The Times History of the War

Volume 2

Chapter XXXIII

THE DEFENCE AND FALL OF ANTWERP

THE FORTIFICATIONS AND PLAN OF DEFENCE-POSITION DURING THE GERMAN ADVANCE ON PARIS - CAPITULATION OF GHENT - BELGIAN ARMY RETIRES ON ANTWERP - SORTIE IN FORCE - FRESH GERMAN PROPOSALS TO BELGIUM MADE AND REJECTED - GERMAN STRATEGY-BOMBARDMENT OF MALINES - ANTWERP FORTS SHELLED - OUTER FORTS FALL - SITUATION IN THE CITY - GERMAN PROCLAMATION - GOVERNMENT PREPARES TO DEPART - BRITISH REINFORCEMENTS - REASONS FOR THE BRITISH EXPEDITION - CRITICISMS AND EXPLANATIONS - WORK OF NAVAL BRIGADES - RELIEF TOO LATE - GERMANS CROSS THE RIVER - GOVERNMENT AND LEGATIONS DEPART - GENERAL EXODUS - THE BELGIAN ARMY'S ESCAPE - COSTLY GERMAN DELAYS - THE BOMBARDMENT OF THE CITY - PLIGHT OF THE POPULATION - A DREADFUL PILGRIMAGE - DUTCH HGSPITALITY - FIRE AND DESTRUCTION IN ANTWERP - THE FORMAL SURRENDER - FATE OF THE NAVAL BRIGADES - GERMANV'S EMPTY TRIUMPH AND MILITARY DISAPPOINTMENT - BELGIAN HEROISM.

Antwerp, with its elaborate defences evolved through 30 years of addition to and improvement of Brialmont's original plans, was designed to be the great stronghold of Belgium: "the base of the field army and final keep of the kingdom." To this role it seemed to be admirably adapted by nature, with access to the sea on one side, and to landwards being practically encircled at an advantageous distance by the rivers Scheldt, Rupel and Nethe. The fortifications, with their successive developments, have already been fully described in a former chapter of this History. It will only be necessary now to recall that the "old" or inner ring of forts, placed at regular intervals of 2,200 yards at an average distance of about 3,500 yards outside the enceinte of the city itself, were planned, and mostly built, before the year 1869. The first of the "new" or outer forts (Rupelmonde, Waelhem, Lierre, Schooten and Berendrecht) were designed by Brialmont in 1879 ; while the final forts and redoubts of this series were only completed as recently as the end of November, 1913. The inner forts, like the defences of the enceinte itself, were excellently planned to resist the assaults of an enemy armed with the weapons of the period in which they were built, - namely, half a century ago. Properly held (as the Belgians could have been relied upon to hold them), they would have rendered Antwerp impregnable to direct infantry attack or to bombardment by the field guns of those days. The more modern outer forts, with the line of the rivers, would have similarly furnished a complete defence against any artillery that had been recognized as employable in field or siege operations up to the outbreak of the present war. Military authorities were entirely justified in believing Antwerp to be a position of practically incomparable strength. But the large German - or Austrian - howitzers, with a range exceeding any pieces which had heretofore been regarded as mobile, and far exceeding that of any guns mounted in the Antwerp forts, and with the extreme destructiveness of their projectiles, introduced a new element into the situation

Against them even the holding of the line of the rivers Rupel and Nethe, which had seemed so valuable a feature of the defensive works, was useless for the protection of the city. The average distance of the rivers from Antwerp itself is about 6 miles. The 28 cm. guns have an effective range of over 7 ½ miles, with an extreme range of some 2 miles more. As soon as the enemy could approach his guns, therefore, to the further side of the river, the town was at his mercy. So that all that stood between him and the capture of Antwerp was in fact the guns of the outer forts. And these themselves, as we have seen, would be helpless as soon as the enemy had placed his big guns in position against them.

This, then, was the actual condition of Antwerp as a defensible position when, towards the end of September, 1914, it began to be evident that the Germans meditated a serious attack upon it. But before proceeding to the narrative of that attack it will he necessary to give a brief survey of the events which had been going on in Belgium since the gallant defence of Liege, the fall of Namur, and the German occupation of Brussels, though some outstanding incidents of that period have already been touched upon.

As the mass of the German army swept southward in what was to have been the triumphant dash on Paris, there remained in possession of the Belgians as much of their country as lies between the coast and the line made by the river Scheldt from Antwerp to Ghent and thence by the river Lys to Deynze, thence to Roulers, Ypres, Poperinghe and the French frontier. To south and east of this line was a strip of debatable territory, which the Germans made no attempt to occupy with any permanent force, but which continued to be the scene of desultory fighting throughout the latter part of August and the whole of September. Some of the more conspicuous incidents which disgraced the German arms in the course of this fighting have been already mentioned, as the repeated and wanton burnings of Termonde and the dropping of bombs on the Convent at Deynze and other defenceless places. The Belgian forces throughout this period at any point along this line were insignificant. The army as a whole had been withdrawn within the fortified area of Antwerp, and the holding of this long front, even of the Important lines of communication by rail, road and water, between Ghent and Ostend, Bruges, Zeebrugge and other points, as well as the defence of the towns themselves, was largely left to the Civic Guards and the Gendarmerie. It was immensely to the credit of the vigilance and valour of these small, and often untrained, forces that the Germans, in whatever strength they sought to penetrate this front, never failed to find their opponents ready for them. This strength, it should be said, was rarely considerable. The chief object of the Germans was now to pour all the troops which they could send down to the main battle front in France, where unexpected difficulties had arisen. They evidently hoped that their methods of "frightfulness" had sufficiently terrorized the Belgians, so that they would not venture to provoke them to further "reprisals” by interfering with this process and, on those terms, they were for the present content to leave this unviolated portion of Belgium territory in Belgian hands.

Meanwhile fencing and petty skirmishes went on along the whole line. At one time (on August 26) a mixed force of a few hundred German infantry and cavalry approached to within five miles of Ostend, where. at a small engagement at Snaeskerke, they were pluckily driven off, with the loss of a material portion of their numbers in wounded and prisoners, by the gendarmes. Later (on September 25) an airship dropped bombs on Ostend itself, without causing any loss of life, and doing but insignificant damage to property. There were continual minor affairs at a score of different points, and in the early part of September these were so frequent and occurred simultaneously at so many points that there is reason to believe that the story told by Uhlans who were captured was true - namely, that a force of 1,200 Uhlans had been sent out with instructions to break up into smaller parties and, at all hazards, to get to the coast and find out what, if any, reinforcements of French or British troops bad been, or were being, landed at Zeebrugge or Ostend. The prisoners added that all members of the force who got back alive bringing any trustworthy information were to be decorated with the Iron Cross. It is certain that none earned the decoration; but for a week or so there was a very lively time at villages, cross-roads and railway crossings all up and down the front.

More serious was the demonstration against Ghent on September 6, when General von Boehn, in command of large reinforcements for the southern army. appeared at Oordeghem, some 12 miles south- east of Ghent, and sent on an advance force of some 5,000 infantry with machine guns towards the city with a view, presumably, to occupying it if it was found undefended. This force, however, found the Belgians well entrenched in a strong position between the river Scheldt and the line of the railway embankment at Melle, where a lively action took place. The Belgian loss, owing to superiority of position, was slight, amounting to less than a dozen killed and only a score of wounded. The wreckage of their machine guns left by the roadside and the size of the trenches in which the Germans buried their dead (two officers being buried in separate graves) showed that their loss was much heavier. They, as usual, burned, with the fusees which they carried for the purpose, every house in that portion of the long, straggling village which they were permitted to reach; then, under cover of night, they retired on the main army.

