- 'With the Cavalry'

- from the book : The Marne and After

- by Major A. Corbett-Smith 1917

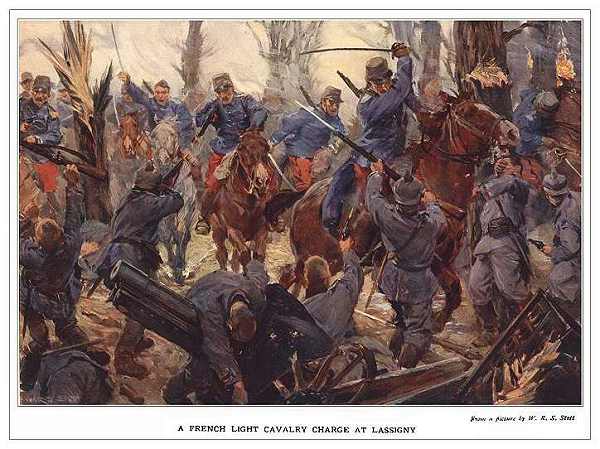

a Cavalry Charge in the old Tradition

a colorful illustration of a French cavalry charge

WITH THE CAVALRY

PICTURE to yourselves our own fair county of Kent; enlarge the picture as you would a photograph, and you will see a little of this fragrant countryside of France through which our men are now advancing.

A land rich in orchards, where heavy branches dip down to lazy streams and tell a double harvest of their glowing fruit. A land of yellowing corn, through which, like wind- tracks, run the straight, poplar-lined roads, rising and bending to the gentle hills. A land of tiny towns and sleepy hamlets, of noble chateaux glimmering white against the sky, of tiled cottages and thatched barns dimly seen against the blue dusk of the woodlands.

Into this fair land have the Huns carried their fire and rapine. But thus far and no farther. Along the banks of the little river of the Grand Morin ran the line of their southern most bivouacs that eve of the Allied advance.

And ever in touch with them our own cavalry patrols are now beginning to drive them back. De Lisle is out there with his 9th Lancers, 4th Dragoon Guards and 18th Hussars. Hubert Gough, too, with the 3rd and 5th Cavalry Brigades.

That first day there was comparatively little fighting, at least on any big scale. The French were pushing ahead pretty fast and seemed to be doing most of the work. With us it was more an affair of outposts, in which the cavalry were more particularly engaged. Little disputes over the passage of a stream, the clearing of a cluster of barns, a squadron charge upon a spitting machine-gun, and so on.

Typical of this fighting was a trifling affair near Pezarches. A squadron of Lancers was working in advance of a section of Horse Gunners when their scouts were suddenly fired upon from behind a hedgerow which ran across some farm buildings. Two of ours were hit, one in the arm, one in the leg. The four advance scouts, who were dismounted, at once began to fall back upon the main body, firing as they retired.

In the meantime the C.O. dismounted half his troop and lined a parallel hedge to pour in a hot return fire. The other half-troop worked round under cover of a wood to try to get the enemy on the flank. The enemy fire seemed to slacken, and some of the Germans were seen making for their horses.

"They're bolting! Come on, boys," and the subaltern was in his saddle and over the low hedge with his men after him in less time than it takes to tell.

But half way across the open a couple of machine-guns opened fire straight in front. The subaltern mixed up a curse with a prayer that the other half-troop would get round in time and held straight ahead.

Over the next hedge and the subaltern launched straight into the middle of a litter of astonished pigs. Down came the horse and two piglets had all the breath knocked out of them. It was rather inglorious, but they certainly saved the officer's life. Before he could get up his half-troop were in amongst the few remaining enemy troopers, while the machine-guns went on spitting death into friend and foe alike

Now the Gunner subaltern had grasped what was happening, and it looked rather serious; nor could lie see how he was to lend a hand. Anyway, he decided to trek after the second half-troop. Round the wood the section went at a canter just as the troop was clear and lining up to charge. And then Lancers and Gunners in those breathless seconds could tell what they were up against.

