- from the book

- 'the History of the Great War'

The Operations Around Kiao-Chau

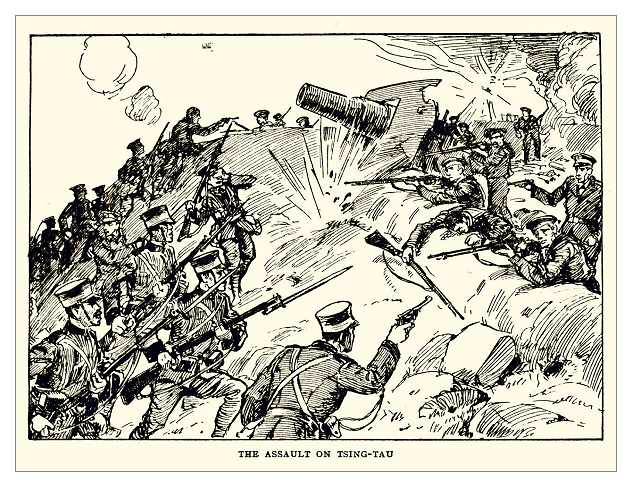

Japanese assault German positions at Tsing-Tao

CHAPTER XLVIII

The Operations Around Kiao-chau - Why Japan Went to War - Opening Stages of Operations - Germans Preparing for Defence - Landing of Japanese and British at Lao- Shan Bay - Preparations for Close Attack - The Exploit of the Rennet - Bombardment and Storming of Tsing-tau - The Surrender

The causes that led up to the siege of Tsing-tau form interesting reading.

At the suggestion of the British Government, that a casus foederis had arisen under the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, the Japanese were asked what they were prepared to do in helping to safeguard the British mercantile marine in the Far East. With unhesitating promptness they replied that the first thing necessary to restrict German activities in the Far East was to reduce the fortress of Kiao-chau. And on August 15th the Japanese sent an ultimatum to Germany demanding the surrender to Japan by September 15th of the leased territory of Kiao-chau. The document also called for the immediate withdrawal from Far Eastern waters of all German warships. Germany was given until August 23rd to accede to these demands. In order not to alarm the Americans, it was suggested that the lowering Of the German flag in China should not mean that a slice of Chinese country should fall under the sway of the Mikado, but that the territory torn from the Teutons should once more be restored to its rightful owners, the Chinese. In carrying out this the Japanese were engaged in work that, in a way, was a labour of love, for, needless to remark, the Japanese had not forgotten that the Germans were foremost in wresting from them the legitimate fruits of their victory over China, viz. Port Arthur.

When Germany, with the aid of Russia, had succeeded in doing this, on a very slender pretext she seized upon Kiao-chau, and though outwardly informing the world that they only had the port on a lease from China, it was pretty evident that the Kaiser intended to hold it, and, if necessary, extend it if the opportunity came his way.

Germany had also done all in her power to prejudice Japan in the eyes of the world, and for several years the cry about the Yellow Peril had been a booming din in Germany. It was therefore obvious that the Japanese were quite ready to use all their efforts to remove German influence from the China Seas, and they were well aware that the capture of Kiao-chau, on fortifying which vast sums of money had been spent, would for many years absolutely cripple German trade in China, much to the advantage of the progressive Japanese merchants.

Failing a satisfactory reply to their ultimatum, Japan commenced to invest the German stronghold on August 24th, 1914.

The opening stages of the operations against Kiao-chau were carried out with the silence and secrecy that always is part and parcel of Japanese warfare. The Mikado's seaplanes were the first of his forces to make themselves objectionable to the Germans, and by dropping bombs upon certain of the Government buildings they not only did a great deal of damage, but spread consternation in both the native and European quarters of Kiao-chau. In addition to this, other Japanese aircraft did excellent reconnaissance work, and, notwithstanding the fact that they had to withstand considerable bombarding, they all returned safely and with a large amount of valuable information.

Meanwhile the beleaguered Germans had been feverishly engaged in completing, as far as it were possible, the defensive works that were under construction. Their mining boats and improvised mine-layers were sent out to completely block the harbours and also put down a number of floating mines in Lao-Shan Bay. These, of course, had to be cleared where possible, and a number of Japanese boats were employed in this work, doing their duty very courageously.

The number of Japanese detailed for the work of capturing the town and forts was, of course, carefully concealed, but it was known that it consisted of detachments from all the finest fighting regiments of the Mikado's army, well provided with artillery, cavalry, and aeroplanes; many of the latter had, by a strange piece of irony, been constructed by German aerocraft firms. In addition to the Japanese it was decided to send a British expeditionary force from Wei-hai-Wei, under the command of Brigadier-General Barnardiston, consisting of South Wales Borderers and the 36th Sikhs.

