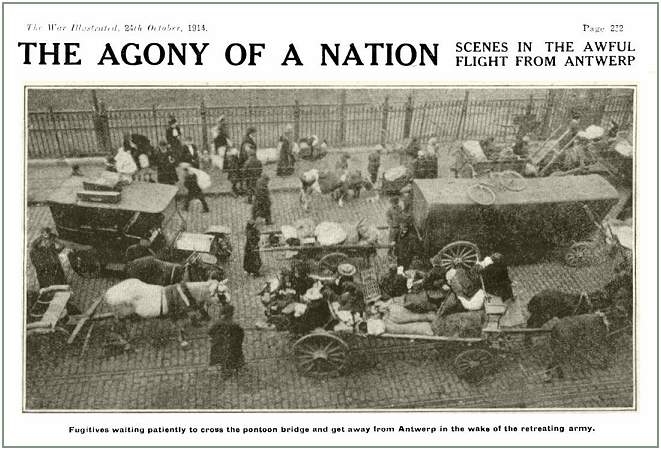

from 'The War Illustrated' 24th October 1914

SCENES IN THE AWFUL FLIGHT FROM ANTWERP

THE AGONY OF A NATION

Described by A. C. HALES

I am sending this account of Flemish terrors from a little village called Eckeren, close up to Antwerp, hoping to get it through Holland to London. On all sides terror reigns. The cry goes from lip to lip : "Antwerp has fallen !" and the despairing echo is The Uhlans are coming! God help us!

An official told me that all the best pictures in the city had been collected, by order of their King of the Belgians, to be transferred to London at once to save them- from the rapacity of the Kaiser's hordes. The city is on fire in many places, and the conflagration lifts up the kindly curtain that darkness has lowered upon the writhing of a people.

The scenes in all the townships and villages between Antwerp and Holland simply beggar description. Eckeren is sickening in its intense misery. Women of all ages are rushing about frantic with fear and misery; mothers looking for lost children gone astray in the panic; husbands searching for wives and little ones; old women totter along tire roads, moaning and wringing their hands; aged men, clinging to the arms of younger folk, stagger northwards, alternately praying to God and cursing the Kaiser. It is the most pitiful sights the sun ever looked down upon.

At Cappellen, the next township northwards, the sights were even worse. I saw an army of women practically demented by fear. They were as bad as the Macedonian women who fled in 1903 in front of the Turkish Bashi-Kazouks. Sick women and men were being carried on mattresses, preferring death from exposure to the tender mercies of the Kaiser's cavalry, who were expected in that direction as soon as the city fell.

At Heide and Cappelle-an-Bois the sights were heartrending. People worn with fear and running lay about sleeping - the sleep of semi-paralysis - little children who had been sundered from their parents and had been swept Holland-wards in the maelstrom of human anguish, crouched anywhere and anyhow, hungry, weary, and livid-lipped.

A few months ago all these places were peaceful and prosperous; now they are beyond portrayal. The terror of German deeds in Belgium is so great that the very fear of them coming has driven a homely, thrifty, kindly people to the verge of madness. The Dutch people seem to be doing all they can to help the famished, footsore wretches thrown helpless and homeless upon the mercy of the world, but it is a great strain upon their resources.

At Rosendale and Bergen-op-Zoom, the two first railway stations over the Netherlands frontier, there remained a horde of stranded waifs of all ages, sexes, and social standing. Every train that goes out is packed to its very utmost capacity with refugees, making anywhere and anyhow to some haven of refuge. No charge is made, no tickets asked for. Food is given by Government and the general public, but there is no bedding for hundreds; they just throw themselves down and sleep on bare floors, on tables, or out in the open, thankful to have escaped tire lances of the men the Kaiser is proud of describing as the finest cavalry in Europe. At Bergen-op-Zoom I beheld a sight that all England should have seen, and then I think volunteers would flock to the colors, not in hundreds per day, but in thousands, determined to crush the heathen tyrant who had made such misery possible.

The waiting-rooms and platforms were crammed with people, woe-worn and weary. On the side of the railway line there was packed a perfect mass of odds and ends that fugitives had snatched up in the moment of flight from home - and on or near this medley of household idols sat, stood, or lay the owners in scanty attire in the pitiless night.

Many of the women were sobbing with dry-eyed mournfulness that was a million times worse than tears. Now and again some poor wretch would rise and cry aloud the name of a lost child, and when no answer came the crier would crumple up and go down in a shapeless heap, her disheveled hair falling over her haggard face like a kindly veil.

They were good to the children, these poor, worn women. I saw one take off her jacket, and there was nothing underneath but a thin calico garment that left her neck and bosom bare to the raw night air. She had seen a little child nearly nude asleep by the railway line. The youngster was not hers, but they are universal mothers, these women. Thrusting the little one's legs through the arms of the jacket, she buttoned the garment round the body of the waif, and laid it very tenderly down to sleep in something like warmth, whilst she lay awake and shivered. This may not be the bravery of the battlefield, but it is the bravery that makes the other sort possible.