On the following day General von Boehn sent the Burgomaster of Ghent a summons to surrender under threat of bombardment of the city. The destruction of Ghent, just 100 years after the famous Treaty of Peace between Great Britain and the United States had been signed within its walls, would have been a crime which would have shocked the world even more than did the destruction of Louvain or Rheims Cathedral. The Germans were undoubtedly willing to perpetrate the crime, and to avert it the Burgomaster visited the German General at Oordeghem on the following morning, when a convention was entered into which provided that. on the one hand, the city should not ho bombarded nor should any German armed force enter it ; while, on the part of the Belgians, any soldiers that were in the town should be withdrawn and the Civic Guard disarmed, and in addition, certain supplies of grain and fodder, petrol and cigars should be furnished by the city to the German troops.

As the Burgomaster was a civic officer, the Belgian military authorities were afterwards disinclined to regard the convention as binding upon them. But it was, on the whole, sufficiently observed by both parties, and it undoubtedly saved the city of Ghent from, at least, partial demolition. And it was followed by other consequences

The whole episode served to advertise the fact that large German reinforcements were on their way south. The supplies requisitioned from the city of Ghent were, according to the convention, not to be delivered at Oordeghem, but at different points on each of the next two days ; on the second day, as far south as at Beirlegem, a village nearly 20 miles by road south-west of Oordeghem, and only about nine miles north-east of Audenarde. This sufficiently indicated the route which General von Boehn's force was taking. In fact, it did go as far as Audenarde, where it divided into two columns, and followed the same two roads to the French frontier as had been used by the first advancing German army. But the whole force did not get far upon these roads.

When the Belgian Army retired on Antwerp the King of the Belgians is believed to have declared that it should not again act as a field army in operations on a large scale. Its losses had been terrible in the early fighting, and the sacrifices, not only among the rank and file but among the officers, drawn from the first and oldest families of Belgium, had deeply touched his majesty's heart. He decided not to permit their repetition : a decision as honourable to the King as it was complimentary to the heroism of his troops. When, however, it was known that General von Boehn with his large force was on his way south an immediate sortie in force from Antwerp was determined upon.

Advancing from Termonde and Lierre the Belgian left recaptured Alost and pushed its way to and beyond Aerschot; on the right, issuing by Waelhem, it reoccupied Malines and penetrated to Nosseghem and Cortenberg between Louvain and Brussels. The connected story of the week's fighting which followed has not, and probably never wilt be, told, but it was undoubtedly the heaviest which took place in all this phase of the war in Belgium. The Belgian casualties were large. Antwerp alone, by the end of the week. contained 8,000 wounded, and many also were taken to Ghent, Bruges, and other places. But the German losses were greater. For some days it looked as if they would be compelled, and intended, to evacuate Brussels, and - the real object of the sortie - a great part of General von Boehn's force which had reached the other side of Audenarde hurried back over the road it had so recently travelled to help to repel the threat against the German position in Belgium. It was presumably this manifestation of what the Belgian Army in Antwerp was still capable of doing that decided the Kaiser to order an immediate attack upon that place.

It was characteristic of him, however, and it showed how little he understood the Belgian temperament, that, before facing the losses which the taking of Antwerp must involve, he should have ordered that another attempt be made to induce the King of the Belgians, even at this date, to consent to observe a species of neutrality. Direct negotiations were opened with the King in Antwerp. The intermediary selected was an eminent Belgian, resident in Brussels approached by General von der Goltz and asked if he would undertake to carry overtures to the Belgian Government suggesting that, in return for an engagement on the part of the Germans not to molest Antwerp, the Belgian army on its side would remain quiet within the defences and refrain from harassing the Germans in their occupation of the country or from interfering with their communications with the main battle line in France.

The gentleman in question undertook the mission, while frankly declaring his conviction of its hopelessness. Hopeless, indeed, it was. Neither the King nor his Ministers gave the dishonoarable proposal a moment's consideration, and the message winch the intermediary took back to Brussels was terse and unmistakable in its tenour.

It is not easy to understand the strategy which determined upon a direct attack on Antwerp without any vigorous attempt first. to isolate it, at least to the extent of severing its communications with the coast at Ostend and Zeebrugge. So long as the roads and rail-way lines to those places were intact the way remained open both for the receipt of reinforcements and, if need be, - for retreat. Whether the Germans failed to appreciate until too late the importance of those communications, or whether they were deceived as to the strength in which they were held (which is unlikely, seeing that Belgium throughout all these weeks was swarming with German spies, who were continually being arrested in all sorts of queer and ingenious disguises, as priests, as Belgian soldiers, as rural postmen and a woman), or whatever the reason was, no serious attempt was made to cut the Belgian line anywhere west of Termonde ; a fact for which the Allies had cause in time to be abundantly grateful.

Simultaneously with the beginning of the attack on Antwerp, indeed, a demonstration of some seriousness was made on poor, stricken Termonde itself, resulting in fairly heavy fighting to the immediate south of that town on September 26 and 27. The fighting of the former day is known as the battle of Audeghem, from the village two or three miles to the south-west of Termonde, which formed the centre of the engagement. In the early part of the day a force of some 700 Belgian infantry, without any guns, was attacked at Audeghem by a much superior German force, which bombarded the village (especially, as usual, battering the church to bits) and succeeded in driving the Belgians out, inflicting on them a loss of about one-third of their total strength. The Belgians fought with extreme stubbornness, however, giving way only, as it were, by inches until early in the afternoon, when, being reinforced. they counter-attacked and drove the enemy headlong down the road towards Alost. In this latter part of the action the German losses were heavy and the Belgians took 117 prisoners.

The Battle of Lebbekke (from another village, lying to the south-east of Termonde) on the 27th followed much the same course, commencing with the surprise of an inferior Belgian force in the early morning, followed by the arrival of reinforcements and the complete rout of the enemy, who were driven back as far as Maxenzee and Merchtem, on the roads to Brussels, by the middle of the afternoon. A very considerable Belgian force had by this time been massed about Termonde and Grembergen, on the north side of the river, and the at that point.

Simultaneously with the fighting at Termonde, more attempts to cross the river were made at other points, from Schellebelle, on the west, to Baesrode on the east. They were made by small parties of Germans and were in each case repelled. All this activity may only have been intended to distract the attention of the Belgian army from the attack which was being prepared on Antwerp itself; but the earnestness of the two days' fighting at Termonde indicated at least a willingness to get across the river, so as to approach Antwerp from the west as well as from the south, if it could be achieved without too heavy sacrifice. The futility of the endeavour, however, was soon evident and the real attack on Antwerp was developed. The Allies were well aware of what was in progress, and the Belgian army within the defences made all possible arrangements to meet the attack.

By referring again to the map of the fortifications of Antwerp, published on an earlier page, it will be seen that the rivers Rupel (from its junction with the Scheldt) and Nethe, make a rough semicircle round the southern and south-eastern sides of the city at an average distance of about 6 miles from the walls of the town. Outside the line of the rivers, in this section, were, besides various minor defence works, the forts (counting from the west) of Bornhem, Liezel, Breendonck, Waelhem, Wavre Ste. Catherine, Koningshoyckt, Lierre, and Kessel. It was on these forts (though the first-named and the last were not at once engaged) that the initial attack was delivered, commencing on September 28.

On the preceding day, being Sunday, the Germans had advanced as far as Malines and had subjected the now defenceless town to a new bombardment. Characteristically, they selected the hour when the people were assembling for worship as the time for opening fire anti the Cathedral as their immediate target. The only possible justification for the attack was that the civil population was compelled to flee northwards to Antwerp, where its coming might embarrass the defenders. If this was the object, the citizens could as easily have been driven out of the town by mere occupation and proclamation, without the gratuitous cruelty of bombardment.

On the following day, Monday, September 28, as has been said, the German guns advanced beyond Maline. could reach the southernmost of the Antwerp forts, and it was on these - on Waelhem and Wavre Ste. Cathenne - that the brunt of the initial attack fell.