On September 18th the Imperial Japanese troops destined for the siege were safely landed at Lao-Shan Bay, the vast flotilla of transports providing a fine spectacle as they disgorged their thousands of hardy little fighting men. With characteristic energy the Japanese engineers constructed piers for expeditiously landing the soldiers, and a city of tents and huts quickly sprang up under the beetling cliffs. On September 24th the small British force was also safely put ashore. Preparations were now quickly pushed forward, the heavy Japanese artillery were prepared, and by September 26th the main attack was fairly commenced.

The Allies drove the German outposts from the high ground between the Pai-sha and Li-Tsun Rivers, and by the following day had so far succeeded that they had occupied the right bank of the river seven miles north-east of the fortress. At dawn on September 28th the Allies again instituted another successful attack, and later in the day had seized the heights but two and a half miles from Tsing-tau, the port established by Germany on the peninsula forming the northern entrance to Kiao-chau Bay. In rear of the town were the fortified hills Bismarck, Iltis and Moltke, designed to afford protection on the landward side.

The preparations for the close attack were now actively put in hand, the big siege guns were placed in position, and during the first week in October fire was opened upon the enemy's main position. The Allied squadrons now commenced to take a very active part in the work of reducing the fortress.

Previous to this it had fallen to the lot of a British ship to first draw the fire of the German batteries; the destroyer Kennee, whilst chasing the German destroyer S 90 attached to the port, approached too close to the batteries, and received one shell on board, which, unfortunately, killed three of her crew and wounded seven.

On October 14th the Allied squadrons commenced to throw their heavy shells into Tsing-tau, and portions of forts Iltis and Kaiser were destroyed. Of the British ships taking part the most powerful was the battleship Triumph, 11,985 tons, armed with four 10-inch guns and fourteen 7.5 quick-firers; supporting her was the Minotaur, an armoured cruiser of 14,600 tons, and carrying four 9.2-inch weapons and ten 7.5-inch; behind her came the 10,850 - ton Hampshire and the light cruisers Yarmouth and Newcastle. Of the Japanese, the array of vessels available was numerous, and though their latest and greatest ships were not risked in the mine-infested waters, the craft detailed for the work were quite sufficient.

From October 14th to 31st storms considerably delayed operations, but on the last day of the month the Allied squadrons were again able to concentrate their fire upon the beleaguered fortress, great damage resulting. Fort Iltis was now a mass of debris, and from the town rose vast columns of smoke from the oil tanks that had been set on fire by the shells.

From land and sea the bombardment continued unceasingly until the night of November 6th; elaborate preparations for assault were made by the bombardment and Sapping up to the outer line of defences. Then, during the darkness, the Allied troops suddenly commenced a violent assault, and a storming party, led by General Joshimi Yamada, captured the central fort in the main line of defence, taking over 200 prisoners. Further successful attacks were made on Chan Shan and other portions of the position, and in the furious fighting that took place in the darkness 440 Japanese were killed and wounded, whilst previous to this date the casualties sustained by our gallant Allies had amounted to 200 killed and 878 wounded.

Shortly after dawn all the main positions were in the hands of the Allies. Seeing that further resistance was hopeless, the white flag was hoisted on the observatory shortly before eight o'clock in the morning. Negotiations for the surrender were at once commenced, and on the following Tuesday the Allied force entered and took possession of Tsing-tau, taking at the same time 2,300 prisoners.

Thus terminated the German rule in the Pacific. Though not finished, the fortifications of Tsing-tau were thought to be sufficiently strong to withstand a much longer siege, and the quick termination of the operations, notwithstanding the Kaiser's dramatic appeal to the garrison to resist "to the last man," came as a surprise to the world. The successful end to the Siege was announced in Tokio on the morning of November 7th, and by midday the British and Japanese flags were flying everywhere, and that night the Mikado's capital gave itself up to rejoicing. In Berlin the news of the fall of their cherished Far Eastern stronghold was received with bitterness and anger. Always it had been regarded as the starting point for further German Far Eastern aggression in the future, and now this was but a shattered dream.

In the operations the Japanese Navy lost two mine-sweepers, a torpedo-boat, and the old obsolete cruiser Takachiho, which, on October 20th, struck a mine in Kiao-chau Bay and went down, carrying with her 271 of her crew. We had several casualties in our vessels in addition to those killed in the Kennen, but did not lose a ship. During the entire land operations, lasting six weeks, the Japanese had a total of 1,500 men killed and wounded, the British forces losing 12 killed and 61 wounded.