the Washington Papers. Sparks, however, prints it in vol. 5, P-488, of his Writings of Washington. From this the following is an extract: "When I was in Europe, I thought that here almost every man was a lover of liberty, and would rather die free than live a slave. You can conceive my astonishment when I saw, that Toryism was as apparently professed as Whigism itself. There are open dissensions in Congress; parties who hate one another as much as the common enemy; men who, without knowing any thing about war, undertake to judge you, and to make ridiculous comparisons. They are infatuated with Gates, without thinking of the difference of circumstances, and believe that attacking is the only thing necessary to conquer. These ideas are entertained by some jealous men, and perhaps secret friends of the British government, who want to push you, in a moment of ill humor, to some rash enterprise upon the lines, or against a much stronger army."]

3. Duportail's advises Washington not to attack Philadelphia in two memoranda: first in 25 November 1777 and again in 3 Dec 1777. See pp.178-179, and pp.182-183 in Paul K. Walker's Engineers of Independence: A Documentary History of the Army Engineers in the American Revolution, 1775-1783.

4. Duportail 13 September 1778 report on the fortification at West Point. See pp.216-219 Paul K. Walker's Engineers of Independence: A Documentary History of the Army Engineers in the American Revolution, 1775-1783.

5. Washington's 16 November 1778 letter to Congress spoke highly of French Engineers – especially Duportail: See: "To THE PRESIDENT OF CONGRESS from Head Quarters, Fredericksburgh, November 16, 1778." in Electronic Edition "Original Manuscript Sources – The Writings of George Washington 1745-1799" Edited by John C. Fitzpatrick (1931-44): volume 13 under http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/washington/fitzpatrick/ .

6. Duportail's 27 July 1779 memorandum advising Washington not to attack Stony and Verplank Points. See pp.226-228 in Paul K. Walker's Engineers of Independence: A Documentary History of the Army Engineers in the American Revolution, 1775-1783.

7. Clinton sailed from New York in December 1779 with 8,500 troops to join some British forces at Savannah. The object was to seize Charleston, the prize city in the South still held by the American Rebels. Though delayed by winter storms, the British expedition landed on Simmon's Island in mid February 1780. Clinton then moved to establish his position on James Island, to the south and west of Charleston. Marching upon Charleston via James Island, Clinton cut off the city from relief, and began a siege on 11 April. The British quickly closed all land escape routes from the city. Bowing to pressure from the civilian population in the city, fearing damage to their property should the British take the town by assault, Lincoln offered, on 21 April, to abandon Charleston, but with his army intact. This offer was refused, as was a 31 April offer to surrender his army with full ‘honors of war'. Eventually, Lincoln was forced to surrender his American army on 12 May 1780. The British denial of the American to surrender with "full honors" at Charleston was remembered when the situation was reversed at Yorktown in 1781

8. This text taken from the Electronic Edition of "Original Manuscript Sources – The Writings of George Washington 1745-1799" Edited by John C. Fitzpatrick (1931-44): volume 18, under http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/washington/fitzpatrick/ . Note: The draft is in the writing of Alexander Hamilton. The date line is in the writing of Washington. The draft is indorsed by Tilghman as of March 28.

9. Washington's critical assessment of the strategic situation as conveyed to the French naval commander is presented at: http://www.xenophongroup.com/issues/17-aug.htm Only a small part of this dispatch is reported here. Source: pp.108-109, Thayer's Yorktown: Campaign of Strategic Options: taken from Fitzpatrick, ed., Writings of George Washington, vol.23, pp.6-11. Note: Washington prepared this dispatch at his Phillipsburg (NY) camp and gave it to Duprotail to hand carry to Virginia.

10. Quoted from President Francois Mitterand's speech, commemorating the bicentennial of the victory at Yorktown, on October 19, 1981.

|

|

This basic article was prepared by Daniel Jouve who is an author and an amateur historian with a particular interested in the French and American Alliance during the American War For Independence. He finds, that the leaders were intelligent and honest on both sides of the Atlantic. M, Jouve is a graduate of Lycée Louis le Grand, like LaFayette; a graduate of Harvard, like John Adams. He has written a book with his wife, Alice, a graduate of Boston Latin School, like Franklin: Paris, Birthplace of the U.S.A., a walking guide for the American Patriot (1995).

|

|

Little notice is given to the sculpture composition – one of four – surrounding the base of ‘Lafayette's monument' in the park across from the White House in Washington DC. Depicted the on the west side of the monument are the Comte de Rochambeau and the Chevalier du Portail, two French army officers whose professional military talents contributed immensely to the winning of American Independence. The image should alert us to a particular crucial role Duportail had in cementing the professional cooperation between Washington and Rochambeau, neither of whom spoke the other's language and who had very different military backgrounds.

Little notice is given to the sculpture composition – one of four – surrounding the base of ‘Lafayette's monument' in the park across from the White House in Washington DC. Depicted the on the west side of the monument are the Comte de Rochambeau and the Chevalier du Portail, two French army officers whose professional military talents contributed immensely to the winning of American Independence. The image should alert us to a particular crucial role Duportail had in cementing the professional cooperation between Washington and Rochambeau, neither of whom spoke the other's language and who had very different military backgrounds.