It was a regular little tactical trick of the Germans. A handful of cavalry would form a screen, and working up behind would come a couple, say, of fast motor lorries, each carrying 40 odd men, Jaegers generally, and a couple of machine-guns. The cavalry would hold the line while the infantry deployed, and would then slip away, unmasking the machine-guns. But in this case the enemy evidently had not noticed our flanking movement.

You have to make up your mind pretty quickly in a case like that, and the guns swept out into the open without a check of the pace. A sudden wheel. Then, "Halt, action front! and an admirably placed shell informed the Huns that the game was not to be so one-sided after all. Before six rounds had been fired two of the machine-guns were out of action and the Lancers charged, while the gunners turned their attention to the motor lorries. One lorry got away; the other didn't. And a quarter of an hour later one of the first batches of Huns was on its way to comfortable quarters in England.

The whole affair had lasted about a quarter of an hour, and the dear old lady who owned the farm looked on all the while from an upper window, as though it were a stage play arranged for her especial benefit. When it was all over down she came to help with the wounded and dispense drinks.

The subaltern who had jumped on the pigs, an4 was none the worse for the adventure save for a sprained ankle, tried to explain.

“Mille pardons, madame," said he in his best French, "trees fache' j'ai jumped on votre petits porcs."

That settled it. Madame didn't know what he meant, but she recognised "porcs" and flew out into the yard.

"Good heavens," exclaimed the Gunner subaltern who was helping to carry one of his men into the house, "there's some cursed German after the women." And he drew his revolver and ran, too, as shriek after shriek rent the air.

Round the corner he came full tilt upon half a dozen Lancers doubled up with laughter round an old woman who was calling heaven to witness her grievous loss.

"What the -" he began, taking a trooper by the scruff of the neck. And then he saw.

Well, quiet was at length restored and Madame eventually pacified by a golden half- sovereign and the first subaltern's cap badge. And that gallant officer is, I am glad to say, still ready and willing to heave you out of the window whenever you may innocently inquire as to the price of pork. But as he is now a major you have to be rather discreet.

The Germans had certainly brought their machine-gun work to a fine art. In the earlier volume I have described how they used them in infantry attack, and a few more notes at this stage may also prove of interest.

The great importance which the enemy attached to machine-guns is seen from the fact that where the British Army went in for rifle practice and competitions like those at Bisley and elsewhere the Germans held machine-gun competitions. They consider these to be in-finitely more valuable. Each infantry regiment carries with it perhaps twelve of these guns, and they are always moved as a part of the regimental transport.

And the ingenuity which has been expended upon this transport is as remarkable as anything in their military organisation. Secrecy seems to be the dominant note. They are carried either on light motor-lorries or two-wheeled carts; sometimes on stretchers with a rug or covering thrown over. And at a short distance away these last look for all the world like a wounded man being carried by a couple of Red Cross orderlies. In fact, on many occasions our men have been completely taken in by the trick and have held their fire.

The carts, too, are generally provided with double bottoms, in which the machine-guns are packed, and perhaps four men ride in the vehicle. The rest of the cart is piled up with odds and ends of various kinds, and no one would guess the real contents. Instances have been recorded at G.H.Q. where some of these carts were captured and the guns never discovered until later someone knocked a bottom through by accident.

Then they have another trick of burying a machine-gun when there is a risk of capture. A wooden cross is put over the "grave," and, of course, no one would dream of disturbing the "body."

But as we have long since come to expect from the Huns, several of the transport tricks are not legitimate. Cases of abuse of the Red Cross were quite common. Knowing the enemy now for what they are it is obvious that they would not miss so excellent an opportunity of getting up close to their opponents by emblazoning their machine-gun lorries with a big red cross.1 One can recall several instances where our men or French or Belgians have allowed a German Red Cross ambulance to drive close by when, as it passed, the hood (of steel) has been slipped down to disclose a machine-gun which has promptly opened fire.

