The Story of the British War-Horse from Prairie to Battlefield

Here is another human interest article from a British news weekly magazine. Or rather an equine interest article if you will. It is an interesting look at how horses were purchased and trained and cared for by the British Army during the Great War. This is a subject that is not given much thought. But when pondered upon, it is not at all evident how to procure and care for the millions of horses needed for the prosecution of an armed conflict the size and scale of the Great War.

Aside from reading the historical facts of the matter, this article is also interesting in that it (like many British and Allied articles) is full of subtle and not so subtle anti-German propaganda. The numerous asides, accusations and barbs aimed at the enemy appear nowadays to be quite immature taunting at best, and often not very believable at that.

Aside from the propaganda content it is also interesting to take note of the changing use of words. There are terms used in this article that were apparently considered to be quite normal usage at the time, but would now be grounds for a lawsuit.

Things change.

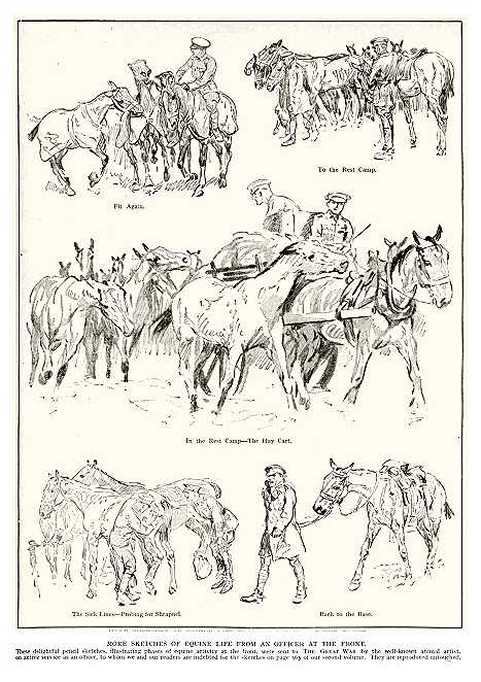

Illustration by Fortunino Matania

The Story of the British War-Horse from Prairie to Battlefield

by Basil Clarke

FROM time to time in the course of this history it has been necessary to glance for a moment at the services and sacrifice of man’s faithful friend, the horse.

Although motor traction has so largely usurped the ancient functions of the horse, it requires no more than a glance at the camera records of the war to realise that machinery has by no means eliminated the animal from the scene. Mechanical traction has greatly increased military mobility, but it has still left many uses for the horse and mule, and some consideration of how the supply of animals was maintained during the war, their manifold usefulness, and the organisation for their care is required in these pages.

“…his horse, his arms, his son, his wife." Such is the order of precedence of the Cossack soldier's main affections and when they talk of revenge upon the Germans the reason of their resentment is expressed not in terms of human lives lost or of country devastated or of towns razed flat, lint iii terms of horses. he will make them pay dearly," they say, for all the horses we have lost

This simple, as affection of soldier the Cossack for his horse noticed and expressed by a writer who had spent some time among them, would find nowhere a more real sympathy than among the soldiers fighting for Great Britain. This was perhaps natural. British soldiers were no more than maintaining a national tradition. To the British race the horse had long been more than a mere animal. For centuries he had had a place in their sports and pastimes and pleasures as well as in their work ; and by sheer merit of his own he had won a place in the British mind not only as a faithful servant, hut also as a friend and companion.

At the outbreak of the war British law and usage alike reflected the esteem in which the horse was held. There was no country in the world where abuse of him was more roundly punished, no country where so many voluntary agencies and agents existed to safeguard his interests and to see that he was not ill -treated. When war began, there fore, it was only natural and fitting that this British regard for the horse in peace should be reflected in the means and measures taken for his welfare in war and it may be said that not one of the fighting nations took greater care of their war-horses than did the British. How. their colossal army of war-horses was raised and maintained, and the great pains taken to look after the welfare of those horses, forms a striking item among the many great war achievements of the nation.

First, it will help towards a realisation of the enormous numbers of horses needed for warfare on the scale of the Great War if a few figures are given. The civil mind may find it hard to conceive that even an infantry brigade of four battalions; (about four thousand men) could not get along in the field with less than some two hundred and fifty horses and mules. Cavalry, artillery, and supply services needed horses, of course, in far greater proportion than infantry, and a division of i8,ooo men of all arms, infantry, artillery, transport, etc. (the unit used for purposes of supply and action in the field) needed, according to the official military standards in vogue in the year 1916, about 5,600 horses, distributed as follows

No great mental calculation is needed to conceive the immense number of horses needed for Great Britain’s Army of more than five million men, of which several million were on active service in the field.

How was this tremendous supply raised and maintained ? The outbreak of war gave to the Remount Department of the British Army, ably controlled by General Sir W. H. Birkbeck, the task of raising the supply of Army horses from 20,000 to 140,000 before the First Expeditionary Force was to move out of the country. Most of these horses were raised in the highways and byways of Great Britain itself. They were bought either with the owner's consent or without it in other words, they were commandeered, for no private interests could be let stand in the way, and a man who grudged sale of his horse found it taken by force and a fair price put in his hands. In justice to the nation, it must be recorded that the number of unwilling sellers was rare in the extreme. Many people were naturally reluctant to part with old favourite animals, but they saw the nation’s greater need and yielded them up.

For some time after the outbreak of war the stables and. country roads of Great Britain were one great mart for the buying of Army horses. The Government had appointed as their buyers men of repute and integrity and knowledge of horses, who acted in. an honorary capacity; They comprised well-known breeders and trainers of horses, well-known judges at horse shows, landed gentry, masters of foxhounds, and others who were in a position to know a good horse when they saw one and the price of it. Provided with a little black tin box containing a Government cheque-book, instructions as to what kind of horses to buy, and a written authority empowering them to commandeer any horse they thought fit, these men began a round of the stables of Great Britain with a keen eye (and a good price) for any horse that might serve their purpose.

Each buyer was made responsible for a district - generally speaking, his own locality where he knew, roughly, what horses existed and where they were to be found. To help him he was equipped with a copy of the latest horse census for that district. This document, which had been compiled in spare time by territorial adjutants, police, and others, showed the number and the owners of all horses that had existed in the district when the census was taken. It was far from accurate, of course, when used at this later date, but it was of great value, nevertheless, in showing the Government buyer who were the usual keepers of horses in the district, and where the horses were usually stabled. These addresses were at once visited, and a valuable first collection of horses was made from them.