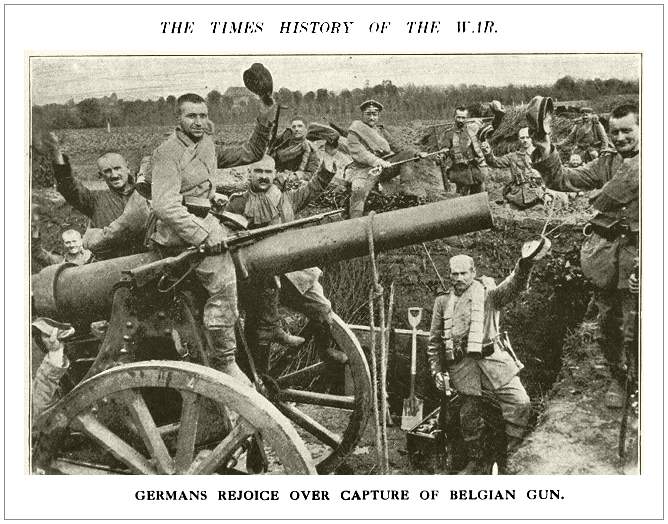

The actual forces which the German commander, General von Beseler, had in hand for the attack on Antwerp is not known. The Special Correspondent of The Times, who was in Antwerp during the siege and had access to the best information available placed the number at 125,000 men. After the fall of the place there was a disposition to minimize the force used, and it was placed as low as 60,000. Against this, however, is to be set the semi-official statement made in Berlin, in the exultation of victory, that the fall of Antwerp released 200,000 troops for use in the main theatre of war However many were it any time actually engaged, it is probable that 125,000 is not an overestimate of the force which was ready to be used. As a matter of fact, however, the decisive factor was not the weight of men but the calibre of the guns. No guns in any of the Antwerp forts or defences could range with the German 28 cm. howitzers. The inner forts in particular are believed to have been armed with nothing more formidable than 4-inch guns of an obsolete pattern, firing black powder.

Throughout the day and night of September 28, and on the following day, Forts Waelhem and Wavre Ste. Catherine were subjected to a truly terrific bombardment. The guns in the forts were backed by field batteries, which were skillfully masked in the intervals between the forts and at various points on the other side of the Nethe, and, putting the big howitzers out of the question, there was no evidence that the Belgian artillery was not fully able to hold its own against that of the enemy. It was, indeed, curious how little damage the German fire did, except, in these first days, to the forts themselves and, later, to the various villages which they successively bombarded and to the men in open trenches. On the other hand, there were occasions when the Belgian fire was conspicuously effective. But no skill or galantry could long delay the end against the superior weapons.

Wavre Ste. Catherine was the first fort to be silenced, on September 29. It had been badly battered by the big howitzer shells, which smashed concrete and steel cupolas alike, and half its guns were out of action, when the final catastrophe came in the explosion of the magazine. It is uncertain whether the explosion was caused by a projectile of the enemy or by the premature bursting of one of its own shells. Apart from the wreckage to the structure wrought by the explosion, the galleries were filled with fumes so that (or so it was consistently reported at the time) many of the garrison lost their lives and most of the rest, including the commander, were dragged out of the ruins, as had occurred also at Liege, half asphyxiated. New men were put into the fort, the gallant commander, it is said, insisting on returning with them; but it was found that no gun could ho effectively used, and Wavre Ste. Catherine was abandoned.

The German attack was now concentrated on Forts Waelhem and Lierre, especially on the former. Not far in the rear of Waelhem were the main waterworks of Antwerp, and on September 30 the enemy succeeded in destroying the waterworks and bursting the great reservoir. One of the curious sights of the bombardment was said to be that of a 28 cm. shell falling in the middle of the reservoir, with the enormous column of water which it threw up to an almost incredable distance. The bursting of the reservoir had two results. In the first place it flooded certain of the Belgian trenches, nearly drowned out some of the field guns, and made the carrying of supplies and ammunition to parts of the defence works very difficult. Second, it cut off the city's water supply.

Antwerp had, indeed, an auxiliary supply from artesian wells ; but this was quite inadequate to the needs of the population. All water for domestic uses had after this date to be carried from central points in pails and buckets, and the poorer parts of the town especially suffered severely. As there was no water in the pipes, the danger of fife was very great, arid even more serious was the threat of epidemic diseases arising from insanitarv conditions.

By the night of September 30 Walhaem Fort was badly crippled, but it continued to reply to the enemy's fire with such guns as could be worked throughout October 1. The defence of Waelhem, indeed, longer continued, was characterized by the samre tenacious courage as had been shown in Wavre Ste. Catherine. When the remnant of its garrison was finally compelled to relinquish it they left behind them little more than a shapeless heap of tumbled earth and steel and masses of concrete. They themselves had difficulty in getting away, one by one, by a ladder which made a temporary bridge across the moat. On the same day Forts Koningshoyckt arid Lierre were silenced after three days of almost continuous bombardment and part of Lierre village was set on fire by shells, the great volume of smoke rising from it in the still air being visible from the whole circuit of the fortifications.

There is some uncertainty as to the size of the guns used against the Antwerp forts. In Antwerp at the time, among the Belgian troops in the forts arid in the trenches, it was universally believed that the Germans had two or more 42 cm. howitzers in action. Colour was given to this by the undoubted fact that four of these great pieces had, shortly before, been laboriously brought back from Maubeuge northwards after that place had fallen. Their progress had been noted across the plain of Waterloo as far as Brussels, and it was generally opined that they were being brought for rise against Antwerp. But it is difficult to get positive evidence that they were in use there. The 28 cm. shell is such a formidable projectile - it spreads such havoc when it falls effectively - that it was easy for those who witnessed its effects for the first time to believe that it belonged to one of the very largest pieces. That the 28 cm. howitzers were employed against Waelhern, Wavre Ste. Catherine, Koningshoyckt, Lierre and Kessel - all the forts of tire southern section - is certain; and even before tire fall of these forts occasional shells were thrown from the howitzers among the trenches and batteries well across the river. The normal range at which they were used against the forts appeared to be 12,000 metres (7 1/2 miles), but the time- fuse of one which was thrown a mile or so across the river, and failed to explode, was said to have been set for 15,200 metres, or 9 1/2 miles. This is a materially longer range than the 28 cm. gun is commonly credited with being capable of, and it is possible that the Germans had in use some pieces intermediate in size between 28 and 42 cm.

With the fall of these outer forts - that is, from October 1, the situation of Antwerp became practically hopeless. The way of the attacking force was still barred by the line of the river Nethe, on the holding of which the defence was now concentrated, the Belgian troops withdrawing across the river on October 2, destroying the bridges behind them. But, as has already been said, it would not in fact have been necessary for the enemy to advance their heavy guns further than to within a mile or two of the river to be able to pound the city to pieces

The people of Antwerp in the mass had no way of gauging the seriousness of the situation. The firing was still so distant that, from the streets, it was only occasionally faintly audible in the stillness of the night. In the day nothing could be heard. But all day great crowds surged about the main thoroughfares of the town-the Avenue de Keyser, the Place de Meir, in the Place Verte and along the Quay - while all manner of contradictory rumours flew abroad. The local Press was, by authority, studiously and persistently sanguine, and the only evidences of the nearness of the enemy which the populace in general possessed were the abiding inconvenience of the shortage of water, the continued dashing of military motor-cars through the streets and the daily circling of aeroplanes - generally friendly - in the sky for purposes of observation. These from their height, were commonly visible from all parts of the city.

The visiting aircraft was not, however, always friendly. Early in the morning of October 1 an aviator circled over the outskirts of the town and dropped bombs without doing any harm in the neighbourhood of Broechem and Schilde. On October 2 a Taube flew over the city and let fall quantities of copies of a proclamation from the German commander of the attacking army to the Belgian soldiers. This document, translated, ran as follows

PROCLAMATION

BRUSSELS October 1, 1914

BELGIAN SOLDIERS!