One particularly flagrant case was recorded a week after the Advance had begun. Here a party of Germans was seen advancing and waving a Red Cross flag in front of four stretchers carried by orderlies. The British officer ordered the cease fire and the party approached. When they were about 800 yards off a murderous maxim fire was opened. A general mix-up followed, and after our reinforcements had satisfactorily disposed of the would-be murderers the stretchers were found with the machine-guns still strapped on them.

As our advance pushed on, although it was rather a slow business at the outset, the fighting became more severe. The enemy made the best use of the difficult country, and we were continually checked by their cavalry and machine-gun tactics. When it was a question of dealing with their cavalry alone, and our own had half a chance, it was all over in a few minutes. It was the combination which worked the mischief. But even here the balance was not too heavy against us, for our cavalry seemed to be as useful dismounted as they were mounted, while their shooting was well up to the standard of the infantry.

I cannot do better than illustrate these two sides of our cavalry work by two incidents which, oddly enough, happened in the same engagement.

A regiment of German Dragoons had pushed its way south through the little village of Moncel after the retreating British. Now had come the inexplicable order to abandon the pursuit and return the way they had come. It was not in the best of tempers that the dragoons clattered once again down the village street, for the cursed English cavalry had been leading them a rare dance all the afternoon, and the experience had not been a pleasant one.

Captain Schniff with a squadron will hold the village till further orders," the colonel commanded as he took the remainder of the regiment with him on the northern road.

The captain did not feel too happy about the position, and thought once or twice of telephoning to headquarters for a couple of maxims. However; deciding to make the best of it; he turned his attention to instilling a little whole-some respect for "Kultur" into the villagers. Unfortunately, his class was likely to be a small one, for everybody had fled with the exception of three old women, two girls, two old men and four or five children.

Nothing daunted, he and his men set to work upon the principles officially laid down by his Government, with the gratifying result that before nightfall the two old men had both been shot for trying to defend their womenfolk from insult; one girl had been outraged and had escaped somewhere after shooting the man with his own carbine, and the remainder had been reduced to a state of mental and physical paralysis.

Thus the night passed without further incident. But in the early morning the outposts fell back upon the village with the news that British cavalry had been seen in considerable strength moving in their direction. With a hurried order to the senior sergeant Captain Schniff made his way to a small outhouse at the end of the village where the field- telephone line ended, and in a few seconds had informed his brigade H.Q. that he was expecting an attack in force at any minute.

It came before he had removed the receiver-cap from his head.

Three sudden shots and Captain Schniff, running out into the street, found himself in the middle of a whirl of men and horses. Half his squadron had mounted, the rest had just got hold of their horses when the wave of British cavalry swept in from the south. A troop of the 9th Lancers, acting as advance guard, had driven in the outposts, and not knowing, and caring less, what the enemy strength might be, had galloped straight at the village.

A few minutes of mad cut and thrust and the old people were avenged. The Lancers cleared the street from end to end almost in a single sweep. By the little outhouse door stood Schniff, pistol in hand. His first shot brought down a trooper with a bullet through his chest. His second tore a cut through a horse's shoulder. Then the wave swept over him. It passed; but the German captain still stood against the lintel, pinned to the wood with a sabre thrust clean through the neck.

Ranks were re-formed, two or three scouts sent forward to the north, and a message was despatched to the main body to report. There with the 9th Lancers were the 18th Hussars, and a brief debate followed as to whether they should push on or hold the village for a spell. The Colonel in command of the Lancers knew fairly accurately the enemy strength in cavalry in the immediate neighbourhood, and the odds against the British were rather heavy.

However, the point was soon decided for them. Captain Schniff's telephone message had been promptly acted upon, and some four new German squadrons were already well on the way to support their comrades. Our outposts fell back in their turn with the report that the enemy were approaching fast from two sides.