It was noticed however that - perhaps owing to coincidence, and perhaps to human nature being what it is - many much-needed horses were never "at home" when the Government buyer called to see them, and before many days were passed the buyers found that they must amplify their visits to the stables by a keen look-out on the roads and fields. Many a farmer's dogcart and woman's gig was stopped on the high-road and its horse bought, as it were, right out of the very shafts.

The writer spent a day during the first week of the war with a Government horse-buyer in the roads of Essex, and saw several tragi-comedies of this kind for at this time people had not awakened to the seriousness of war, and could not understand why national necessities should be allowed to ride so roughshod over personal predilections. There might be many protests, but the horse was bought in the shafts as it stood. If the owner promised to forward the animal immediately upon his return home1 he was allowed to have the use of it td complete his drive. If not, the animal was taken forthwith and handed to soldiers who accompanied the Government buyer to take charge of his purchases.

As horses were bought in this manner, or in stables, they were forwarded each day to a horse-collecting station. Each area of the many areas into which the country had been divided for mobilisation purposes had one or more of these collecting stations. Like the organisation for buying horses, they were run on civil lines-manned and equipped by civilian labour, and in some cases provided free of charge to the nation by public-spirited citizens and local authorities. Thus a collecting station might be the yard of some big farm or the stables of some big house, or it might be a market-place or other public space lent by a public authority. As examples of collecting stations, one may mention Colonel Hall Walker's training stables at Russley Park, Marlborough, Mr. Bibby's private stables at Hardwick, and the market-place of Market Harborough, lent by the public authorities of that town.

By strenuous efforts in the different districts of England, horses sufficient for the mobilisation were got together in twelve days' time. In addition, the first. 150,000 horses sent out of the country were replaced as they went, and supplies sufficient for three months' war needs were obtained by impressment before the Government ventured to rely upon purchases in the open market for all the horses of which they had need.

But it was seen from the outset that, numerous as were the horses in the British Isles and their total even in 1917 was over two million - they could not be drawn upon to the extent that was likely to prove necessary without denuding the country of its home transport and power wherewith to keep going all the home activities necessary for a successful carrying on of the war In the same month, therefore that horse-buying in Britain began, special commissioners were chosen to go overseas to organise the purchase of the many additional horses that would be needed for an Army greatly increased in size, and to make good the high rate of casualties among horses which is inevitable in war.

The late Major-General Sir Frederick Benson, T.C.B., was at the head of these commissioners. He went out to America, and died there after organising a splendid system of horse-buying and seeing it well at work.

He began first in Canada, making his headquarters in Drummond Buikhngs St. Catherine Street, West Montreal) a little centre of activity that soon became known even in hustling Montreal as a place where business moved swiftly. Early and late, Sir Frederick and his helpers were interviewing the stockmen of Montreal, Toronto, and elsewhere, visiting their stockyards and picking out the best horses for the equipment of Britain's Army in the field. So well did they work that before the end of September shiploads of horses, carefully picked and tested for disease, were being picked and shipped from the Canadian ports to England.

When winter came the Commission moved southward to a warmer climate, and took up quarters at Newport News, in Virginia, later establishing a base also at New Orleans.

A horse-buying connection which had proved very successful at the time of the Boer War was renewed, and by means of it horse-buying for the British Army was soon a stirring. business throughout . all the neighbouring States of America.

It was realised by the Commission that they could not hope for the success and quickness and economy of buying at which they aimed if they worked in opposition to the huge stockyards of these parts of America, who after years of organisation had spread a network system of horse-buying right over the Southern States of America.

As an indication of the immensity of some of these concerns and their extraordinary facilities for buying, it may be mentioned that one firm alone, even in pre-war times, bought and sold about 130,000 horses and mules a year, the purchases of more than five hundred buyers distributed all over the country.

To have set up in business opposition to such concerns as these would have been merely to invite competition and overbidding. It would have necessitated the appointment of local buyers in great numbers. The British authorities had, moreover, the precedent of the South African War, and knew that they could depend upon the best stock-buying firms of this part of America for loyal service and a ''straight deal.''

Instead therefore of establishing a rival organisation to buy horses they linked up with some of the leading stockyards and worked in co-operation with them. The stockyard firms, for their part, entered into the bargain not only with loyalty, but with American business enthusiasm. They placed their big organisations and their immense stockyards and pastures at the disposal of the Commission. They railed oft separate pastures and erected new barns and stables, light railways, and all other things necessary for equipping collecting depots specially for British Army horses.

Some system of isolation of this sort was considered necessary owing to the special liability of American horses to a kind of influenza fever which is of a very infectious nature Horses were placed in these special camps for several weeks and observed closely for any outbreak of this fever before they were allowed to be shipped overseas, with the risk of bringing the infection with them.

To show in closer detail the work of the British Horse Buying Commission, it may be helpful to describe and give some account of one of these big American stockyards and the function that the commissioners exercised in it. The stockyards of the Guyton and Harrington Mule Co. will serve admirably for this purpose. With sales depots and feed stables in more than a dozen cities and hundreds of horse-buyers constantly out in the field, covering every State of the Union, this company could feed and stable on their own premises alone more than 100,000 horses and mules at any one time. This firm sold Great Britain some 113,000 horses and mules during the South African War.

Employing the same methods as at that time, they scoured the States of America for horses for the use of Great Britain in the Great War. Their buyers, each in his allotted district, went direct to the producer or breeder for his purchases and not to sales or markets. This method not only insured every animal being fresh, but also eliminated middle-men's profits.

When a car load or train load had been bought in any one locality the animals were despatched to the nearest depot of the firm. Here they were carefully examined both by the veterinary surgeons of the firm and also by the United States Government "vets."

Newly-arrived stock was isolated in separate stables, in order to rest and get in good condition, and to undergo rigid daily tests and inspection for sickness. Not until it was fit and guaranteed free from disease was a horse put forward for sale to the British Commissioners.

For the ordinary buyers auction sales were held weekly. These were open to farmers and any other horse-buyers, American or foreign, who cared to bid. The animals went into the auction-room one by one, and were knocked down to the highest bidder.

