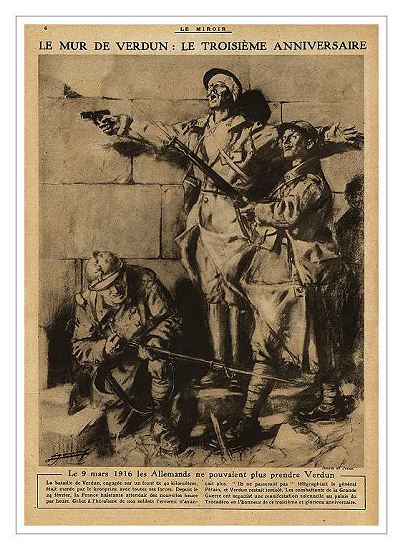

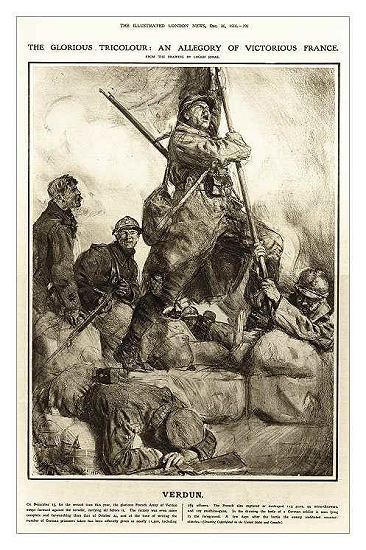

- from ‘The War Illustrated’, 21st October, 1916

- 'the Right View of Verdun'

- by Winston Churchill, M.P.

the Meaning of the Battle of Verdun

- evocative allegorical symbolism - France triumphant at Verdun

- two illustrations by Lucien Jonas

The second of the series of articles on "The War by Land and Sea" which Mr. Winston Churchill is contributing to our contemporary, the "London Magazine," appears in the issue for November, just published. It is one of the most remarkable and deeply interesting articles we have read on any phase of the conflict. It shows a wonderful grasp of the complexities of the war, and the ability to convey to the reader something of that clear-eyed view which the writer himself so obviously possesses. Nothing more illuminating could be written about Verdun than Mr. Churchill's summing-up of that tremendous episode of the war in this most noteworthy contribution to the "London." He shows with a deft literary art, that conjures up in a few swift sentences the dubious position of the Allies at the opening of the present year, how great indeed had been Germany's military conquests. He then proceeds to expose the enormity of her strategic mistake in launching the Verdun attack, and writes:

The attack upon Verdun dominated the whole German military policy of 1915, and ruined it. With the decision obstinately persisted in to make a grand offensive against Verdun fell Germany's last hope of escaping unscathed from the astounding adventure into which she had plunged.

A great German offensive in the west had long been the best thing that could happen to the Allies. Never was there a moment when it was more timely or more helpful.

Germany's Fatal Strategy

But that was not all. The German offensive against Verdun was, it soon appeared, to be combined with an Austrian offensive against Italy, opening somewhat later. And thus, both north and south, the Central Powers turned away from the eastern frontiers and, leaving Russia to recover behind them, plunged into desperate adventures in the west.

German armies, backed by artillery fire surpassing all previous record, are launched in mighty strength upon the apex of the French lines in front of Verdun. The high tactical skill of this great operation of war can be admired., But the vast strategic misconception on which it rested was fatal.

Having assembled and contrasted a few of the reasons, true and false, which we may imagine to have operated in the councils which led to the planning of the German attack upon Verdun; and emphasised, first, the wrong strategic impulse towards the west; and, secondly, the attempt to maintain a continuous decisive offensive against armies greatly superior in number and unsurpassed in quality, Mr. Churchill continues :

We may sum up the German enterprise against Verdun as the efficient tactical execution of a wrong strategic policy. It was based upon an organisation of guns and field railways perfect beyond all previous conception against particular points which we may call "anvils." Nevertheless, it opened by surprise. It was at first conducted on a system of limited attacks which minimised as far as possible the superior losses of the assailants. In spite of all this it failed—even locally and tactically. But even had it succeeded locally and tactically, it would have been disastrous to Germany, lor in this War tactics, however adroit, cannot redeem misdirection in strategy and policy.