It is not to your beloved country that you are giving your blood and your very lives; an the contrary, you are serving only the interests of Russia, a country which is only seeking to increase its already enormous power, and, above all. the interests of England, whose perfidious avarice is the cause of this cruel and unheard of war. From the beginning your newspapers, corrupted by French and English bribes, have never ceased to deceive you and to tell you falsehoods about the origin of the war and about the course of it; and this they continue to do from day to day. Here is one of your army orders which proves it anew! Mark what it contains

You are told that your comrades who are prisoners in Germany are forced to march against Russia, side by side with our soldiers. Sorely your good sense must tell you that that would be an utter impossibility ! The day will come when your comrades, now prisoners, returned to their native land, will tell you with how much kindness they have been treated. Their words will make you blush for your newspapers and for your officers who have dared to deceive you in such incredible fashion. Every day that you continue to resist only subjects you to irreparable losses, while after Antwerp has capitulated your troubles will be at an end.

Belgian soldiers! You have fought long enough in the interest of the Russian princes and the capitalists of perfidious Albion. Your situation is desperate. Germany, who fights only for her own existence, has destroyed two Russian armies. To-day there is not a Russian to be found on German soil. In France our troops are setting themselves to overcome the last efforts at resistance.

If you wish to rejoin your wives and children, if you Long to return to your work, In a word, if you would have peace, stop this useless strife which is only working your ruin. Then you will soon enjoy the blessings of a happy and perfect peace

VON BESELER,

Commandant in Chief of the Besieging Army.

The proclamation is worth publishing in full as a characteristic example of German fatuousness (in that General von Beseler should hope, after Germany's treatment of Belgium, that anything that he could say would influence the enemy's gallant troops) and German tactlessness, in the sneers at the patriotic Belgian press and the officers of the army who had shown such devoted courage and possessed the entire confidence and affection of their men. One sentence only of the document was, perhaps, approximately near the truth, namely, that which said that the situation of Antwerp was desperate. But the mass of the people and the rank and file of the army were very far from believing it.

In official circles, however, the seriousness of the outlook was recognised. On the afternoon of Friday, October 2, it was decided that the Government should leave Antwerp for Ostend. Two boats were ready at the Quai du Rhin. It was arranged that one of these should sail for Ostend at 10 o'clock on Saturday morning, having on board the members of the Government and the foreign legations. On the second the British and French Consuls. General, Sir Cecil Hertslet and M. Crozier, were to invite the members of their respective colonies to be on board by 5 o'clock on the Saturday evening, with a view to leaving for England either that night or early on Sunday morning. It was understood that this was a prelude to the evacuation and surrender of the city.

This, as has been said, was the plan on Friday night. Many of the Government officials and others slept that night on board, where nearly all their luggage was also taken during the night. By nine o'clock on Saturday morning (October 3) cabs and motor-cars were already leaving for the boat, carrying the passengers with their personal belongings, when suddenly there came a dramatic change of plan. The Government would not leave. The sailing of the earlier bat was countermanded, and it was given out that it had been determined to defend Antwerp to the last. The second boat, containing the majority of thc French and British colonies (though without Sir Cecil Hertslet and M. Crozier, who stayed behind), left according to programme. It was soon known that the ease of the sudden change of plan was the receipt of news that British reinforcements were on their way.

Not much of the foregoing facts was known to the people of Antwerp in general. None the less, a suspicion spread that the outlook was sufficiently gloomy, and from this date onwards there was a constant trickling away of the population, especially of the more well-to-do, chiefly by railway to Ghent, Bruges and Ostend. As for the soldiers, whatever they may have thought, they maintained the same gallant and cheery optimism as was characteristic of the Belgian troops through all the trials to which in the first months of the war they were subjected. Their courageousness and gaiety were the admiration of all who saw them.

One most important fact was that the Belgian soldier (as did the British, French and Russian soldiers no less) early acquired confidence that he was individually a better man than his enemy. This conviction, born of experience, was too universal in all the allied armies to be without foundation. However devastating the German artillery might be, and for all that the German massed troops would come heroically again and again to almost certain death, British, French, Belgian and Russian soldiers alike soon learned that, when it came to work at close quarters with the rifle or still more at even closer quarters with bayonet, lance or sabre, they were always more than a match for an equal number of the enemy. How much the moral strength created by this confidence counted for in the success with which, on countless occasions, the Allies in almost absurdly inferior numbers held and drove back bodies of the enemy which should have overwhelmed them, it is impossible to say. That it counted enormously is certain.

It is said that in the Revolutionary War in America the great importance of the Battle of Bunker Hill was that it taught the Colonists that, untrained as they were, their levies could fairly hold their own in open fight against the trained British troops, with their world-wide reputation; and that discovery was calculated to be equivalent to a multiplying of the American armies by four or five fold. Something similar to this happened in this war. The Allies soon learned that, so far as infantry attack were concerned, they had nothing to fear from much superior numbers of Germans. In Antwerp, as elsewhere, the result was that the Belgian soldier went daily to the front and to his place in the trenches lightheartedly, filled with a certain gay contempt for his opponent. only desiring to have a chance to get at him, serenely assured that at anything like reasonable odds he would have the best of it.

None the less, there had never been a time when the Belgian army had not been acutely aware of its hopeless numerical inferiority. It knew that the odds against it were not reasonable. And there had been no time when it had not earnestly longed for reinforcements, especially British reinforcements. It has been explained in an earlier chapter why the hope of the Belgians in the very first stages of the war that Great Britain would at once throw all her strength into Belgium itself had of necessity to be disappointed. In Antwerp this hope had grown again. Antwerp was easily accessible from Great ]3ritain, and it seemed to the Belgian army and people that here was an occasion, when a definite fortified position was being desperately defended against immense odds, where British reinforcements, even in such numbers as could be easily spared from the main theatre of war, could render a vital service to Belgium and to the Allied cause. At last the Belgian Government made a direct appeal to the British Government for reinforcements. In an official statement issued on October 11, Mr. Winston Churchill, Secretary of the Admiralty said :

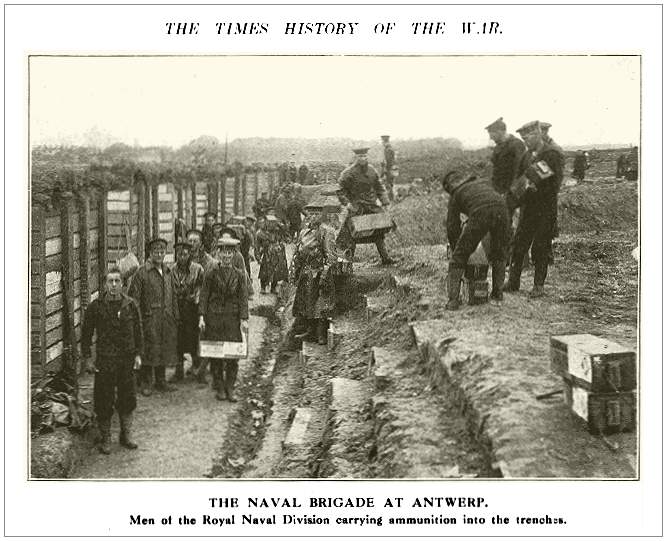

“In response to an appeal by the Belgian Government, a Marine Brigade and two Naval Brigades, together with some heavy naval guns, manned by a detachment of the Royal Navy. the whole under the command of General Paris, R.M.A. were sent by his Majesty's Government to participate in the defence of Antwerp during the last week of the attack."

Mr. Churchill himself accompanied the expedition, remaining in Antwerp nearly to the end, and on more than one occasion going under fire and visiting the men in the trenches.

As a result of these facts, coupled with the purely naval character of the force, there was a tendency in England to represent the expedition, after Antwerp had fallen, as in the nature of a personal adventure on the part of the Secretary of the Admiralty. and there was a good deal of criticism of “amphibious warfare'' Point and bitterness were lent to this criticism of Mr. Churchill bv the fact that a large proportion of the Naval Brigades consisted of very young men who had so recently joined and were so untrained that some at them literally did not know how to use a rifle. In not a few details the equipment also was sadly inadequate. It is evident, however, that such action could not have been taken without the approval of the Cabinet as a whole or the consent of the War Office. The reason why those particular troops were employed was explained in a message sent by Mr. Churchill to the Royal Naval Division on October 17, which, besides being a message of congratulation to the Division, was also in a measure a reply to the criticism which had been made.