The members of the British Government Remount Commission, however, auctions were given special advantages. Certain stables were set apart that they might inspect all animals that were on offer and make a " first pick."

First of all members of the firm made a selection of such animals as they considered came up to the necessary standard in height, condition, and soundness set by the Remount Commissioners. No other animals than these were led before the commissioners, who then made an examination of their own, aided by the expert advice of British veterinary surgeons, one of whom was attached to each commissioner and buyer.

First the commissioner had each horse mounted and run to shown that it was properly broken in, had good action and wind and strength. Next the veterinary surgeon went over it, giving it certain tests. When both commissioner and veterinary surgeon were satisfied that the animal was sound it was led away to a special stable where the British brand marks were burnt on its hindquarters. The brand contained not only the broad arrow (common to all British government property from field-guns to pillow-slips), but also the initial of the buyer, so that responsibility for the wisdom of the purchase rested ever upon the buyer who had made it.

Next the horse went to the "roaching,'' or '’hogging," room, where manes were trimmed and tails ''squared.'' The United States surgeons then submitted each animal to a strict test for opthalmia before it was taken away to the British Army feeding-grounds to await shipment.

The names of a few of the men who served as buyers of horses for the British Government will give some index to the suitability of the experts chosen for this work. Besides military officers of the Remount Commission, all expert judges of horses, there were Mr. Alexander Parker, of the Hunters' Improvement Association, Sir Merrick Burrell, Mr. T. T. Fenwick, Mr. James Maher, Mr. Blennessett, Mr. Gordon Cunard, and Mr, Charles McNeill - names that were known wherever good horseflesh was known. The buyers, and the British veterinary surgeons attached to them, were provided with quarters at the. depots and stockyards, so as to be on the spot to inspect every horse that came in. The purchases, now branded as British and with the buyer's initial, passed on to the British depot some forty miles away, where they were kept and carefully fed and watched for a period of several weeks before shipment.

This place, which had been especially made by Major-General Moore for the British Army at the time of the Boer War and taken over by a private firm at the end of the war, was retaken for use in the European War and put in the control of Colonel E. de Gray Hassell, who organised the system by which horses and mules were shipped over to Great Britain. It comprised nearly thirty-six square miles of pasture lands, yielding the finest blue grass. Between its many low hills lay tiny springs of blue crystal-like water, pouring off into small streams and creeks. About the estate were stables, farms, grain elevators, and hospitals for every kind of sickness a horse is liable to.

Railways ran into the estate at various points, so that none of its many feeding-stations was more than three miles away from the central entraining point.

Probably at no other place in the world were there so many conveniences for the care of horses in large numbers. The natural springs and streams had in many places been dammed up by concrete to form artificial reservoirs. That no horse should have far to go for water, the streams and crocks had been supplemented by the provision of more than twelve hundred drinking-troughs, supplied by some twenty miles of two-inch piping.

For feeding the horses, immense hay storage sheds with iron roofs had been put up, capable of storing 5,000 tons of hay. There were also grain elevators, feed mills, and granaries, and, in the feeding-fields, haystacks, and feeding-troughs enough for 25,000 horses and mules.

Feeding-time at this depot was a thing that many visitors came to see. More than a hundred wagons, many of them pulled by four horses, scampered about the plains, and more than two hundred men were at work filling the troughs and hay-racks. The hospital accommodation included fine stables, special cookers, hot-water baths for horses, arid everything that veterinary skill could suggest.

The staffs at these depots comprised darkies of the Southern States of America and ''round-up men,'' or “chigoe boys," mounted on saddle horses. These men, the darkies especially, were keen supporters of the Allies' cause. They felt that they were an integral part of the British Army, and went about their work with keenest zest, with much merriment and shouting.

The " chigoe boys " in their caps and soft felt hats were especially picturesque. Mounted on beautiful horses, they were men of greatest skill both in riding and handling horses. Many were expert in the use of the lasso; and a frisky young horse who refused to be "rounded up" soon found his ''capers'' brought to a sudden finish by a noose cunningly thrown.

They also showed the liveliest enthusiasm in the work of policing and patrolling the feeding grounds, and any suspicious2looking person found about the stables and pastures met with the fiercest reception and handling. This work was really most important, for German agents tried every conceivable means to destroy British war- horses before they were shipped. In several cases disease germs were poured into depot Outrages or water supplies; in another case small steel German agents spikes, each of them barbed at the sides like the end of a fish hook, were mixed with oats intended for horse food. These, if swallowed by a horse, were calculated to perforate the stomach and bowels - a most barbarous thing to do to any horse. No outrage that was calculated to kill a horse or to give him disease that would spread to other horses - in fact, no outrage of any kind-was too bad for these German agents to attempt, and the watch maintained to prevent this sort of thing had to be most strict. The difficulty of proof of intent was, of course, considerable, and after one or two failures to bring home charges of outrages against persons strongly suspected the "chigoe boys" took justice into their own hands and any unauthorised person found near the horses or their pasture was well-nigh lynched This was rough justice, but it served very well.

When the time for sending a batch of horses down to the coast was nearly due the "chigoe boys " began a round up of the pastures and shepherded the horses needed for shipment into a central station. These contained pens leading out on to a railway siding. Each pen had three exits or "chutes," and every "chute’ faced a waggon of the train. A train of thirty long cars, each car holding twenty-five horses, could be loaded in thirty minutes.

Working on very similar lines to this were other British depots in different parts of the country, all under the personal supervision of members of the British Remount Commission, officer or civilian. Each depot, after conditioning its horses, sent them along to the coast. The train journey was made embarkation easier for the animals by stops at regular intervals for feeding, watering and rest ; for it was found that the long railway journeys of America, when taken without halt, made a horse in but poor condition for the trying sea voyage to Europe.

The chief port of embarkation used by the British was designed with the same efficiency and thoroughness as the collecting and conditioning depots. The wharves, half a mile in length, were covered with fine stables built of brick. Behind, were some square miles of pasture land and feeding-grounds. So ample was the accommodation that 12,000 horses could be handled in one day without difficulty.