But as the struggle for Verdun developed and the skill of the attack was met by an equally skilful defence, and as the unshakable constancy of the French produced resistances beyond all that had been expected, obstinacy began to clog the wheels of German thought. Reputations of the greatest authorities became first engaged then deeply involved in the fortunes of the enterprise.

Vast Process of Waste

The operation dragged. The scientific methods of the opening were succeeded by much less careful assaults. New floods of human life were poured out for insignificant gains. The whole German campaign in every other quarter was paralysed. The flower of the German armies was cut down.

Desperation then laid hold of those who were responsible. They saw their personal positions compromised. They had begun by endeavouring to persuade the French to attach a fictitious, sentimental importance to the fortress. They very soon began to attach a wholly unreal importance to it themselves. All their great influence and power over the German war direction was now concentrated upon finding new legions to be flung into the attack.

The vast process of waste continued far into the summer, and all the time the French High Command watched the process with increasing confidence, and the British Army gathered its strength. And all the time the Russian power revived and waxed again into a mighty world factor.

Samson's locks had been shorn in the autumn, but by the summer they were grown again. Along every road which was open the ceaseless stream of munitions from the arsenals of so many lands flowed to arm the teeming manhood of the Russian people. And Germany's hour had gone.

It was at this moment that the Austrians chose to engage themselves in a costly offensive in the Trentino.

Offensive and Defensive Losses

We may now consider the German Verdun offensive from the point of view of relative losses.

It is always easy for commanders, in default of more tangible gains, to assert that they have inflicted enormous losses upon the enemy. The Germans are adepts at this. But no assertions of theirs, however brazen, can alter the disproportion of loss between the offensive and the defensive. The defender naturally holds the sector of the line exposed to attack with the fewest troops possible. He knows they are going to be pounded to a jelly by the bombardment. The fewer men he has in or near the trenches exposed to drum fire the less his loss. He therefore keeps no more than are sufficient to compel the enemy to attack in full force, and to support his machine-guns. In the right solution of this problem resides the skill of the defending commander. On a sector of, say, 12,000 yards, one man to the yard will be a fair allowance for the front system of trenches, and an equal number in support and reserve. In other words, two full divisions will, apart from special circumstances, hold the line as well as it can be held. To load up the trenches with additional masses of men will only be to give the attacking artillery their heart's desire. The defence will be made no stronger if the trenches were crowded with double or treble their number. On the contrary, their slaughter will only demoralise the rest.

The attack, on the other hand, must have great numbers. To maintain a continuous assault on a 12,000-yard front from eight to twelve divisions or more might be required in a two days' battle. Thus, on a moderate computation, it may be said that five or six men are exposed in offensive action for every one in defence. When and where the attack is successful the losses are very heavy on the defenders of the trenches taken. Many are killed by the bombardment, many are bayoneted by the assailants; . some fly, the rest are captured. But the total number of these on any long stretch of front is greatly inferior to the losses of the assault.

When the trenches have been stormed the process of consolidation begins. Here again, the attackers suffer far more than the original defenders. They are much more numerous, they are in unfamiliar ground.

French Military Skill

All the parapets are in reverse, and in this situation they are exposed to an intense artillery counter-fire by gunners who know every inch of the lines they are firing at.

The attack therefore loses excessively—first, before the assault, by having to keep much larger numbers under bombardment in their own trenches than the enemy; secondly, during the assault by having to pass much larger numbers of men through the barrages and machine-gun fire across No Man's Land; thirdly, after the assault (if successful), by having to consolidate a strange position in crowded confusion under accurate and intense fire.

The defence, as we have seen, loses a high proportion of its relatively small numbers when the assault comes home. It also loses almost on the attacking scale when counter-attacks are launched. But the frequency and the weight of counter-attacks depend upon whether the defenders are really determined to win back and hold every part of the ground, and arc tied to fixed positions, or whether they are willing to cede a little at a disproportionate cost to their enemies.

The French showed the greatest military skill at Verdun in their defensive operations. But they suffered more than the defence need suffer by their valiant and obstinate retention of particular positions.

Meeting an artillery attack is like catching a cricket ball. Shock is dissipated by drawing back the hands. A little "give," a little suppleness, and the violence of impact is vastly reduced. Yet, notwithstanding the obstinate ardour and glorious passion for mastery of the French, the German losses at Verdun greatly exceeded theirs. And the excess of German losses would have been sensibly increased if at any time the French had though it right to allow themselves a little more latitude in regard to relinquishing particular positions.