A squadron of the Hussars was at once sent forward with orders to dismount and get under cover ready to open fire as they saw the best opportunity. The Lancers were formed up clear of the village, but still out of sight of the advancing Germans. The joking and laughter have for the moment died away, and every man sits as though carved in stone with that curious, empty feeling inside which will always creep over one when waiting for the moment. Officers nervously fidget at the reins and try to appear unconcerned as they rack their brains for a sentence or two of encouragement or warning for their men. The Colonel is well out to the front carefully judging the ground and distance. There is a gentle dip in the ground which his eye at once tells him is the spot where the shock should conic. That extra down gradient will be worth to him a score more men.

We'll get them all right," a subaltern says over his shoulder. " They always pull in a bit when we're on them." lie had been through it before with his men, and knew about that odd, sudden shrinking which seems to attack German cavalry at the critical moment. The men knew too, and they instinctively settled to a tighter grip in the saddle, every eye on the man who was to lead them. The eternal seconds passed and the tension grew till it was well-nigh unbearable; just as when a bowstring is slowly drawn back until it seems that the yew will surely snap.

Suddenly the Colonel sees that the moment has come. The enemy are diagonally across his front, and it may be possible to meet them before they can fully change direction. The signal is given and the Lancers have started, so steadily that they might be entering the arena at Olympia for the musical ride.

The pace increases. The Colonel has given his men plenty of room, for they'll need every bit of advantage they can get. "Steady, men, steady! " The enemy have begun to wheel-Now!

One tremendous bound forward and the gallant horses are stretched out to the uttermost. Down the slope they thunder. Each man tries to pick an opponent, but there is no time. There is one mighty crash all down the line. The Lancers have got home. Heave! and they are through. Through, with hardly a check of the pace, and on. The files close in and the men begin to drag at the bit reins. A wheel into section, and so to the village, again.

The Germans, too, have checked and wheeled round, but they are not so steady. Though by far the heavier cavalry they have been badly mauled. It was like the little English ships sailing through and raking the great galleons of the Spanish Armada. Still, they recover and turn to retire the way they had come. Back they trot, re-forming ranks as they go. Now they have reached the northern end of the village. Now three hundred yards past, when there is a sudden burst of rifle fire and a hail of bullets ploughs through the hardly formed ranks.

(You had forgotten all about the Hussars, hadn't you?)

But the Germans know what discipline means, and they are courageous enough too. There is a momentary confusion, but a sudden word of command pulls them together, and about eighty odd men from the inner flank wheel about.

"By Jove! '' exclaims the Hussar squadron leader, "they're actually going to charge us." Then, after a moment to make sure, " Cease fire !-we'll wait for 'em," he adds to himself.

The other officers and N.C.O.'s see in a moment what they are to do. It is an old trick, but it calls for nerves of steel to carry it out. The Hussars had been firing "rapid independent" on the retiring Germans, and it is not always easy to get your men quickly in hand again, especially when there is an avalanche of men and horses coming down on top of you. Still, the Germans do not hold a grinding monopoly in discipline, and you might say that a crack British regiment will go one better, for the men are trained and disciplined as human beings, not machines.

"Not a shot till you get the word, and then two good volleys," sings out the O.C. "Aim low."

The German cavalry has covered 150 yards. They are getting alarmingly close, and coming for all they are worth dead straight. Again it is just a matter of seconds, but the O.C. is as cool as though it were practice on the Pir-bright ranges. 100 yards! And - "Fire!”

Every Hussar had picked his man, and that one volley accounted for practically the entire line of Dragoons. They say that only ten got back.

So ended perhaps the most brilliant cavalry engagement of the war up to that date, and, so far as I am aware, up to the time of writing. It illustrates very happily the mounted and dismounted work of our cavalry in those early days. All the world knows how magnificently they fought later in the trenches and not only our own Home cavalry, but those splendid men from India, the Deccan Horse, the Poona Light Horse, and other crack regiments.

The story, too, seems to tell of an adventure in some earlier war. Of a time when the enemy was worthy of your steel, and each faced the other for clean give-and-take fighting, with the better man to win. No rancour on either side, but a shake of the hand and a drink shared when it was over. Oh, the pity of it that the Germans cannot always fight so !

from a British newsmagazine : heroic cavalry charges