The buildings were originally designed as fireproof cotton warehouses, but were converted into horse and mule stables purely for the purpose of shipping horses away to England. They were used for this purpose in the Boer War. On arrival by train from the British depots, away inland, the animals were driven down plank roads to enclosures behind the wharf. British veterinary surgeons examined each of them as it passed, and should any of them prove to have been injured on the train journey it was. picked out and placed in a "hospital pen" for surgical treatment. The sound horses were passed on into isolated pens and stables, where they were allowed to rest quietly for a day or two before being sent to the main feeding-grounds and stables.

So warm was the climate here that open-air feeding air the year round was possible, and animals bought from: the colder Northern States soon showed a great improvement in condition. Still some sickness was inevitable,. and plenty of work was forthcoming for the British veterinary surgeons who ran the horse hospitals here under the charge of Mr. A. Hunt, M.R.C.V.S.

Shipping day provided one of the busiest scenes. As the steamer drew alongside the wharf the whole organisation of the depot was busily astir. Members of the Commission were in the feeding-grounds behind, picking out on shipping day horses suitable for shipment. Noisy “chigoe boys" were catching them or roping them and leading them into special pens. At the wharves, meanwhile, a crowd of niggers and others were erecting timber chutes, long and sloping, leading from the wharf to the steamer's deck.

When all was ready, one or more members of the British. Commission took their places in the cut out station of each pen behind the wharf, and as the animals passed. before them, pointed out any which, on this closer examination, seemed not quite in condition for shipment. Any such animal was headed off into the "cut out," while the fit and well passed on. Thence they passed over a wooden viaduct to the wharf half a mile away. At the entrance to the wharf was a gate, at which stood a commissioner, who, with the aid of mechanical counters, assured himself' that the number of horses and mules thus delivered for shipment was correct.

On the wharf itself the horses passed through special driveways into narrow "halter-pens," where each was seized and fitted with a halter to take him on shipboard. With one man holding each horse's halter they were led. up the sloping "chutes" to the steamer's main deck, from which they were distributed about the ship and made secure.

In a British Government horse ship, which the writer of this chapter was given an opportunity of visiting, the' animals were loaded on two decks, each deck being under cover. There were some seven hundred animals on board, and the mules, as being the "tougher" creatures were given the lower deck, while the horses, more delicate and liable to lose condition at sea, were given the upper deck. The air there was considerably better than down. Below

The horses were packed in pens, five or six in a pen, with their heads facing an alleyway that ran round the ship. This alleyway was narrow, and to walk along it one had to push aside the heads of horses from both right and left of one's path. A vicious horse could have bitten one quite easily, for he had at his mercy anyone scrambling along the narrow passage. Yet not one of them seemed maliciously inclined. All good- temperedly moved their heads. aside for one to pass.

On the voyage the animals were under the charge of a "conductor," who, if not actually a veterinary surgeon by academic qualification, had nevertheless a complete knowledge of horses and their ways and ailments. Under him were some forty horsemen - a crew of tough Americans, some black, some white, who made the round trip out and. home with the boat. They were split up into gangs and. squads under foremen, and each gang was responsible to the "conductor" for watering, feeding, and otherwise caring for the horses in certain stalls every day. The conductor, in turn, was responsible to the shipping company and the Government, and his earnings depended on his success in bringing over horses without sickness or injury. Every horse lost meant a loss to him. He saw to it that horses were we]l fed and watered, and were given as good a voyage as might be.

At feeding-time the "horse boys" filled portable iron troughs with "feed" and squeezed their way along the alleyways, fixing a trough on the wooden bar under each horse's head. Water had next to be carried found, and each horse watered individually. To water a horse in a rolling ship, standing in a narrow alley with horses' heads all around one, each trying to force its mouth into your bucket, was no easy task.

Sometimes a horse might strain a limb wave on the voyage, in which event a sling was run to a roof bolt over his head, and he was given support to keep his weight off his legs. But no very complex surgical treatment was possible on shipboard, and little more could be done than to make the horse as easy as possible pending his arrival on land.

It might be thought that to horses standing. athwart ship in this way, the rolling of the ship would cause great hardship. When the rolling was severe this was the case, but a slight roll was regarded as more beneficial than harmful, in that it kept the horses mildly exercised, seeing that their leg muscles had to be constantly in use to enable them to maintain their balance.

Sometimes German submarines made a bid to sink British horse transports, and after a time it was found necessary to arm these ships with a gun or more and gun crews for purely defensive purposes. More than one good Army horse had his first taste of war and gun fire as he was crossing the sea from his native land. Some of them showed nervousness, others were calm and placid, and it was noticed that the calm ones seemed to reassure the nervous ones. Is it not so with human beings, too?

After days at sea, with all the adventures and anxieties that sea travelling during. the Great War had for sailors, a curious restiveness would become manifest among the horses below decks. It might be night-time. First would begin a restless tugging at head-ropes; then perhaps a beating of hoofs, which gradually increased, like the approaching of drums. The "horse boys" and officers took no notice. They knew the signs only too well.

The restlessness would increase. till at last the emotions of some horse found vent in a long-drawn whinny or neigh.

Land! He had smelt the land. It might be a hundred miles away, but he had. smelt it, and he gave vent to his joy in the only way he knew. He even tried to cut. a little caper in his narrow stall. Soon the cry would be taken up by horses on both decks all round the ship, and from the lower deck the queer, unmusical, almost pathetic trumpeting of the mules would join in the horse chorus of the upper deck. In every alleyway horses' heads would be tossing high, right to the beams overhead, and nostrils, widely dilated, taking in long sniffs of that new and welcome scent-the land. Even sick horses seemed. to brighten up after that great shout from their comrades. From that moment onwards the horses would be all impatience till land was reached.

In the case of the horse transport visited by the writer, the ship glided smoothly to the dock-side, and was met by nearly two hundred soldiers working under the direction of a Staff transport officer and officers of the Remount Department. Gangways for horses, or "horse brows,” as they are called, were run up from dock-side to deck. The "horse boys" of the ship,. quaintly dressed in sacks, and with cloths tied round their boots to prevent slipping, led Out the animals one by one from the alleyways With halters. They coaxed them up a sloping brow to the upper deck, and there banded them to soldiers, who piloted each horse down the "brow" to the' dock-side. In many cases it was the horse rather than the soldier who did the piloting for they were so. glad to get to land once more that they scampered down the brows, pulling the soldier with them. Others, nervous creatures, had to be persuaded and helped along, and one saw at intervals half a dozen "horse boys” - white men and darkies - literally pushing a horse up the brows and shouting like savages. The whole disembarkation Was done without mishap.