He said: "They (the Naval Brigades) were chosen because the need for them was urgent and bitter; because mobile troops could not be spared for fortress duties; because they were nearest, and could he embarked the quickest ; and became their training, although incomplete, was as far advanced as that of a large portion not only of the forces defending Antwerp, but of the enemy forces attacking."

After arriving at Antwerp General Paris's command was, of course, under the direction of General Deguise, the officer commanding the defending army.

The first detachment of British troops reached Antwerp late in the evening of Saturday. October 3, and the effect on the people of the city and on the Belgian soldiers was electrical. Not only were the khaki- clad companies received with the greatest enthusiasm by the people, but - “for the first time since I have been here," wrote the Special Correspondent of the Times in Antwerp on October 4, "I have heard the Belgian soldiers singing triumphantly as they marched; not a few or a single regiment, but every troop that passed through the streets swung along joyously singing. And for the first time since I have been here everywhere the crowds rushed to cheer them. I sincerely believe that it is no exaggeration to say that every Belgian soldier in the trenches today is worth three of what he was yesterday."

The melancholy fact had soon to be recognized, however, that British help had come too late. Whether the number of troops that were actually sent, with the guns that they had, would at any time have been of material assistance is another question. It has been said that "with five times the number of men and ten times the number of guns sent a fortnight earlier, Antwerp could have been held indefinitely." That is probably true. Mr. Churchill has stated that "the Naval Division was sent to Antwerp, not as an isolated incident, but as part of a large operation for the relief of the city. Other and more powerful considerations prevented this from being carried through." In Antwerp itself it was believed by high military authorities until as late as October 6 that British troops, largely regulars, sufficient to bring the British contingent there up to a total of 35,000 men were close at hand. Precisely what troops and how many had been "earmarked" for dispatch to Antwerp, and exactly what the “other more powerful considerations" were which prevented their being sent, has never been disclosed. All that arrived seem to have been the Marine and Naval Brigades mentioned, or about 8,000 men in all, and some naval guns. It has never been stated that more than six of the guns were ever in action, two being mounted on an armoured train, and four of 6 1/2 in the neighbourhood of forts 3 and 4 of the inner ring. Arriving as late as they did it is very doubtful if a much stronger force could have been successful in materially delaying the inevitable end, except at the cost of the prolonged bombardment and wrecking of the city.

On October 2, as we have seen, the Belgian forces in the south-eastern section had been withdrawn to the right bank of the Nethe. As the outer forts had been silenced, the German guns were pushed up nearer to the river, arid by October 3 their shells were searching tire country as far on the road to Antwerp as the villages of Waerloos and Linth, and an extremely heavy fire was poured upon the Belgian trenches nearest to the river. Under cover of this fire the Germans made determined efforts to cross the river at Waelhem, and desperate fighting occurred there through the night of October 3 and the early morning of October 4, but the attempt to force a passage entirely failed. At one time in the night the enemy had succeeded in getting a pontoon across the river, and troops in solid masses hurried to cross it. Before any had reached the right bank the pontoon was blown to bits by the Belgian fire, and it is believed that in the losses suffered by the masses of German troops as they advanced to cross occurred the heaviest casualties suffered by either side in any individual incident of the attack on Antwerp.

Apparently discouraged by the experiences of the night, the Germans withdrew from their attempt to make a crossing at Waelhem, and turned t heir attention further east, to between Duffel and Lierre. Throughout the night of October 4 and the day and night of October 5 the battle raged about Lierre with great severity, British marines having now relieved the Belgians in some of the most advanced trenches at this point. These trenches were riot of a character to afford much protection against shell fire, and the position in which our untrained troops were placed was one which would have tested tried veterans. But British and Belgians alike did all that was possible. On the afternoon of October 5 the casualties from shrapnel fire, to which the men bad no chance of replying, were so heavy that it was decided to be too costly to endeavour to hold any longer the line of trenches nearest to the river, and these were evacuated in favour of a line a few hundred yards further back and less exposed. During that evening and night the enemy made repeated attempts to cross the river, only to be beaten back by machine gun and rifle fire. More than once small parties succeeded in reaching the right bank. only to be shot down, and it was not until 4 a.m. of October 6 that the Germans made good their tooting across the river. According to the official report of the British Admiralty, the circumstances in which the crossing was effected were that the Belgian forces on the right of the Marines were forced by a heavy German attack, covered by very powerful artillery, to retire, and in consequence the whole line of the defence was withdrawn to the inner line of forts."

The inner line of forts, however, old as they were even when supported by the British naval guns referred to, were quite incapable of resisting for airy length of time the assault of such artillery as the Germans could bring against them. They could doubtless have held out for some days - perhaps for a good many days - and any advance of infantry through the barbed wire entanglements and other obstacles, could have been made very costly. But it would only have been delaying the inevitable for a comparatively short space of time; and it must have been at the price of many lives, the probable surrender of either the whole or a large part of the defending force, and the more or less complete destruction by bombardment of the city of Antwerp. It was decided not to make any more prolonged resistance than would suffice to cover the retreat of as many as possible of the Allied troops.

Arrangements were made for the immediate departure of the Government and Legations of the Allied Powers for Ostend. Since the earlier abortive plan for the transfer of the Government, two packet boats - the Amsterdam and the Brussels had been kept in constant readiness with steam up. On the evening of October 6 the Ministers and other official passengers went on board the Amsterdam and the remaining members of the French and British colonies on board the Brussels, and both sailed early in the morning of the 7th.

On October 5, while the struggle for the Nethe still hung in the balance, the City Council of Antwerp had adopted a fine and spirited resolution, bidding the general commanding the defence to be guided solely by military considerations without regard to property interests in the city, and pledging him the support of the civil population. On the same day, however, both the Burgomaster and the general commanding issued proclamations, advising the citizens to leave Antwerp, and warning them as to the course they must pursue in case either of the bombardment or the entry of the enemy into the city. The public rightly accepted these as ominous of the serious situation of the city, and from October 6 onward great numbers of fugitives passed all day across the ferry which led to the Gare Waes arid the railway lines to Ghent, and not a few left also by vehicle or on foot along the road to the Dutch frontier.

During the night of October 6, also, the Belgian army began to be withdrawn. That evening and continuously thereafter there was a constant succession of troops of cavalry and carabineer cyclists and auto-mitrailleuses passing through the city, not, as heretofore towards the Porte de Malines and the front, but in the reverse direction-towards the bridge of boats which crossed the Scheldt close beside the ferry to the Gare Waes. The significance of this, however, was perhaps only partly understood, even by the soldiers themselves. Persistent reports of the nearness of the remainder of the 35,000 British troops continued to circulate, and in the army it seemed to be generally believed that the reason why they did not appear in the city was only because a great surprise was being prepared for the enemy. Instead of being brought to Antwerp, the reinforcements were engaged in a great enveloping movement on the German left, from the direction of St. Nicolas towards Malines, which would isolate the army besieging Antwerp and crush it against the defences of the city. Whether such a manoeuvre was truly in contemplation will only be known, if at all, when all the secret history of the war comes to light. Certainly it was believed in high military circles in Antwerp. Perhaps it was only interrupted by those other and more powerful considerations of which Mr. Churchill spoke. At least, the belief in it sustained the spirits of those who witnessed the last phases of the struggle for Antwerp with the hope that the nearer the besieging force approached to the city the more certain would be its destruction when caught between the guns of the inner forts and the assault of the enveloping troops.

