- from the British magazine

- T.P.'s Journal of Great Deeds

- MAY I, 1915

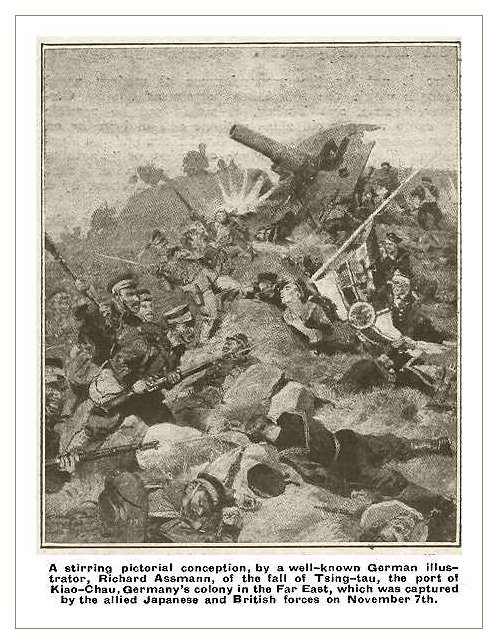

The Arm of the Orient

Japan Wipes Out an Insult and a German Colony

IT is twenty years since the German Emperor warned Europe of the "Yellow Peril," and placed his signature to a picture showing the Western nations rallying for a crusade against the Dragon and the Chrysanthemum. Had he weighed his words with greater care it is possible he might to-day have in the Far East a foothold where now he has none. But men of "blood and iron" are invariably believers in the philosophy of the "present." Germany at that time was strong in union with France and Russia, so, laughing like a braggart, she thought she could threaten Japan. But a new light was coming into the eyes of the little man of the Orient and a new power unto his arm. Japan smiled.

The Coming of Germany

When the German threat of War in 1895 deprived Japan of the fruits of her victory over China; when later Germany goaded Russia to War, Japan waited. She too, had a "Day," though in a very different sense, and that day of reckoning has come in the Far East earlier than Germany expected.

On a flimsy pretext of two murdered missionaries, Germany had established herself on a valuable strip of the Shantung Peninsula. Swiftly this new possession evolved from an array of carelessly arranged huts to broad streets and tree-shaded avenues, named in the same untiring way after the manner of the Hohenzollern brood. Tsing-Tau became Westernised, and German civilisation was represented by giant forts with great guns. The mailed fist of militarism controlled the town's outworks and its modern harbour. It was not for the improvement of China that Germany had come.

But still Japan smiled and waited, never forgetting nor forgiving. With quiet dignity she played her part in the Councils of the world. Britain held out a hand of friendship to her during trying times. It was accepted, and the grip was held firmly when the testing time came. Days passed into months and months into years.

The Warning to Go

There has never been much doubt as to what part Japan would play in the giant conflict so far as Eastern interests are concerned. From the Council Chamber in Tokio came the ultimatum to Germany telling her to evacuate Tsing-Tau and giving her seven days in which to come to a decision. It was a dignified message, worthy of a people that had known how to keep its temper. But it was a message reminiscent of Germany's note to Japan in 1895, and it must have brought back memories to its recipients in Berlin.

While the seven days were counting out, the Samurai spirit was alive with the hope of years, and the naval stations were busy preparing the fleet for sea. One, two, three squadrons lifted away from her harbours, and in the Yellow Sea and on the trade- routes in the Pacific they patrolled the paths of the merchantmen, watching the German boats and waiting for the end of the seven days and all that they might bring forth. Tokio was a buzz of excitement. Everyone was waiting as though an eruption of Fujiyama might be expected at any moment. When on the seventh day no reply came Japan was at war. On August 27th a general blockade of Kiaochau was commenced.

Closing In

The bombardment had begun three days earlier, and already the occupants of Forts Moltke, Bismarck, and Iltis were beginning to understand the marksmanship and the metal of their Eastern enemies. By September the investment of Germany's Far Eastern fortress had commenced, and for the first time in history British and Japanese troops were fighting side by side. With the South Wales Borderers and some Sikhs, General Barnardiston had joined the Japanese 18th Division, and the command of the Allied Army was placed in the hands of General Kamio.

A violent storm hindered the work of investment; but by September 28th, fighting all the way, the Allies had full control of the Litsun Valley, and the Germans had been driven south behind the last range of hills but one outside Tsing-Tau. Towards this final barrier of defence the trench-line moved forward under the continual fire of the great guns on the forts.

The Beginning of the End

Then on the dramatic night of November 1st the final assault began. Sapping by night - digging zigzag trenches about three feet wide at the bottom and four and a half at the top-and relentless bombardment from dawn till dark were the order of the next five days, the first three of which were stormy and bitterly cold. Each night the sand bagged heads of the saps drew nearer to the redoubts, till at some points the enemy's lines were only 200 yards away. The British faced Redoubts 1 and 2. To their right were General Johogi's men to their left, facing redoubts 2 and 3, General Yamada's and further to the left General Horinehi's. The whole Allied front measured, roughly, five miles.

Charmed Fearlessness

It is to General Yamada's quick perception that the suddenness of the fall of Tsing-Tau is due. On the night of November 6th he had sent some companies of sappers to attack Redoubt 3, and with charmed fearlessness they carried out the duty he had assigned to them. By one o'clock the fort was in Japan's hands. General Yamada saw at once that this was the moment. He telephoned to General Headquarters advising a general assault, and before waiting for further orders launched an attack against Redoubt 2. Now on all sides the Japanese and the British advanced. The men of Nippon tensed up to the fever of the charge, crying “Banzai," and led by General Yamada himself, about whose body was wrapped a Japanese flag which he had brought from Japan, and intended, an he lived, to place on the captured parapets of Germany's fortress.

Breaking Through

Everywhere the attack was successful. The British, despite obstacles of artillery and barbed wire, had broken through the enemy’s defences, and in a flood of cheering were up to the last line. With this final harrier before them, the attackers were preparing for the desperate attack an attack they knew would cost them dear, for the German defences bristled with armaments - when suddenly there came a great anti-climax. The German firing died away and a white flag trickled out on the air above Forts Moltke and Iltis. The Germans had surrendered-surrendered at the moment when they could have poured a devastating fire into the Japanese ranks, for our Allies were beneath their guns.

It was a tame surrender after the boast of weeks, in which it had been declared that Tsing-Tau would hold out until the last man, the last cartridge. Immediately the flag of surrender floated in the breeze the Japanese, cheering wildly, were swarming into the forts.

Sweeping the Pacific

Apart from this splendid capture of Kianchan, Japan has done other work for the Allies. Her warships played their part in heading off the wild-bull rushes of the Emden, and convoying our transports bound for the nearer East and the Homeland.

Despite the departure of the War from her sphere of vital interest, she is watching the trend of events in Europe, and, as one of her prominent statesmen stated recently, her legions and her fleet are at the service of those who in her infancy guarded her welfare.

"Look East," said the Kaiser in those dead years, and now as we look we see, not what he imagined he saw-a Germanised China-but a faithful friend and ally, a nation that has wiped out an insult and a German colony.

D. M. D.