A veterinary officer examined each horse immediately on landing, and but for one or two animals that had developed disease. on the voyage, there were no casualties.

Before leaving. the subject of horse transport at sea, it may be mentioned that the. rate of sea-voyage casualties was very slight indeed, averaging barely one per cent.

Among the first 540,000 horses and mules landed from America the losses were no more than 6,000. Compared with the horse transport of some other nations, whose losses varied between seven and fifteen per voyage, and even more, this was a fine achievement indeed, and spoke well for the care expended on the work.

On arrival in England from the ships, the horses were taken to remount depots. Every port of disembarkation had its depots within easy reach. Some of these were old military remount depots, much enlarged to meet the increased demands upon them; others were quite new, specially established for' the war. Among the latter may be mentioned the civilian depots which by a stroke of the pen became military depots.

Mention was made. early in this chapter of civilian collecting-stations established at the beginning of the War for the collection of horses bought and commandeered in. England. When the commandeering of horses in Britain ceased some of these places were closed, but the best of them were retained and used for a time as civilian remount depots, working in touch with and exactly on the same lines as the military. depots. But for purposes of uniformity and control it was thought better that these depots should be made military if possible.

The idea was put to the men who manned them, and, with one accord, they voluntarily agreed to enlist right away. The masters of hounds, horse-breeders, and others in control of these depots were given commissions; the grooms, saddlers, farriers, and others who had manned them, were made privates and non-commissioned officers.

Thus, apart from a change on the part of the staffs from stable-clothes to khaki, the work of the depots went on virtually as before. Only slight changes were needed. The depots were standardised on Army lines. A hundred horses now formed a "troop," and its Military control of staff of twenty-five grooms and one all depots foreman became twenty-five. privates and one N.C.O. Five troops made a "squadron," each squad with its three officers, 165 grooms and riders, shoeing-smiths, "vets.," and N.C.O.'s.. But, apart from such changes in nomenclature, the taking over of the civilian depots brought about no great change.

It is worthy of record that one of the best civilian depots was run exclusively by women. After the. taking over of the depots it continued its work with the same staff, and worked on lines quite parallel to those of the depots it had now become military. Its staff had a khaki uniform of their own, and were, to all intents and purposes, a women's military unit. Many forage depots were also run by women.

The moment; horses landed in England the care for them begun in British hands over the water, was continued, and even increased. The veterinary officer, standing at the brow on the dock-side, had a quick eye for any. horses that did. not look up to the mark. They were promptly separated from their fellows, and sent straight to the depot infirmary. A "float" was at hand to carry off horses not able to walk. The strong horses were marched off to the depot by road. Their unshod hoofs on the hard English roads made an unusual patter. Arrived at the depot, they did not mix with other horses, but were tethered to horse-lines in an isolation camp of their own. Here they stood for two days under the closest observation for any symptoms of disease. Their temperature was taken;. and the 'mallein" test for glander - a sort of inoculation either in the neck or in the eyelid-was made. At any sign of a "temperature" or other symptom of sickness, a horse was drafted off at once to the sick lines.

After two days' examination, horses apparently fit were turned loose. Their joy on feeling themselves free at last was stirring to watch. Following the example of some leader, they careered about the fields like mad things, kicking up their heels; shaking their manes,. and neighing with all the spirit of youth on holiday. This, in fact was their holiday, their last holiday before beginning the serious work of war.

As they came back to condition and robust health they were drafted to the stables in batches. The dirt and mud of the voyage were still upon them.. First. they were scrubbed - literally given a bath with soap-and-water their hoofs cleaned, their manes cut off (unless they were meant for cavalry use), their tails "pulled," and their forefeet shod. Then followed a further period of feeding-up and conditioning, with nicely-graded exercises every day. For this purpose the horses were turned 'into a circular track enclosed by a double line of railings, in which two mounted soldiers, one riding. in front, the other behind' were able td exercise forty horses at once.

It was to be noticed that in each group of forty horses the same horse invariably took the lead every day, and followed in the Wake of the leading mounted soldier. What determined leadership among the horses was never discovered. It was not sex, for sometimes the leader was male, and sometimes female. Some close observers held that it was a question of "spirit", or "devil."

It was not until the horses had been in England for four five weeks, and had readied a thoroughly good condition - so good that some of them were more than eighty pounds heavier than when they left America - that they were considered as fit for issue to the fighting units. Carefully graded, according to strength, size, and condition, they were drafted off. to reserve units - cavalry or artillery, or transport to begin the learning of their war duties.

Here at least another six weeks was spent, and more in the case of cavalry horses, for there are many tricks in the war-horses' trade. Much patience and care must be expended on the teaching. Oddly enough, it was found that the best teachers were other horses; the skilled horse trained the novice.

Then came at last the great day when the horse was ready for the War zone itself. Three or more months had elapsed since its landing in Great Britain, and in many cases a horse, on leaving for the front, would hardly have been recognised as the same animal, so much altered for the better was it in both appearance and real condition.

It was taken to a British port of embarkation, of which several were used and rested there for three or four days before undergoing even the shortest journey overseas as, for instance to France, whither the great bulk of them went.

On landing, a horse received a similar rest at the depot of the port at which it arrived. Every British Army base had its remount depots, one or more; also a vast horse hospital for the reception of casualties in the field due to either wounds or sickness. Of these, more later.