If the plan had been in contemplation, however, it must have been abandoned before October 6. The Belgian troops, who on that day began to be withdrawn, were not detained to take part in any enveloping movement, but with some exceptions, as will be noted later on, were moved steadily, by road and railway, towards Ghent and on towards Ostend. The actual evacuation had indeed begun. Already all the larger German ships lying in the Antwerp docks - some 30 in number - had been rendered useless for immediate service by blowing up the machinery with dynamite. It was generally reported in the Press at the time, and appears not to have been contradicted, that the ships were sunk. This was not true. What was done was that charges of dynamite were exploded in the cylinders and boilers of the engines, necessitating long and difficult repairs before they could be made serviceable. On October 7 also, the oil tanks on the west side of thc Scheldt were set on fire. Antwerp was the oil depot not only for Belgium, but for much of Holland and the northern part of France, and immense stocks were stored there which it was plainly undesirable to allow to fall into the enemy's hands. At first the tanks were tapped and the contents allowed to run off; but this was seen to be too slow a process and in the night of October 6-7 the tanks were fired.

So on the morning of Wednesday, October 7, with the Government, the Legations, and all the members of the French and British colonies departed; the civil population, though not yet in any panic, prudently withdrawing in continually increasing numbers ; the defending troops coming in front the fighting line and steadily passing westward out of the city, and with the work of destruction of property which might be useful to the enemy already going on, it was evident that the end was near. Near, too. were the enemy’s guns to doomed city.

With his heaviest artillery, as we have seen, the enemy could indeed have reached the city without ever crossing the Nethe. It does not appear, however, that the 28 cm. howitzers were brought into advanced positions after they had done their work in battering the outer forts to pieces. The German official reports explicitly denied that these weapons were used against the city itself, and there is every reason to believe that this is true. Meanwhile the fire of the other heavy artillery drew daily closer to the inner defences. As early as October 2 the village of Waerloos had been under fire. In the afternoon of October 4 the first shrapnel l shells burst over Contich (about halt way between the river and the gates of the city), driving the householders in panic through the streets. The 5th of the month was occupied with the desperate fighting for the river between Duffel and Lierre, but on that day and on the 6th Contich suffered severely, and the villages of Hove, Linth and Vieux Dieu were all subjected to heavy bombardment. The village of Mortsel also was practically obliterated, not by German shells but by Belgian troops clearing the field of fire of the guns in the inner forts.

This is a fact which must be taken into consideration in subsequent calculation of the ruin wrought by the German advance. Not all the destruction visible was caused by German guns. It is said that, in preparation for the defence, within the whole fortified position of Antwerp (a radius of, perhaps, 15 or 20 miles from the city itself) no less than 10,000 buildings were levelled by the Belgians. It was evidence of the heroic spirit in which the civil population faced the hardships of the war that the officers who had charge of the work of demolition declared that in no single case did they receive any protest or complaint from those whose houses were destroyed. It was enough that the sacrifice was demanded for the welfare of their country.

Whether the destruction was wrought by friend or enemy, however, the effect on the inhabitants of farms and villages was equally to leave them homeless and to drive them into Antwerp for shelter. It has been said that tins was the effect on the people of Malines when that place was bombarded at the very commencement of the operations. Every day since then the stream of refugees into the city had increased in volume. By the night of October 6 practically the whole district from Malines to the walls of Antwerp had been swept bare of inhabitants, all of whom, who had not been killed, had fled into the city for refuge. Even before the end of September a great number of refugees had come to Antwerp. but in the 10 days from September 27 to October 6 the influx had increased until the population was swelled by certainly not less than 100,000 extra people. These counterbalanced the exodus of the real residents of the city who, in their turn, when the danger of bombardment began to be imminent, sought some place of greater safety, so that until the very last days Antwerp continued to he fully populated, and the crowds in the streets - especially along the Quays and in the region of the Cathedral and Place Verte - remained as dense as ever. On the night of October 6 and the morning of the 7th the exodus of the civil population, however, began in earnest. The defending forces, as we have seen, had fallen back within the ring of the inner or second line of forts, some of which commenced firing that night. It was no longer possible to go out of the city on the roads to Contich or Vieux Dieu any distance beyond the line of these forts.

On the morning of October 7 the streets of Antwerp presented an extraordinary spectacle. It was known that the city now lay at the mercy of the enemy's guns. Somehow a rumour had got abroad that bombardment was to begin at 10 o'clock in the morning, as if it were some new and portentous kind of theatrical entertainment. Notification of the intention to bombard the city if it was not surrendered had been sent to the defenders on October 6 and General Deguise had replied refusing to surrender and accepting the consequences. A request was also made by the German commander for a map of the city with the situation of the chief architectural and artistic treasures, as well as of the hospitals, marked upon it, when it would ho endeavoured to respect them as far as was consistent with the conditions of present- day artillery fire. Such a map was taken to him by the American Vice Consul, and copies are said to have been placed in the hands of each artillery officer. The Correspondent of The Times in the city wrote that it was significant of the amount of confidence that was placed in German promises that, after these pourparlers, it was the general opinion in Antwerp that perhaps the most dangerous spot in the city was likely to be the immediate neighbourhood of the Cathedral.

Up to October 6 the newspapers of Antwerp had continued to endeavour to encourage the people, and even the editions of that evening declared in large type that "La Situation est bonne," and held out hopes of a speedy hurling of the invaders back beyond the river Nethe. On October 7 it was no longer possible to ignore the gravity of the situation. Le Matin that morning declared that it intended to continue publication until the last possible moment, but announced that some of the second line of forts had, on the preceding night, come into action, and that the Administration had arranged for a special service of boats to leave for Ostend at 1 o'clock, on which, as there would be no restaurant facilities, passengers were advised to take their own provisions. "Whatever the future may have in store," wrote the editor of that paper, "all our people have behaved worthily and like heroes. We must now prepare to face the time of trial which we have to go through. Whatever bitterness it may contain, Belgium will emerge from it greater than ever." Similarly La Metropole, in an article " Sous la Menace du Bombardement," acknowledged the critical nature of the situation and, while congratulating the people of Antwerp on their sang-froid, which enabled them to "contemplate with a certain amusement the precipitate departure of a large number of their fellow-citizens," recounted the steps which the people were taking for their personal security, how the majority had stored food, candles and fuel in their cellars, and not a few had banked the openings into the cellars with earth from their gardens or other material. But although there is evident recognition of the gravity of the hour, nowhere does one see any sign of depression. Antwerp awaits events with serenity and in confidence."

These were the last newspapers to be published in Antwerp. The bombardment did not begin at the appointed hour, and throughout the day the city waited in anxious suspense. In the morning the streets were crowded with people hurrying to take passage on the boats which were leaving or to the railway station. Vehicles and porters to carry luggage being equally unobtainable, the spectacle was seen of well-dressed and evidently well-circumstanced men and women dragging trunks along the pavements or bearing portmanteaux on their shoulders. By noon the chief streets were curiously empty. The post offices and most of the public bureaux were closed. The majority of the leading hotels, including those which had been occupied by the members of foreign Legations, Government officials and so forth, had shirt their doors. A great proportion of the shops, restaurants and cafés, especially in the more fashionable parts of the city, were barred and shuttered. There was an almost total absence of vehicular traffic, except as air occasional military or Red Cross motor-car dashed by. In the course of the day the Correspondent of The Times visited the fatuous Zoological Gardens arid found the keepers at work with carbines killing all the dangerous animals, lest the cages should be broken by shells and the beasts escape into the streets. In one great grave lay the bodies of two magnificent lions and two lionesses So everywhere the shadow of its coming doom hung over the city; and all day long there was a constant defiling of Belgian troops along the quays and over the bridge of boats which led to the roads westward.

This withdrawal of the troops, however, was skilfully screened, not only by the fire from the forts in the inner line most directly in the line. of attack and from batteries dispersed behind various kinds of cover at points before the town, but also by the continued holding of some of the advanced trenches well beyond Contich and not far from the river. The troops who held these advanced trenches until the last, suffering heavy casualties and running evident risk of being either annihilated or captured, were both British and Belgian, and they clang to their dangerous work with equal courage. One must presume that the German commander was completely deceived. It is true that the Belgian artillery was, as always, admirably handled, and that the inner line of forts would have made a direct attack in force by infantry very costly. But it is also true that if General von Beseler, after he had made good his footing on the north side of the river at daybreak of October 6, had pressed his advantage at once, he must, whatever his own loss might be, have taken a very much larger number of prisoners from the enemy, besides a great quantity of guns and supplies. As it was, he was content to spend two days in searching the intervening country with his artillery, making no effective attack upon the trenches beyond the constant harassing of them with shrapnel, causing not a few casualties, indeed, but by no means forcing heir evacuation. Perhaps he had difficulty in getting guns across the river. In any event, nearly 48 hours elapsed after the forcing of the crossing of the Nethe before the first shells fell on Antwerp; and with every hour his prize was melting away from his grasp.