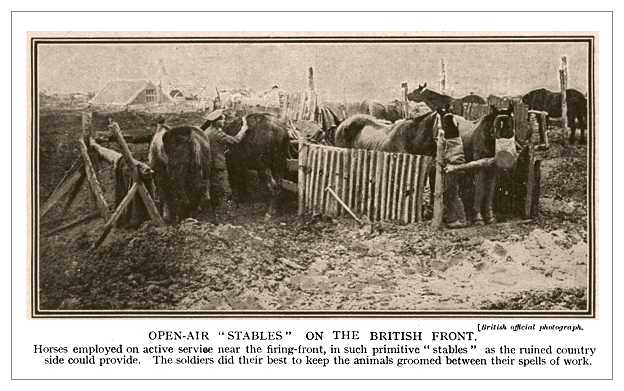

Horses from the base depots overseas were issued to the fighting troops as and when required to replace losses in the field. Every British unit whether infantry,. artillery, or transport, had one or more executive veterinary officers-attached to it. In the case of infantry of the line the veterinary officer attached to each battalion was to be found ever in. the neighbourhood of. the -nearest point to which horses were allowed to approach the lines.. Stationed at the "horse-lines" - or at Echelon R.- he kept an eye not only upon all transport and baggage trains moving backwards to rail-head - or rendezvous - for supplies, but also on the pack mules going forward with daily rations to points nearer the trenches. He had men of his own to correspond roughly with the stretcher- bearers attached to each regimental medical officer and his men, and he performed much the same services - for the horses of the unit as the medical officer and his men performed for the men. It was not to be expected, of course, that these veterinary workers could exercise quite the same degree of. supervision and surgical attention as was given to human beings, but very efficient care of the physical welfare of all war-horses was maintained, nevertheless.

These regimental veterinary officers nearest the front of the battle and their men were equipped with field-dressings, splints, and, the like for giving efficient first-aid to horses.

They might run moreover rough little field hospitals of their own for the treatment of minor, wounds and sicknesses not entailing a long curative course. They carried drugs and remedies for all the minor ailments that horseflesh is heir to, and, as a last resource, they carried one humane little weapon for putting a painless end to any poor sanimal so stricken with wounds as to be beyond hope of cure. This instrument was a Greener's Cattle Killer. Loaded with a powerful explosive charge it was capable of penetrating a horse's skull instantly. Held against the horse's forehead, one tap on the cap was enough-the suffering animal lay still, his sufferings over.

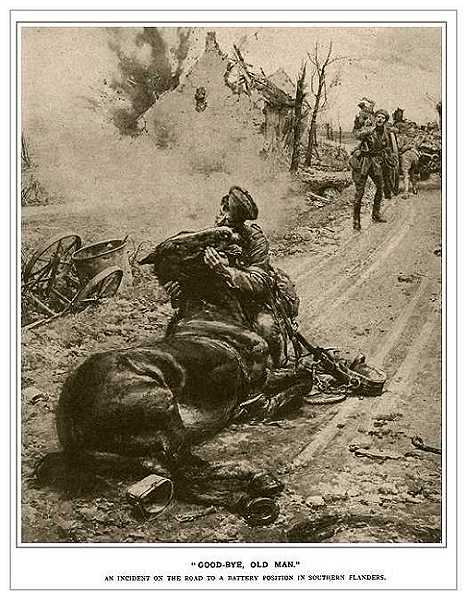

Many a merciful end to a wounded horse was given by officers in this way. According to regulation, it was for a veterinary officer alone to decide whether a horse should be killed straightaway or whether it should be kept alive for hospital treatment. But such was the concern of British soldiers for their horses that in many cases, where a horse was obviously wounded beyond repair, and the veterinary officer was not close at hand, a soldier himself performed this merciful office with his rifle. It was done sub rosa, of course, and men did not hesitate to assert that it was a shrapnel bullet or an enemy rifle-bullet that had struck their horse - so nearly and exactly between the temples - after he had been wounded in some other place. The veterinary officers knew better of course; but they were, after all, as human as the soldiers and kept their own counsel.

Many touching scenes occurred on the battlefields, not. only in France but elsewhere, where British soldiers lost horses in this way. Men who in times of shortage or danger had shared rations with their horses, or even risked their lives to save them from danger - as had many - British soldier could not come to this tragic parting without real sorrow.

One of the most human pictures of the war represented a British soldier on the battlefield holding up the head of of wounded horse and saying 'Good-bye, old pal !"

It was no mere flight of imagination on the part of the artist, for that scene occurred over and over again in actual fact.

Illustration by Fortunino Matania

While dealing with events here - near the forefront of the battle, it may be fitting to mention the good feeling and care which British troops showed towards the German horses which fell into their hands in the course of battle. Not only were: they kindly treated or humanely killed - if they had been left suffering by the Germans (as was often the case), but they were given surgical treatment if it was practicable; and many a horse that had fought for the Germans came to be the pet of some British soldier who regarded him as no less a "pal" because of his enemy origin.

It often seemed, as though the Germans had neither the time nor the means nor yet the wish, to look well after their horses. The diet they gave them was evidently not suitable, as was shown by the number of horses found dead with widely distended bellies. It used to be said out at the front in fact, that a dead German horse could always be told from an English horse by his distended belly. British horses were fed largely on corn. The Germans gave their horses too much, green food.

In close touch with every veterinary officer, posted to a fighting unit was the Mobile Veterinary Section, who performed for the care of horses much the same duties as -the field ambulance units of the R.A.M.C. performed for men. They had vehicles and men and officers for the collection of horses wounded in the field, and for transporting them either to field, hospitals for the treatment of minor wounds and sickness or to base hospitals for the treatment serious cases. These hospitals in the field were adjuncts to collecting stations from which wounded, horses could be sent by train down to a base hospital.

They had all sorts of up-to-date means and tackle for lifting horses and supporting them, besides surgical means for making every animal as secure and comfortable as possible for his journey down to the coast. Any cases capable of treatment at the collecting-stations were, of course, kept there and treated by the Mobile Veterinary Section themselves.

Other cases were packed off in long trains to the base hospitals. One sad memory picture which the writer brought away from the British front in France was of a long line of horse-boxes lying in a siding, each horse-box containing eight cases of horse casualties in the field. The animals were bandaged and splintered just like human beings. Some were supported by a broad band and were standing on three legs, the other being hung up in a sling. Some looked out with one eye through a casing of head bandages, but the big majority had their wounds naked, covered only with the stain of some antiseptic dressing; for it was found that horse wounds, in ordinarily clean surroundings, do better when left exposed to the open air.