It was not until three or four minutes before midnight of October 7 that the. actual bombardment of the city began. It has already been said that the Germans did not bring up their heaviest guns against the city itself. From the first until the end, though high-explosive shells were also employed, the great majority of the projectiles used were shrapnel, which generally burst above the roofs. The actual destruction of the fabric of buildings, therefore, was at no time large in proportion to the severity of the bombardment. The object of the attacking force was evidently to terrorise and to kill, rather than to destroy buildings. And from the first the fire was distributed with curious impartiality all over the city. This had, indeed, been the German plan throughout the approach to the city. So long as the outer torts had presented a definite and stationarv objective, fire had been concentrated on one or another until the big howitzers had battered it to pieces. Thereafter the way in which the Belgian guns and trenches were scattered over a large area made any concentration of fire in the attack difficult. At moments there was evident a definite aiming at a village, a captive balloon, a certain section of the trenches, a railway bridge, or the supposed whereabouts of an armoured train. But for the most part the fire was extraordinarily diffused: a general searching of the country without, apparently, any particular objective, the result being that in proportion to the ammunition expended the casualties were few, except in those trenches immediately confronting the points (first at Waelhem and later near Lierre) where the attempts were made to cross the river.

So it was in the city. A lively controversy afterwards developed as to winch part of Antwerp had the honour of receiving the first shells ; and half a dozen different localities claimed tire distinction with equal confidence. In fact, even the first half-dozen shells which came in rapid succession-were widely scattered, and shells which burst over the roof-to1is seem in the silence of midnight very close to all parts of a wide area.

For many nights before the end Antwerp had been going to bed early. The streets were in darkness after 8 o'clock, and from that hour no restaurant or hotel was permitted to serve food, nor was any light allowed to shine from a window into the street. Beginning with the evening of October 6, the regulations were even more strict. No street lamps were lighted at all, and the tramway service ceased at 6 o'clock. No illumination, visible from without, was permitted after dusk. As the obscurity of night settled down, therefore, Antwerp was as dark as the heart of a forest. There was hardly a vehicle or a footfall in the streets, and indoors the larger proportion of the population withdrew at evening to-if it had not spent the day in its cellars. Few people probably slept in their beds on that night of October 7, and fewer still slept at all after midnight. By far the greater number spent the last hours of darkness while the shells crashed outside, in gathering together such household goods as it was possible to carry away, and with the dawn began that amazing outpouring of the population of the city which will probably live in history as one of the pathetic incidents of all time.

It has been explained why, in spite of the emigration of a considerable proportion of the more affluent classes of the citizens, in spite of the departure of tire British and French residents and the Government officials, and of the commencement of the withdrawal of the troops , Antwerp was stll populous. It had received an immense influx of refugees who came to it for safety and were reluctant to go further. On October 7 there were probably still 400,000 or 500,000 people in the city. By nightfall of October 8 there remained only a few hundred. By far the greater portion of this immense population left the town between daylight and the middle of the afternoon of that day by a single high-road and mostly on foot. Like the population of any other large city, it included people of all walks in life, of both sexes and all ages, and it had the usual proportion of very old and very young, of sick and infirm. Obviously also, the fact that so large a number were refugees who had already fled from other places, coupled with the further fact that all had been under peculiar mental strain for some days and practically all had spent at least one sleepless night, made them in the mass more than ordinarily unfitted to face the hardships of the journey. Nearly all carried burdens, of food or bedding or household effects, to the limit of their strength.

From early morning on October 8 an immense mass of people, estimated at one tune to number over 100,000, crowded the Steen and the Quai Van Dyck, waiting for the ferry-boat to take them across the river to the railway. Close by, over the bridge of boats, pressed an uninterrupted stream of soldiers, military motor-cars, and transport wagons. All along the Quai Jordaens and about the docks people swarmed on to craft over every kind : packets, tugs, cargo boats, later in the day coal barges and lighters, anything that would float was pressed into service for the urgent need of the moment - namely, to get the fugitives away from Antwerp. The destination was immaterial. Flushing. Folkestone, Tilbury, Ostend, Zeebrugge, Lillo, Terneuzen, Rotterdam ; it did not matter as long as the boat would go somewhere away from the Germans.

By these various channels it may he that 150,000 to 200,000 people made their escape but the outstanding episode of the exodus was the pitiable procession which poured out by road by Wilimarsdonck and Eeckeren to the Dutch frontier. Probably not less than a quarter of a million people took that rood.

Moving at a foot's pace went every conceivable kind of vehicle great timber wagons, heaped with household goods topped with mattresses and bedding, drawn by one or two slow-moving stout Flemish horses, many of the wagons having, piled upon the bedding, as many as .30 people of all ages ; carts of lesser degree of every kind from the delivery vans of fashionable shops to farm vehicles and wagons from the docks ; private carriages and hired cabs occasional motor-cars, doomed to the same pace as the faun team; dog-carts drawn by anything train one to four of those plucky Belgian dogs, the prevailing type of which looks almost like pure dingo; hand-trucks, push-carts, wheelbarrows, perambulators, and bicycles ; everything loaded as It had never been loaded before and all alike creeping along in one solid unending mass, converting the long white roads into dark ribands, 20 miles long, of animals and humanity.

Between and around and filling all the gaps among these vehicles went the foot passengers, each also loaded with bundles and burdens of every kind, clothes and household goods, string bags filled with great round loaves of bread and other provisions for the road, children's toys, and whatever possessions were most prized. Men and women, young and old, hale and infirm, lame men limping, blind led by little children, countless women with babies in their arms, many children carrying others not much smaller than themselves; frail and delicate girls staggering under burdens that a strong man might shrink from carrying a mile ; well-dressed women with dressing bags in one hand and a pet dog led with the other; aged men bending double over their crutched sticks.

Mixed up with the vehicles and the people were cattle, black and white Flemish cows, singly or in bunches of three or four tied abreast with ropes, lounging with swinging heads amid the throng. Now and again one saw goats. Innumerable dogs ran in and out of the crowd, trying in bewilderment to keep in touch with their masters. On carts were crates of poultry and chickens, and baskets containing cats. Men, women and children carried cages with parrots, canaries, and other birds; and, peeping out of bundles and string bags - generally carried by the elder members of the families were Teddy bears, golliwogs, and children's rocking-horses. It was impossible not to be touched by the tenderness which made these wretched folk, already overburdened, struggle to take with them their pets and their children's playthings.

From Antwerp to the Dutch frontier, whether at Putte or by Santvliet and Ossendrecht, is about 10 miles. But the actual frontier was only a half-way stage on the journey. There on Thursday and Friday nights there was a huge and pathetic encampment. Some hundreds of tramcars had been ran down to the terminus of the line at the frontier, and gave sleeping quarters to thousands of the refugees but the great majority slept, of course, in the open air.

As a means of conveyance the tramways could not accommodate more than a very small percentage of the crowd, the volume of which poured on almost without diminution over the roads to Bergen-op-Zoom or Roosendaal, whence trains of immense length, loaded to the last inch of standing room, carried the fugitives to Rotterdam, to Flushing, and other places. Only a small proportion of the mass of people, burdened as they were and in the congested condition of the roads, covered the 20 miles from Antwerp to Bergen or Roosendaal in one day. To the vast majority it was a two-days long tramp under most distressing and arduous conditions before the railway was reached.