The base hospitals for horses were either general hospitals or special, just as in the case of the men. There were special hospitals, for instance, for the treatment of mange and skin troubles. The general hospitals took all sorts of cases, surgical or medical, but each type of case was segregated with its own class. A big hospital visited by the doctor followed strictly a group system by which all cases of a similar nature were placed in the same stables or horse-lines, and put in charge of particular officers who had special knowledge and skill in the treatment of that class of case. Officers of the Veterinary Corps did not specialise in quite the same way as the officers of the R.A.M.C., one taking surgery, one public health, one skin troubles, and so on.

Members of the Veterinary Corps were supposed to have an equal skill all round, but in actual practice it was found that men showed a preference for one or other class of work, and had special skill in that class. Commanding officers tried as far as possible to find an officer's strong point, and to use it.

The hospitals were divided into wards quite on the lines of a human hospital, though very different of course in detail. The reception ward of this hospital was no more than a series of posts and ropes in a big enclosed field. The cases on arrival were taken to these reception lines, pending their distribution into separate wards suited to their case.

For the little ticket appended to each horse, showing his complaint - in some cases it was no more than a chalk-mark across his back - a disc was substituted. Upon it was written the date of admission to hospital, and then it was tied to the patient's tail. From the reception lines the horses were taken, according to their complaint, to. a surgical ward, or a medical ward or an isolation ward. These wards each of which was a great quadrangle surrounded with stables, was again subdivided. A surgical ward, which was really an amalgamation of several wards, was subdivided into the wounds, bullet wounds, foot wounds, and lameness, etc. The medical ward was subdivided again into groups or lines for catarrh,. strangles, pneumonia, exhaustion; general debility, etc.

In the isolation ward were segregated mange and other skin cases. As far as possible, heavy draught horses, light horses, riding horses, ponies, and mules were placed together in their respective groups, one explanation of this being the very human one that when a big horse is put next to a little one he is apt to reach over and steal his neighbour's food. This is less liable to happen when the other horse is capable of "reprisals."

To enumerate the many methods and appliances used in the treatment of wounds and diseases in British horse hospitals, in France would hardly be within the scope of any work save a veterinary history of the war.

One or two points. that struck the writer as being of more. general and human interest may, however, be recorded. Every horse undergoing painful operation at the hands of Veterinary surgeons was given an anesthetic. The writer saw, instance, a big brown mare lying on her side on a mattress undergoing an operation for some injury to the head.

A solid leather muzzle containing a wad of cotton soaked, in chloroform enclosed her mouth and nostrils, and although two white-coated surgeons were busy with instruments inside the skull itself, the good creature lay quiet, snoring peacefully. The four grooms who sat by; her extended limbs had no work to do.

In the isolation ward, which was entered by a narrow gap through which a man but not a horse could pass, stood a row of patients suffering from skin trouble. They were all a greeny-blue in colour, like that of German uniforms, owing to liberal baths and sprays with copper sulphate. Here .were special tanks for horses to bathe in and water-sprays, hot and cold.

Farther along, the catarrh cases were having. their noses and mouths swabbed out with soothing lotions. In a neighbouring ward men were hurrying along with little bags of steaming linseed for application as poultices to the 'strangles’ cases. In the surgical wards were poor old fellows standing patiently on three feet, holding up a painful fourth limb. Beyond were horses with great open wounds in various stages of cure. Such is the healthiness of the horse that a wound will begin to granulate and heal very rapidly after it is caused. The surgeons left them, where possible, without any covering.

This could not have been done save in clean and healthy surroundings; but in the matter of cleanliness the care exercised in British horse hospitals at the war was well-nigh as great as in the hospitals for men. Not a speck of dirt was to be seen, the horses themselves were scrubbed spotless before admission to the ward.

A disinfecting plant, generating a heat of 226 deg. centigrade dry-heat, was available for the disinfection of all halters. and horsecloths that might be likely to lead to infection. There were even arrangements for the care of horses' teeth, and the writer saw one poor creature who had been off its food for months, and was now restored to good appetite and a quickly-increasing fatness simply by repaired teeth. Its teeth it seemed had been turning inwards and hurting it every-time it ate. Therefore it would not eat. After a dental operation, it picked up amazingly and its appetite said its attendant, was now more like a mule's. The appetite of mules and their catholicity in the choice of food was proverbial among our soldiers at the front.

But after recovering from an illness, a mule's appetite became a fearful and wonderful thing. A hospital groom pointing out such an animal to the writer said, "He eats and he eats, he eats the wood of his stable and he eats even the rope he is tethered by. He likes poultices and he seems to regard newspaper and print as a special luxury. He has his Daily Mail regular every morning, and eats it with his breakfast!"

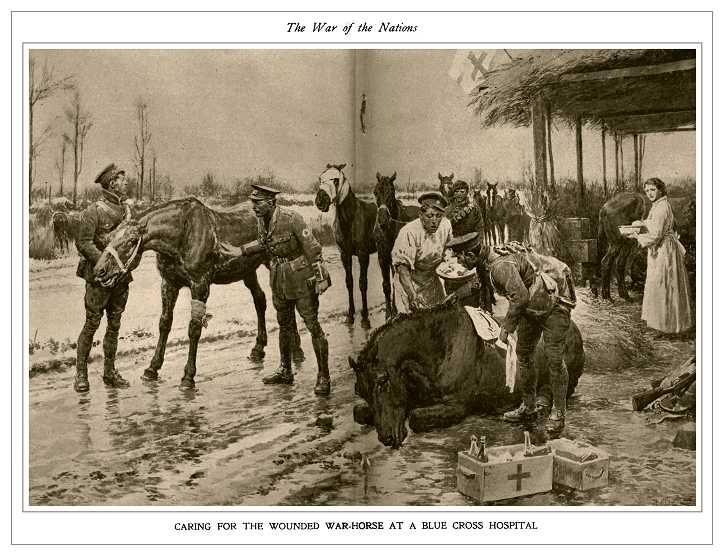

Supplementing the British Army's measures in the field for the welfare of horses were those of different voluntary organisations in Great Britain, and no record of this subject would be complete without mention of the war-work of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and of the Blue Cross Fund. The "R.S.P.C.A., as it was familiarly called, greatly assisted the British Army Veterinary Corps by erecting and equipping horse hospitals in the field. Financed by voluntary contributions of private subscribers, they were able to supply hospital equipment and means on far more generous lines. than would have been possible. to the Veterinary Corps themselves, working with strict regard to the exacting requirements of Government regulations and Government auditors.