*(October13, 1914, From the correspondent of The Times, who witnessed the exodus from Antwerp on the morning of October 5, and accompanied the fugitives for a few miles along the road, then rejoined the procession on the afternoon of October and walked with - and as part of it - as far as Bergen-op- Zoom.)

Of course, the dreadful pilgrimage had its individual tragedies. Here were the sick, no matter what their disease or how critical its stage, on wagons, in wheelbarrows and hand-carts, being carried on improvised stretchers or hobbling on their feet as best they could. in such a concourse, also, it was inevitable that there should be mothers who had just been confined, with babies, in some cases, only a day or two days old. Babies also were horn upon the road. There were some deaths by the wayside ; more in the succeeding days as a result of the shock and exposure of the journey. Happily. however, the weather throughout the time was beautiful, with bright autumn sunshine, not too hot, during the days, and crisp, cool nights. Happily, too, the road lay through an almost perfectly flat country.

Here, also, mention should he made of the extreme kindness and hospitality of the Dutch people. It is said that in all over 1,500,000 refugees from Belgium sought safety in Holland in the months of August, September and October. Probably not less than half a million crossed the frontier in the course of the three days from the 7th to the 10th of October, for, besides the stream which poured from Antwerp, minor streams flowed into Holland, wherever there was a road, from all the towns and villages along the north of Belgium and these streams continued to flow until the beginning of November, as the population fled from one place after another in all the country from Antwerp to Ostend. At the time of the fall of Antwerp the chief volume of this incoming tide bore heaviest upon the town of Bergen-op-Zoom With a total population in ordinary times about 16,000, it had suddenly thrown upon in the course of two or three days, over 300 000 people. Every effort was made to get them out by railway as fast as possible to Roosendaal whence they could be distributed to other parts of Holland. But it was not possible to pass them out as fast as they came in, and for several days Bergen fed and cared for a refugee population of upwards of 100,000. The problem of feeding them was a very serious one. Five or six days passed before supplies in sufficient quantities could be brought in from other towns - which were also feeling the strain upon their stores - and during those days the regular residents of Bergen suffered no little privation. A month afterwards 20 000 Belgians, more than doubling the population of the town, remained either distributed among the private houses or quartered in two large camps, being supported at the public expense. But though, perhaps, the burden fell more heavily on Bergen-op-Zoom than on any other town, nothing could exceed the universal kindliness and ungrudging generosity with which the "vluchtelingen" were treated throughout Holland, by the Government and by all classes of the people.

As soon as the fugitives had fairly left the city of Antwerp behind they were beyond the reach of the German guns; but it was curious that no shells fell at any time among the crowds as they were struggling through the streets.

Shells reached the quays and fell in the river - one narrowly missing a crowded Ostend boat as it put out - and wrecked, later in the day, some of the structures by the riverside, but nowhere, during those perilous hours, did one fall anywhere among the massed people. Towards noon, as the procession struggled along the road to Holland, a German aeroplane circled overhead, apparently studying what was going on below, and was fired upon by guns from the forts on the west side of the Scheldt. All day long- also on the west of the Scheldt - there rose into the air, steadily increasing in volume, the great triple column of black smoke from the burning oil tanks.

The bombardment, which had begun at midnight on October 7, continued with varying severity throughout the 8th. As the Germans drew nearer to the city all the inner forts on the south and east sides of the ring took part in replying to their cannonade. Some of these forts - notably Forts 2, 3, 4 and 5 - were badly battered, but with the guns posted between and before them. continued to answer vigorously the enemy's fire, while trenches two miles in advance were still held by both British and Belgian troops. The Germans made no attempt to rush these trenches or the zone of barbed wire entanglements which would have to be crossed to reach the city; but contented themselves with pouring shell fire upon the trenches, the forts, and the city itself from beyond the reach of rifles.

Shelling the city, however, after noon of October 8 could do little good; for Antwerp was no longer a city but only the husk of one. All the streets, usually so busy and so gay, were shuttered, silent and deserted. By the shells as they continued to fall-now chipping the corner off a building, now crashing through a wall or falling harmlessly in an empty square or garden - there was hardly a human being to be either hurt or frightened. Devoted Nurses and doctors there were struggling to get their wounded patients to places of safety. *

*(Three British hospitals in Antwerp continued to operate until noon of October 5 and all succeeded in getting their patients away, namely, the English colony Hospital, under Nurse Edith Ware, the British Field Hospital, and Mrs. St. Clair Strobart's British Women's Hospital.)

Craft of various kinds was still passing out of the dock basins into the Scheldt, and in the immediate vicinity of the wharves a few cabarets kept open. Two or three hotels, in safer positions in the city, with much-reduced staffs, also did not close up. With these exceptions, the nurses and their wounded, the military, some city officials, half a dozen British newspaper correspondents, and a certain number of dubious citizens who had good reason to know that they had nothing to fear from falling into German hands, represented practically the whole population of Antwerp. In the shuttered and desolate streets not a vehicle moved. Now and again a solitary figure hurried along, stopping to shelter in a doorway as a shell screamed overhead. Otherwise Antwerp, which yesterday had held half a million people, was like a city of the dead.

As dusk fell a detail of Belgian soldiers sink by rifle fire a number of lighters in the channel from the outer to the inner dock basin, so closing the last exit by water; and then followed a sight which offered, to those few who witnessed it, what was perhaps one of the most terrible spectacles that the world has seen.

Across the river still rose into the sky the great triple pillar of smoke from the burning oil tanks. The air was windless and the thick vapor rose straight upwards for some hundreds of feet. There it apparently encountered a light breeze, for, very slowly, still black and solid as a pall, it drifted steadily beet almost imperceptibly north-eastwards. spreading out till it covered half the sky. By nightfall this heavy curtain overlay the greater part of the city and stretched away into the distance. In the darkness the blaze of the burning oil became visible, tossing into the air and throwing off great masses of flame to float away like individual clouds of fire. The red glow from below lighted up the whole underside of the black canopy, making such a scene as a man might dream of in visions of the Inferno.

Resting almost stationary overhead, so slow was its drift to east and north, this cloud left below it to the south-cast a strip of clear starlit sky, ringing one-third of the horizon. Against this, looking from the quays or the river, the outline of Antwerp was silhouetted the stately spire of the cathedral, the noble tower of St. Jacque, the dome of the Central Station, and other conspictious buildings being clearly distinguishable above the dark mass of the body of the town. Then, as the night wore on, out of this mass rose other fires - one, two, three, six, ten, fifteen - making almost a continuous ring round the southern and eastern sides of the city. Some of these fires were burning dwelling-houses which had been set on fire by shells; others bad been caused on purpose by the Allies, who were destroying whatever stores might be of comfort to the enemy.

All these - the flames of the burning oil and of all the lesser fires - threw their glow upwards on the pall overhead, caught the points of all the buildings in the city with flame, and were again reflected in the water of the Scheldt, until, above and below, heaven acid earth and water were all blood-red the inside of a hideous furnace, the lid of which was the terrible black cloud of smoke. And inside that furnace, adding immeasurably to the horror, the guns roared, the shells bursting in little lightning flashes of quick spurts of white flame against the black and red.

Intermittent and desultory - perhaps not more than one shot to the second - for the earlier part of the night, about half-past ten the cannonade became truly terrific, by far the heaviest that lead occurred at any stage of the siege. In the continuous and deafening uproar it was no longer possible to distinguish the screaming of the shrapnel, the bursting of the high-explosive shells or the hurtling of the projectiles from the long naval guns, but all blended into one great roll of thunder. It was Chaos come again. Antwerp was in its last agony; and never surely did great city have a more terrific passing.

Before the first grey of dawn the clamour subsided. Cannonading went on in desultory fashion. But the morning had a terror of its own, for the black pall still shrouded the sky. No longer illumined with the flames - for the oil had burned itself out-it hung a leaden shield between the sun and half the city and all the country to the north, so that the day could not break, but until an hour or two of noon twilight prevailed. It truly seemed as if the day itself mourned for fallen Antwerp.