To the normal comforts allowed by the Army Regulations these societies added others, with the result that British field hospitals and base hospitals were more complete and comfortable for their dumb patients than those of any other army in the field.

Then the Blue Gross Fund, founded under the aegis of Our Dumb Friends' League, of which the president was the Earl of Lonsdale, one of the best friends that the British horse ever had, supplemented the good work of the R.S.P.C.A for British horses by supplying many special drugs, veterinary requisites, and horse comforts to the various British regiments.

They made a point of supplying a number of things that were not always included in the Army scheme of provision for horses - little extras which made all the difference between treatment and "kind treatment."

More than a thousand units had to thank the Blue Cross Fund for their extra supplies of veterinary requisites - for the horse rugs, chaff-cutters, portable forges, humane killers, and such things. They received sometimes letters from officers in the field, and even from privates, saying what a difference these extras made to the comfort of horses; and it was characteristic of the British regard for horses that the writers wrote as warmly and as enthusiastically as though the gift had been a personal one to themselves.

The Blue Cross had no regard for the nationality of a horse. They erected, equipped, and worked a series of hospitals for the French Army, whose arrangements for the care of horses were hardly so complete as those of the British Army. Their hospitals at Moret, St. Mames, Provines, La Grande Romaine, Faviere, comprised in all some thirty huge wards, and were models of their kind; in fact, the French themselves used to say that the British Blue Cross hospitals had set a new standard to the French Army in the humane treatment of horses. The society was the means of establishing similar treatment for horses of the Italian Army, and gave grants to supplement the funds raised for this work in Italy. The Belgian Army horses also benefited by the gifts of money and stores from the fund.

One of the Blue Cross measures in other fields of the war is deserving of special mention. Its provision of fly-nets for horses wounded in the Near East brought an incalculable relief to stricken animals. Thousands of flies swarmed in the open wounds of horses causing an agony of restlessness which often resulted in the horse's death front sheer exhaustion.

The careful treatment meted out to British war-horses, not only in the field, but even from the first moment of their selection and enlistment for the purposes of war had a commercial as well as a moral value. British horses, thanks to the time and trouble taken upon their care, conditioning and training, arrived in the field, in better condition than the horses of any other army, and were in fact, looked upon with wondering admiration not by our Allies alone, but even by the enemy. As good results of this care, the horses, in the long run, cost less, owing to fewer losses from disease, debility and exhaustion in the field and, secondly, they yielded a more efficient service.

More than once, in emergencies, the British were saved by the wonderful efficiency of their horses. Mr. Beach Thomas, in one of his war despatches in the "Daily Mail," described how plans. for a German attack in a new place were suddenly discovered. He went on to explain. how urgent and vital it was that the British artillery should be shifted to more advantageous positions if they were to repel the attack. The ground was a quagmire, with guns up to their axles in mud. Time was pressing. They must be moved somehow. He continued:

‘Our Horse Artillery bumped and lurched and tore their way forward over holes and dykes and deep mud and slush. Picked teams of splendid horses, excited as a hunter on a hunting morning, dragged their hearts out in this noble venture, and an hour before the Germans' charge was ready the guns were unlimbered and in position. Who said that horses were no use in war ? We have lost many noble animals, but they have done their part indeed.’

Losses, of course, were very heavy. Of more than a million war-horses bought by the British Government previous to May, 1917, one in every four gave its life through wounds or disease. One hundred and forty three thousand died in France alone, 12,000 in Egypt 18,000 at Salonika, and 42,000 at home.

This was a very heavy toll, and various attacks were made against the Government in both the Press and the House of Commons on the score of these figures. It was probably true that at the beginning of the war a number of horses were bought that were not as good as they might have been. But in the rush to make good the Army's vital need for horses this was well-nigh inevitable. The first commissioners and buyers who went to America were faced with a similar need for urgency They had to buy not only the best of horses, but also the. horses they could get quickly. The Germans could not await battle while their enemy was picking and choosing horses. But after the first and most urgent demand for war-horses had been met - and it was met with amazing promptitude considering the circumstances - the buying became much more methodical and critical. The methods of transport were also systematised, so that losses were reduced to a minimum.

The high rate of casualties in the field was also made the ground for criticism, and the fact that more horses died from disease and exposure than died from wounds received in battle was hurled at the Government as conclusive proof of waste and lack of care. This was quite an ill-considered argument. To anyone who saw at close quarters the conditions in which war was carried on it became ground for wonder that more horses did not perish; Not only horses but men were standing, in France, for instance, up to their waists in mud for days on end in the most bitter of weather. To argue that the horses should have had protection and. cover is to argue that the horses should have had better treatment than was possible even for the men.

The horse, though so strong of bone and muscle, is an animal of delicate constitution. He is as liable to coughs and colds and lung troubles as any human being, and probably more so. That far more horses did not die in Flanders and in the mud of the Somme was testimony to their original fitness.

A most conclusive and detailed answer to those who criticised the Government for their treatment of horses was given by the Under-Secretary for War, Mr. Macpherson. Replying to Colonel Sanders in the House of Commons on August 1st, 1917, he said it was true that more than a quarter of a million horses and mules had been destroyed or cast or sold in the various theatres of war in the previous three years. This wastage worked out at less than one and a half per cent per month on the monthly strength of horses since the outbreak of the war. Commercial firms using many horses estimated that every year they had to replace twenty out of every hundred horses used. The wastage in the stables of two of the largest railway companies during 1916 was nineteen and a half per cent and seventeen and a half per cent. Respectively. The figures of wastage in the British Army were, therefore, extraordinarily small. They have never been approached in any campaign in history. The loss of horses bought in America had been five per cent., and at sea one per cent.

A large number, however developed influenza or pneumonia in spite of veterinary care. Considering the variety of adverse circumstances, including infections and attempted poisonings by enemy agents, one could only marvel that the loss had been so small. It was due chiefly to the system of keeping our horses till they were "salted" or clear from infection that we had attained the remarkably small figure of one per cent. loss on shipboard, which was a quarter of the loss at sea during the South African War.

British figures were believed to compare more than favourably with the losses that had occurred both on land and sea among the animals bought by our Allies in the same market.

Such facts as these were conclusive, and before them all attacks upon the Government's methods petered out.